Final report for GNE20-227

Project Information

Agri-environmental issues due to intensive agricultural production activities are of concern across the globe and specifically in the United States (US). Agri-environmental programs have been implemented by governments in affected countries including the US to address the negative environmental impacts of agriculture. A suite of conservation programs referred to as Farm Bill conservation programs (e.g., Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) sponsored by the US Federal government provide technical and financial assistance to farmers and other rural land managers in exchange for their voluntary adoption of best management practices (BMPs) to address resources concern resulting from agriculture. The planning, policy development, and implementation of these programs encourage partnerships among government-sponsored conservation agencies and other public-private conservation agencies as well as public participation at the federal, state, and local levels of decision-making. Partnerships and public participation are encouraged in conservation policy since it helps to account for public concerns, increase understanding of resource concern priorities, increase acceptance of the resultant program, and improve the efficient use of program resources and achievement of program goals. However, there is limited research conducted to explore the extent of public participation in program planning and implementation as well as how farmers make decisions to either participate or not participate in these government-sponsored agri-environmental programs. Consequently, drawing on the environmental governance (EG) framework, this project sought to evaluate the implementation of and farmers’ participation in the Environmental Quality Incentives Program using Pennsylvania as a case study organized around three objectives:

- Examine how national priorities of natural resources conservation affect the structure and implementation strategies of the program at the state and local level and the overall program success overtime at these levels.

- Examine the different factors that facilitate and/or constraint the ability of NRCS and local conservation district field staff to conduct recruitment and outreach activities to secure the participation of farmers in EQIP.

- Identify motivators and constraints to farmers’ participation or non-participation in the Environmental Quality Incentives Program.

Environmental governance (EG) has been used as a conceptual framework to explain the arrangements between state and non-state actors in achieving collective natural resources conservation goals (Heikkila and Gerlak, 2005; Manfredo, Teel, Sullivan, & Dietsch, 2017). Focusing on four of the five key issues or concepts of EG identified by Armitage et al. (2012) including adaptiveness, flexibility, and learning; knowledge co-production from diverse sources; new actors and their roles; and accountability and legitimacy except fit and scale, the findings of the first objective showed the presence of certain components of the four concepts in program planning and implementation processes, mainly because program decision-making processes and implementation practices are informed by congressional mandates and legislation. There is the participation of diverse stakeholders and conservation agencies in program processes at all three levels of decision-making and stakeholders play diverse roles in enhancing the achievement of program objectives. The findings of the second objective showed that mostly government conservation agencies, their partners, and stakeholders work together and sometimes separately to conduct program outreach utilizing a variety of communication channels and delivery methods. The key outreach approach relied on by both government and non-government agencies is “word of mouth” to disseminate program information. The study findings indicate that farmer-related challenges (e.g., costs associated with program participation, anti-government sentiments, bureaucracy, and inadequate awareness about program existence and goals) and program-related challenges (e.g., staff capacity, attitude, and knowledge about agriculture, inadequate funding, bureaucracy, inflexible program rules, regulations, and internal policies, etc.) could hinder program implementation at the local level. Finally, the findings of the third objective showed that program-related characteristics (e.g., cost share, environmental benefits, etc.) and personal reasons (e.g., environmental stewardship, social recognition for conservation efforts, etc.) as motivators for program participation. Self-autonomy and distrust of government conservation agencies, inadequate information on EQIP goals and benefits, religious reasons, and perceived limited knowledge of the heterogeneity of farms among conservation staff were some of the barriers to program participation.

In Summary, the study findings highlight program governance issues that could be improved to enhance public participation, support, and buy-in for conservation programs. Overall, the findings could improve understanding of how national-level decisions about natural resources conservation influence implementation decisions at the state and local level as well as farmer participation in EQIP. More generally the findings could enable states in the northeast region, particularly, Pennsylvania to secure conservation gains and enhance farmer participation in conservation programs such as EQIP over time.

Objective 1: Examine how national priorities of natural resources conservation affect the structure and implementation strategies of the program at the state and local level and the overall program success overtime at these levels.

Objective 2: Examine the different factors that facilitate and or constraint the ability of NRCS and local conservation district[1] field staff to conduct recruitment and outreach activities to secure the participation of farmers in EQIP.

Objective 3: Identify motivators and constraints to farmers’ participation or non-participation in the Environmental Quality Incentives Program.

Objective 4: Develop evidence-based recommendations for practices and procedures that help conservation field staff effectively work with farmers to promote sustainable agriculture and improve environmental quality.

[1] Field staff of the local conservation district will be selected to participate in the study because their outreach activities include informing farmers about the different conservation programs available to producers. Hence, for this project, NRCS and local conservation district field staff are referred to as the conservation field staff.

The purpose of this project was to identify how EQIP planning and implementation decisions at the Federal, State, and Local levels affect program implementation at the state and local levels, examine the different factors that facilitate and or constraints the ability of NRCS and local conservation district field staff to conduct recruitment and outreach activities to secure the participation of farmers in the program and identify factors that promote or hinder Pennsylvania farmers' participation in the government-sponsored conservation program using EQIP as a case.

Farmers’ voluntary participation in incentive-based conservation programs such as EQIP and subsequent adoption of conservation practices can help address environmental problems as well as sustain farm productivity (Cocklin et al, 2007). Farmers’ participation in EQIP can help Pennsylvania reduce nutrients and sediment levels in the Chesapeake Bay by 2025 (Wright, 2006). The EQIP is implemented by the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), to help farmers address environmental problems and promote sustainable agriculture production by providing monetary and technical assistance for the installation of conservation practices on working farmlands (Wright, 2006; Oliver, 2019). Given the crucial role of farmers’ voluntary participation in achieving EQIP outcomes, it is important that research is conducted to understand what type of farmer participates or does not participate in EQIP (McCann & Nunez, 2005). These research findings are important for addressing barriers that hinder farmers’ participation decisions. Previous studies have shown that constraints including financial costs (Carlisle, 2016; Yang & Sharp, 2017); lack of or inadequate knowledge about the existence of EQIP and its purpose (Oliver, 2019), limited knowledge about the how the adoption of conservation practices can benefit farm enterprise and improve environmental quality including water quality and soil health (DeVuvst & Ipe, 1994; Feather & Amacher, 1999; Liu, Bruins, & Heberling, 2018) affect farmers’ participation. In addition, historically underserved farmers are less likely to participate in such programs (Gan et al, 2005; McCann & Nunez, 2005).

Furthermore, program implementation strategies such as visits of conservation field staff to farmers (Obubuafo, 2006), choice of outreach and farmer recruitment strategies (Bruening & Martin, 1992; Mancini et al., 2008; Sosa et al, 2013), and unavailable support to farmers for completing required enrollment paperwork (Oliver, 2019) could inhibit participation. For Pennsylvania, non-participation of farmers in EQIP could hinder the number of conservation practices adopted which in turn affect its nutrition reduction goals in the Chesapeake Bay by 2025. Few studies have examined limitations to farmers’ participation in EQIP in the context of Pennsylvania (e.g. Wright, 2006). Furthermore, few studies have focused on examining recruitment and outreach practices used by conservation field staff and how these relate to farmers’ participation in these programs.

