Final Report for GNC15-209

Project Information

The successful development of a rotational grazing program on public grasslands in Wisconsin will depend in part on the willingness of beef producers to rent public land. This project uses contingent valuation (CV) survey data and a focus group to identify (1) what beef producers are excited and concerned about regarding pasture rental broadly, and public lands, specifically; (2) desirable contract terms from the producer perspective, how producers feel about renting public land, and the types of producers who would be willing to rent public land; (3) knowledge of where interested producers are generally located; and (4) characteristics of interested producers. We found moderate producer interest in renting land for rotational grazing, with 15 to 25% responding affirmatively. As expected, grass-dominant pasture was the more popular of the two pasture types. For that rental opportunity, we expect younger producers with larger farms and less diverse operations to be interested. Similarly, for shrub-dominated pasture rentals, we expect that producers with relatively less pasture to be more interested in participating. However, median willingness to pay estimates on a per-acres basis were positive for producers currently practicing rotational grazing and with land rental experience, but slightly below current rental rates for private pastureland. The establishment of a public land grazing program may therefore offer benefits for these producers. Future research should concentrate on “hot spots” or mapping the overlap between producer interest in a public grazing program and the locations of viable public land.

Introduction:

Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR) land managers face resource constraints that challenge them to meet conservation land management goals. Increasing rates of woody species encroachment interfere with conservation of the state’s grasslands; threatening rare grassland species, upland game species that utilize grasslands, and other ecosystem services of value to the public. Additionally, beef producers cite land access as an important constraint to their operations, especially for beginning farmers. Research has shown managed, rotational grazing to have positive ecological benefits on grasslands such as control of nonnative grasses and annual vegetation, and improved biodiversity and soil infiltration rates. Grazing public grasslands offers a win-win opportunity for beef producers and WDNR land managers, but is a relatively untested model in Wisconsin.

This project contributed to a larger, USDA Hatch-funded research project focusing on the opportunities and challenges to grazing public land in Wisconsin. The larger project investigates the agronomic and biological impacts of grazing on the landscape, as well as how best to facilitate public-private partnerships between graziers and public land managers. This SARE project focused on the producer perspective of the opportunities and challenges to grazing public land in Wisconsin.

Through a contingent valuation (CV) survey, focus groups, and education and outreach, this project derived and shared information on beef livestock producer demand for renting pastureland. Additionally, this project provided data in the following areas: (1) What beef producers are excited and concerned about regarding pasture rental broadly, as well as concerns specific to public land; (2) desirable contract terms from the producer perspective, how producers feel about renting public land, and the types of producers who would be willing to rent public land; (3) knowledge of where interested producers are generally located; and (4) characteristics of interested producers.

This information will allow land managers to better design grazing programs based on producer needs and constraints. Grazing brokers, grazing associations, and other interested parties are able to use the information to facilitate partnerships between beef graziers and public land managers. In the long-term, information collected during this project may contribute to eventual use of grazing as a land management tool on public land.

There were four learning outcomes and two action outcomes intended by the project. The learning outcomes were (1) Beef producers learn what fellow producers are excited and concerned about regarding pasture rental broadly, as well as concerns specific to renting public land. (2) Beef producers and land managers know desirable contract terms from the producer perspective, how producers feel about renting public land, and the types of producers who would be willing to rent public land. (3) This knowledge increases public land manager confidence in grazing as a land management tool while simultaneously increasing producer willingness to engage in such partnership. (4) Another result of the project is knowledge of where interested producers are generally located which will help with the brokering of public-private partnerships.

With respect to the action outcomes, a short-term outcome was that grazing brokers, grazing associations, and other interested parties facilitate partnerships between graziers and public land managers using the information gathered from the project. A long-term outcome was the use of grazing as a land management tool as a result of changes in practices by both producers and public land managers.

Research

This project used three main methods for achieving its outcomes: a survey of beef livestock producers, a follow-up focus group, and outreach and dialogue based on our findings. The third method, outreach and dialogue, is described in detail in its own section of this report.

