Final report for GNC21-316

Project Information

Identifying determinants and opportunities for expansion of organic small grain acreage in the Upper Midwest

Whether for human consumption or livestock feed, growing small grains benefits farmers, the land and communities. Cereal crops such as wheat, barley, rye and oats can diversify farmers’ financial risk, improve soil health and water quality, and support regional grain supply chains. While these grains have been missing from the local, organic foods available to consumers, a growing interest in high quality flours and emerging artisanal brewing and distilling sector are creating a niche market for local organic grains. According to data from the USDA, acreage of organic rye, oats, and wheat have increased in the region in the last decade, while conventional acreage has been stable or in decline. This growth underscores the promise for organic small grains production in the Upper Midwest. As sales of organic commodities grew 31% nationwide between 2016 - 2019 (USDA 2019), farmers should be considering the market potential for organic small grains.

The growing interest in the integration of small grains as part of a diversified organic cropping system is reflected in a substantial body of agronomic research focused at the field-level to find ways to raise small grains more efficiently and profitably. While use of improved genetics and production techniques are important, no existing work has examined the array of socio-economic factors determining whether a farmer grows organic small grains. Consequently, few resources exist detailing how to support the organic small grains industry.

This research proposes a combination of quantitative and qualitative participatory methods to provide a comprehensive understanding of how the use of organic small grains can be increased in the region. Through a farmer survey, we will examine a broad range of factors that may be associated with the use of small grains including individual, farm-level, geographic, institutional and market factors for a holistic assessment. We will focus on the state of Wisconsin– a state with significant potential for small grains production due to its agronomic conditions, prevalence of integrated livestock operations and growing artisan baking, distilling and brewing sectors– for targeted solutions on how to support organic small grains. We will then hold focus groups to identify institutional changes and strategies to increase support to organic small grain growers and increase acreage of small grains throughout the region for a more resilient and sustainable agriculture.

Learning: Identify the barriers and drivers of adoption of organic small grains in Wisconsin, and the opportunities to increase their use. Agricultural educators and institutional influencers (agency, market, and education leaders) increase knowledge of these barriers, drivers and opportunities and recommended actions to expand adoption. Farmers gain knowledge of small grain benefits, and the factors associated with profitability on other organic small grains operations.

Action: Institutional influencers use project findings and recommendations to inform strategic investment and policy making. Upper Midwestern farmers adopt diverse rotations with organic small grains.

System-wide: On-farm economic and ecological resilience increases region-wide through greater adoption of small grains in organic cropping rotations, resulting in stronger regional small grain supply chains.

Cooperators

- (Researcher)

Research

This project uses a mixed methods design to triangulate and enrich the ways in which we understand farmer decision making and the structural and biophysical factors that impact it. For the purposes of this study, we define small grains as barley (spring and winter), Kernza ®, oats, rye (cereal and hybrid), triticale (spring and winter), spelt, and wheat (spring and winter). All components of the study—the survey, focus groups and interviews—were developed in close collaboration with project partners including the Artisan Grain Collaborative (AGC) and the Michael Fields Agricultural Institute. We focused on the states of Iowa, Illinois, Minnesota, and Wisconsin due to their significant potential for small grains production, and growing artisan baking, distilling and brewing sectors. While this research focuses on the role of organic certification in the adoption of small grains, we studied both organic and non-organic farmers. We do so to understand how organic certification impacts whether a farmer grows small grains through statistical analysis and to understand how to encourage the adoption of small grains among non-organic farmers given that it is an entry into one of the core tenants of organic systems—crop rotation.

Farmer survey

A farmer survey was disseminated between January and April of 2022 during a time when farmers are most available in the region as they have finished harvesting and have yet to begin spring planting. The survey questions were focused on operational details, the barriers to and drivers of planting small grains, the support programs available to them, beliefs of the benefits of small grains in rotations, and the most reliable sources of information regarding small grains. For those who currently or have grown small grains in the past, we asked about the kinds of markets and contracts they use for selling their grain, and any infrastructure limitations. The survey was pilot tested with a group of farmers from the AGC Farmer Collaborative working group, the project advisory council, and several other farmers.

We disseminated the survey through several routes. First, we sent the survey to 3,125 farmers through post-mail and email using a stratified randomized sample of farmers purchased from the company DTN. We disseminated the survey through post-mail and email to reach a broader population of farmers with varying access to the internet and comfort with email. We limited our sample to those who were farm operators, and to ensure we did not include hobby farmers, we included corn and or soybean farmers who farmed at least 40 operational acres (as opposed to land leased to others or land in pasture) and small grain farmers (those who did not grow corn and or soybeans) who farmed at least 10 operational acres. To ensure equal representation from farmers who had and had not grown small grains, 50% of the sample was composed of famers who grew corn and or soybeans and no small grains, 38.5% were farmers who grew corn and or soybean farmers with at least one small grain, and 11.5% were farmers who did not grow corn or soybeans but grew at least one small grain. We targeted corn and soybean farmers due to their large impact on the landscape as the predominant cropping system in the region. However, we also included a smaller subset of non-corn and soybean farmers who grew small grains to include a wider range of experiences with small grains, given the small number of farmers who grow them in the Midwest.

