Final report for GNE15-108

Project Information

Double cropping has the potential to increase on-farm forage production as well as provide environmental benefits such as rotation diversity, erosion control, end-of-season nutrient uptake, and increased soil organic matter. With NESARE funding, the ideal N application rates are being evaluated for triticale and cereal rye, two winter cereals well suited to the northeastern United States. Farmers have stated that these winter cereals grown as double crops harvested at the flag leaf or boot stage have resulted in increased milk yield in dairy cattle. Basic quality assessments conducted to date show an increase in crude protein with addition of N and decline in overall quality with delay in harvest but these findings do not explain an increase in milk production when the forage is harvested at the optimal timing. This increased milk potential of winter cereals may be partly due to an increase in digestibility of the diet when winter cereals are included. Through in vitro analyses of triticale and cereal rye, this study aims to determine in more detail the digestibility (and milk production potential) of the winter cereals grown at various N rates (0 to 120 lbs N/acre). Additionally, for a subset of samples quality parameters of dry forages are compared to that of ensiled forages. The Cornell Net Carbohydrate and Protein System (CNCPS) is also used to evaluate the ensiled samples and their performance in a typical NY dairy total mixed ration (TMR). Further, a survey was developed to be distributed to farmers, farm advisors, and nutritionists who have experience with double cropping to get a better idea of how farmers are currently growing, processing, and/or feeding double crops in the Northeast. A better understanding of the milk producing potential of winter forages will help farmers make more informed decisions about implementing double crop rotations.

Introduction:

Increasing on-farm forage production in the northeastern US, where dairy operations produce most of their forage resources on the farm (Cook et al., 2010), could add to greater whole-farm nutrient use efficiency and improve farm economics. Double cropping, or growing two harvestable crops within one growing season, can increase yields by 2 tons/acre or more (Heggenstaller et al., 2009; Ketterings et al., 2015; Long et al., 2013b). Double cropping systems also provide the environmental benefits of cover crops, such as soil conservation, reduced erosion, nitrate leaching, and phosphorus runoff, and soil carbon addition by roots (Brandi-Dohrn, 1997; Gabriel et al., 2013b; Long et al., 2013a), and help with forage production risk management. As one New York farmer stated, “The double-cropped winter triticale is a great risk management tool. The more diversity of crops you have, the better you can handle the variations in weather during the growing season.”

Anecdotal farmer experience with feeding of winter forages shows that cows produce more milk when fed high quality winter forages than expected using standard forage quality indicators. As stated by another farmer about triticale: “It’s here to stay. It’s fed at 50% of the haylage dry matter of the ration from the end of May until the inventory runs out. The cows perform well on it and the herd managers are happy with incorporating it into the feeding program.” Yet, little is known about what management aspects impact the digestibility of these winter cereals, and how to best manage for high yields and quality. Results to date confirm that delaying forage harvest results in increased yields but at the expense of feed quality, consistent with work by Heggenstaller et al. (2009) and Cherney and Marten (1982). Forage yield and quality can both impact the economic return on investment of growing double crops in corn silage or sorghum rotations. It is thus not surprising that farmers identified the need for better understanding of forage quality as a high priority (Ketterings et al., 2015). Here we propose to evaluate forage digestibility (in vitro at 48 hr) as impacted by fertility and harvest management. Our hypothesis is that the elevated milk production potential of winter cereals as talked about by farmers is due to greater digestibility, if the winter forages are harvested in time and managed with optimum soil fertility.

Literature Cited:

- Brandi-Dohrn, F.M., R.P. Dick, M. Hess, S.M. Kauffman, D.D. Hemphill, J.S. Selker. (1997). Nitrate leaching under a cereal rye cover crop. J Environ Qual 26(1):181.

- Cherney, J., G. Marten. (1982). Small grain crop forage potential: I. Biological and chemical determinants of quality and yield. Crop Sci 22:227-231.

- Cook, A.L., P.S. Heacock, G.S. Criner, and L.A. Bragg. (2010). Organic milk production in Maine: Attributes, costs, and returns. Tech Bull 204. Maine Agric Exp Stn, Univ. of Maine, Orona, ME.