SURVEY

Sample acquisition and survey administration

The survey was sent to non-dairy cattle producers across Wisconsin. The selection process followed a stratified design based on herd size and whether a producer checked the “managed intensive grazing” (MIG) box on the 2012 US Census of Agriculture. Following the US Census of Agriculture, we used seven herd size strata: 1-19 head, 20-49 head, 50-99 head, 100-199 head, 200-499 head, 500-999 head, or 1000+ head. Producer selection relied on a confidential list frame managed by the National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS). The final sample consisted of 1,172 farmers, 22% of which checked the “managed intensive grazing” box. Our analysis uses 142 responses from active beef producers for an effective response rate of 12% after removing ineligible returns. The survey was mailed twice, on February 8, 2016 and March 14, 2016 by the NASS.

Contingent Valuation Module

Data on stated land rental intentions comes from a contingent valuation (CV) module in the survey questionnaire. The module asked respondents whether they would rent any land for MIG at a given offer price, and if so, to specify the number of acres they would rent and what type of cattle they would put on the land. The module included an introduction, description of what is provided and not provided by the land manager, a list of grazing requirements, grassland composition and contract length, as well as a final reminder that the grazier must adhere to the grazing requirements if they accept a contract and decide to rent any acres. While grazing rental decisions are complex and require a grazier to consider a variety of variables including distance from their farm and infrastructure availability, sufficient details were provided to allow the respondents to form a personal expectation of profitability and other tradeoffs to make their demand decision. Additionally, we wanted to test farmer willingness to rent based on the grassland quality and grazing restrictions without explicitly saying “public land.” Therefore, we worked with the public land managers to ensure that the grassland descriptions and grazing restrictions were accurate for typical public grassland in Wisconsin, but we did not name the lands as explicitly public in the CV module. Later in the survey we asked attitude questions specific to public lands.

The module included parallel questions for grass-dominated grassland and shrub-dominated grassland, such that the respondent could choose to rent acreage for one, both, or neither type of grassland. Respondents indicated their willingness to rent by agreeing to rent acreage under a given contract scenario. The decision to rent was voluntary and elicited via the DB-DC format. The first question was identical for all respondents and asked, “At a price of $[initial offer price]/acre, would you rent any acres to graze cattle under this scenario?” The second DC question varied depending on the response to the first. If they said yes, the offer price in the second question increased. If they said no, the offer price in the second question decreased.

Three questionnaire versions were used that were identical except for the rental prices offered. Each version had a low, medium, or high range of offer prices. This was in order to capture a more accurate range of farmer reservation prices. Each respondent was assigned at random to a questionnaire version. The range of prices was determined through extensive conversations with grazing professionals from around Wisconsin. The three offer price sets were approximately evenly represented in the survey returns.

Following the initial enrollment questions, debriefing questions asked respondents to specify how many acres they would rent, what class of animal they would put on the pasture, the maximum distance they would travel to graze their cattle under the grazing opportunity, and if they would still rent at the agreed price if they had to provide interior and perimeter fencing. These debriefing questions were asked once per grazing contract scenario conditional on enrollment and tied to the offer price at which the respondent first agreed to enroll. These questions helped us understand how the respondents plan to use rented acreage (e.g. what type of cattle would be grazed), how many acres respondents were interested in, and how distance and infrastructure may affect their decision to rent. Additionally, asking debriefing questions displays “commitment value” or credibility by having respondents engage more deeply with the survey (Carson et al. 2001).

Data analysis methodology

- Non-response analysis

Using additional non-responder data provided by NASS from a previous survey, we tested for significant differences between survey respondents and non-respondents on the following variables available to both groups: age, sex, share of income from farming, retirement status, management intensive grazing (MIG), total number of cattle head, rental experience, total farm acres, total pasture acres, proportion of total pasture acres to total farm acres owned, year the respondent began farming, and years farming. To further check for evidence of differences between the groups, we ran a probit (binary regression) with responded as the dependent variable.