We sent out 3 waves of contact for each route. For post-mail surveys we sent the survey, and two follow-up post-cards. For the online survey, we sent an email with an invitation to take the survey, one follow-up email, and one follow-up post card. After excluding undeliverable addresses and those no longer farming, we received usable post mail surveys from 219 farmers with a response rate of 25%, and 80 usable online surveys with a response rate of 4%.

Next, after finding the initial results of the post mail and email surveys to be lacking in organic farmers, we sent the survey through two additional online routes: to email addresses from the USDA Organic Integrity database and through the University of Wisconsin Organic Grain Research and Information Network (OGRAIN) listserv. We collected email addresses from the USDA Organic Integrity database for those farming at least one small grain and sent an email invitation to take the survey, one follow-up email, and one follow-up post card. We received usable surveys from 41 farmers for a response rate of 14%. We sent an email through the OGRAIN listserv, a network of farmers in the Upper Midwest growing organic grains, inviting farmers to take the survey. We received responses from 27 farmers for a response rate of 4% using the number of farmers subscribed to the list. While the response rates are low for the online and organic-specific routes of dissemination, we believe that they are acceptable given the difficulty of reaching small grain farmers and organic farmers. Only 8% of farming operations in the states included grow small grains and only 1% are organic (USDA 2017). Our total sample size combining all dissemination routes is 406 farmers.

Focus groups and interviews

Fifteen in-depth, semi-structured interviews and five focus groups were held July to September of 2022. While this is a time when farmers are more engaged on-farm, we timed the interviews and groups to occur during off periods from planting and spraying across corn, soybean, and small grain production. Farmer interview questions focused on the farmer’s experience growing small grains (for current small grains growers), why they stopped growing small grains (for discontinued growers), thoughts on small grain production (for non-small grain growers), and specific questions on markets, infrastructure, government programs, and research and information that could support them to grow small grains. Non-farmer interview questions varied based on the sector of the participants, but generally gauged the barriers and opportunities for small grains production in the region.

Farmers were identified by those who indicated interest in participating on the farmer survey and through partner organizations. Non-farming agricultural professionals were purposefully selected due to their work in or knowledge of small grain production. A total of 39 individuals participated in interview and focus groups. Twenty-three of the participants were farmers: 17 who grew small grains, four who discontinued growing small grains, and three who did not grow small grains. Sixteen non farming agricultural professionals took part including crop insurance salespeople, agricultural lenders, small grain buyers and marketers, small grain millers, academics and advocates working in small grain production, and Cooperative Extension professionals. Interviews and focus group were conducted either in-person, via Zoom, or by telephone and lasted between 25 to 60 minutes. Interview data were analyzed using NVivo software and coded according to an inductive approach that identified reoccurring themes (Corbin and Strauss 1990).

Quantitative Analysis

We ran two regressions to understand the factors associated with whether a farmer grows small grains and the change in profitability after adding small grains to an operation. For the first regression, we used a logistic regression model appropriate for binary dependent variables. Those who grew small grains at some point in the last 6 years were given a 1 and those who had not grown small grains in the last 6 years but had grown them in the past and those who had never grown small grains were given a 0. For the second regression, we used an ordinal logistic regression model suited for ordered dependent variables. Change in profitability is measured as the change in profitability of the farming business as a whole after adding small grains to rotations (changes to input purchases, yields, revenue, etc.). Responses were: reduced my farm’s profitability, very little change to my farm’s profitability, and increased my farm’s profitability (coded as 1, 2, and 3, respectively).

Independent variables included in each regression were chosen based on an iterative process including those that have been shown to be associated with use of diversification practices and conservation practices in existing literature, those that were highly correlated with whether a farmer grows small grains, and those that, when added, improved the model fit. Variables were tested for collinearity with other independent variables in the model and none were found to be problematic. Backward and bidirectional stepwise selection confirmed our choice of those added based on correlation and model fit. We include the state in which the farmer resides in each to control for biophysical variability that may impact decisions to grow a small grain.

Farmers were surveyed from the Midwestern states of Illinois (n=104), Iowa (n=107), Minnesota (n=109), and Wisconsin (m=86). Of the farmers we surveyed, 271 were currently growing small grains as a cash crop or cover crop at some point in the last 6 years, 71 had grown them in the past, but stopped in the last 6 years (which we refer to as discontinued small grain farmers), and 64 had never grown small grains. The average age of farmers surveyed was 61 years old and the average farm size was 671 acres. Surveyed farmers owned, on average, 65% of their land and 47% of farmers raised livestock in addition to crops. In terms of farming practices, 20% of farmers were organic or transitioning to organic and 50% used no till or some form of conservation tillage.

To understand what determines whether a farmer plants small grains, and in particular the role of organic certification and experience of organic farmers, we used two main methods: 1) what farmers themselves report as the barriers and drivers and 2) what individual and farm-level factors are associated in regression analysis with whether a farmer plants small grains. Each method allows us to analyze different but complementary factors that can provide a comprehensive analysis of the determinants of small grains adoption.

