Final report for FNE19-930

Project Information

This research project collected forage data for six common woody tree species (Poplar, Willow, Black Locust, Buckthorn, Honeysuckle, and Wild Cherry) at Wellspring Forest Farm in the Finger Lakes region of New York. The data allowed us to assess baseline nutrition of each species and how values changed over the season. We collected data over two seasons in 2019 and 2020, which offered sample data in both an exceptionally dry and excessively wet season to compare.

Results indicate that all species provide excellent feed value, with the exception of Wild Cherry which offers moderate value. Very few feed value or nutrient indicators from the forage tests offered any clear trends to assist in timing of feeding or provide any compelling reason that timing would matter to provide useful nutrition to grazing animals.

As part of this project we also completed a literature review and summary article of tree fodder use and considerations for management and published these resources to make them easily available at www.SilvopastureBook.com. At the conclusion of our research we convened an online Tree Fodder seminar to offer a range of critical perspectives from practitioners and researchers. Overall this project increased the awareness of tree fodder as a valuable contributor to a more productive and resilient grazing system.

This project developed a management guide for utilizing tree fodders with two main components; (1) results of multi-year farm research collecting forage analysis for six species of common woody plants and trees persistent in northeast farm landscape, and (2) a literature review of tree fodder and provide resources for learning on our website to other farmers interested in the topic.

Research established baseline nutritive quality values for the tree/shrub species, accounting for seasonal variation and site characteristics. In addition to the qualitative analysis to assess the food value in various woody plants, our experience and observations offered insight around how to integrate tree fodder into a grazing system. The research and literature review results was shared via a public virtual seminar on December 10, 2021, with recordings and associated materials freely available at our website.

The project results offer farmers the opportunity to improve on-farm productivity and reduce feed costs, which can contribute to an increase in farm income from grazing operations while also increasing grazing resilience in extreme climate conditions. Fodder utilization also offers opportunities to utilize woody plants in resource conservation efforts compatible with rotational grazing, from riparian buffers to windbreaks to nutrient runoff capture.

Woody trees and shrubs offer farmers better utilization of farmland, high-quality feed sources during drought and excessive rain conditions, and the development of silvopasture systems that are among the best farming systems at increasing carbon storage in soil and woody plant material. While there is a long history utilizing woody plant fodders in Europe, South America, New Zealand, Japan, and other global regions, very few farmers are familiar with approaches to successful management in the Northeast.

Many farms have lands covered in both native and non-native shrubs, including species such as willow, poplar, black locust, honeysuckle, buckthorn, privet, autumn olive, and others. These species offer resiliency in extreme conditions when compared to traditional pasture grasses and forbs. Literature suggests that some of these species also have substantial food value, which offer implications for several management approaches at the farm scale.

Since the practice of using such plants as animal fodder is novel in the US, we started with pulling relevant data on nutrition from a range of research literature from around the world. At best, this data suggests the species worth focusing our attention on. The problem lies in that available data is neither from the Northeast US region, nor does it specifically compare relevant species closely over several seasons or offer details about the changes in nutrition within the growing cycle. Trees and shrubs collect sunlight and materials from the soil, and depending on the time of year, more or less

of the compounds are available in the leafy material.

If farmers know that plants have food value to their animals, they will seek more opportunities to include them in grazing plans, knowing better what woody plants to feed their animals. If we know the changes in nutrition over time, farmers can better know when to feed these materials to livestock. While simple forage analysis techniques can offer this data, the ability to consistently sample is cost-prohibitive on a farm-by-farm basis. This funding allowed us to sample extensively (20 samples over two seasons) to develop a more comprehensive picture of tree fodder in the region.

Wellspring Forest Farm is a 50-acre agroforestry inspired farm in the Finger Lakes region of New York. The farm is co-owned and stewarded by Elizabeth, Steve, and Aydin Gabriel and we’ve been in commercial production since 2011 including gourmet mushrooms, maple syrup, duck eggs, pastured lamb, and elderberry extract. We also have a yurt and cabin onsite that we rent as part of an agritourism venture. Our farm is as much an example of production as it is an educational site for people to learn. We offer courses onsite and online, publish articles, and host webinars to teach others about agroforestry and the potential benefits to farms and homesteads. We currently farm part time, with part time seasonal employees.

Cooperators

- (Researcher)

- - Technical Advisor

Research

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

What are base nutritive values for selected Tree Fodder species?

For two seasons, we collected leaf samples to establish a baseline read on the nutrition in the fodder of six selected species, three we had planted extensively (Willow, Poplar, Black Locust) and three found naturalized (Buckthorn, Honeysuckle, Wild Cherry). While the original proposal had planned to compare grazed vs. ungrazed specimens in the second year, the sheer volume of leaf material needed for samples to the lab did not permit this. Instead, we determined it was worthwhile to collect a second year of nutritional data and look for any differences given the seasonal changes (2019 was a wetter year, while 2020 was abnormally dry for most of the season)

Are there trends of change for various nutrition measures over the growing season?

Collecting multiple samples over the course of the grazing season allowed us to examine any significant trends in nutrition values, which would suggest potential times of the year where feeding fodder would be more valuable.