- Sample selection model

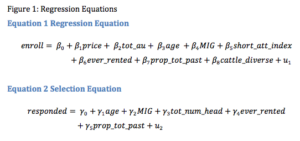

To control for sample selection bias, we employ a Heckman selection model where the impact of selection bias is explicitly incorporated into the estimating equation for willingness to undertake the rental contract (Guo and Fraser 2010). These types of sample selection models involve two equations: (1) the regression equation including factors determining the outcome variable and (2) the selection equation that identifies a portion of the sample whose outcome is observed and the factors that shape the selection process (Heckman 1978, 1979). Equation 1 and Equation 2 (Figure 1) show our regression and selection equations respectively. These both include age, a MIG dummy variable, past rental experience, and the proportion of total pasture acres to farm acres owned; all variables that were available on respondents and non-respondents through NASS. The regression equation includes additional variables that were only available via the survey for respondents. Using this model, we ran a Probit with sample selection and data from all questionnaire versions, and then another Probit with sample selection and data from only the low- and medium-priced questionnaire versions.

- Estimate willingness to pay

Using coefficient estimates from the Probit model with selection with all observations (Model 2), we calculated the median willingness to pay per acre to graze public land of different producer sub-groups.

FOCUS GROUP

A focus group of cattle producers was held on October 15, 2016 in Seneca, Wisconsin to unpack some of the Grazing Public Lands survey results and to collect qualitative data on producer interest in grazing public lands in Wisconsin. There were nine focus group participants with a variety of operation types, all from the southwest part of Wisconsin where grazing is more common. Focus group participants raised a variety of cattle types: Organic dairy, beef heifers, dairy cows, steers, dry cows, purebred cows, feedlot cattle, and calves. Their rental experience varied, with some participants having rented land for grazing in the past and some having never rented. The focus group lasted for two hours during which participants responded to a variety of questions on renting pasture generally, and renting public land specifically.

Carson, R. T., N. E. Flores, and N. F. Meade. “Contingent valuation: controversies and evidence.” Environmental and resource economics, 19:2(2001):173-210.

Guo, S., Fraser, M. (2010). Propensity Score Analysis: Statistical Methods and Applications. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Heckman, J. (1978). Simple Statistical Models for Discrete Panel Data Developed and Applied to Test the Hypothesis of True State Dependence against the Hypothesis of Spurious State Dependence. Annales De L'inséé, (30/31), 227. doi:10.2307/20075292

Heckman, J. J. (1979). Statistical models for discrete panel data. Department ofEconomics and Graduate School of Business, University of Chicago.

SURVEY

Estimation Results

Estimated coefficients for the grass-dominant scenario are shown in Table 1; while results for the shrub-dominant scenario are presented in Table 2. We discuss the second stage results in more detail here, but note that the first-stage response analysis contains many statistically significant results consistent with the non-response analysis above. Those results suggest among other findings that MIG producers were more likely to respond to the survey and that their interest may be essential to the potential for these types of contracts between DNR land managers and cattle producers to advance. The Wald tests for overall model fit are significant at the 5% level across all models and scenarios, except for Model 3 in the shrub-dominant scenario.

From coefficient estimates for the outcome equation, we can identify characteristics of producers who will be most likely to participate in land rental programs for managed grazing. Looking at the Probit results without selection for the grass-dominant scenario (Model 1 in Table 1), the producers who are most likely to participate are younger, already practice MIG, have a positive attitude toward conservation and working with government, have prior rental experience, and less diverse cattle operations. As expected, we also find the land rental offer price to be significant and negatively related to enrollment. For the Probit model with selection for response behavior, we lose significance on all variables except Price and Diversity (Model 2 in Table 1). The lack of statistically significant results may be due to confounding effects of small sample size and low- to zero-enrollment rates at the highest price survey version. The high share of censored observations as a proportion of total observations (about one-third) complicates the model’s ability to distinguish which factors explain the observed variability in participation responses.

Model 3 in Table 1 shows the results for a Probit model with selection that excludes the high price survey version. We believe these results accurately reflect the role of non-price explanatory variables by dropping the observations responsible for this censoring. The difference in statistically significant explanatory factors between Model 1 and Model 3 is recognizable. The third model suggests that producers who will be most likely to participate on grass-dominant land have larger operations in terms of herd size, are younger, and manage fewer types of cattle. Practically, this means someone ten years older is 9% less likely to rent. Herd size is scaled by 10 in this model, so a farm with 10 additional animal units is 0.4% more likely to rent than one with less animal units. Finally, someone with an additional type of cattle is 4.5% less likely to rent. These are not negligible effects from a program design perspective, nor are they surprising. The first two characteristics could easily be identified by those knowledgeable about local cattle producers.