Farmer reported results

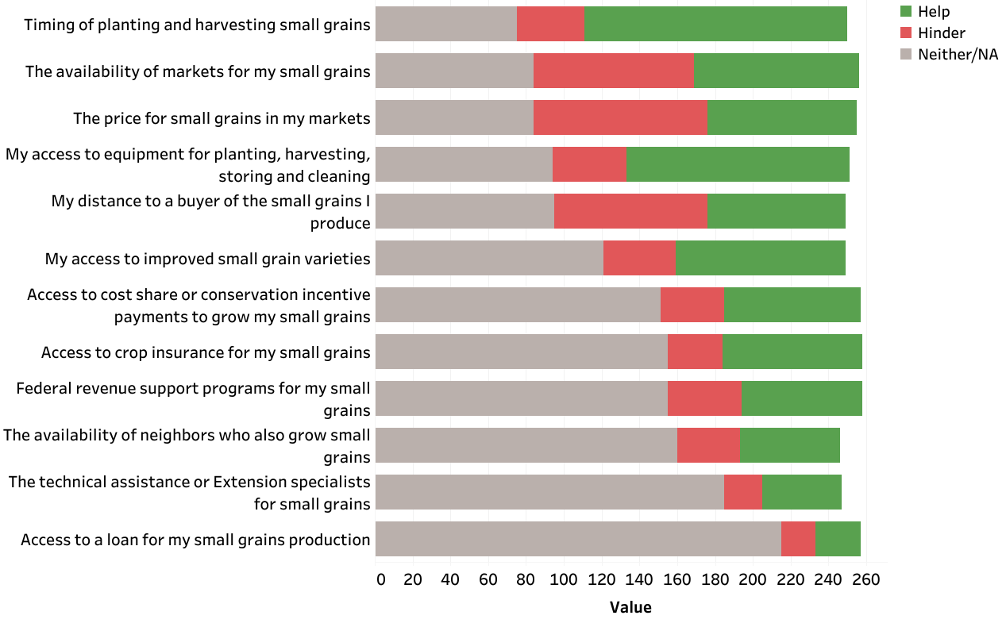

According to small grain farmers, economic factors—the price for small grains in their markets, the availability of markets for their small grains, and the distance to a buyer of the small grains they produce pose the largest hinderance to their ability or willingness to plant small grains, whether for sale or for on-farm use (Figure 1). Economic factors, however, can be both a helping and hindering force, and each were about as commonly selected as factors that helped farmers plant small grains as factors that hindered them. The factors that farmers selected the most as helping their ability or willingness to plant small grains were the timing of planting and harvesting small grains, access to equipment for planting, harvesting, storing, and cleaning small grains, and access to improved small grain varieties relevant to their geographic area or desired markets. The availability of technical assistance or Extension specialists for small grains were not listed commonly as either helping or hindering farmers, suggesting that access to information is not a key factor in a farmer’s ability or willingness to plant small grains.

Of the policy factors, access to crop insurance for small grains, access to cost share or conservation incentive payments for small grains such as EQIP (Environmental Quality Incentives Program) or CSP (Conservation Stewardship Program), and federal revenue support programs for small grains such as Price Loss Coverage (PLC), Agriculture Risk Coverage (ARC), and the Marketing Assistance Loan program (MAL) were listed as the 6th and 8th and 9th most important factors (out of 12), respectively, that helped farmers to grow small grains. Each of these policy factors were more commonly listed as helping farmers comparing to hindering them. Access to a loan for small grains production was not commonly selected as helped or hindering, suggesting that farmers do not face barriers to obtaining financing for small grains operations.

Figure 1. Self-reported factors that help or hinder small grain production among small grain farmers