FORAGE SAMPLING PROCEDURE:

A. Complete baseline assessment: We recorded the location of specimens for the 6 species on google earth (See figure 3) using a handheld GPS unit

B. Starting in June when trees are leafed out, each sample was be collected every 2 - 3 weeks, filling a gallon zip lock bag with material. The trees will be randomly sampled and the leaf material mixed together to develop a representative sample vs sampling specific trees repeatedly (not possible due to the amount of material needed). Samples stopped when lead drop began in October.

Species Sampled:

Black Locust (Robinia pseudoacacia)

European Buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica)

Honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica)

Poplar (Populus tremuloides)

Wild Cherry (Prunus avium)

Willow (Salix purprea)

C. Samples were dropped off at DairyOne Labs in Ithaca, NY for forage analysis, including: % Dry Matter, % CrudeProtein, Acid Detergent Fiber, Lignin, Starch, DM, CP, SP, ADF, aNDF, TDN, and Macro and Micro nutrients. Results was entered into a spreadsheet.

During the 2019 season, we successfully collected 8 samples of the 6 species, for a total of 48 sample data sets from 6/24, 7/11, 8/2, 8/19, 9/4, 9/23, 10/4, and 10/25. We waited until late June for the first sample because we wanted to have all species leafed out, but realized in our evaluation of the first year retrospect that samples should have started sooner since may species leaf out far earlier (black locust is very late).