- Gabriel, J.L., A. Garrido, M. Quemada. (2013). Cover crops effect on farm benefits and nitrate leaching: Linking economic and environmental analysis. Agr Syst 121:23-32.

- Harmoney, K.R., C.A. Thompson. (2005). Fertilizer rate and placement alters triticale forage yield and quality. Forage and Grazinglands. doi: 10.1094/FG-2005-0512-01-RS.

- Heggenstaller, A.H., M. Liebman, R.P. Anex. (2009). Growth analysis of biomass production in sole-crop and double-crop corn systems. Crop Sci 49:2215.

- Ketterings, Q.M., T. Kilcer, S. Ort, and K.J. Czymmek. (2013). Double cropping winter cereals yields triple bottom line. Eastern Dairy Business; The Manager. 5(2):15-16.

- Ketterings, Q.M., S. Ort, S.N. Swink, G. Godwin, T. Kilcer, J. Miller, W. Verbeten. (2015). Winter cereals as double crops in corn rotations on New York dairy farms. J Agri Sci 7(2) doi: 10.5539/jas.v7n2p18.

- Long, E., Q.M. Ketterings, K.J. Czymmek. (2013a). Survey of cover crop use on New York dairy farms. Crop Management. doi: 10.1094/CM-2013-0019-RS.

- Long, E., K. Van Slyke, Q.M. Ketterings, G. Godwin, and K.J. Czymmek. (2013b). Triticale as a cover and double crop on a New York dairy. What’s Cropping Up? 23(1):3-5.

- Murdock, W.L., and K.L. Wells. (1978). Yields, nutrient removal, and nutrient concentrations of double-cropped corn and small grain silage. Agron J 70:573-576.

- SAS Institute. 1999. SAS/STAT user’s guide. Release 8.00. SAS Inst., Cary, NC.

- Schwarte, A.J., L.R. Gibson, D.L. Karlen, M. Liebman, and J. Jannink. (2005). Planting date effects on winter triticale dry matter and nitrogen assimilation. Agron J 97:1333-1341.

The objectives of this study are to

- Compare the nutritive quality via digestibility analysis of two species of winter cereals (triticale and cereal rye) grown at differing N rates. In vitro digestibility analysis as well as analysis for crude protein (CP), neutral detergent fiber (NDF), and ash content was performed on forage samples for two cereal rye fields in eastern NY and four triticale fields in central NY (2015), each with multiple N rates applied. Forage samples from two additional triticale N rate trials in central NY (spring 2016 and 2017) included in a double cropping rotation study were also analyzed. Objective was completed by fall 2017.

- Determine the quality effects of ensiling the two species of winter cereals. The 2015 and 2016 forage samples were also ensiled for 30 days starting at time of harvest and were analyzed for quality. Quality results were entered into CNCPS at different percentages substituting either corn or alfalfa haylage to observe their performance in a dairy TMR. Objective was completed by fall 2016.

- Evaluate the economic advantages of double cropping from a farm feed nutrient requirement and milk production perspective. A survey was developed and tested with the help of a nutritionist and the survey will be distributed more widely at upcoming winter meetings. Objective completed by fall 2017.

Cooperators

- (Researcher)

Research

Field trials: Forage samples were collected from 7 on-farm winter cereal trials in 2015 and 2016 as well as from a larger rotation study in 2016-2017. The on-farm trials included two cereal rye and 5 triticale N rate trials. Each trial had 5 rates of N applied at green-up in the spring (April 15 for the 2015 cereal rye trials and the 2016 triticale trial, and April 16 for the 2015 triticale trials) hand-applied with AGROTAIN-treated urea (0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 lbs N/acre) in 10 ft x 10 ft plots in 4 replications. Plots were hand-harvested at flag-leaf stage in May of each year, yield was measured, and forages were prepared for quality analysis. Yield information was used to determine the most economic rate of N (MERN) for each trial as part of NESARE project “Winter triticale or rye as a double crop to protect the environment and increase yield” (LNE14-332). Subsamples from these seven trials were ensiled by placing forage in food-grade vacuum sealed bags with a homolactic bacterial inoculant post-harvest and fermented for 30 days.