This project filled these gaps by (1) examining how national priorities of natural resources conservation affect the structure and implementation strategies of the program at the state and local level and the overall program success overtime at these levels, 2) describing recruitment and outreach strategies of conservation field staff involved in EQIP as they relate to farmers’ participation decisions, and 3) identifying motivates and or hinder farmers from participating in Pennsylvania EQIP. Additionally, the project makes recommendations for how NRCS can more effectively engage farmers to adopt conservation practices that improve water quality and secure the socio-economic, and environmental sustainability of agriculture through increased participation in EQIP. It suggests ways the federal government through its mandated agency for farm bill programs implementation, the NRCS, can work with other conservation agencies and the public to increasingly make conservation policies tailored to local needs, agri-environmental and climatic conditions.

Cooperators

Research

Review of the literature

January to July 2020 (not covered under NE SARE grant) - This project began with a review of the scholarly work related to agri-environmental conservation programs and their impact of promoting sustainable agriculture and conservation of natural resources. The review process focused on identifying publications that have documented the structure of conservation programs and strategies employed by conservation agencies in the implementation of programs. It also identified studies that documented the experiences of farmers who participate in conservation programs as well as the outreach and recruitment practices used by conservation field staff to recruit farmers in the conservation programs. This literature shows that conservation practices adoption by farmers through Farm Bill conservation programs such as the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) can contribute to water quality improvement goals in local waterbodies. EQIP is one of the largest working lands programs among a host of conservation programs in the United States (Congressional Research Service, 2019; Reimer, Gramig, & Prokopy, 2013). It was created by the 1996 Farm Bill to provide cost-sharing, technical, and educational assistance to improve farmers’ voluntary participation in the program (Lubell et al., 2013). For EQIP, farmer participation is defined as the adoption of any or all recommended conservation practices that address the environmental effects of agriculture. Studies have shown that EQIP participation has yielded benefits to the farmer such as improved soil fertility, yield improvements, and nutrient retention on the farm, critical for sustained agricultural productivity and farm profitability (NRCS, 2019). In addition, EQIP participation has yielded environmental benefits such as improvement in local water quality (Agourdis, Workman, Warner, & Jennings, 2005; Lui, Wang & Zhang, 2018) and economic stability of farms (Bruce, Farmer, Maynard, & Valliant, 2017). Consequently, farmers’ improved participation in EQIP could serve as a crucial avenue for Pennsylvania to address water quality goals in the Chesapeake Bay watershed. To be able to improve farmers' participation in EQIP, NRCS and its partner implementation organizations should understand the factors that influence farmer’s participation decisions.

The literature on farmer participation in conservation programs has shown challenges such as farmers’ inadequate access to information on the existence and purpose of conservation programs (Oliver, 2019; Carlisle, 2016; Reimer, Weinkauff, & Prokopy, 2012; Yang & Sharp, 2017), limited knowledge about how conservation practices benefit farm enterprise and environment (DeVuvst & Ipe, 1994; Feather & Amacher, 1999; Liu, Bruins, & Heberling, 2018), inadequate visits of NRCS staff to farmers (Obubuafo, 2006; Oliver, 2019), farmer challenges for completing required enrollment paperwork (Oliver, 2019). Addressing the challenges that hinder participation in conservation programs could improve farmer participation (Reimer & Prokopy, 2014), which is critical to improving agricultural productivity and profitability and improved environmental health (NRCS, 2019). A growing body of research strives to recognize how recruitment strategies employed by conservation agencies staff relate to farmers’ participation in programs (Bruening & Martin, 1992; Mancini et al., 2008; Sosa et al, 2013). By identifying how NRCS staff responsible for EQIP farmer recruitment carry out their duties and the challenges that hinder staff from performing their duties, this project made recommendations for outreach that could help conservation agencies and thier field staff work more effectively to sustain conservation gains and the sustainability of the agriculture sector through adaptation of recruitment and outreach practices.

Following the literature review, I submitted an Institutional Review Board (IRB) application to the Pennsylvania State University IRB office. I developed the IRB protocol for human subject research for this project. The protocol documented the project objectives, scientific background and gaps in current knowledge, study rationale, the criteria for inclusion and exclusion for potential project participants, and the participant recruitment methods. In addition, the project’s consent process, details the project’s study design and procedures (details described below), and a confidentiality, privacy, and data safety and management plan for information collected during the project’s timeline are documented in the IRB protocol. Further, I submitted interview guides which included questions that will be asked to study participants during the interviews. All the documents were reviewed by a designated Penn State IRB officer. The IRB application was approved after revision (one time) at the “Exempt” level. The project IRB was approved on September 21, 2020. After conducting a majority of the farmer interviews, I submitted an IRB application for the Farmer survey on December 30, 2021 and this application was approved on January 14, 2022 at the "Exempt" level.

August 2020 to January 2021 (NE SARE funding for this project began on August 1st, 2020) - As stated in the submitted proposal, this period was designated for data collection for this project. However, due to the Coronavirus Pandemic and changes in data collection procedures at Penn State University, this activity could not occur as planned. Nonetheless, the period was spent consulting with the USDA NRCS staff including, State Conservationist, Supervisory District Conservationists, and District Conservation Directors to identify and recruit potential participants among farmers and conservation field staff respectively from Centre, Bedford, and Lebanon Counties.

February 2021 to August 2022 –Primary data collection for this project began in February 2021. A multimethod research design using in-depth interviews, document analysis, and participant survey was utilized in data collection.

Project Methods

Research Approach: This socio-behavioral science project used an exploratory sequential multimethod research design to collect data that addressed the project objectives. Exploratory sequential multiple methods allow the researcher to gain an in-depth understanding of an under-researched topic and compare the results of the qualitative and quantitative research approaches (Creswell & Clark, 2017; Kolar, Ahmad, Chan, & Erickson, 2015). To collect data, this project used in-depth interviews in combination with surveys of farmers and conservation professionals, service providers, and field staff operating in Pennsylvania’s part of the Chesapeake Bay watershed. At the US federal level, a suite of conservation programs referred to as Farm Bill conservation programs (e.g., Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) provide technical and financial assistance to farmers and other rural land managers in exchange for their voluntary adoption of best management practices (BMPs) to address resources concern resulting from agriculture. The planning, policy development, and implementation of these programs encourage partnerships among government-sponsored conservation agencies and other public-private conservation agencies as well as public participation at the federal, state, and local levels of decision-making. However, there is limited research conducted to explore the extent of public participation in program planning and implementation as well as how farmers make decisions to either participate or not participate in these government-sponsored agri-environmental programs.