Furthermore, accounting for selection identifies (across both selection models) land rental price, age, and herd diversity as significant factors, but also herd size which was not identified in the Probit without selection. In contrast, it shows no significant effect for prior experience with managed grazing or land rental experience—two variables which are intertwined with, and appear to drive, initial survey response decisions and appear as significant in the Probit without selection. This contrast confirms that accounting for response behavior can lead to markedly different empirical findings in ex-ante analysis of agricultural management practices and land

use options, including the statistical significance of key outreach and policy factors that might be used to inform program design. Note that the correlation coefficient is not found to be statistically significant, which suggests that there are no significant unobserved factors driving the selection process.

When the public land on offer is shrub-dominant, significant producer characteristics differ from the grass-dominant scenario. Starting with Model 1 in Table 2 (without selection), expected participants are producers with smaller pasture area as a proportion of total land. Price is also significant and negatively related to enrollment decisions. Here, selection bias appears to have less impact. The level of significance and magnitude of effect for Price and Pasture are relatively unchanged in the Probit model with selection (Model 2). Considering possible censoring of the outcome variable at high land rental prices, Model 3 shows Attitude as the only significant predictor of producer participation; however, pasture proportion remains significant in terms of marginal effects. Specifically, an increase in the proportion by 10% means a producer is 71% less likely to rent shrub-dominant pasture. In other words, interest in renting shrub-dominant land is highly sensitive to a producer’s access to owned pasture.

The differences between willingness to rent grass-dominant pasture versus shrub-dominant pasture are not surprising. Shrubland provides less quality forage for cattle and so is worth less to a producer. It is also more work; to beat back shrubland may require mob-grazing or another high-intensity grazing method that needs more frequent management. It makes sense that only those producers who are highly pasture-constrained or have some inclination to do conservation grazing would be interested in grazing shrubland at the prices offered in the survey.

Producer Willingness to Pay for Rotational Grazing

Table 3 shows predicted median WTP values on a per-acre basis for subsets of producers with and without prior MIG and land rental experience. When estimated using overall sample averages, WTP values are low and practically similar for both grazing scenarios; however, the WTP shrub-dominant grazing land ($2.74) is unexpectedly a bit higher than the WTP grassdominant land ($1.31) in absolute terms. Other things equal, we would have presumed a higher WTP for the higher-quality grass-dominant pasture due to better forage quality.

When we look at WTP estimates for MIG practitioners, we find a slightly higher median WTP for the shrub-dominant scenarios ($4.94 per acre) and a much higher WTP for grassdominant scenarios ($15.20 per acre). Contrastingly, the non-MIG practitioners are very averse to paying for grass or shrub dominant pasture; The median WTP values are negative implying the majority would require an additional subsidy to participate in a grazing program on public land. For individuals with prior rental experience, WTP values are even higher for shrubland and grassland ($5.72 per acre and $17.12 per acre, respectively). Again, those who do not have prior rental experience appear averse to paying to graze on either grass or shrub-dominated land. The highest WTP comes with individuals who have both prior rental experience and MIG experience ($7.92 per-acre for shrub-dominant and $31.01 per acre for grass-dominant).

For producers who currently rent, we could expect their WTP to equal the opportunity cost of land access, or the current land rental rate. If a producer is both a MIG practitioner and has prior rental experience, their willingness to pay in our model is $31/acre, which is just below the 2016 state average rental price of $35/acre for pasture in Wisconsin (USDA-NASS, 2016).

Overall, higher WTP values from MIG practitioners and experienced renters imply utility gains from renting under both scenarios by these types of producers. The higher WTP among MIG practitioners and experienced renters indicates that their utility gains from expanded access to grazing land is greater than non-MIG and those who do not currently rent.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. “Cash Rent Survey.” National Agricultural Statistics Service, 2016.