The rotation trial in 2016-2017 had both an N rate and a timing of planting component. Triticale was planted at four timings in the fall (early, mid, and late September and early October) following forage sorghum silage harvest. Five rates of N of AGROTAIN®ULTRA-treated urea (Koch Agronomic Services, LLC, Wichita, KS) (0, 30, 60, 90 120 lbs N/acre) were applied at green-up in the spring. In addition, the forage sorghum preceding the triticale had two rates of N applied at planting (0 and 200 lbs N/acre), dividing the triticale plots in half to accommodate for any carryover. All triticale plots (n = 160) were harvested at flag-leaf stage in May for yield assessment, and subsamples were collected and prepared for quality analysis.

Forage quality analyses: All forage samples (either at harvest or after ensiling) were dried at 122°F and ground to 1 mm with a Wiley mill. All ensiled samples were submitted to Cumberland Valley Analytical for quality analysis (NIR) for use with CNCPS evaluations. Freshly dried samples were submitted to Brookside Laboratories for total N content and analyzed for in vitro digestibility and fiber content at the Forage Laboratory of Dr. Cherney at Cornell University. Statistical analyses were performed with PROC MIXED of SAS (SAS Institute, 1999).

Ration formulations: With the help of Sam Fessenden, then Ph.D. student in the research laboratory of Dr Van Amburgh, quality results from the ensiled samples were assessed for ration performance using CNCPS, by substituting for either corn silage or alfalfa silage at different percentages (0, 25, 50, 75, or 100% of corn silage and 0, 50, or 100% for alfalfa silage; Table 1). The theoretical ration and animal information is detailed in Table 1 below. Simulation results involving diet and milk performance were compared to the control (0% substitution).

Farmer and nutritionist survey: Two surveys, one for nutritionists and one for producers, including questions on farm characteristics, winter cereal production information, details on experience with feeding winter cereals and animal performance, and perception of growing winter cereals for forage, were developed. An extensive list of interested participants generated by extension agents, nutritionists, faculty, and direct communication with producers was prepared to capture a wide range of winter cereal forage production experiences. The survey has been submitted for review and will be distributed once approved.

Table 1. Animal information and baseline ration inputs used for determining performance of winter cereals in a typical dairy total mixed ration (TMR) in New York using the Cornell Net Carbohydrate and Protein System (CNCPS) version 6.55. Winter cereals (triticale, cereal rye) were substituted for either corn silage or alfalfa silage.

|

Animal information |

Base ration inputs (% of diet) |

||

|

Milk production (lbs/day) |

88 |

Corn silage (30% DM) |

38.5 |

|

Milk fat (%) |

3.75 |

Alfalfa silage (20% CP) |

17.3 |

|

Milk true protein (%) |

3.1 |

Corn grain ground fine |

17.3 |

|

Age of first calving (months) |

22 |

Soybean meal |

5.8 |

|

Mature weight (lbs) |

1,653 |

Soybean hulls, pellet |

5.8 |

|

Age (months) |

65 |

Cottonseed, fuzzy |

3.8 |

|

Age of first calving (months) |

22 |

Soy plus |

3.8 |

|

Current bodyweight (lbs) |

1,653 |

Citrus pulp, dry |

1.9 |

|

Days since calving |

120 |

Corn gluten feed, dry |

1.9 |

|

Condition score |

3 |

Blood meal, average |

0.8 |

|

Ambient temperature (°F) |

68 |

MinVit |

2.7 |

|

|

|

Trace mineral premix |

0.4 |

Winter cereal yield and quality: Two of the seven N rate trials had MERNs of 0 lbs N/acre (no additional N required for optimal yield), while the remaining five had MERNs ranging from 20-90 lbs N/acre, averaging 53 lbs N/acre. Yields at the MERN ranged from 0.7 to 3.1 tons DM/acre with an average of 1.5 tons DM/acre.