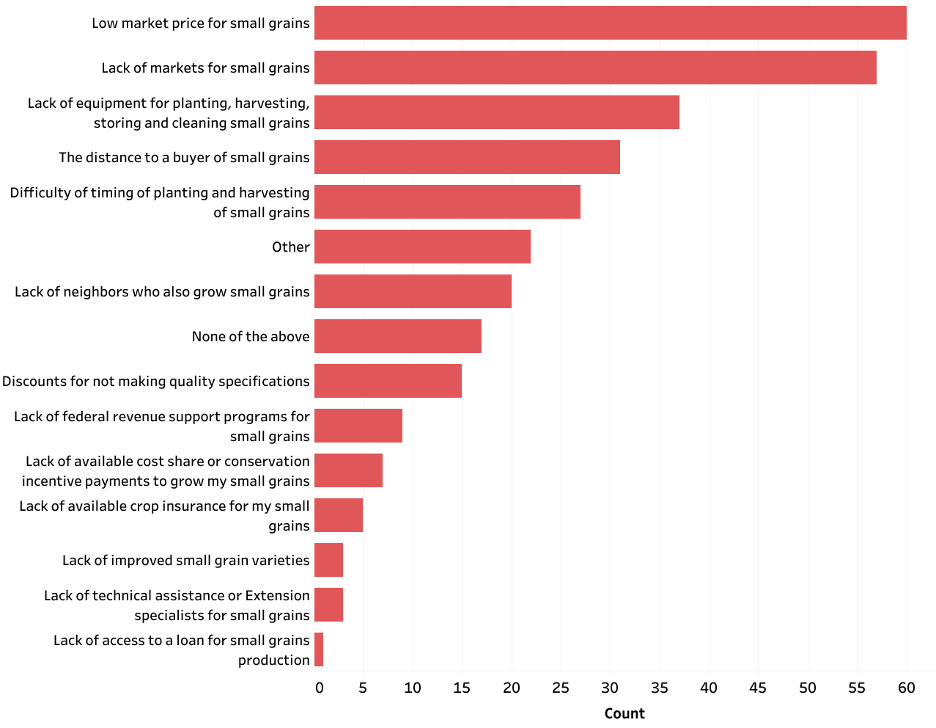

Farmers who discontinued their small grain production and those who have never grown small grains reported a lack of markets for small grains and a low market price as the most common barriers to production (Figure 2). Lack of equipment for planting, harvesting, storing, and cleaning, and distance to a buyer were also frequently listed as barriers. Like small grain farmers who did not commonly select policy factors as hindering, discontinued and non-small grain farmers did not commonly list a lack of federal revenue support programs, cost share, crop insurance or loans as barriers to production.

Figure 2. Barriers to small grains production among discontinued and non-small grain farmers

Note: The most common responses in the category “other” were lack of livestock, age, and low profitability.

Regression results

Results from a logistic regression to understand the factors associated with whether a farmer currently grows small grains is shown in Table 1. Regression results add to the farm-reported factors that determine whether a farmer grows small grains by testing whether individual and farm-level factors are statistically associated with the decision to grow small grains. We find that several factors are statistically significantly associated with whether a farmer grows small grains. The most important factors are whether the operation was certified organic (p=0.00001), whether the farm raised livestock for on farm use or sale in 2021 (p=0.00001), and whether the farmer reported that small grains cost shares or conservation incentive payments (e.g., EQIP or CSP) are available to them (p=0.0002). Whether a farmer reported that crop insurance for small grains is available in their county (p=0.011) is also associated with whether a farmer plants small grains. Each of these factors is positively associated with growing small grains, holding all other factors in the model constant. In other words, on average, farmers with operations that were certified organic, farmers with operations that had livestock, farmers who reported that cost share was available to them, and farmers who reported that crop insurance for small grains was available in their county are more likely to grow small grains.

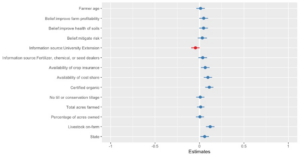

Beliefs as to the benefits of small grains and where farmers source their information regarding small grains are also important to decision making around growing small grains, although with comparatively weaker associations. If a farmer believed that small grains in rotations improve farm profitability or improve the health of soils, they are statistically more likely to grow them (significant at the 10% level). On the other hand, if a farmer considered University Extension personnel as a top information source regarding small grains, they are less likely to grow them (significant at the 10% level). This suggests that farmers who grow small grains are using other information sources besides Extension to meet their needs. A farmers age, whether they believed that small grains in rotations mitigates risk, whether they selected fertilizer, chemical, or seed dealers as a top information source regarding small grains, whether they use no-till or conservation tillage practices, their total acres farmed, and their percentage of acres owned vs rented were not associated with growing small grains. Figure 3 displays theses associations in terms of the odds that a farmer will grow small grains (listed on the x axis) depending on the factors listed on the y axis.

Table 1. Logistic regression predicting whether a farmer currently grows small grains

Figure 3. Visual display of factors associated with the likelihood of whether a farmer grows small grains

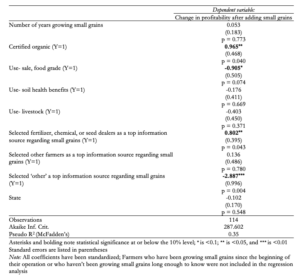

In addition to whether a farmer grows small grains, we tested what determines whether small grains are profitable in the operation (Table 3). The most important factor associated with profitability of the farming business as a whole after adding small grains to rotations is whether the farmer selected “other” as a top information source regarding small grains. Those who selected ‘other’ as a top information source regarding small grains were the most likely to report either very little change or an increase in their farm’s profitability compared to a decrease (p=0.004). The most common responses to other includes resources accessed independently such as farm magazines, research reports, and online articles (7), a farmer’s own experience through trial and error (5), and seed companies (3). Farmers with operations that were certified organic (p=0.040) and farmers who selected fertilizer, chemical, or seed dealers as a top information source regarding small grains (p=0.043) are also associated with greater profitability. Growing small grains for sale to food grade markets is associated with reduced profitability (p=0.074). The number of years growing small grains, growing small grains for their soil health benefits, whether an operation had livestock, farmers who selected other farmers as a top information source regarding small grains, and the state in which the farmer is located are not associated with profitability.

Table 2. Ordered logistic regression predicting greater profitability after adding small grains to rotations

Key drivers

Below we discuss in further detail several key determining factors of whether a farmer grows small grains and the factors determining profitability based on farmer-reported results and regression results. We include additional summary statistics and results from in-depth interviews and focus groups with farmers and actors throughout the grain chain to understand how and why these factors impact small grain production.