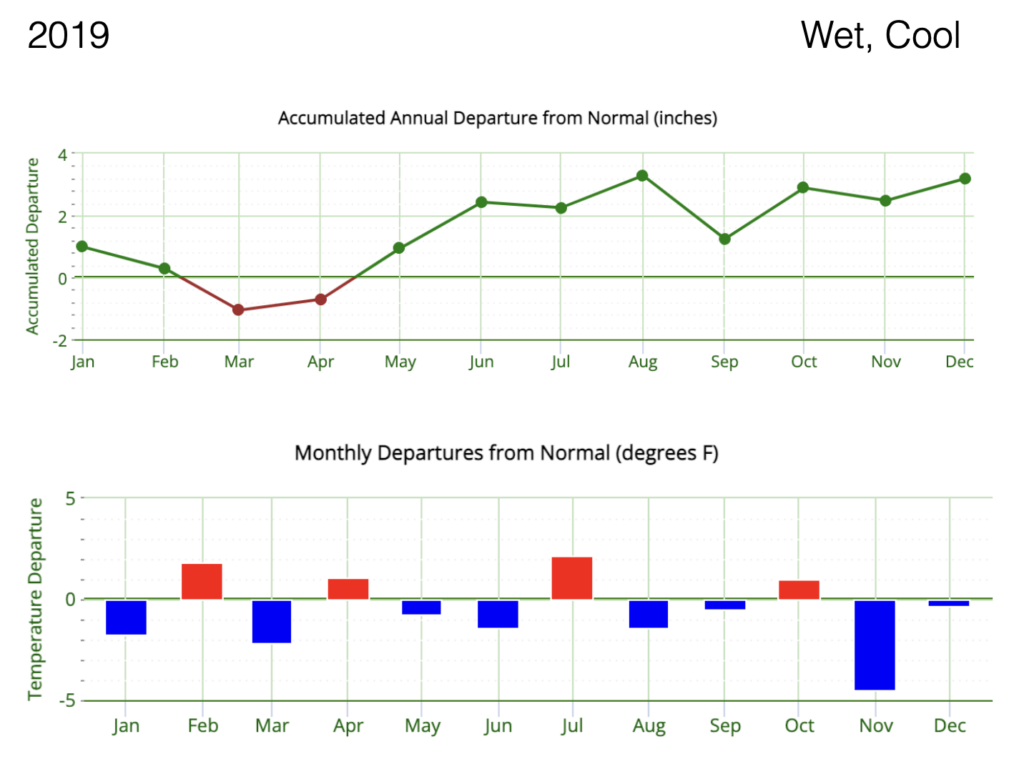

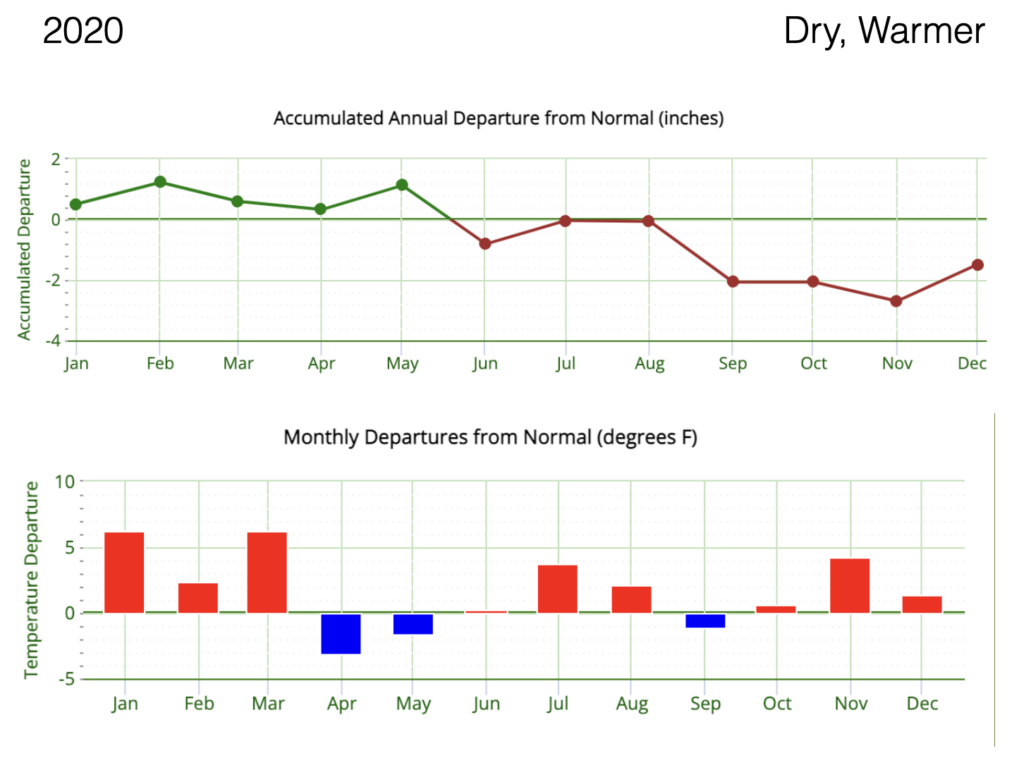

We began baseline sampling in 2020 at an earlier date in June to account for this and decided to stick to a biweekly schedule to gather more accurate data for the second year. In 2020, we documented 12 samples of the 6 species, for a total of 72 sample data sets from 6/4, 6/15, 6/24, 7/6, 7/16, 7/27, 8/6 8/17, 8/27, 9/7, 9/17, and 10/5. The 2019 season was abnormally wet (Figure 1) and the 2020 season was abnormally dry for much of the sample timeframe (Figure 2).

D. Samples were analyzed for totals and averages in Google Sheets. Trends were graphed and R-value calculated to assess the correlation with data sets to a given up or down trend over the course of the season. See below for results of the analysis.

Figure 3 shows the location of sample sites, which were shifted to be closer to the barn and central part of the farm, since multiple people were doing sample collecting. Because of the volume of leaves needed per sample per species, it was not feasible to keep samples separate per tree or continue to harvest from the same few trees each time as we had originally proposed. By combining samples from multiple plants we also got a representative sample of the quality of leaf fodder in the landscape which more accurately reflects the browse experience were the sheep to harvest it. We collected a random sampling from a block of trees and mixed the sample to get a broad representation of the leaf forage available in the landscape for grazing animals. Sampling included plucking leaves, stuffing them into zip lock bags, labeling, and then storing in the fridge until they could be dropped at the lab.

Figure 3: Sampling locations at Wellspring Forest Farm

Average Values: Core Nutrition Metrics

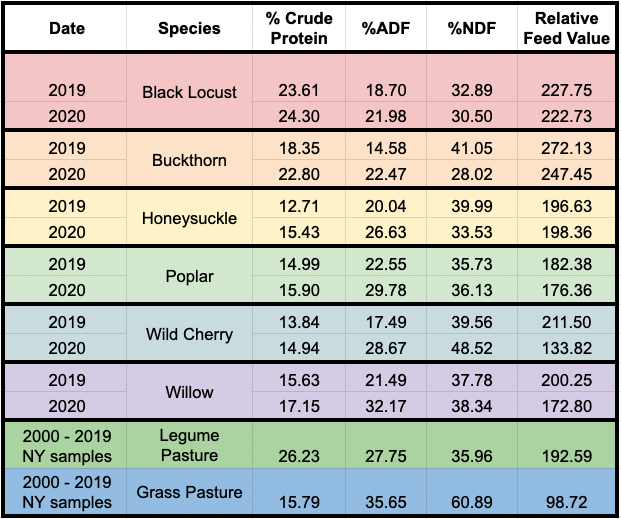

Table 1 below shows the average values for each species over the season during 2019 and 2020. Also included are aggregated datasets from the DairyOne database with pasture forage values based on hundreds of samples for New York state at the bottom of the table, for comparison purposes:

The table highlights the excellent feed quality of these tree fodders, overall. All the tree fodders sampled offer solid CP, ADF, and NDF values, in keeping with guidelines for various life stages of grazing ruminants. (Table 2).

|

NDF |

CP |

|

|

General |

under 70% |

more than 8% |

|

Reproduction |

under 50% |

10 - 12% |

|

Growth |

30 - 40 % |

16 - 18% |

|

Lactation |

under 55% |

12 - 14% |

Table 2: Recommended NDF and CP values for various ruminant life stages.