Drawing on the environmental governance (EG) framework and the diffusion of innovation theory, this project sought to address the research gaps by utilizing qualitative and quantitative methods (multi-method) of inquiry to address the project objectives. Environmental governance (EG) has been used as a conceptual framework to explain the arrangements between state and non-state actors in achieving collective natural resources conservation goals (Heikkila and Gerlak, 2005; Manfredo, Teel, Sullivan, & Dietsch, 2017). Environmental governance is a framework that refers to the means and arrangements by which society determines and achieves environmental management goals (Dreissen, Dieperink, van Laerhoven, Runhaar, & Vermulen, 2012). It encompasses mechanisms, regulations, and processes that guide decision-making and implementation (Dreissen et al., 2012). EG is used as an analytic framework to evaluate institutions that bind different actors together in collaborative arrangements and highlight the rules which guide interactions and actions among and between actors (Evans, 2012). It can also be used to identify which stakeholders participate in governance decisions and examine the extent to which sustainable environmental management policies are representative of the inputs of the state and non-state actors (Benson and Jordan, 2017; Bridge & Perreault, 2009, Folke, Hahn, Olsson, and Norberg, 2005). State actors represent government interest and institutions, while non-state actors represent the interests/needs of society. Through EG, state and non-state actors work together to improve understanding of environmental problems among stakeholders, provide support for innovative policy for addressing environmental problems through voluntary mechanisms as well as identifying relevant resources for implementing policies and enhancing successful policy implementation (Scott, 2015).

Armitage et al. (2012) present five key issues or concepts of EG following a detailed review of the literature including adaptiveness, flexibility, and learning; knowledge co-production from diverse sources; new actors and their roles; and accountability and legitimacy and fit and fit and scale. This study focuses on all the key issues/concepts identified by Armitage et al. (2012) except fit and scale to assess the extent to which the decision-making process and implementation of EQIP follow the tenets of EG. Adaptiveness, flexibility and learning concept encompasses the ability of the governance system and decision-making processes to be amenable to change in the face of uncertainty or disturbances (Armitage et al 2012). Key to achieving adaptiveness, flexibility, and learning is through monitoring, learning by doing, and developing and sharing knowledge through collaboration between the different governance actors (Armitage et al, 2012; Folke, Hahn, Olsson, & Norberg, 2005; Scott, 2015). An EG arrangement can be considered to be adaptive when structures for revision and deliberation are established through practice or officially recognized through organizational practice or customs. Thus, there are established processes to revise and develop policies, institutions, and adjust management decisions/actions to reflect uncertainties and new knowledge (Bennett and Satterfield, 2018). The knowledge co-production concept reflects activities aimed at generating knowledge from different actors across complex and unstable systems to achieve collective goals. Co-produced knowledge from diverse sources and types could be important for identifying and understanding common environmental issues (Manfredo, Teel, Sullivan, and Dietsch, 2017; Rathwell, Armitage, and Berkes, 2015) as well as ensuring that policy for tackling environmental problems represent a fair balance of local conditions and values and scientific knowledge (Lockwood et al., 2010).

The next concept relates to actors and their roles in EG. Actors include state actors and non-state actors including local communities, non-governmental organizations, private industry, individuals, scientists, and other relevant stakeholders with an interest in conservation (Bennet and Satterfield, 2017; Lemos & Agrawal, 2006). Clearly defined roles and interactions of non-state actors in EG could potentially increase their ability to support effective decision-making (Armitage et al, 2012). Participation of non-state actors could provide the capacity needed for addressing the agri-environmental problem, through partnerships that build mutual engagement among stakeholders and potential actors and enhancing the identification of problems across all levels of government decision-making (Lockwood et al., 2010). The final concept is accountability and legitimacy which is reflected as clearly defined roles and responsibilities; penalties for performance; responsiveness; transparency; free flow of information and improved communication between participating actors (Bennet and Satterfield, 2017). The practice of EG in addressing environmental issues could promote information sharing, trust building, and learning among actors which are necessary for developing innovative, adaptive, and resilient responses to environmental problems (Benson and Jordan, 2017).

In this project, we use EG as an analytical framework to explore the extent to which formal institutions guide the partnership or collaborative arrangements between Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) and other state and non-state actors and the boundaries within which these actors interact (Evans, 2012) with respect to EQIP planning and implementation. Further, we use EG to identify who participates in governance decisions as well as examine the extent to which policy and proposals for addressing environmental degradation are inclusive of diverse inputs from both state and non-state actors that represent the interests of society (Bridge & Perreault, 2009; Manfredo, Teel, Sullivan and Dietsch, 2017; Rathwell, Armitage, and Berkes, 2015).

The multimethod research approach allowed the of use several data collection methods to investigate the research objectives (Seawright, 2016). Given the complexity of conservation program implementation as well as farmers’ decision to participate in these programs, the use of multimethod approach allowed the researcher to comprehensively document “reality” and develop a nuanced understanding of the complex research problem and context (Brewer & Hunter, 2006; Meijer, Verloop, Beijaard, 2002). Further, the multimethod approach enabled the researcher to combine different data collection methods based on the needs of the individual research objectives rather than mixing qualitative and quantitative methods for each objective (Brewer & Hunter, 2006). Finally, the multimethod approach provided a basis for enhancing the validity of the study findings by enabling the researcher to understand the relationship between program structure and implementation practices and farmer participation from multiple perspectives (farmer, public conservation agencies, and private conservation agencies) (Laplante & Nolin, 2014; Meijer, Verloop, & Beijaard, 2002; Seawright, 2016).

Research Questions: Informed by the research objectives enumerated earlier, the following questions listed below were developed to guide the research:

- To what extent does EQIP planning and implementation processes at the federal, state, and local levels follow the tenets of environmental governance?

- What are the outreach and recruitment practices used by conservation agencies such as the NRCS and their field staff in securing farmers’ participation in government-sponsored conservation programs such as EQIP?

- What factors facilitate and/or constrain the ability of conservation agencies to conduct outreach and recruitment for conservation programs?

- What are the perceptions of conservation field staff about the factors that could hinder the successful implementation of conservation programs?

- What motivates farmers to participate in government-sponsored conservation programs such as EQIP?

- What are the barriers farmers face in making decisions to participate in government-sponsored conservation programs?

Data Collection

This section describes the different data collection methods used in this research and is organized according to the three research objectives.

Objective One: The data needed to address this objective were collected through in-depth interviews with key persons who are involved with the planning and implementation of conservation programs and through review and analysis of program documents (Yin, 2014). I conducted sixteen interviews with representatives from government conservation agencies and non-profit organizations including USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), the American Farm Bureau Federation (AFBF), an organization for commercial farmers in the nation (Medina, Isley, & Arbuckle, 2020; Lenihan & Brasier, 2010), the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition, the lobbying and advocacy branch of the national sustainable agriculture movement (Lenihan & Brasier, 2010), USDA Farm Service Agency, Pennsylvania Farm Bureau, the Pennsylvania State Conservation Commission, which provides support and oversight responsibility to all the county conservation districts for the implementation of conservation programs, the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, a regional partnership program that spearheads effort to restore water quality in the Chesapeake Bay watershed, one Technical Service Provider, Pheasants Forever Inc. and Berks Nature, both representing non-profit conservation organization. These agencies and organizations play diverse roles in the planning and implementation of EQIP at the national, state, and local levels.