Economics

The most frequently listed barriers to growing small grains by all farmers in the sample (current, discontinued, and non-small grain farmers) were economic factors. Specifically, farmers reported the market price for small grains, the availability of small grain markets, and the distance to a buyer of small grains as the key barriers to integrating small grains on their operation, whether for sale or for on-farm use (Figures 1 & 2). Both organic and non-organic farmers echoed this finding during focus groups and interviews where there was a resounding sentiment that to grow more small grains, more local markets were needed with higher prices. An organic farmer from Minnesota summarized it as: “Price is the first factor; it’s always going to be the driving force behind those decisions.” Farmers explained that while small grains require fewer inputs, making them less expensive to raise, the return on investment of corn and soybeans is higher. Still, other farmers said that in order for them to plant more small grains, prices must be comparable to corn and soybeans. Loans for small grains production weren’t frequently listed as barriers, yet farmers told us that acquiring a loan requires a business that lenders see as profitable, making small grains less attractive compared to corn and soybeans.

Local buyers for small grains were also identified as lacking as farmers told us that their local elevators no longer buy small grains. An organic farmer from Minnesota recounted that he had to haul his wheat over 100 miles to find a buyer “because otherwise the local elevators won't even take it because it's a pain. Because they're all set up for corn and soybeans and where are you going to put put a truckload of wheat?” While organic farmers are used to trucking their produce farther to find specialty buyers, many farmers said that the distances required to haul their small grains was too far to make production economical. An organic small grains farmer from Illinois explained: “You know, I think if we're going to grow wheat, or we're going to grow barley, whatever we can grow, I think you're going to have to look at a transportation problem…I have to go somewhere at a distance to us. So that's a problem.” Several farmers we spoke with have had to sell their grains on conventional or livestock markets at a lesser price after failing to find local buyers for their organic grain. Overall, however, farmers felt that the demand for organic products, including small grains, is growing and they saw potential for future small grain markets. Farmers suggested that building consumer markets by launching and building brands for diverse products, supporting more local milling and processing, and developing farmer marketing coops are key to supporting small grain markets in the region.

Improved small grain varieties

Access to improved small grain varieties relevant to a farmer’s geographic region or desired markets was the third most selected factor that helped small grain farmer’s ability or willingness to grow small grains (Figure 1). Those farmers who have discontinued growing small grains and those who have never grown small grains did not commonly report a lack of improved small grain varieties as a barrier (Figure 2), although this may be due to non-small grain farmers inexperience with small grain varieties. Improved varieties can help farmers increase yields and manage disease and toxins from mold and fungi such as vomitoxin, fusarium, and aflatoxin that are particularly challenging in the Midwest due to higher levels of rainfall and humidity during the growing season.

During focus groups and interviews, the issue of genetics came up frequently and farmers told us that they did not have the small grain varieties, especially for organic production, that they need to be profitable. There was a particular focus on the need for varieties suited to the wetter conditions of the Midwest to compete with farmers in the Dakotas and Canada where much of the small grains are currently grown. An organic farmer from Illinois told us: “I think I think there's profit to be made (in small grains). We just need to be looking at different varieties…I'm not sure that we've really developed wheat, for our organic side, the problem with the organic side is that you have no rescue, you can't go in with fungicides, you can't go in with the herbicides, you can't go in with anything like that…I'd like to see maybe a little better, a little different breeding program. And I'm not sure that's ever going to happen, because I'm not sure that the money is going to be enough to be able to do that. That's the key. You know, it's a chicken and egg thing…(But) there needs to be some new characteristics in it. Some new varieties brought out. I mean, we're planting the same oats I did as a kid. You know, 45 years ago.”

During a focus group, several small grain breeders lamented that funding is lacking for public small grain breeding programs. They explained that more sustained, long-term funding from farmers through commodity association check off programs or the public sector is needed. Still, there was a sentiment amongst the breeders that hybrid varieties with chemical input packages tend to be seen as modern or cutting edge and therefore more desirable. Small grains, however, naturally require fewer inputs, in part due to their history in public breeding, and therefore more of the profit goes to the farmer compared to agrochemical companies. This results in a better outcome for farmers bottom lines as well as the natural environment. Promoting the low-cost and low-management nature of small grains can help re-orient farmers to their inherent benefits compared to corn and soybeans.

Organic certification

Farmers with operations that are organic or transitioning to organic were important to small grain adoption in both regression analyses (Table 1 & 2). Regression results show that farmers with operations that are certified organic are more likely to grow small grains and are more likely to observe increases in profitability. Small grains are a viable and common way to fulfill the extended crop rotation requirement for organic certification. Without the ability to spray chemical pesticides and fertilizers, organic farmers use small grains in extended rotations to help build fertility and manage pest naturally.

Still, organic farmers struggle to make a profit from their small grains. An organic farmer from Illinois said, “The corn and beans are very profitable, the small grains portion of the operation is where we struggle to make money…The profitability on the corn and beans is what supports the organic operation, the small grains is what we do pretty much because we are required to to have the three-crop rotation.” Making small grains more profitable by addressing the barriers and capitalizing on the drivers identified in this study can act as a gateway to organic certification: farmers will be more likely to commit to a third small grain crop in a rotation if they know it will be profitable.