FOCUS GROUP

The focus group results provided further evidence that producers are interested and willing to make tradeoffs based on the specific context. When thinking generally about renting land (public or private) participants consider infrastructure, forage quality, distance of the land from their farm, whether someone can help keep an eye on the cattle, and their operation’s needs. All of these variables are flexible however, depending on the situation.

When deciding how many acres to rent, participants said they consider how many animals would make it worth it to go and check on them, what their financial constraints are, whether they would be able to control the entire area, and the quality of pasture. There was a lot of discussion around preferring to control an entire pasture versus sharing it with another grazier, leading to a willingness to pay more in order not to share. They also mentioned that they almost always base the decision on the cattle they already have; Only in rare market circumstances are producers willing to buy more cattle to fill a large area of land. When deciding what class of cow to put on the pasture, producers will put their best cows on the best pasture available, which is often their home pasture. Additionally if it is a dairy operation, dairy cows will be kept close to home while dry cows, heifers, or cow/calf pairs may be kept on a rented pasture. Producers also consider what types of cows are on a neighboring pasture when deciding which class of animals to put on rented land.

The focus group participants had largely positive or neutral feelings about the idea of using rotational grazing as a land management tool on public land. There was agreement that the land manager will need to have a clear idea of their management goals and how they want to integrate grazing on the land. This may include aesthetic goals in addition to management goals. Participants also made it clear that the contract would need to meet their own economic goals and that they would not do conservation grazing altruistically. There were concerns about infrastructure (fencing, water access, and handling facilities), but most participants said they would be willing to work with most situations, including working with a public land manager and spending time educating/collaborating with them, as long as the contract still made economic sense. One of the focus group participants explained that they found the idea of working with a public agency interesting and challenging, and as an opportunity to help change people’s attitudes toward livestock and grazing. There was also a general sentiment that contracts for rotationally grazing public land should have clear specifications and penalties for non-compliance to help ensure the right producers are interested.

Participants provided further insight into concerns about liability and public access to the land. Some potential liability issues mentioned included being near an interstate highway or other busy road (e.g. a car crashes into the perimeter fence and cattle flow out onto the highway), having a bull on the pasture, public land users accidentally leaving gates open, or people petting or picking up calves. The group mentioned a few possible solutions to mitigate these issues: taking out renter’s insurance, clear and detailed signage, and self-closing gates.

Finally, when asked what advice they would give the director of a public grazing program in Wisconsin, participants said they would recommend contracts with restrictions to help ensure appropriate graziers are on the land. They also felt that there would need to be incentives for graziers to make them interested in the opportunity. Similarly, they suggested that there be flexibility in the grazing contract or flexibility within the grazing program to allow for contextual contracts that meet everyone’s needs.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation Summary:

OUTREACH AND DIALOGUE

Outreach and dialogue took place at four main events: (1) a presentation and discussion at the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources; (2) a dialogue at the 2017 Grassworks Conference; (3) a presentation and discussion at a public land manager pasture walk and field day; (4) a public defense of my thesis research; and (5) submission of a manuscript to Journal of Agricultural Resource Economics (JARE).

WDNR Presentation and Discussion

I gave a presentation on the results of the project at the Madison WDNR office on January 27, 2017. There were about 14 individuals in attendance, and the presentation was recorded for use by WDNR employees who could not attend the presentation. The attendees included public land managers, wildlife specialists, a public lands specialist, and more. The information was well-received and attendees asked many questions. After the presentation there was a group discussion relating to the information I had just presented.

2017 Grassworks Conference

Two graduate students and myself facilitated a dialogue between producers and public land managers at the annual Grassworks grazing conference in February 2017. There were about 25 individuals in attendance. I presented some of the key findings from my research, and then attendees were split into groups and asked to deliberate on the findings using discussion questions.

Public Land Manager Field Day

The results of my research were presented to a group of about 30 WDNR public land managers and wildlife specialists on August 11, 2016.