Source: Ball, D.M., M. Collins, G.D. Lacefield, N.P. Martin, D.A. Mertens, K.E. Olson, D.H. Putnam,D.J. Undersander, and M.W. Wolf. 2001. Understanding Forage Quality.American Farm Bureau Federation Publication 1-01, Park Ridge, IL

Average Values: Macro and Micro Nutrients

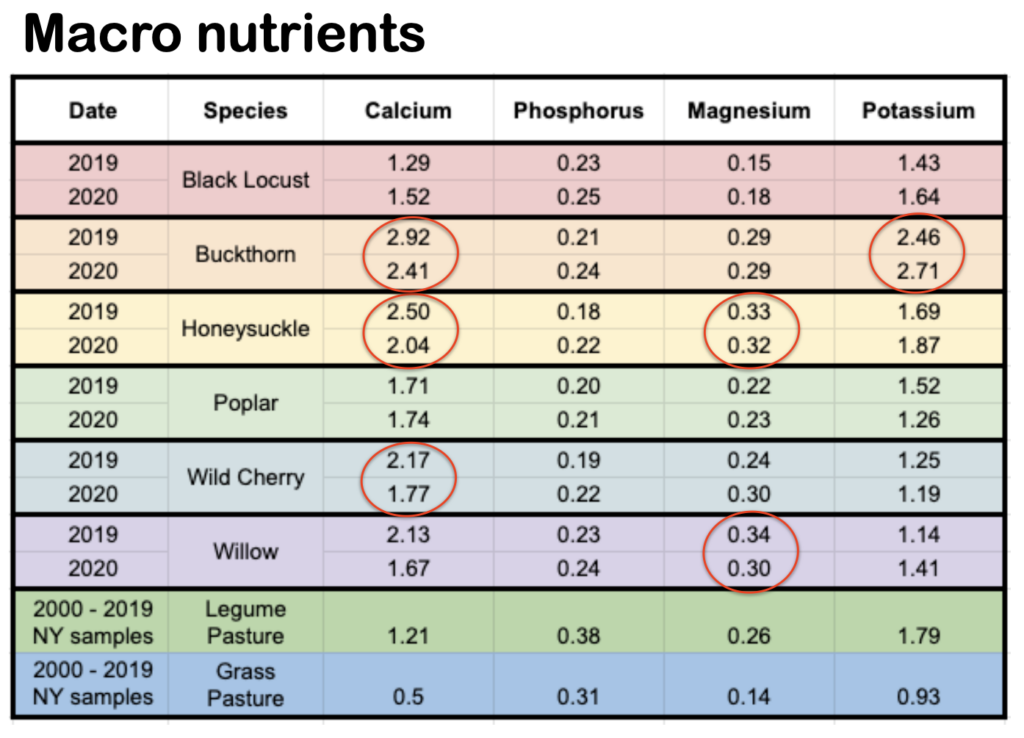

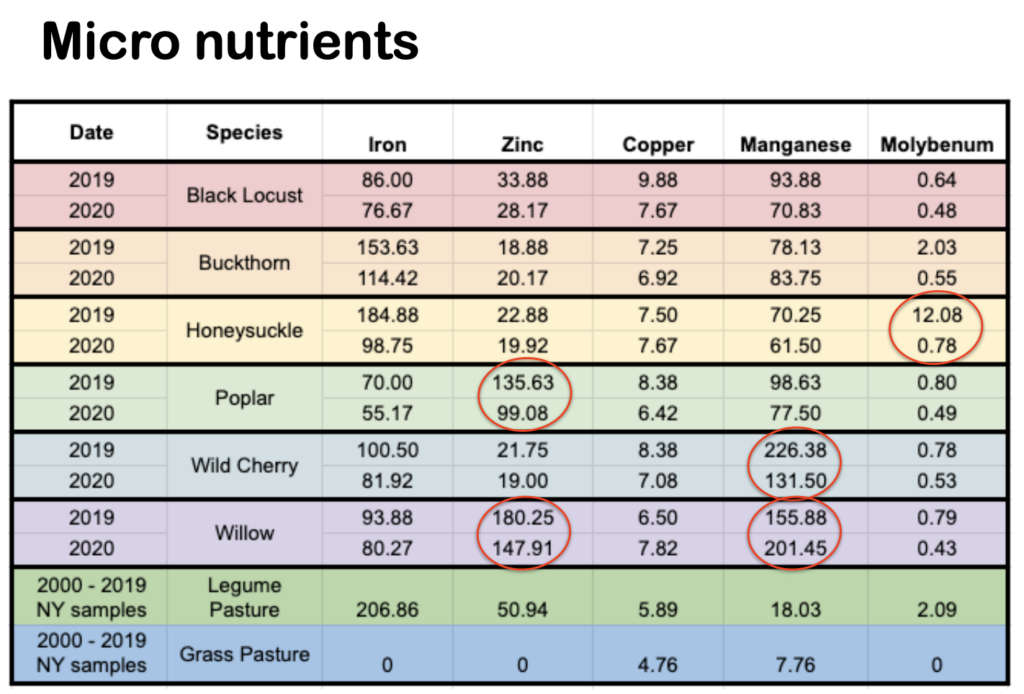

One claim often made about woody browse are the increase in nutrients animals gain from consuming the plants. It follows that woody species in our study certainly offered better values for some macro (Table 3) and micro (Table 4) nutrients (circled in red):

Table 3: Average values for Macro elements

Notable leaders in these macro nutrients include:

Calcium: Buckthorn, Honeysuckle, Wild Cherry

Magnesium: Honeysuckle and Willow

Potassium: Buckthorn

Table 4: Average values for Micro elements

Notable leaders in these micro nutrients include:

Zinc: Poplar and Willow

Manganese: Wild Cherry and Willow

Molybdenum: Honeysuckle

In particular of note are the two oft hated “invasive” species, Buckthorn and Honeysuckle, which demonstrate excellent nutrients available for several categories where traditional forage is lacking. This suggests there may be some benefit to managing these species in the landscape as forage, rather than aiming to eradicate them entirely. Our farm has certainly changed perspective in this regard.

