Final report for FNC20-1254

Project Information

We are a 1,200-acre certified organic farm. We grow grains, native fruit, soybeans and blue corn. We have a long crop rotation and are starting to use more cover crops. We are sustainable, but are beginning to expand into fewer inputs and using green manures. In the past couple of years, we have been certified by the Minnesota Agricultural Water Quality Certification Program.

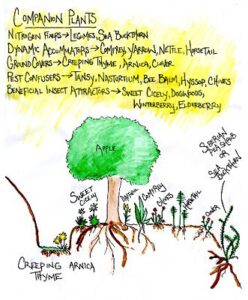

An example of planting around a fruit tree. We used this model

An example of planting around a fruit tree. We used this model

as well as mint plants and basil.

This is an idea we used for planting around fruit trees.

The French and Germans believe in working with nature and the natural deterrents. Many plants repel insects that can cause disease in fruit trees and shrubs, so by planting together this insect-repellent vegetation, you have better potential for reducing disease. The method we used is to start incorporating more insect-repelling plants, which I never thought about using before. An immigrant farmer on our farm is helping me to develop this farming method.

Adjuncts (added to the beer mash) are used in craft beer to enhance flavor, mouth feel, aroma and clarity. Adjuncts have virtually endless uses and can be locally grown such as grain that can be flaked or malted, rhubarb, apples or herbs. The 500+ breweries in Minnesota require a variety of options for adjuncts. With this grant, we will identify which adjuncts are in local demand and move forward to create a collaboration of learning and base connections between breweries and local farmers. Most breweries lack business relationships with the area farmers and order from big malting houses, which takes a huge cut of the profits with the farmers receiving less share. An adjunct added to one singular batch of beer (breweries can have 12 batches brewing) might require 400 pounds of fruit or malted grains. For small farms and diverse farmers, it is a great economic opportunity to sell to a brewery. This grant helps add value to farm products, creates more connections to the land and environment (such as fruit trees and shrubs providing more pollinator habitats, or grains such as oats providing better crop rotation), along with a stronger rural economy.

"Before this grant I never really thought about selling my fruit to a brewery. It has always been a problem when everything is ripening fast and you have to find market share. I think going forward it will fit perfectly to pick everything and drop off at a brewery. It was such beautiful fruit last year before this grant and most of it ripened quickly and I had no market share so the fruit went to waste," said Michele Trangsrud, a North Dakota farmer.

Identify quantity and quality of grains and fruits to provide in a beer mash followed by documentation of these varieties. The grains for hard red spring wheat that work particularly well are Linkert, Glenn, and Washburn. For flaking, the moisture content of the wheat needs to be above 12%, but this can cause issues for the farmer when it comes to long-term storage of the grain. Usually, a farmer would want 13% moisture of grain, at the highest, for storage in the grain bin, because it can mold especially at high temperatures in summer. However, if the moisture is too low for flaking (under 11%) the wheat would shatter and crush into mush during flaking or look like flour, thus creating a mess for the brewery. Heat, air and moisture are the enemies of whole grains, so a moisture-tester for on-farm use is an absolute must for flaking any wheat to be used as an adjunct.

Provide a stable method of keeping the grains and fruits (freezing, drying or juicing). The fruits need a strong coordination of delivery between farmer and brewery. Mid-sized craft breweries need over 300 pounds at one time. So for picking, cleaning and transportation, there has to be clear communication of time frames, delivery and coordinated processes. We found using fresh was the best, but only if cooling of the fruit, picking and transportation could be done early in the morning. Also, storing fruit in coolers in air conditioned cars was also very important. Most of the more creative artisan breweries prefer fresh fruit while others prefer the fruit to be heated and packaged into a slurry (much like pie filling) for longer storage. Fifty percent of all breweries work with companies from Oregon, which makes fruit from the West Coast our biggest competition. The Oregon fruit comes in foil pouches, which are added directly to the mash toward the end of brewing. One way to make headway in adding local fruits to beer-making is to be able to offer flavors and varieties that are not available from West Coast suppliers. Once the fruit is ripe, there is a short window for the fruit to be picked, cleaned and stored – all during the hottest months of the summer – but it may not fit into the brewers' schedule. Fruit can quickly rot, a storm can knock fruit off the tree or shrub, or birds can quickly eat all of the production.