Livestock

Regression results show that farmers with integrated crop-livestock operations are significantly more likely to grow small grains (Table 1). This is likely due to the synergies between small grain production and livestock: livestock in operations with small grains can help lower the risk of growing them by acting as a secondary market for grain that doesn’t find a buyer and as a source of feed and bedding. Regression results of the drivers of small grain profitability (Table 2) tell a similar story: farmers who sold for food grade production are more likely to see a reduction in the profitability of the farming operation after adding small grains compared to those who don’t grow for food grade production.

Food grade production of small grains in the Midwest is risky due to the difficulties of meeting quality grade specifications required for milling and malting. A much higher percent of farmers in the study (70%) grew small grains for livestock, either for on-farm feed or bedding, sale as feed, or sale as straw compared to those who grew for food or beverage grade (38%). During focus groups and interviews farmers discussed the trouble competing with regions of lower humidity and rainfall that have fewer issues meeting standards of moisture content, falling numbers, and test weights. Because of these issues, farmers were often paid less than they expected for their small grains due to quality discounts, making their production a less reliable source of income compared to corn and soybeans, a risk that was often not worth the reward given their low market prices.

Livestock markets, on the other hand, have fewer quality requirements and several farmers stated that livestock feed and bedding are the most viable markets in the region. Many of them said that they would be more likely to grow more small grains if they had livestock markets around them or livestock on-farm. A small grains farmer from Illinois said that livestock is “our big limitation, not just for markets, but to have fertilizer, we are trucking chicken litter down from Michigan and it’s not only high price, but we are trying to reduce carbon footprint and running a semi that round trip is not helpful.” Livestock in many areas, however, has dwindled as crop and livestock systems have decoupled and livestock production has concentrated in certain areas. Re-integrating crop and livestock production throughout the region will be key to encouraging local markets for small grains and to encourage small grain production for on-farm use. Yet, even in areas concentrated with livestock, markets for small grains as feed are few and they are seen as slower to fatten the animal compared to corn and soybeans, and less palpable to the animal. Mandated small grain requirements in livestock rations and greater varietal development for small grain varieties suitable to livestock feed can help improve their potential as livestock feed.

Soil health benefits

While growing small grains for soil health benefits was not associated with profitability (Table 2), if a farmer believed that small in rotations improve the health of soils, they are more likely to grow them (Table 1). While it is clear that economics is central to whether a farmer grows small grains (Figures 1 & 2), and that farmers struggle to make small grains profitable, many farmers in focus groups and interviews said they continue to grow them “on principle” due to their soil health benefits. One farmer from Iowa explained that it is part of his “conservation ethic” to ensure the health of his soils and local waterways.

Farmers we surveyed recognized the soil health benefits of small grains—46% grew small grains at least in part as a cover crop or green manure, 59% said that the reason why they grew small grains was in part due to the soil health benefits (the most selected reason), and 65% of respondents said that they believed small grains in rotations improve the health of soils. One organic farmer from Illinois said: “I have noticed that when I took this farm over seven years ago, they were not doing hardly any small grains. And I have, you know, really stepped in to do it. And I find, I mean, we're doing less tillage. So, you know, especially in today's market and the price of fuel, everything that's got small grains on it, that soil seems to be much, much looser, a much nicer soil, better seed beds. So, I think we're gaining on the corn and soybean end of it also, gaining some production here.”

Thus, while stronger markets for small grains will do the most to incentivize their use, promoting their conservation benefits may also drive production, in particular on marginal land. Research shows that these soil health benefits result in increases in corn and soybean yields and increases to the combined net return of the rotation (Davis et al. 2012; Gaudin, Tolhurst, et al. 2015; Hunt, Hill, and Liebman 2019; Bowles et al. 2020; Janovicek et al. 2021). One farmer from Iowa suggested that growing small grains as a cover crop or in a cover crop mix can act as a gateway to incorporating a small grain as a third crop in a rotation. Once a farmer sees the soil health benefits of the cover crop, they will be more comfortable putting a small grain crop in a rotation. Given that using small grains as a cover crop is the most common single use for grains listed by farmers on the survey, this may be a promising strategy to diversifying rotations through small grains.

Cost share programs

Farmers did not commonly report that cost share programs such as EQIP or CSP influenced their decision making (Figures 1 & 2), however, regression analysis showed that farmers who said that cost share for small grains was available to them were significantly more likely to grow them, controlling for other variables in the model (Table 1). While many farmers weren’t aware whether cost share was available (26% of the sample), those small grain farmers who said they were available participated widely—74% used a cost share program. The most commonly used incentive program was EQIP, used by 47% of small grain farmers in the sample, compared to CSP, a nongovernmental source such as Practical Farmers of Iowa, or other programs.

Of the small grain farmers who did not participate, the most common reason why was that they were not interested in financial assistance. That the qualification criteria were unclear, and the paperwork involved in the application excessive were also frequently selected. This was also a resounding sentiment during focus groups and interviews where farmers felt overwhelmed with the amount of documentation and hoops needed to go through to participate. An organic farmer from Minnesota said: “It always seems like there is so much documentation and you have to go through so many hoops to do something simple, it always seems overwhelming when you sign up for a program.” Another farmer commented on the survey that more flexibility in the programs was needed: “The timing of the cost share rounds do not line up well with planning and do not allow for much flexibility. Sometimes a field will be too wet after we sign up and we need to switch fields or sometimes we don't yet know which field we want to plant the small grains on. We wish there was more flexibility in the programs. Sometimes we plant the small grains and then it's too late to sign up for the programs because it's a practice we already did, simply because the timing didn't line up.”