The interview participants were selected using purposive and snowball sampling, based on their role in EQIP program planning and implementation and their experience with program decision-making processes (Babie, 2015; Bernard, 2017; Moon et al., 2017). Participants were interviewed using an interview protocol guided by the research questions, literature review, and the theoretical framework that informed that study. The interview guide had questions that asked about the role state and non-state actors play in the planning and implementation of EQIP, participants’ perspectives about the receptiveness of NRCS to the inputs of diverse actors in program planning, and inclusion of diverse perspectives in program implementation, the role of partnerships and public participation in affecting program changes and adjustments. The interview questions also sought to identify the factors that facilitate successful delivery of the program and participants’ concern about program planning, administration, and implementation (Ritchie & Lewis, 2003). The interview guide was reviewed by a panel of experts with experience qualitative research, human dimensions of natural resources management, and agricultural extension. The interview guide was revised to improve the readability and the ordering of the questions to improve flow of the interview process. The interviews were conducted virtually over zoom and Microsoft teams and lasted between 30 – 90 minutes. All interviews were recorded with the participant's permission and transcribed using a professional transcription service. The EG concepts that guided the study were operationalized as follows:

- Adaptiveness, learning, and flexibility: adaptiveness was operationalized as the changes and adjustment in program practices and processes resulting from new knowledge and expertise shared by the diverse participating stakeholders in planning and implementation processes. Leaning was operationalized as new knowledge and experiences useful in learning about natural resources priority of concern and solutions for addressing them drawing from diverse stakeholder perspectives. Flexibility referred to the authority given to NRCS by Congress to make program decisions

- Knowledge co-production was operationalized as both formal and informal laid down processes and avenues that allow diverse conservation agencies and stakeholders to engage with NRCS to achieve conservation program goals.

- Actors were conceptualized as other state conservation agencies, non-state conservation agencies, agricultural institutions, and other relevant stakeholders with interest in agricultural conservation.

- Legitimacy was operationalized as acceptance of the authority of NRCS in making conservation program decisions by the different categories of stakeholders, as backed by legislation and programs, who participate in the governance processes for EQIP. Accountability was operationalized as the different activities were taken to measure the efficient use of program resources and determine program outcomes.

Policy statements and legislative documents, (Medina et al., 2020, 2021; Lenihan & Brasier, 2010), and program implementation documents were also analyzed as part of this study. These documents included the 2018 Farm Bill (Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018), EQIP Manual, 7 C.F.R. part 1466 (7 C.F.R. § 1466) and 7 CFR Part 610. The documents were obtained through a search of the government database for public laws and the Code of Federal Regulations (Del Rossi, Hecht, and Zia, 2021).

Objective two: To address objective two, in-depth interviews were conducted with 17 conservation field staff from both government sponsored organizations and non-profit conservation organizations whose work involve outreach and education activities to farmers about Farm Bill Programs such as EQIP located in Pennsylvania’s portion of the Chesapeake Bay Watershed. The interviewed conservation field staff for the government agencies included representatives of United States Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service (USDA NRCS), an agency mandated with the planning, administration, and implementation of the EQIP, and representatives from the County Conservation District. Representatives of non-profit environmental groups interviewed included Pheasants Forever, Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay, Clearwater Conservancy, and The Nature Conservancy, representative of the American Farm Bureau Federation (AFBF), an organization for commercial farmers (Medina, Isley, & Arbuckle, 2020; Lenihan & Brasier, 2010). The organizations were selected for the interviews based on their support for the development and implementation of EQIP through their conservation outreach activities (Medina, Isley, & Arbuckle, 2021). The representatives were selected using purposive and snow-ball sampling methods based on the criteria that their work involved participating in EQIP development and implementation processes across the counties as well as conducting outreach or communicating the program to potential participants to secure farmers’ participation in conservation programs, particularly EQIP, and have spent at least one year working in that capacity. Purposive sampling is appropriate for this phase of data collection because it allows the researcher to explore the outreach and recruitment practices of conservation field staff who have relevant knowledge and experience about the research topic (Babie, 2015; Bernard, 2017). Each interview was conducted remotely via zoom and/or telephone, lasted a minimum of 25 minutes and was audio-recorded with consent from each participant.

A semi-structured interview guide was developed following the research questions and a review of the literature to elicit information from the study participants. The interview guide had questions that asked participants to share their experiences and perspectives regarding 1) what roles they play in creating awareness among farmers about the existence of conservation programs, such as the Environmental Quality Incentives Program; 2) what specific communication channels they use in conducting educational activities for farmers about EQIP and encourage them to participate in the program, 3) what are the constraints (if any) they face in conducting recruitment and outreach activities for farmers, and 4) what are their perceptions of weaknesses of EQIP in relation to program administration and implementation.

Objective three: Data for this objective were collected using a multimethod approach to address the research questions. Both qualitative and quantitative data were collected during the study period (Creswell & Plano-Clark, 2007) in two interrelated phases. The results from both phases were given equal value and integrated into addressing the research questions by comparing the two forms of results. The use of these two data collection methods has several advantages. First, the researcher could explore EQIP (non-) participation from the farmer’s lived experience using both qualitative and quantitative data to overcome the limitations associated with using either a qualitative or quantitative approach only in exploring the topic (Hammond, 2005; Johnson & Onwuegbezie, 2004). Second, the use of both qualitative and quantitative data allows the researcher to gain an in-depth understanding of different factors that influence farmers’ behavior and perspectives by comparing the results from the interviews and the survey (Hoshmand, 2003; Kelle, 2006). As posited by Reimer and Prokopy (2014), the use of multiple methods allows the researcher to move from solely depending on quantitative factors related to program participation to explore influencers of and/or constraints to participation considering the context within which farmers’ participation decisions are made and their lived experiences.

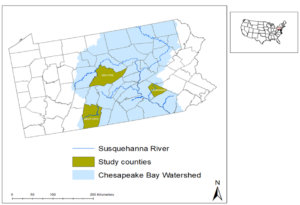

Study Site and Target Population: The target population consisted of livestock and crop producers with operations in Pennsylvania’s part of the Chesapeake Bay watershed as shown in Figure 1. According to the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (PA-DEP) (2019), there are 33,000 farms located in 43 counties in the watershed. These producers could help address 80% of water quality degradation in the Bay mainly through the adoption of BMPs that reduce nutrients and sediment runoff from farms and at the same time improve farm productivity (PA-DEP, 2019, 2020). Thus, the Chesapeake Bay watershed provides an optimal location for this project. The 43 counties in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed have been categorized into four Tiers based on their contribution of agricultural non-point source pollutants into the Bay through local water sources (PA-DEP, 2019). According to the categorization, Tier one counties are perceived as the high contributors of agricultural non-point pollutants to the Bay (PA-DEP, 2019) followed by Tier two, three and four counties. This study focused on tier two counties because we wanted to avoid participants' fatigue in Tier one counties because there was an ongoing survey in the Tier one counties to assess non-cost share adoption of BMPs at the time of developing and implementing this research. Out of five counties in tier two counties, three counties, Lebanon, Bedford, and Centre County, were randomly selected as for the research.