Nutritional Trends over Time

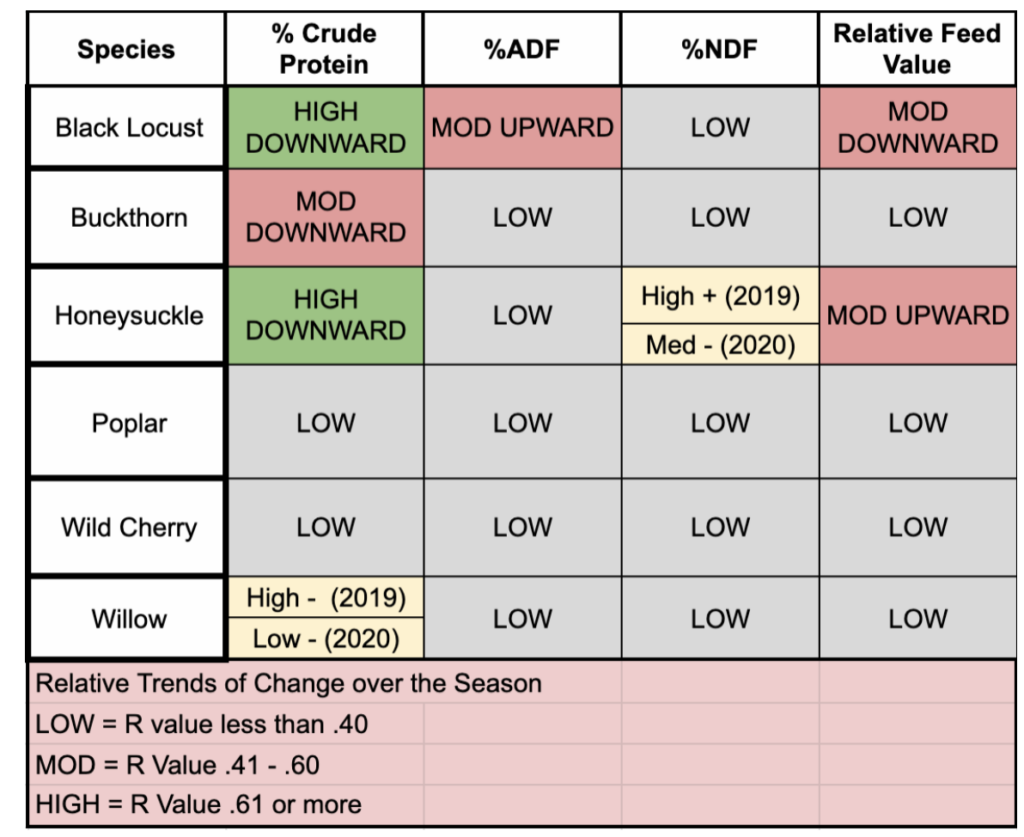

Knowing that on average, tree fodders offer some nutritive value with specific species offering elevated CP, macro and micro nutrient levels, our next research question was to determine what values, if any, fluctuated during the course of a growing season. While after the first year it appeared that some trends might be predictive based on the data, after two seasons it was clear that some of the initial patterns we articulated in our year one report did not hold up. Using R-value analysis further confirmed that trend lines didn't support a strong correlation between the timing of season and the increase or decrease of a certain component of the forage analysis. (Table 5)

Table 5: Results of R-value analysis for evidence of trends (increase or decrease) over the grazing season.