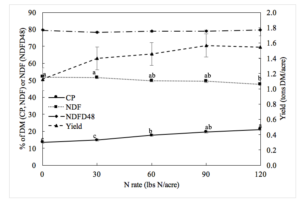

All N rate trials had increased CP when N was applied regardless of the MERN. Across trials, CP increased up to the 90 lbs N/acre treatment (Fig. 1). The only other quality parameter that changed with N application was NDF, which had a slightly lower value at higher N rates. The NDF digestibility (48 hour digestion; NDFD48) was not affected by N rate. Forage CP at the MERN ranged from 10-21% of DM and NDF at MERN ranged from 47-55% of DM (Table 2). Because NDFD48 was not impacted by N rate, NDFD48 at the MERN was equal to the average NDFD48 across all N rates, which ranged from 76-84% of NDF.

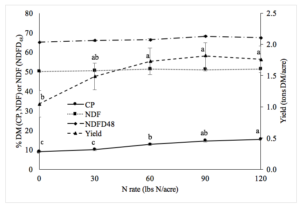

For the rotation trial, the MERN was 76 lbs N/acre with a yield at the MERN of 1.8 tons DM/acre, similar to findings in the individual N rate trials. Forage CP at the MERN was 13% of DM, NDF at the MERN was 51% of DM, and NDFD48 was 67% of NDF (Table 2). As with the N rate trials, in the rotation study that forage CP increased with additional N applied while NDF and NDFD48 remained constant over all N rates (Figure 2).

Nitrogen management of winter cereals for forage is important for acquiring both optimal yield and crude protein (fiber and digestibility are not as sensitive to N application). Even if the MERN is 0 lbs N/acre, as it was for 2 of the N rate trials, not applying N in the spring could impact forage CP. In some cases, farmers may choose to supplement alfalfa or alfalfa/grass silage with forage winter cereals in TMRs, so dietary protein is an important consideration when making fertilizer management decisions.

Table 2. Most economic rate of N (MERN), yield at the MERN, and quality at the MERN for 7 winter cereal N rate trials and a double crop rotation trial in New York.

|

Trial ID |

MERN |

Yield at MERN |

CP at MERN |

NDF at MERN |

NDFD48 at MERN |

|

|

lbs N/acre |

tons DM/acre |

% DM |

% DM |

% NDF |

|

1 |

51 |

1.5 |

17 |

55 |

77 |

|

2 |

51 |

1.0 |

16 |

55 |

77 |

|

3 |

53 |

1.4 |

16 |

53 |

79 |

|

4 |

0 |

1.3 |

21 |

49 |

80 |

|

5 |

90 |

1.4 |

16 |

48 |

79 |

|

6 |

20 |

0.7 |

17 |

47 |

84 |

|

7 |

0 |

3.1 |

10 |

47 |

76 |

|

Rotation |

76 |

1.8 |

13 |

51 |

67 |

Ensiling and winter cereal quality: Ensiled samples were different from the freshly dried samples for most forage quality parameters. Across all N rates, ensiled samples had significantly higher CP, lower NDF, higher lignin, and lower NDFD. However, TDN was not different between the two post-harvest methods (Table 3). These findings have implications for in-field estimation of forage quality, as many forage samples are analyzed for quality before ensiling occurs. These changes are important to consider when balancing rations so that they adequately represent the nutrients that the animal would receive, and point to the importance of analyzing feed quality close to feeding.

Table 3. Quality parameters of ensiled and dried fresh samples for seven winter cereal N rate trials in New York.

|

Quality parameter |

Ensiled |

Fresh |

|

CP (%DM) |

19* |

18 |

|

NDF (%DM) |

47* |

50 |

|

Lignin (%DM) |

4.1* |

3.5 |

|

NDFD30 (% NDF) |

68* |

72 |

|

TDN (%DM) |

66 |

66 |

*Significantly different from the fresh sample quality. CP = crude protein; NDF = neutral detergent fiber; NDFD30 = NDF digestibility at 30 hr fermentation; TDN = total digestible nutrients.