Marketing of local fruit almost has to take a year in advance, due to the trial and error required on the brewer's part of finding the perfect flavor combination between strong-flavored fruits and bitter hops. Due to the challenges of finding that perfect flavor and marketing setbacks, it is imperative to provide samples a year in advance for experimental purposes to the brewer.

Communicating your quality and quantity projection is another critical aspect to ensure success. Dried fruit is not preferred for fresh local fruits as it adds extra steps of rehydrating. It may be something brewers in the future request, but currently the greatest appeal of local fruit is presenting an opportunity for the brewer to see and smell the the fresh product, get creative as they think of fun ways to incorporate it and be able to market to customers that a local farmer was involved in the process. These positive and emotional experiences all add to the "craft."

Evaluate the taste and consumer acceptance of what sells and what each brewery prefers. This aspect was much more dependent on the subjective palate of the breweries' head brewers. While some may like tart cherries, others may not want that flavor at all. Lead tasters in breweries are very exact and any change of staff also means a change in preference. From everything we have researched, we have found that the fruitier and sweeter flavors are currently preferred by most consumers as opposed to the classic bitterness of grandpa beers. As Corey, head brewer at Junkyard, says: “In the past few years we have seen more buying of fruity, even sour beers with fruit in it. The young generation that is in their mid-20s prefers flavors I would not even of imagined or brewed in my 20s. We have adjusted that quickly and it seems to change going forward.” Another variable that native fruits can add to the brew is color. Once fruit beers are brewed, they exhibit the color of their added fruit, especially in light-colored wheat beers. Fruit can also add a pleasing reddish cast to darker beers, such as stouts and porters. Few fruit beers fall in between these color extremes. Varying health benefits of adding fruit components are just being discovered too, which tends to take away some guilt of having an alcoholic beverage.

The optimal parameters for fruit creates HUGE amount of work yet to do. Some wanted juice, some wanted to juice the fruit themselves. Some use fruit just to strain beer through it while some brew with it. For digging deeper, we texted an assortment of brewers and asked questions, such as:

What fruits would you use if locally sourced?

What quantities would you need for even a test batch?

For organic fruits, the most often stated preferences were for:

- Cherries

- Peaches

- Apricots

- Strawberries

- Blueberries

Share info with other producers and breweries. Because the shrubs and trees do not bear fruit until they have matured, it takes coordination of many farmers together for risk management. One field may bear a lot one year and the other nothing at all. Spring pollination and temperatures dictate what will be available. Best practice is to involve multiple farms and support coordination between those farmers to allow for drop-off and pick-up times for crops. Honeyberries, tart cherries, aronia berries, and apples, for example, show promise for beer making. The best method we found is to enlist friends and family to pick two pounds. They keep one pound and the other pound goes to the farmer. Given the opportunity, getting pre-orders from the brewery is yet another option. Another idea would be a fun "will pick for free beer" promotion: In exchange for picking the berries, the pickers would be able to trade their harvest for gift certificates to the brewery, thus providing a sense of ownership and participation in the process. This would be an especially fun activity during times of COVID-19 because it gives an excuse to be outdoors and enjoy nature all while getting a discount off of a normally expensive alcoholic beverage.

If possible, purchase shrubs and trees locally from your county offices. Shrubs and trees can be expensive, so we bought from Clay County Water and Soil Conservation Office. Every county has an office like this, usually located by the USDA Farm Service Agency. The Conservation office also can be invaluable in helping you determine how the soil in your area matches up with the variety and species of fruit you would like to purchase. In Minnesota alone, soils can shift from heavy, packed clay to sandy soil within a 20-mile drive. (Blackcap raspberries, for instance, do well in clay soils, but not so with other raspberry varieties.) You can also request fruit trees such as pears to purchase from the Water and Soil Conservation Agency, but you usually have to buy a complete bundle of them (30 trees). Then again, at the extremely affordable $2 to $3 per bareroot, it is worth it to order a bundle!

Evaluate the sizes of grains and fruit used by the breweries (thickness or thinness of grain flakes, size of fruit pieces, or whether they prefer to use a slurry).