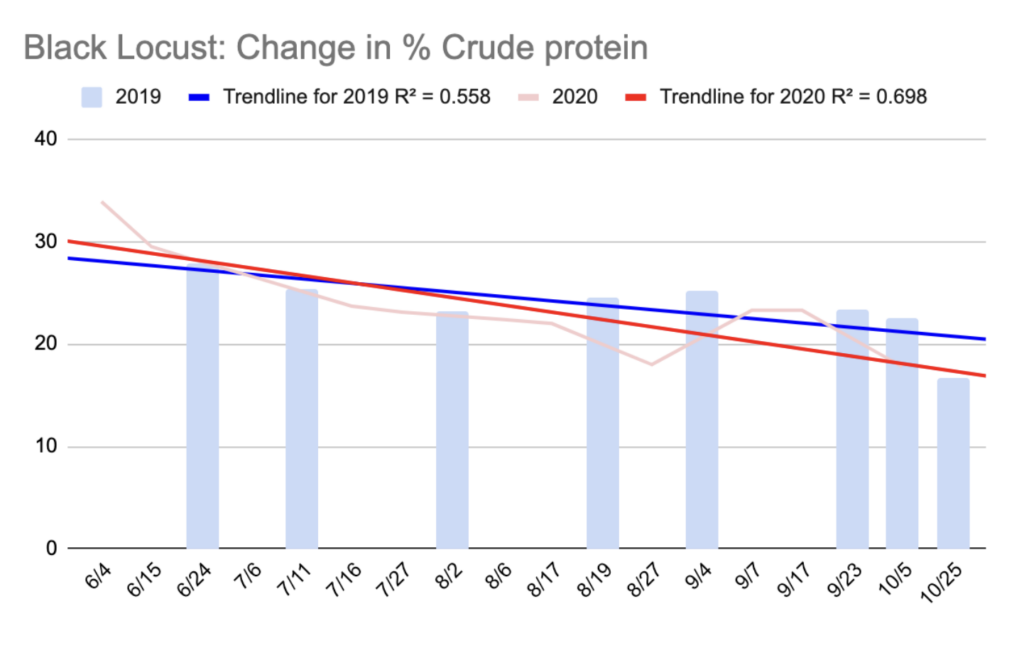

A few examples of this analysis follow here. One of the strongest trends that was graphed was the decrease of crude protein in Black Locust over the course of the season. The data demonstrates an extremely high protein content in June (around 30%) but even at the end of the season in October CP rates are still quite high (18 - 20%). This trend suggests that Black Locust offers an excellent high protein source throughout the season, and in spring can offer a boost or also potentially the risk of bloat from overfeeding.

Table 6: Trends in Black Locust and Crude Protein over the Grazing Season

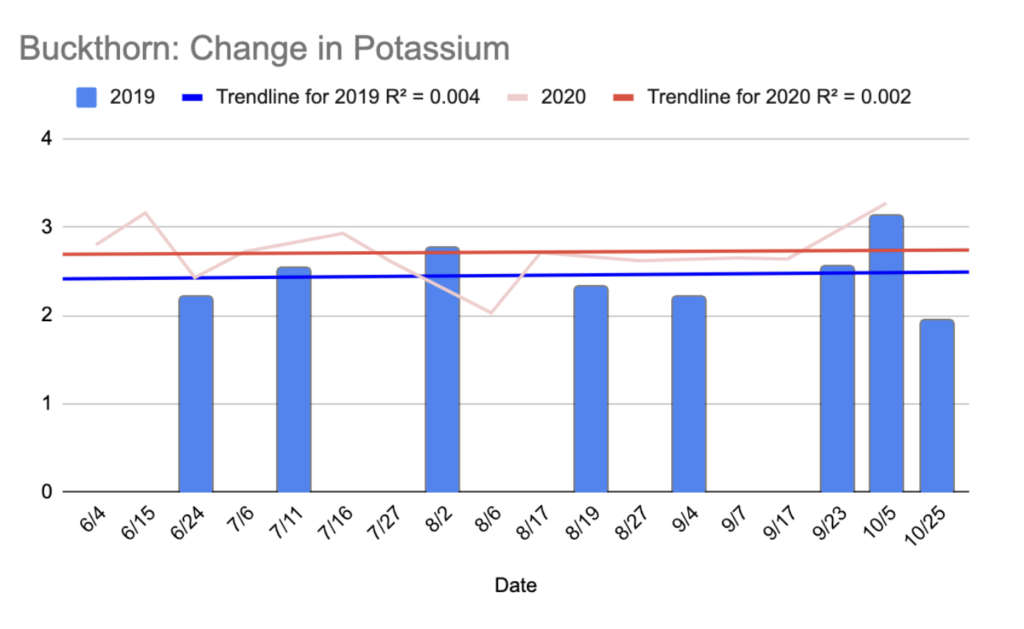

Another example comes in graphing the Potassium in Buckthorn (Table 7), which doesn't offer any significant trend. The values for potassium are relatively stable, and the fodder would offer a good source of the nutrient at any point in the grazing season.