Public Thesis Defense

The defense of my thesis was public and there were producers, public land managers, grazing brokers, university researchers, and employees from the Department of Agriculture, Trade, and Consumer Protection. I gave a detailed presentation of the results from my research, followed by a question and answer period.

Manuscript submission to JARE

A manuscript, “Willingness to Rent Public Grasslands for Rotational Grazing in Wisconsin: The Importance of Non-Response Behavior” was submitted to the Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics in February 2017. The article has been reviewed and returned to the authors with needed edits, including additional empirical work. New empirical work is currently being done and the article will be re-submitted to another journal hopefully in autumn 2017.

Project Outcomes

Research results can be used by WDNR to inform program design and efficient contract drafting. Additionally, if the needs or constraints posed by graziers are not amenable to WDNR, then land managers will know to pursue other solutions. For graziers, the research findings will provide insight into how their peers think and feel about renting land, suggest contract norms, and yield information regarding barriers and opportunities that may help producers feel more comfortable with the idea of partnering with public land managers. Finally, grazing brokers, grazing specialists, cattle networks and others will have an increased ability to facilitate partnerships. Land managers may not have the information or capacity to seek out interested graziers, design suitable contracts, or provide infrastructure. Therefore these liaisons play a critical connective role and increasing their capacity to play this role will increase the efficiency and success rate of partnerships.

The research also identified the characteristics of interested producers that can help land managers target certain areas and producers more effectively. Paired with information regarding WDNR land availability, we will be able to locate hotspots of potential grazier interest and available WDNR land to efficiently broker partnerships.

Finally, permitting grazing on public land represents a new potential tool for grassland ecosystem management in the U.S. Upper Midwest, as compared to costly alternatives like mowing, haying, or burning. Public grassland managers and other stakeholders can use these findings to target recruitment efforts at producers who are likely to participate and hold positive WTP values. Additional incentives such as fencing or transportation subsidies could further increase participation.

Comments on specific intended outcomes

(1) Beef producers learn what fellow producers are excited and concerned about regarding pasture rental broadly, as well as concerns specific to renting public land.

As the outreach section will describe in more detail, this outcome was achieved mainly during a 2017 Grassworks dialogue session. The results of this project were presented to producers who were then given the opportunity to discuss their thoughts. In addition, producers in attendance at my public thesis defense were also exposed to these ideas and given an opportunity to ask questions.

(2) Beef producers and land managers know desirable contract terms from the producer perspective, how producers feel about renting public land, and the types of producers who would be willing to rent public land.

As the outreach section will describe in more detail, this outcome was achieved mainly during a 2017 Grassworks dialogue session. The results of this project were presented to producers who were then given the opportunity to discuss their thoughts. In addition, producers in attendance at my public thesis defense were also exposed to these ideas and given an opportunity to ask questions.

(3) This knowledge increases public land manager confidence in grazing as a land management tool while simultaneously increasing producer willingness to engage in such partnership.

As the outreach section will describe in more detail, this outcome was achieved mainly during two presentations to WDNR personnel. The results of this project were presented to WDNR employees who were then given the opportunity to discuss their thoughts and ask questions. In addition, public land managers in attendance at my public thesis defense were also exposed to these ideas and given an opportunity to ask questions.

(4) Another result of the project is knowledge of where interested producers are generally located which will help with the brokering of public-private partnerships.

This outcome ended up falling outside the scope of the project. It is suggested as future research.

(5) Grazing brokers, grazing associations, and other interested parties facilitate partnerships between graziers and public land managers using the information gathered from the project.

This outcome is true for a number of pilot partnerships currently taking place. They have been briefed on the findings of this project and are working with graduate students to utilize the findings in their own partnerships.

(6) A long-term outcome will be the use of grazing as a land management tool as a result of changes in practices by both producers and public land managers.

This is a long-term outcome and therefore outside the scope of this project.

Areas needing additional study

To further inform program feasibility and cost-effectiveness, future research could investigate producer willingness to travel to graze public land, where the public land is located, and how many graziers are within the radius. This may mean a targeted effort initially in regions with higher densities of younger cattle producers, larger herds, and current MIG methods. These characteristics are available from public sources, and could be used to identify prospective county- or township-level candidate locations.