Lebanon County

The county is mostly drained by the Swatara Creek into the Susquehanna River. Approximately 1,993 farmers are managing 1,149 farms in the county (United States Department of Agriculture, 2017). The average farm size in the county is slightly more than 90 acres with a total of 107, 577 acres of land under agricultural production (USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service (USDA NASS, 2017). Poultry is the common livestock raised by farmers in the county. More than 80% of the county falls within the Chesapeake Watershed (Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, 2018; Wright, 2006). As of 2017, the total earnings from agriculture were approximately $351 million dollars, placing the county among the top five agricultural producers in Pennsylvania (USDA NASS, 2017).

Centre County

The county as its name suggests is in central Pennsylvania. The county is drained by the Susquehanna River which forms part of the Chesapeake Bay watershed. As of 2017, 1,183 of the population in the county were engaged in agricultural production. There are 1023 farms in the county that are operational on approximately 150,000 acres with an average farm size of 146 acres (USDA NASS, 2017). Crop production represents a major agricultural land use activity covering an estimated 59% of the agricultural land. As of 2016, the total earnings from the sale of agricultural produce were $ 91 million, placing the county at the 24th position among the counties in the state (USDA NASS, 2017).

Bedford County

The county is part of southern Pennsylvania and is drained by the Juniata River and tributaries of the Potomac River which are part of the Chesapeake Bay Watershed. The 2017 USDA agricultural census puts the population involved with agricultural production at 1,948 (USDA NASS, 2017). There are 1,159 farms in the county operating a total of 222,224 acres of farmland with an average farm size of 192 acres (USDA NASS, 2017). Crop production represents the main agricultural land use, covering 54% of the estimated agricultural land. Forage, which includes hay and haylage is the most popular crop produced by farms in the county followed by corn for grains and corn for silage or green chop. According to the 2017 agricultural census, the total earnings from agricultural sales were approximately $115 million placing the county in the 18th position within the state.

Qualitative Data Collection: First, I conducted in-depth interviews to explore farmers’ perceptions about and experiences with EQIP and their program (non-) participation decisions. A total of 27 interviews were conducted with purposively selected farmers with operations in the Centre, Bedford, and Lebanon counties. The study participants were recruited with the help of staff from NRCS, Penn State Extension, and County Conservation District, and exploring the website of agricultural commodity groups. Interview participants were selected based on the following criteria: participants must identify as either grain and or livestock farmers, must earn at least $1000 annually from the sale of produce per USDA standards for classifying farmers, with or without a history of participation in EQIP, and reside in the selected counties. Twenty-one interviews were conducted through zoom and/or by telephone with the remainder being in person at the farmers’ residence or farm from Winter 2021 through early summer 2022. I sought the consent of the interview participants verbally before proceeding with the interviews after reading the IRB-approved oral consent script.

A semi-structured interview guide with pre-determined questions was developed by considering the research questions and a review of the literature and used in interviewing the study participants (Rubin & Rubin, 2012). The interview guide was used since it enhances flexibility during the interviews and allows the participants to respond to issues that are essential to their understanding of their experiences (Patton, 2015). The interview guide included questions about participants’ farm production goals and practices, EQIP participation status, as well as their interactions with conservation field staff. In addition, participants were asked to describe how and why they make decisions to either participate or not participate in EQIP. All the interviews were documented using audio recordings and handwritten notes were taken, when possible, with permission from participants. The recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim by using the services of a professional transcription company, Rev.com. The interview transcripts were cleaned for subsequent analysis using NVivo Qualitative Analysis software.

Quantitative data collection: To quantitively measure farmers’ perceptions about and experiences with EQIP and their program (non-) participation decisions, I developed a mail survey following Dillman et al. (2014) Tailored Design Method. Insights from the farmer interviews and the literature review were incorporated into the survey design. The survey had four parts. The first part asked respondents to indicate their motivation for participating in or willingness to participate in EQIP, their attitudes towards EQIP, and the barriers that hinder farmers from participating in the program. Farmers’ motivations (N = 16) was measured using a four-point Likert scale. Survey participants were provided with a prompt: I will apply to participate in a conservation program (e.g., EQIP) if it (e.g., provides cost share for installing BMPs on my farm, etc.). The Likert scale ranged from 1 = “Strongly agree” to 4 = “Strongly disagree”; no neutral option was provided. We used a five-point Likert scale to measure perceived barriers to program participation. Survey participants were provided with a prompt: Farmers may not apply to a Farm Bill conservation program (e.g., EQIP) because (of) (e.g., the complexity of program eligibility requirement(s). The Likert scale ranged from 1 = “Strongly agree to 5 = “Strongly disagree”.

I collected information on respondents’ demographic characteristics in the final part of the survey. I measured the age of the respondents on a continuous scale which was computed based on the respondent’s year of birth. The respondents’ highest education level was coded as 1 = “Some high school or less”, 2 = “High school diploma or GED”, 3 = “Vocational/technical school/some college”, 4 = “Four-year college degree”, and 5 = “post-graduate degree”. I also collected information on respondents’ gender, race, and membership in a farmer-based organization. The gender of the respondent was coded as 1 = “Asian/Asian American”, 2 = “Black/African American”, 3 = “Caucasian/White”, 4 = “Indigenous Peoples”, 5 = “Other (please specify)” and 6 = Prefer not to answer. Gender of the respondent was coded as 1 = “Male”, 2 = “Female”, 3 = “Other (Specify)” and 4 = “Prefer not to answer”. Finally, respondents' membership in a farmer-based organization was measured on a binary response (yes/no) scale.

To establish the content and face validity of the survey instrument, a panel of experts was set up and assessed the instrument to identify any potential challenges that intended users may face in completing the instrument and to examine the accuracy of the instrument in addressing the research objectives (Kumar Chaudhary & Israel, 2016; Presser et al. 2004). The panel of experts with comprehensive knowledge and/or experience in human dimensions of natural resources management, survey design, and farmer behavior was put together. The panelists were associated with Penn State University, state Extension specialists, and state conservation experts. I reviewed and incorporated recommendations from the panel to improve the survey instrument. Two questions which were measuring the program accountability and compliance as well as farm income were deemed sensitive by the expert panel and were removed from the survey.

The updated instrument after feedback from panelists was pretested with a group of six farmers using cognitive interviews (Dillman, 2000; Dillman et al., 2014). Following Ouimet, Bunnage, Carini, Kuh, and Kennedy, (2004), we conducted these interviews to determine 1) how farmers interpret the items and their response options, 2) if the items are clearly worded and are specific enough to yield reliable and valid results, and 3) if the items and their response categories were an accurate depiction of farmers' lived experience and perceptions about Farm Bill conservation programs, such as EQIP. The responses from the farmers were used to improve the wording of the instructions for the survey sections one through four and some of the survey items.

The most common errors that occur while conducting a survey include coverage error, measurement error, sampling error, and non-response error. The coverage error in a survey occurs when the sampling frame for the study does not accurately reflect the target population on one or more characteristics of interest (Dillman et al., 2014). In this study, coverage error was addressed by sampling from the database of DTN, an Agriculture Marketing and Consultation firm to obtain an accurate and up-to-date sampling frame possible. Measurement error is the difference between what study items are intended to measure and what the study items really measured (Dillman et al., 2014). Measurement errors can occur due to unclear wording of survey items, poor choice of survey items, scales, or response options. In this study, measurement error was addressed through expert panel review of the survey and cognitive interviews.