Table 7: Trends in Buckthorn and Potassium Levels over the Grazing Season

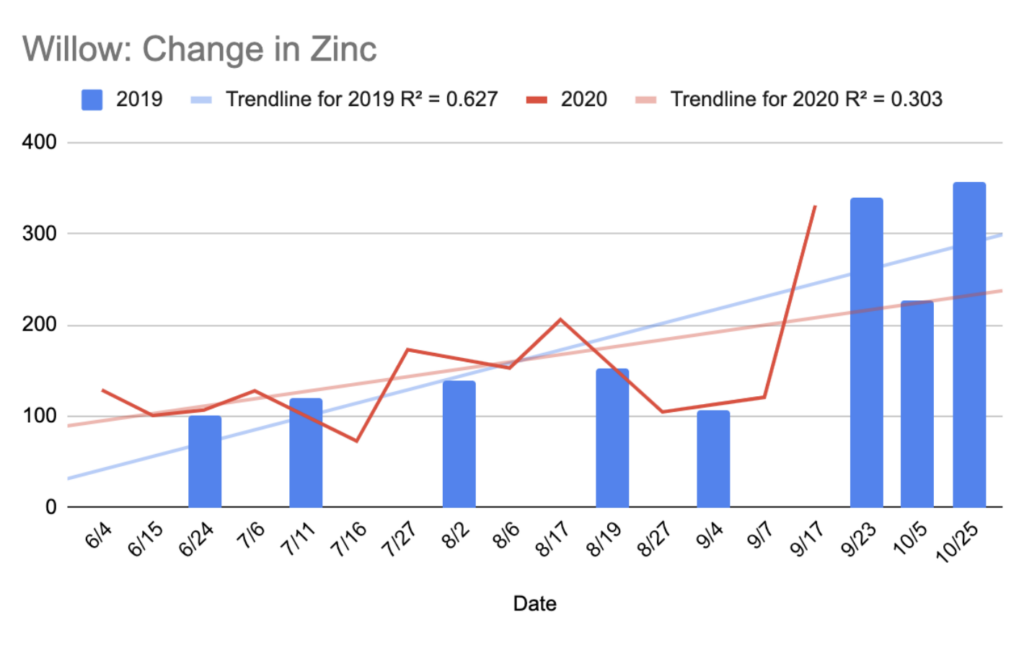

One final example is in the trends of Zinc in Willow over the season. (Table 8) While not a strong trend throughout the course of the season, there appears to be a significant spike in zinc concentration toward the end of the season, when leaves are preparing to drop. While this spike might seem "good" or "bad" potentially, the numbers fall within the acceptable range (toxic levels for sheep are at 750 ppm or above according to Campbell, 1979) and even the lowest values offer ruminants a sufficient amount of the mineral. Thus, there is not a substantial advantage or disadvantage in when willow is fed during the season.

Table 8: Trends in Willow and Zinc Levels over the Grazing Season

As we examined trends for various components of the forage analysis, there was not a clear trend for most of the species and the numerous measurements except in a few cases. Further, it was clear in all cases that values tended to fluctuate within acceptable ranges, and therefore the seasonal timing of feeding tree fodders (at least these species) does not seem to offer relevance to management. We can conclude with the overall assessment that all tree fodders offer good nutritional value, with some having higher crude protein (Black Locust and Buckthorn), and each having a unique set of macro and micro nutrient values, offering something different from each other.

This research project aimed to learn if various tree fodders were good sources of feed and if seasonal timing mattered in feeding them. The results indicate that each of these species offers a good source of nutritional feed, but that timing doesn't significantly matter in their use as a fodder.

In our analysis and discussion with experts on ruminant nutrition, it should be mentioned at the outset that the general consensus is that forage analysis for any material is considered to be highly site and season specific. Therefore, readers of this report should value some of the broad concepts and conclusions from this study, but not take the numbers as exact reference points for their own context. Rather, one should consider what questions they might want to answer about feed value, and conduct site specific forage analysis to help determine if a given species can offer solutions.

With that said, our key findings from this project are:

A. Tree Fodders offer a valuable supplement and emergency food supply for grazing livestock. They are not likely from a management perspective to replace grass and legume forages, but rather offer more nutrient-rich options to a diverge livestock grazing diet.

B. All tree fodders we studied had good relative feed, ADF, and NDF values, indicating they are viable feeds for livestock.

C. Each species brings something different to the table, and not one better than the other. Together they offer a diverse diet to complement grass and legume forages.

D. Macro and micro nutrients are more concentrated in some species versus others, and they flux over the season in complex ways.

E. There were not significant trends or timing deemed critical in feeding these species, as even the lower values were sufficient to meet nutrition needs.

F. Some mineral concentrations are so high there may be some need to have concern with toxicity. In our analysis none of the forages with exceptionally high numbers presented clear toxicity concerns, but is is important to share this as a potential consideration. Feeding fodder in moderation is always recommended.

G. Each species has their own unique profile:

Black Locust is highest valued for its high crude protein content which declines over the season, as well as values for Potassium (little change during the season) and Manganese highest in early July but also spiking in early Sept and Oct, with lowest values of ADF and NDF from early August through early September.

Buckthorn offers a good crude protein content, along with elevated levels of Potassium, Calcium, and Iron, which are highest in the latter end of the season (early October) while NDF and ADF are lowest in September.

Honeysuckle offers a great source of Calcium and Magnesium which is highest toward the end of the season, and Iron which appeared highest in July.

Poplar provides good levels of Calcium, Zinc, and Manganese. While the calcium is greater in the end, the levels of Zine and Manganese appear relatively dispersed through the season, though since its contribution as far a calcium is not as significant as other species.

Wild Cherry’s contributions are Manganese and Calcium, though this foliage doesn’t stand out substantially in comparison with the others, and so it may not matter as much. It’s pretty low value.

Willow is a nutrient sink, offering good values for Calcium, Magnesium, Zinc, and Manganese.

The results give us a compelling reason to continue to develop efficient systems to propagate, plant, manage and feed most of these species in our farm landscape. Forage analysis did prove to help us better understand the benefits, and could be extended to other species we want to learn about, without the need to test so intensively. Testing a new species at the beginning, middle, and end of the season would offer a reasonable snapshot of its feed value.