Performance of winter cereals in TMRs: When winter cereals were substituted for either corn silage or alfalfa silage, there were some differences in milk performance and overall diet composition. Metabolizable protein (MP) allowable milk, MP supply, and diet CP were all influenced by both level of substitution and the N rate applied to the winter cereals, while metabolizable energy (ME) allowable, milk, ME supply, and diet ME were only impacted by level of substitution (Table 4 and Figure 3). Substituting winter cereals for 100% of the corn silage resulted in the greatest decrease in both ME and MP allowable milk, likely due to the lack of starch in the immature winter cereals. Substituting the forage winter cereals for 50% of the alfalfa silage was most similar to the control diet.

Table 4. Results from a ration simulation using CNCPS. Forage winter cereals grown at 5 N rates were substituted at 0%, 50%, and 100% of alfalfa haylage or corn silage in a typical dairy TMR. Different letters represent significant differences. Parameters with no letters indicate no significant differences between treatments.

|

Substitution |

N rate (lbs N/acre) |

ME milk (lbs) |

MP milk (lbs) |

ME supply (Mcal) |

MP supply (kg) |

Diet ME (Mcal/lb) |

Diet CP (% DM) |

|

|

----------------Forage winter cereals substituted for alfalfa silage---------------------- |

||||||

|

Control (0%) |

|

90.68 |

94.15 |

65.43 |

2.88 |

2.52 |

15.95 |

|

50% |

0 |

90.88 |

92.06 bc |

65.50 |

2.83 c |

2.52 |

15.75 c |

|

|

30 |

90.82 |

91.84 c |

65.46 |

2.83 c |

2.52 |

15.73 c |

|

|

60 |

91.14 |

92.61 abc |

65.66 |

2.84 bc |

2.53 |

15.98 b |

|

|

90 |

91.24 |

92.85 ab |

65.73 |

2.84 ab |

2.53 |

16.05 ab |

|

|

120 |

91.31 |

93.24 a |

65.79 |

2.85 a |

2.53 |

16.28 a |

|

100% |

0 |

91.05 |

89.99 bc |

65.57 |

2.78 c |

2.52 |

15.55 c |

|

|

30 |

90.91 |

89.53 c |

65.49 |

2.78 c |

2.52 |

15.52 c |

|

|

60 |

91.54 |

91.08 abc |

65.90 |

2.80 bc |

2.53 |

16.02 b |

|

|

90 |

91.74 |

91.58 ab |

66.03 |

2.81 ab |

2.54 |

16.16 ab |

|

|

120 |

91.87 |

92.34 a |

66.16 |

2.82 a |

2.54 |

16.41 a |

|

|

-----------------Forage winter cereals substituted for corn silage----------------------- |