Another error that can affect survey validity is sampling error. Sampling is the difference between a population parameter and the statistic estimated from a sample of that population (Dillman et al., 2014). This error occurs when the study sample does not accurately represent the population. In the study, the potential participants were oversampled to achieve a target margin of error of ± 5% to reduce the chances of sampling error occurring. Non-response error occurs when some members of the sample do not respond to the survey and there are differences in characteristics between survey respondents and non-respondents that could influence the survey results (Dillman et al., 2014). To address non-response error, we compared early and late respondents on two key variables – motivations of and barriers to EQIP participation. The results of the independent samples t-test showed no significant differences between the early and late respondents, t (130.224) = .509, p = 0.612.

The survey was administered to a random sample of farmers across the Center, Bedford, and Lebanon Counties. The sampling frame was developed by working with an Agriculture Marketing and Consultation firm, DTN, which had the physical mailing, telephone, and email contact information of most producers in the selected counties. The researchers requested that each participant selected should have physical mailing contact information. Following sampling procedures recommendations by Krejcie and Morgan (1970), we needed a selected sample of 1200 for a 97% confidence interval and a 3% margin of error. Table 1 describes the sample frame.

Table 1 Description of Sample Frame

| Description of Frame | Sample Numbers |

| Original sample frame | 1200 |

| Cleaned sample frame: Undeliverable | 23 |

| Cleaned sample frame: Not interested | 3 |

| Cleaned sample frame: no longer farming or not a farmer | 37 |

| Surveys discarded: deceased | 12 |

| Surveys discarded: blank | 124 |

| The final count of sample | 1001 |

Survey data for the study was collected from May to July 2022 following a modification of Dillman’s five-point, Tailored Design Method (Dillman, Smyth, & Christian, 2014). Four mailings of the survey and accompanying documents occurred over the data collection period to reduce survey non-response. On May 27, 2022, a pre-notification was mailed to all 1200 participants. Five days later, on June 1, 2022, a survey packet that included the survey instrument, a cover letter, and a postage-paid return envelope was mailed to all 1200 participants. Two weeks after the initial mailing, on June 17th, a reminder notification was mailed to participants who were yet to respond to the survey. At the end of the first mailing (June 20), a total of 67 usable surveys had been received. Approximately, three weeks later, on July 1, 2022, a second survey packet was sent to the remaining participants. No reminder was sent to the non-respondent due to logistical constraints and the survey ended on July 30th, 2022. In total, 162 out of the clean data sample of 1001 were used for analysis. The response rate (16.18%) for the survey was low compared to other studies that used farmer surveys (e.g., Reimer & Prokopy, 2012).

To ensure the reliability of the survey instrument, Cronbach’s alpha was run on two key questions reported in the study: 1) Motivation for EQIP participation, 2) Attitude, and 3) Perceived Barriers to EQIP participation. Table 2 shows Cronbach’s alpha for the main survey reported for EQIP participants and EQIP non-participants respectively.

Table 2 Reliability Report for Key Variables

| Concept | Number of items | Cronbach’s alpha | |

| EQIP Participants | EQIP non-participants | ||

| Motivation | 16 | .900 | .983 |

| Attitude | 7 | .847 | .956 |

| Barriers to program participation | 15 | .832 | .884 |

Data analysis

This section of the report describes the different approaches used in analyzing the data collected to address the different research objectives that guided the project. These analytical approaches are organized according to the data type.

In-depth interview data analysis: The interview data for Objectives One, Two and Three were coded following Case Study coding methods (Creswell & Poth, 2018) using the qualitative software package NVIVO (Version 12, QSR International, Doncaster, Australia). Three of the transcripts were randomly selected and read through to develop a general sense of the participant’s responses to the research questions and identify any patterns or concepts that exist (Yin, 2014). Initial codes were developed deductively using participants' words and descriptions (in Vivo coding) for each transcript for recurring themes based on the research questions. These initial codes were organized and used to develop the codebook for coding the remaining transcripts, and the codebook was revised when new codes were identified. Significant initial codes were identified from the previous step to establish patterns and similarities between two or more codes identified for each transcript (Creswell & Poth, 2018; Yin, 2014). Similar codes were grouped together to form subthemes, and superordinate themes were created by grouping the subthemes based on the research question and the conceptual framework (Creswell & Poth, 2018; Yin, 2014). Trustworthiness and dependability of the study findings was established through intercoder reliability. Following recommendations by Cofie, Braund, and Dalgarmo (2022) and O’Connor and Joffe (2020), a second coder with no knowledge about the interview transcripts but experienced in coding qualitative data was engaged to code a sample of the interview transcripts. The coder randomly selected and coded three transcripts using the initial codebook developed (Cofie, Braund, & Dalgarmo, 2022). The two coders met to discuss the codes in two separate meetings, and codes and themes were revised when needed to adequately reflect participants' responses and the themes identified. I used quantifiers such as “a few,” “some” and most” when reporting the findings to give readers a sense of how spread the perspectives are among interview participants (Chikowore and Kerr, 2020).

Document analysis: All the identified documents reviewed for the research were analyzed manually using applied thematic analysis procedures guided by the interview codes as well as allowing new codes to emerge (Guest, MacQueen, & Namey, 2012; Mackieson, Shlonsky, & Connolly, 2019). Each relevant document was read through to make sense of the document's content. Next, initial themes were noted, and appropriate codes were generated (Mackieson, Shlonsky, & Connolly, 2019). The documents were reviewed carefully, and codes were revised when necessary. Similar codes were organized under relevant subthemes, and similar subthemes under a common broader theme to address the research objectives with the aim of seeking convergence and corroboration by comparing the two data sources (Bowen, 2009; Mackieson, Shlonsky, & Connolly, 2019). To establish the credibility of the study findings, verbatim quotes from the interviews and extracts from the documents analyzed are used when necessary to support the study findings (Chikowore and Kerr, 2020).

Farmer survey data analysis: The survey data were analyzed using descriptive statistics such as frequencies, percentages, and means. In addition, inferential statistics such as independent samples t-test was used to analyze the difference in participants’ responses for non-response error. The resulting themes and codes from qualitative interviews were further compared with survey responses to identify areas of similarity and differences for Objective three (Creswell & Poth 2018; Yeboah 2014).

This section of the report presents the findings of the research, and they are organized according to the research objectives and/or research questions.

Result for Objective 1: Examine how national priorities of natural resources conservation affect the structure and implementation strategies of the program at the state and local level and the overall program success overtime at these levels.