From a management perspective, the results support our plans to further plant out willow, poplar, and black locust extensively on the farm, species which also meet other objectives within our stewardship goals. We also will continue to manage honeysuckle and buckthorn to reduce their spread but also to provide robust sources of fodder for lean times (drought).

Education & Outreach Activities and Participation Summary

Participation Summary:

In addition to our on site investigations, we completed a literature review for each species to develop a species profile including history, range, and any documented uses for the species we explored, as well as tree fodder management as a whole. We engaged in a review through google scholar, internet searchers, conversations with scholars and practitioners, and access to the NYS Agricultural Library collection. Searches sought to find information on global use and history of the six species, as well as any research that specifically offers data around use as fodder. Resources were compiled using Zotero. This is publicly shared along with a summary write up on the website.

We have reached a wide audience with several events to share our growing knowledge of Tree Fodder during this grant cycle. Our farm hosted an online course in February 2020 in partnership with the National Organic Skillnet (Ireland) and September 2020 in partnership with the practical Farmers of Iowa, with a total of 107 students enrolled over the two offerings. As part of the courses we engaged in five consultations with farmers around silvopasture opportunities for their site. We also engaged in public presentations with Food Animal Concerns Trust (Oct 26, Nov 2, Nov 9 2020) on silvopasture and woody fodders and the species studied in this were discussed in all of them. We presented twice for the Ecological Farmers Association of Ontario conference in December 2020 and for the Vermont Grassfed Conference in January 2021. The SARE reporting site has been featured since January 2020 on our SilvopastureBook.com website, which had 5,515 site visits and 3,055 unique visitors within the entire duration of the project.

Our capstone event was a virtual Tree Fodder Seminar we organized on Dec 10, 2021 with guest speakers Lindsay Whitstance (Organic Research Centre), Eliza Greenman (Hog Tree Consulting) and Ashley Conway (University of Missouri). Topics we covered included the use of tree fodder at Wellspring Forest Farm and a summary of grant results, tree fodder for animal well being, mulberries as a fodder tree, and considerations for nutritional analysis of tree fodder. Since these Northeast SARE grant funds supported our efforts to organize the host the event, we opted to offer a sliding donation for attendees which was entirely contributed to the Community Solidarity Agroforestry Fund which provides free trees to BIPOC, indigenous, and community led organizations around the US. Recordings from the event are posted to our YouTube channel have had over 870 views since being posted.

In lieu of a print or PDF guidebook we originally planned in the proposal, we opted to publish a more accessible website ( "Tree Fodder" menu item at www.SilvopastureBook.com) that includes an article summary of Tree Fodder usage, link to the Northeast SARE project report, an open source ZOTERO library of references collected during the project, and embeds of the videos from the tree fodder seminar.

Learning Outcomes

- Understanding the definitions and historical use of Tree Fodder

- Learning about nutritional considerations and feeding patterns of common Northeast Tree Fodder species

Project Outcomes

- Increased awareness of the benefits tree fodder can provide to grazing systems

- Increased appreciation of so-called "invasive" plants in the landscape that have fodder value (buckthorn, honeysuckle)

- Decreased concerns of "when" to feed tree fodder to maximize any sort of benefit (since there is benefit in feeding anytime during the season)

Given that the sampling process was relatively straightforward in this project, the methodology resulted in valuable data that confirmed the nutritional value of woody fodders in grazing systems and did not discover any meaningful trends to suggested optimal feeding time, at least for fresh use of leaf material and for the species we sampled.

This is not to say that timing may not matter in some circumstances. For instance, in literature review it was clear that leaf fodder harvested to ensile or store for winter has some traditional harvest windows that appear critical, yet much of this is based on tradition or generalized knowledge, and is not usually specific to species. For more discussion of storage of tree leaves see FNE18-897.

Further, certain species may have trends or accumulations of nutrients that may or may not prove important to graziers. It comes down to specific goals each grazier may possess. For our purposes, we wanted to know if the trees we were routinely feeding our sheep and that they seemed to enjoy were in fact, palatable and nutritious. This was a clear result for us, and we can proceed feeding with confidence of the general benefit tree fodder offers.

Where more work is needed is in the complex and intersectional nature of animal nutrition, whether it be to target fodder to specific deficiency in a diet, or to perhaps avoid over accumulation of a nutrient. It is not our skillset (nor desire) to dive deep into all the nuances of nutrition, but rather to continue to seek solutions that more generally improve the health and habitat of our grazing animals and also increase ecological health of our farm landscape. We would love to learn more from others who can better articulate the finer details of grazing animal nutrition.

One last factor is that we only sampled just six species of the hundreds or thousands that could be utilized as fodder in the landscape. More species need to be assessed, on more farms, in more studies over time. Beyond just "is this nutritious"? and "how so?" lie more difficult questions around the best methods to manage resprout and rotational grazing to ensure woody plants can recover adequately from animal impact and to sustain and even increase total yields over time. A collective effort to discover more management practices could bring tree fodder from merely a small percentage of supplemental feed to becoming a truly substantial portion of livestock diets.