Other issues farmers through to light in focus groups and interviews were that for EQIP and CSP, small grains can only be used as a cover crop, prohibiting farmers from harvesting the grain. Moreover, an herbicide must be applied to kill the small grains before planting, making its use difficult for organic farmers. Still other farmers said that they would like to participate, however funds weren’t available, and the programs had reached capacity in their area.

Cost share programs will be more effective for farmers if the application processes are simplified, and greater flexibility is afforded to participants. To realize the potential of cost share on adoption, more funding is needed to support the programs, especially given their strong association with whether a farmer plants small grains. The fact that 77% of non-small grains farmers said that they did not know whether cost share for small grains was available to them suggests that it may be a missed opportunity to promote the use of small grains. More outreach to farmers about cost share and other incentive payments for small grains is needed, particularly non-small grain farmers that may be incentivized to begin testing small grains in rotations.

Crop insurance

Crop insurance was not commonly reported by farmers to influence their decision whether to grow small grains (Figures 1 & 2). This was re-iterated during focus groups and interviews where farmers told us that they don’t make decisions based on insurance but based on what there is a market for. An organic farmer from Illinois said in response to whether better crop insurance policies would make a difference in his choices: “I don’t think we would change our decisions. Even though the small grain portion of what we do is more difficult, we have struggled along and made it work. We’ve never had, other than the barley, a complete disaster growing wheat or oats.”

While crop insurance for small grains is not central to farmer decision making, like many of the non-economic factors we analyzed, it is still a driver of production. Regression analysis revealed that farmers who said that crop insurance was available in their county for some or all of their small grains were more likely to grow them, on average, compared to those who said they did not know or said that it was not available in their county (Table 1). Survey data also shows that 49% of farmers said that they did not know whether crop insurance was available for small grains in their county. It is likely that farmers are not aware of crop insurance because it is less important to them in their decision making compared to economic factors, and therefore they have not taken the time to investigate it. However, the lack of awareness may also be explained by the failings of the current state of crop insurance for small grains.

Through focus groups and interviews with farmers and crop insurance agents, it became clear that there are several issues that make crop insurance for small grains less valuable compared to crop insurance for corn and soybeans. Farmers explained that crop insurance for small grains was too cumbersome, too complicated, and not worth the value offered. Farmers beginning to grow small grains lack the three-year yield history needed to determine the price guarantee. Established base yields at the county level can be used in lieu of yield history, however farmers pointed out that the yield was often lower than what they expected on their own operation. Moreover, since they are no longer commonly grown in the region, few counties have established base yields for small grains, and the farmers must make a request to use yield data from other counties.

Crop insurance is further complicated for organic growers who must take the premiums and payouts based on conventional prices that are not reflective of their organic premiums. Likewise, the value insured does not always reflect higher prices for food grade production compared to feed grade, or for more lucrative small grain varieties. In addition, crop insurance is not available in many counties for all small grains such as rye and kernza® and cannot be used when double cropped with corn or soybeans.

Whole Farm Revenue Protection is a program that aims to provide insurance coverage for diversified systems and could make it easier to insure operations that grow small grains in diverse rotations. Yet, only 8% of farmers in the study used whole farm revenue insurance for their small grains, and most of those reported that the program was complicated to enroll in and must be streamlined for more farmers to use it.

These findings suggest that subsidized crop insurance for small grains is a missed opportunity for supporting production and that insurance policies for small grains need to be adjusted to make them worthwhile for farmers. More educational outreach regarding crop insurance for small grains is needed, especially to non-small grain farmers, to encourage adoption through this risk reducing policy mechanism. Moreover, more robust coverage, especially for less common small grains, will also be important to maximize the benefits of crop insurance for diversification.

Conclusion

Small grains are one of the easiest ways that corn and soybean farmers can diversify as they fit well into a large-scale row crop systems and provide agronomic and environmental benefits. A growing body of evidence shows that diversified crop rotations that include small grains can improve yield and profitability while enhancing soil health and water quality (Bowles et al., 2020; Davis et al., 2012; Hunt et al., 2019). Yet, despite their benefits and emerging economic promise, most farmers do not plant small grains. Barley, oats, and rye have seen steady declines in acreage in Midwestern states over the last century according to data from USDA. At the same time, corn and soybean acreage has grown dramatically (USDA 2020). Small grains currently constitute less than 4% of total field crop acres planted in the region (USDA 2017).