||||||

|

50% |

0 |

84.53 |

89.64 bc |

63.18 |

2.81 bc |

2.43 |

17.82 b |

|

|

30 |

84.46 |

89.24 c |

63.17 |

2.80 c |

2.43 |

17.56 b |

|

|

60 |

85.00 |

90.91 abc |

63.55 |

2.82 abc |

2.44 |

18.33 a |

|

|

90 |

85.22 |

91.48 ab |

63.69 |

2.83 ab |

2.45 |

18.49 a |

|

|

120 |

85.37 |

92.34 a |

63.84 |

2.85 a |

2.46 |

18.77 a |

|

100% |

0 |

78.10 |

86.00 b |

60.93 |

2.76 bc |

2.34 |

19.69 b |

|

|

30 |

77.93 |

85.26 b |

60.92 |

2.84 c |

2.34 |

19.17 b |

|

|

60 |

79.15 |

88.71 ab |

61.67 |

2.74 abc |

2.37 |

20.72 a |

|

|

90 |

79.61 |

89.91 a |

61.96 |

2.79 ab |

2.38 |

21.03 a |

|

|

120 |

79.93 |

91.70 a |

62.25 |

2.81 a |

2.39 |

21.59 a |

|

|

|

||||||

This project has enhanced knowledge about growing winter cereals for forage and how they behave in typical dairy rations in the Northeast. Increased awareness about forage winter cereals have been presented and discussed through direct communication with farmers and extension agents, national and local meetings, and field days. From the N rate trials and the rotation trial, it is clear that N management is important for optimizing both yield and quality. While fiber components do not differ drastically with N management, forage CP is heavily influenced by fertilization and for many locations, crop yields respond to N addition as well. Additionally, most quality parameters shift after ensiling, which is another important consideration when deciding when to analyze forage for quality. When a typical dairy TMR had corn silage or alfalfa silage replaced with winter cereals using a ration balancing software, replacing 50% of the alfalfa silage with a winter cereal had the smallest impact on ration performance. Replacing 100% of the corn caused a large decrease in ME allowable milk, suggesting that an energy supplement would be necessary to bring up energy requirements in the diet. Based on discussions with nutritionists who work with New York dairy farmers, interest in growing winter cereals for forage is growing, emphasizing the need for management recommendations. This project adds to the evidence winter cereals can be nutritionally sound additions to dairy forage rotations in NY.

Education & outreach activities and participation summary

Participation summary:

We presented research on growing winter cereals at many different events, including extension talks, academic meetings, and research farm field days. We have gotten valuable feedback from farmers, extension educators, and university researchers, and enthusiasm about the findings has been apparent. We have recently published a factsheet explaining forage quality parameters as well as a What's Cropping Up? article on fall growth and N uptake of winter cereals. We are currently working on publications and fact sheets describing the feeding of winter cereals in dairy rations and plan to present these findings in meetings next year.

Certified Crop Advisor Training 2016

Cornell Nutrition Conference Presentation 2016

Certified Crop Advisor Training 2015

Planting date and N availability impact fall N uptake of triticale

Project Outcomes

Economic Analysis: While this project does not quantify economic gains or losses on farms who grow winter cereals for forage, the opportunity to grow a second crop within a growing season is intriguing and has the potential to be economically beneficial. Having a second crop for forage could provide an emergency crop during extreme weather events, secure leftover nutrients and possibly reduce imported fertilizer, and increase overall per acre yield. An economic analysis by Hanchar and others (Double cropping winter cereals for forage following corn silage: Costs of production and expected changes in profit for New York dairy farms) showed that in most cases it can be profitable to grow winter forages in rotation with corn silage even if fertilizer is purchased or corn silage yields are slightly reduced. Curtis Martin participated in the larger N rate study (Grant # LNE14-332) and said “After seeing the study results here, I'm changing the spring N rate on triticale from the 30 lbs/acre I had been applying to about 50 lbs/acre to get higher protein forage for the dairy herd. The cost of N makes it worthwhile for the feed quality benefit.”

Hanchar, J.J., Q.M. Ketterings, T. Kilcer, J. Miller, K. O’Neil, M. Hunter, B. Verbeten, S.N. Swink, and K.J. Czymmek. 2015. Double cropping winter cereals for forage following corn silage: Costs of production and expected changes in profit for New York dairy farms. What’s Cropping Up?

Farmer Adoption: Based on interaction with farmers at workshops as well as discussions with local nutritionists, many producers are either already double cropping with winter cereals for forage or are interested in learning how they might implement them on their farms. Curtis Martin stated: “Double cropping with winter triticale is great for my feed program and fits in beautifully with short rotations that keep soil covered to help my farm stay productive into the future.” Kevin Ganoe, a collaborative extension field crop specialist, said that “Flexible crop management such as John applies is part of the increased adoption of double-cropping. Farmers have gained awareness of soil health, so more acres across the region are covered in winter grains. I think it started with nutrient management plan requirements, and evolved into a realization that winter grain cover crops can make very good feed or straw. As double crops, they’ve become the third crop that fits into corn-hay rotations.” All farmers involved in the on-farm N rate trials were appreciative of the study and interested to see the results.

A main component of NESARE project “Winter triticale or rye as a double crop to protect the environment and increase yield” (LNE14-332), was to develop an N recommendation system for winter cereals grown as forage in New York. The findings of this grant (GNE15-108: Unraveling the milk production potential of winter cereals grown as forage double crops in corn or sorghum rotations) contribute to the determination of such as recommendation system as not just yield but also quality is impacted by fertility management and harvest processing. Additionally, the larger rotation study for which samples were analyzed, will answer questions about growing two crops in a growing season, taking into account production of the main crop. These studies combined will provide management options that could aid in timing of planting and/or harvesting and optimize crop performance.