Meticulously test and track data, setting standards for moisture, protein and fungus. Pay close attention to the Brix scale to measure fruit sugars. The most convenient way to provide for a brewery is to have them give you the exact detail of flake size and you treat this information like it is another ingredient. If there is no fungus and no marks, that means you have a prime fruit. Brewmasters and staff are savvy with taste. There was a time when I switched wheat varieties to see if they could tell the difference and within 10 minutes of dropping off I received a phone call asking why it tasted a bit different.

Evaluate pollinator habitat created. The pollinator habitat is planted and has emerged. For obvious reasons, it is beneficial to have this habitat in tree areas. Farmers can also invite other beekeepers, like we do, to maintain the habitat for the bees. We've found hosting honeybees also keeps native bees working a little harder to compete with the honeybees. This is a win-win. The best pollinator seed is one that you can source regionally to make sure the planted seeds grow, can handle harsh winters and are the right choice for the growing zone. I found pollinator seeds at Agassiz Seed in West Fargo, N.D., and was able to buy in bulk (cp-42 about 28$ a pound.) If using NRCS programs such as EQUIP for developing pollinator habitat make sure that mixture is approved by NRCS before buying.

Cooperators

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

Research

| Visiting breweries and taste-testing of the grains from seed houses before planting. | Due to COVID-19 we did not tour as many breweries. It was important to document results and provide a chart of best flavors for the adjuncts. It is best to have flake size determined by breweries and to then follow their lead with what they want. Something to note is that the malting process has the ability to change the flavor of some of the grains by adding a sweeter flavor. Every batch has to be tested in a lab in New York for the specific test results that breweries require. Even if you have the right grain, the malting process can go wrong, rendering the product less valuable. Minimum amount can be a 2,000-pound to 4,000-pound batch, which is a lot to market. The current pandemic has made the market extremely unpredictable, which, in turn, makes this project very much a trial-and-error method. The risk involved caused some setback in the process, where the farmer usually holds the most risk. It is best to have a pool of farmers you can trust and work with. It is unknown what impacts COVID-19 will have going forward so we are not sure of what the demand will be for local breweries. City, state and county mandates (for closing, etc.) will, in part, determine the outcomes. | |

| Gather a community list of adjuncts that could be available to brewers | There may be other farms with adjuncts available for breweries, so by finding different adjunct options that are successfully grown in Minnesota, this helps inform our offerings. We texted brewers and also asked them to respond for our survey. An example of a text messages to brewers were:

What fruits would you use if locally sourced? What quantities would you need for even a test batch? Results of the survey indicated that brewers would like to work with raspberries, honeyberries, chokecherries, apples, and tart cherries, while grapes usually used for wines (but now used in beers) show promise too. Wheat and rye flakes are of lesser demand compared to malted barley, which is traditionally the most common grain used in beer. Demand for stouts and heavier beers is higher in winter months, which requires more grain. Farmers should consider holding inventory until a brew schedule is rolled out (planned months in advance). This being said, it is important to band together with other farmers as brewers may require, at minimum, a batch of 300 pounds of fruit or more. We are still experimenting with these added grains ourselves. We found a few niches for flaked sorghum to use in food to add sweetness. Because of the customer demand, farms must have the ability to get the fruit and grains out in a short time to turn around to the brewery. Farmers would have to be prepared to drop everything happening on the farm to meet demand. |

|

| Create online survey for brewers on what adjuncts we could provide and their top choices and amount of fruits needed. |