There are a myriad of interconnected reasons why farmers in the Midwest primarily plant only one to two crops and why diversifying to additional crops, in particular small grains, is difficult. Farmers identified economics as being the most important, yet markets and prices are supported by strong genetics that produce high yielding and pest resistant crops, policies that minimize risk, infrastructure that provides cleaning and processing, and production techniques that reduce labor and maximize efficiency. Over the last 70 years of agricultural industrialization, we have made it easier economically and agronomically to grow corn and soybeans, and subsequently harder to grow other crops, even those that were once as common in rotations as small grains. Each of the factors that went into making corn and soybeans easier to grow must be considered when understanding the drivers of the current system. To level-the playing field for small grains, it is clear that more robust markets are necessary. However, “you can’t build the market without the product” as one organic grower from Wisconsin said. The factors that enable strong agricultural markets and can support farmers to produce small grains including organic production, integration of crop and livestock production, crop research and development, processing infrastructure, federal crop subsidies, and supply mandates such as the Renewable Fuel Standard will all play a role. Each must be addressed to ensure that small grains have the same market potential as corn and soybeans in the Midwest.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation Summary:

I plan to submit a paper to the Journal of Rural Studies spring of 2023 with the findings of this study. I am hoping to present, along with the collaborators in the study, this research at the 2023 Marbleseed conference, and the 2023 Soil and Water Conservation Society conference. I am currently working with the University of Wisconsin Organic Grain Research and Information Network (OGRAIN) to create a small grains marketing FAQ sheet. The results of this work will be featured in the Michael Fields Agricultural Institute and Artisan Grain Collaborative newsletters.

Project Outcomes

Understanding the barriers and opportunities to planting small grains in diverse crop rotations enables decision makers in agriculture to take needed steps to improve the policies, investments, and technical support around small grain production. To ensure this research reaches these decision makers, we plan to disseminate a comprehensive report of findings and recommendations, accessible fact sheets, articles, and policy briefs for distribution both during the project period and following. The partners included on this research will share findings and recommendations for structural change to leaders of relevant federal agencies (e.g., RMA, FSA, Extension), state agency or policy leaders, market leaders, agricultural lending leaders, policy-engaged NGOs, statewide agricultural education leaders, and farm groups in the region. When steps are taken to address the barriers and opportunities identified in our findings, it will be easier for farmers to add small grains to their rotations and to benefit from the improved profitability and ecological health small grains provide while helping to build resilient local food systems.

Environmental: A growing body of evidence shows that diversified crop rotations that include small grains and forage crops can improve yield and profitability while enhancing soil health and water quality. Diversifying rotations naturally disrupts cycles of weeds, pests and diseases, ultimately reducing farmers’ use of pesticides and herbicides (Rosenzweig et al., 2018). And as cool season crops, small grains increase surface cover and roots in the ground year-round, improving water, nutrient and sediment retention. This, in turn, reduces nitrogen and phosphorus runoff and freshwater toxicity (Hunt et al., 2019). Diversified rotations have also been shown to improve soil health factors, including soil structure and microbial diversity (Singh, 2020).

Economic: Beyond improved ecological and agronomic conditions, small grains grown within rotations can be valuable additional sources of income and help farmers diversify risk (Liebman et al., 2008). With more than a decade of volatile commodity prices for corn and soybeans, the reintegration of small grains into Midwestern landscapes can improve the economic viability of farms by offering alternate markets, including the potential to sell organic crops to local or regional high-value food-grade end-users. Moreover, prices of inputs are lower and yields higher in extended rotations which include small grains, due to natural disruption of pest cycles and regeneration of soil organic matter.

Social: The local production of small grains benefits communities in the form of fresh local grain supplies and unique varieties for a more diverse and nutritious diet, in addition to fueling the operations of local brewers, distillers, bakers, chefs, and food manufacturers in search of high-quality organic grains. Growing markets for food-grade organic small grains can help create value-added agricultural products that keep more money circulating in local economies.

I gained a great deal of knowledge about the myriad of interconnecting reasons that make it worthwhile, at present, to farm corn and soybeans and the challenges farmers face to diversify. It is easy to conclude that there is one loose cog in the wheel that makes it difficult for farmers to diversify from corn and soybeans and into crops like small grains, whether it be markets, policies, infrastructure, research and development, or simply the ease of the corn and soybean system. However, the reality is that what drives a farmer’s decision of whether to diversify their production system to include small grains is a complex and interwoven web of factors that cross economics, politics, personal values, geography, climate, and material needs such as improved genetics and local processing. Disentangling the web, I have realized, requires knowledge of the history of agriculture in the region, an understanding of farming culture, and a keen sense of how each factor listed above plays off another.

Small grain farmer, Iowa: "(Change is) Not going to happen overnight, but it takes someone willing to start gathering information and doing research and be willing to listen and talk about pros and cons, that's where solutions are going to start from.”

Corn and soybean farmer, Wisconsin: “A questionnaire does not capture it because there are a million things you don't think about when you're filling out that questionnaire. But when you have a couple of people talking, and you hear something and go 'oh yea' and that triggers a thought you had, and I think it's much better to have these discussions as opposed to just filling out a questionnaire. To me it's a benefit, I'll take an hour out of my day because it hopefully helps down the road.”

I believe it will be important to assess farmer attitudes towards more dramatic changes to farm policy than this work was able to assess including removing or re-shaping biofuel mandates in ethanol production and making substantial changes federally subsidized crop insurance to subsidize lower risk and regenerative farming practices. Farmers in this study also told us that more research on the economic value of small grains in corn and soybean rotations (dollar per acre benefit) would help them in their decision whether to extend their rotations to include them.