|

|

| Determine fields/areas for best growing conditions | Some fields will provide better growth rates for certain grains and additional fruits than others. By growing between the three farms we can ensure optimal conditions for planting. The soils vary from clay to sandy loam, so it was essential to find areas where the shrubs and trees can withstand wind, snow, and any rodent/deer pressure. Electric fencing and netting are critical. Within a few days without fencing, animals would eat the fruit – especially varieties like tart cherries or honeyberries. An important aspect to the pollinator communities is preventing spray drift in open areas because the pollinators can be wiped out if this occurs. The fruit itself is another area that requires close attention. One day the fruit can be too green while the next, after temperatures spike, the fruit can be nearly spoiled. This usually comes in the hotter months such as August when farmers' workload is already preoccupied with grain harvest. When planning for spring, make sure to look at offerings of bare-root trees and shrubs from your local county water and soil conservation office as they are generally as affordable as $1.50 to $2 for a bareroot tree or shrub. The list of trees and shrubs available through the county nursery program is usually available mid-October for following spring pick-up and planting. This makes it an economically appealing source for trees. Something to note is that in the midst of COVID-19, most nursery programs were selling out of elderberry (because of anti-viral properties of the fruit). Regardless of where you buy from, make sure the plants/bare roots can tolerate your growing zone. Big ox stores or chains may offer some fruit- bearing trees, but they may not be right for your growing zone. | |

| Research large malting houses currently providing to breweries | Finding their price points and flavorings will help determine competitive pricing for the farmers, as well as any market trends. The largest malting house in North America is in Shakopee, Minn. This is a huge supplier which makes orders as easy as pushing a button. We have just recently offered online ordering so we can offer our malting/grains to consumers at www.doubtingthomasfarms.com. We began this right at the time that the pandemic hit, where we found ourselves in a new "normal" and became busy just troubleshooting. | |

| Documentation of growing conditions, fertilizing, weed control. | Look at the overall picture for farmers and the extra workload to determine if selling to breweries could be a viable option for them. The best method for weed control is till mowing/weeding. Growing conditions are to plant bare-root and lightly fertilize in spring before a rain event. We found that planting a combination of herbs and flowers around trees provided less insect damage to the fruit. Using the French and German methods of growing was also helpful. We had a native speaker/reader who could translate the German and French literature for us and we had great success in using these different methods. Grazing of the tree area and using overripe fruit for animals was good to keep the tree area clean as well. | |

| Measurements and documentation of fruit and grain size, protein, moisture, fungus, flaked, malted, and Brix content. |

Create a dialogue between brewers and farmers with what is needed to create the next craft beer. Create a standard for high-quality product being sold to brewers by looking at data collected, brewer reference and how it performed in the brew. This information is heavily dependent on the brewery. Flake size is usually preferred thicker rather than thin – much like a thick rolled oat. Zero fungus and less protein in the wheat (less than 14) are essential, otherwise it can cause problems. Caution must be made to not use feed-value grains, or fungus disease can multiply in the malting process. |

|

| Field day event | Share findings, provide Q&A for prospective farmer/brewer relationships, and share final products with consumers. It's all about creating buzz for more farm-to-glass relationship building. The event was held at MOSES February 2020 in LaCrosse with a poster presentation as well as round table. Samples were shared with participants, farmers, researchers, and research students. |

We developed a line of 100%-certified organic malted barley and sprouted wheat (for flour). This will roll out after the final inspection, (with COVID-19, organic inspectors were not traveling much). The application for organic malted grains is complete and submitted to GOA, a USDA third-party inspection and certifying agency. After final inspection, Vertical Malt in Crookston plans to offer a line of locally grown certified organic malt by next summer. A side note, women-owned breweries are interested in working with other women in this grant in order to create varieties that have been exclusively grown, malted and sold to them by women. I did not anticipate seeing this type of partnership develop, but plan on continuing to explore more.

We had a good growing year for chokecherries, raspberries and cherries. However, the cherries turned from almost ripe to wormy in a short period. Because of this, we've learned they must be picked right before peak. We developed standard operating procedure for using native fruits. The native fruits did well. We will have to increase future production and will include other farmers/landowners as a cooperative model going forward. It will take several farms to even supply one mid-sized brewery. It takes attention to detail as well as extremely strong communication skills. Any snafus in the process can corrupt working relationships with brewers. We developed a guide (attached) for use of native fruits. Concern of cyanide in the pits of two popular local fruits, chokecherries and elderberries, put an immediate stop to their use. We realized there was information missing about the cyanide in native berry pits and safety issues. The brewers were scared to use once they saw cyanide so the brewers put on hold till this winter to use the now frozen berries. We reached out to many professionals to help provide guidance. Hence, a good guide was developed to help inform future crops. We also found homebrewers were fond of raspberries and strawberries too.

We developed contacts for use of organic and heritage grains (not developed before). This is also done in collaboration with a new group formed right at the right time! https://mndaily.com/263329/news/going-against-the-grain-umn-establishing-tool-to-connect-organic-farmers-to-brewers/

We learned barley, such as Conlon, can be saved and replanted, which is different compared to conventional barley seed. The partnership on this grant with NDSU opened the door for more research on barley varieties that yield well, grow well and taste great, but are also critical in providing a market share for food such as pearled barley for soups and stews. So, in essence, we are seeking development of a double-duty barley. Dr. Horsely of Plant Sciences at NDSU and our farm will work together more on this and do additional work to enhance flavor, disease resistance and yield. Since some of the older varieties of barley yield far less, this could be a great avenue to explore. It is critical that barley be at least 65% plump for specifications, otherwise it does not pearl or malt well at all. This is a gold standard; if there are any misses, such as a wet year, the farmer will only receive 1/3 of the revenue from the field. Malted grains are also being developed for culinary use. This is a slow-moving development, but the flavor has been used by five chefs, four of whom are James Beard Award winners. The malted grains can be used much like rice by chefs and have great potential as a versatile food or pantry staple. The rye and wheat flakes also have applications for artisan chefs looking to create a hearty porridge. As a cover crop, rye shows promise too in food as well as flours. At this time the hybrid rye was not favored for flavor preference.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation Summary:

The main event was held at a research forum at Midwest Organic & Sustainable Education Service (MOSES). We were chosen to present at this research forum, along with a three-day event, to explain our findings. Our presentation generated so much interest that we were all kept busy answering questions, presenting data and following up. We displayed a poster with a QR code for follow-up as well.

Every batch of malt has to be tested in a lab for results of how it will brew. The tests are $100 each and there are a bunch of labs doing this. The brewer will ask about your testing and results. Have the test ready to go! Do NOT market without this!

NoreenThomas Malt test results reflects a test done on the barley after malting. There are not any guidelines for malting other grains such as oats.

Learning Outcomes

I would tell farmers that they must have the right grade barley, have access to cleaning equipment, and must then be able to malt the grains or have access to a malting place. Growing barley alone is not enough; you need this whole loop process in place for it to work. It is rewarding work but a lot of work. If selling fruits, this can be a one-stop place to market your fruit, if you have enough quantity. I think being within a 4- to 6-hour drive to the brewery is critical; otherwise freezing and drying fruits are an option.

In my 17 years of selling local food and products, I found breweries to be the most relationship focused of any other type of local food or fruit market. The brewery staff are fun and creative – much like artists – and keenly sensitive to any subtleties or changes in flavor. Older women farmers can be in the mix of young men and women who work in the breweries. As relationships are paramount, I've learned to stay in front of them or they they can easily forget you. It is plain marketing on a bigger level. There is a lot of work to do yet, but without this grant we would not have started. The growth and learning curves are straight up and continue to be so!

It is much easier as a producer to market at one-stop place like a brewery. It is a one-stop interaction and transaction, vs. a farmer's market that requires standing all day in the hot sun and still selling less fruit than you could in a single trip to a brewery.

Project Outcomes

A beginning Minnesota farmer was quick to add, "As a beginning farmer, I was able to grow barley and make quality grade for malting. It was exciting as the crops were harvested." This meant more cashflow for the farmer.

Through the Grain Alliance collaboration, women brewers reached out and are interested in buying from women farmers. As this "FarmHer" releases the malt barley in early 2021, she is finding a new avenue for her barley as well as connections she did not have before. This would not of happened without this grant nor without the ability to reach out.

We also developed an online store for reaching home beer brewers.

We are adding several other farmers to our online store while featuring their farm story. We will be applying for a grant to do more cooperative selling/farming/online together. SPROUT, a food hub in Little Falls, Minn., will also have all of us as an online "beta" for selling through them. They are all beginning farmers who I am coaching to help launch on their own. The online store can be found at: www.doubtingthomasfarms.com.

This was so timely! Right now the University of Minnesota (UMN) is rolling out an Organic Grain Alliance. All this knowledge will be shared with a large group of people as well as its sister group, the Artisan Grain Collaborative, which is a nonprofit we joined to help create further awareness.