To address this objective, I utilized data from interviews with conservation managers at federal, state, and local levels and program document analysis to explore the extent to which EQIP planning and implementation processes follow four concepts of environmental governance: adaptiveness, flexibility, and learning; knowledge co-production; acknowledgment of new actors and their roles; and accountability and legitimacy, as shown below:

Adaptiveness, flexibility, and learning

The findings of the interview data and document analysis showed opportunity for adaptation, flexibility, and learning in EQIP planning, administration, and implementation processes. From the document analysis, it was evident that NRCS is encouraged to establish structures (e.g., State Technical Advisory Committee, Local work group meetings, etc.) that allows the participation of diverse conservation stakeholders to engage in reflective activities and discussions about program processes and practices. Here, these diverse stakeholders give their input perceived to be relevant for program decision-making. Input refers to the knowledge and expertise of the stakeholders in relation to the agri-environmental program planning and implementation. The established structures give the opportunity for NRCS and the participating stakeholders to learn about new knowledge about the environmental issues necessary for making revisions and adapting/adjusting the policy and program actions to changing socio-ecological conditions and program participants’ needs. There exist formal and informal avenues for the NRCS at the federal, state, and local levels to engage with the public, other state, and non-state conservation actors to learn about new knowledge about environmental problems and how to address the problem through the program and identify probable ways to adapt management practices to the new knowledge gained. The formal avenues include public comments, consultative meetings,

NRCS at the federal, state, and local levels is mandated through program legislative and guiding documents to encourage the public, state, and non-state conservation organizations to share their observations, knowledge, and feedback about program practices during review periods to ascertain what can be changed or maintained about programs to enhance success. Observations, knowledge, and feedback could be provided on priority resource concerns, conservation practices to address identified resource concerns, program application ranking criteria, payment rates, economic and environmental impacts of conservation practices and programs, program rules and regulations, conservation and technical concerns and needs of diverse program audience such as historically underserved groups and individuals.

Depending on the nature of the recommended adjustments [ that is if the recommendation falls within mandatory or discretionary authority], NRCS may have the mandate to make the change in a particular funding cycle or wait for when the whole Farm Bill is being reviewed to forward these recommendations to Congress for adjustments in the program, what they deem appropriate. For example, decisions regarding program rule changes recommended by members of the public or non-state actors cannot be made by the NRCS and may have to be forwarded to Congress particularly if these inputs are received by NRCS after the program rules have been finalized. There was a consensus among participants that congressional mandates and limitations on NRCS influenced the incorporation of recommendations at the different levels of decision making as explained by a participant:

“... but you need to realize that the degree of flexibility they have in making actual program changes, is driven to a large degree by what's in their federal rule makings and the congressional mandates. That you just can't take EQIP and use those resources for something that's not consistent with those federal mandates. It has to be wholly consistent with what Congress has given them money for, and what they've tasked them with, and with the rule making that they make. So, while these programs that the state and local level can be modified to some minor degrees, what happens at the local level is primarily driven by what the congressional mandates and the federal rule makings are.” – [Interview 14].

Interview participants expressed the significant role of collaboration or partnerships and public participation in learning and making program adjustments where necessary in addressing resource concerns through information and knowledge sharing. Participants mentioned several instances where knowledge and information shared with NRCS has led to program adjustments at the federal, state, and local levels as explained by this participant:

“Well, I think one big change was because of an outside agency. We've always offered higher payment rates for historically underserved for like, I don't remember how many farm bills now. And they can also receive advanced payments to help procure the supplies and get the contractors in place. But there weren't a lot of people using that feature. So outside group did some poll data. They ask for data, and we give it to them, and they do an analysis. They came back and said, hey, you guys are doing really bad in this area. There's not a whole lot of people using this feature. So, it was written into statues .... We now have at offer on an item -by -item basis to any historically underserved producer, the advanced payment… It's the option for the advanced payment. Because it just wasn't being utilized compared to the number of EQIP producers, advanced payments is really low. So that's something an outside agency brought to our attention. And so, we now have built that into our training and into our software. There's a check box that has to be checked by the producer.” - [Interview 2]

Participants opined that sometimes adaptations to programs can occur when there is a change in the political leadership and/or a new congress. Adaptations in programs due to changes in political power were perceived as posing a challenge to program planning, implementation, and administration. Some participants opined that this change could potentially affect program continuity from previous program priorities, and funding particularly when the present administration’s goals for conservation is a departure from their predecessor’s. Others expressed that sometimes such change can lead to a focus on funding short-term program priorities that have limited impact on resource concerns in the long term. Consequently, some participants expressed the importance of keeping politics out of the program to minimize administration and implementation constraints as opined by these participants:

“It's existed this long for a reason and has been vital in making sure that our political nature that has developed over the last decade and a half or so, doesn't mess this up in a way that is detrimental to farmers and ranchers who are looking to continue to do good work. – [Interview 10]

And so, it's difficult to help implement the program when it's changing every four years, or the priorities of the program are changing, or the different funding targets we have are changing. And so sometimes it can be a little bit constraining on really implementing the program the way you want to when it changes every four years.” – [Interview 5]

Other constraints to learning, flexibility, and adaptability, of program processes discussed were timelines for funding allocation and inadequate communication at the state and local level formal meetings between NRCS and collaborating partners, stakeholders, and individuals. With respect to the former, a participant indicated the time between receiving funding allocation and obligating funds to address resource concerns is often short and unrealistic, leaving NRCS at the state level less time to seek input from their partners and the public in making strategic plans for using funds. With respect to communication, some participants were of the view that communication at formal meetings could be improved by NRCS at the state and local levels by being intentional about soliciting inputs from stakeholders and collaborators at meetings, listening to the opinions of these stakeholders, taking their recommendations into consideration, and providing feedback on the relevance of such inputs to program decisions. As shared by this participant:

“I would say that mostly NRCS is presenting information about their programs and isn't really seeking much input, from others. And I think other states might have state technical committee meetings that have much more input.” – [Interview 8].

Finally, the lack of time to organize information sessions for the farming community about conservation program policy and associated changes was identified as a constraint. This constraint, according to a participant, resulted in inadequate knowledge within the farmer community about the conservation program policies and the changes that may have occurred to the program, particularly at the state level. Consequently, farmer participants of the State Technical Committee who had limited knowledge and understanding about program policies rarely contributed to discussions about areas of the program that needed tweaking or adjusting to reflect broader state priority resource concerns as expressed by this interviewee:

“But you know… one of the things that I think I would wish we had time for that I find that we lack time for is to educate our producers on some of our program policies and what's coming before the State Technical Committee so that they... many times when we have producers at those meetings, they're more quiet than maybe we would want them to be just because they're not as familiar with our programs. So, there's probably a need if I'd like to do anything I'd like to educate more of our producers, so that they're as knowledgeable as our other partners on program needs and programmatic requirements and that kind of thing. Because sometimes I think they're quieter and that lack of knowledge maybe or that feeling that maybe they know what happened on their farm and they liked it-... Or in their forest but they don't feel like they can speak universally across the state naturally.” – [Interview 1]

Knowledge co-production

The analyses of the program documents and interview responses show that there is an opportunity for knowledge co-production between Congress, NRCS, and diverse actors and stakeholders with an interest in conservation with respect to Farm Bill programs, such as EQIP. At the state and local levels, knowledge generation covered key issues related to program implementation as observed in 7 CFR § 1466.2, a federal regulation that guides program administration and implementation:

“NRCS supports locally-led conservation by soliciting input from the STC and TCAC at the State Level, and the local working groups at the county, parish, or Tribal level to advise on issues relating to implementation – program priorities and criteria; priority resource concerns; BMPs to treat identified resource concerns; and recommendations for program payment rates for payment schedules” – [7 CFR § 1466.2]

Knowledge generation occurs during reviews of the program policy and implementation practices at the different stages of the program cycle to increase the likelihood of success. At the congressional level when the farm bill is being debated for reauthorization, knowledge from consultants, non-state actors, individuals, and agricultural stakeholders based on their expertise is solicited to improve understanding of agri-environmental problems of priority, and evaluate the environmental and socio-economic impact of past approaches for addressing the priority problems as observed and experienced across the nation by the public such as program target users, conservation stakeholders, and state and non-state conservation actors. For instance, some non-state actors encourage farmers to share information with their members of congress regarding improvements they would like to see in a new farm bill with respect to resource concern priorities, funding allocations, and eligibility requirements, among others. In the same vein, the NRCS at the federal level will engage with Congress through the Senate and House Agriculture Committee about different knowledge and information that has been collated about the farm bill programs through their partners and other stakeholders and agree on what can be achieved with the new farm bill based on the authorities and the financial resources afforded to the agency by congress.

Participants indicated that at the State level, review of the program occurs through formal avenues including the State Technical Committee and Sub-committees and the Local Work Group meetings that occur at the district and/or county levels. At the committee and work group meetings, participants are encouraged to share their knowledge and observations about the program administration and implementation practices and outcomes. Although participation in the committee meetings is opened to any individual and or organization with interest in conservation, it was evident that “many of the members are generally a lot of government and non-government organizations that come together” – [Interview 1] to participate in the State Technical Committee and Sub-committees as well as the Local work group meetings.

There are other informal opportunities like office visits, phone calls, etc. where other state actors, non-state actors, and agricultural stakeholders can engage with the NRCS in sharing information and knowledge about program implementation. Through these avenues, knowledge of context-specific resource concerns was identified and shared, input on program eligibility requirements based on local geological and socio-economic conditions was shared, partnerships were formed, and funding from non-state actors and agricultural stakeholder organizations secured to partly support conservation efforts as reported by some participants.

Generally, there was agreement among some participants that opportunities for knowledge and information sharing from diverse actors and stakeholders were good for conservation program planning and implementation processes, and increased stakeholders’ willingness to participate in setting conservation priorities. A study participant expresses these sentiments by saying:

“… We value their input. They, unfortunately, at times they don't... Well, they do not have any bottom-line decision making on what programs are going to address, what concerns or how much funding, but we value their input based on their expertise, their knowledge, and the fields that they represent, their organizations or conservation districts they come to. We value, greatly, their input. Their decisions that can help us, partner with us on various EQIP product programs… But yeah, they don't have a bottom line to say on what gets funded, who does what from our point of view, but we do value their input in helping us make these decisions and make suggestions, recommendations, things that maybe we don't think about. And we're encouraged and required to go to them.” – [Interview 12]

Despite these efforts at knowledge co-production, some participants believed not all organizations or agricultural stakeholders could fully participate in the knowledge generation process. At the national level, a participant opined that diverse stakeholders who face constraints with respect to membership numbers and funding to pay for non-state actors to advocate for their needs and interest during farm bill review may not have their voices heard in Congress. Another participant opined that not all new knowledge obtained during the committee and work group meetings are incorporated into program decision making at the state and local levels. This observation was attributed to the lack of understanding about the policies and regulations that guide program decision making and implementation at these levels among some participants. At both the state and local levels of program administration and implementation, inadequate diversity among non-state actor and conservation stakeholder participants was identified as a challenge to knowledge co-production.

Actors and their roles

The involvement of diverse actors is important for the effective planning and implementation of EQIP to address the negative environmental externalities resulting from agricultural activities from working farmlands. From the document analysis, it was evident that the active involvement of other state actors, non-state actors, and other relevant stakeholders interested in improving the environmental performance of agriculture was strongly encouraged. These actors ranged from federal or state agencies, Indian tribes, conservation districts, public or private non-profit organizations, farm commodity organizations and associations, individual farmers, watershed groups, as well as any private individual with an interest in conservation activities related to agricultural production. Participation of diverse actors is perceived as “an integral part of planning or major decision-making process which provides opportunities for the public to be involved with NRCS in an interchange of data and ideas” (General Manual Title 400, Public participation).

The role of diverse actors is clearly defined and can broadly be categorized into two. The first role involves the actors serving as advisors to the NRCS and Congress on Farm Bill program issues. Key among this advisory role includes recommending priority resource concerns that are worth addressing through the EQIP, best management practices (BMPs) for addressing the resource concerns, ranking criteria for selecting farmers for program funding, and payments rates for BMPs supported by EQIP based on needs of farmers and the federal, state, and the local area. At the Congressional level, some of the non-state actors engage in lobbying on behalf of farmers and provide consultancy service to members of congress in the Agriculture Committee upon request during the planning and development of a new Farm Bill. One interview participant explains:

“Our organization has become a well-known conservation group that legislators can turn to if they have questions about policy wording and bills, and they regularly call on us to see where we stand on something if they want to decide how they need to vote.” – [Interview 3].

At the Federal level, the diverse actors provide public comments on the interim Farm Bill to the NRCS during procedures to finalize a newly authorized Farm Bill when advertised in the Federal register. NRCS additionally holds listening to sessions with members of the public, particularly minority groups in select states to solicit inputs from community members and provide informal avenues such as face-to-face meetings with NRCS national office leaders for non-state actors and conservation stakeholders to share their recommendations about the programs. At the state level, the actors play this advisory role through their participation in State Technical Advisory Committee as well as the local workgroup meetings. NRCS encourages the performance of the advisory role by non-state actors and other stakeholders by organizing public meetings, and seminars, as well as “using a variety of techniques to solicit and encourage engagement of the diverse actors with a wide variety of viewpoints” – (General Manual Title 400 Public Participation Coordination).

The second role involves the state and non-state agencies assisting the NRCS at the state level to administer and implement EQIP. These partner agencies bridge the gap between NRCS and the farm community in the provision of services to potential program participants in areas of technical and financial assistance as well as conducting program outreach to farmers through collaborative partnerships. As indicated in the 7 CFR § 1466.2:

“NRCS my enter into agreements with other Federal or State Agencies, Indian Tribes, conservation district, units of local government, public or private organizations, acequias, and individuals to assist with the program administration/implementation.”

These partnership arrangements enable the NRCS to achieve greater conservation outcomes by working with these agencies compared to if they were working alone. For instance, there are limitations on the financial support NRCS provides to potential EQIP participants due to institutional policies that guide program administration and implementation. The partnerships with diverse conservation agencies often provide financial support that lessens the financial “burden” that farmers must bear in investing in conversation as explained by this interview participant:

“Let us just say a local county conservation district, they are a local government entity, but they are a big help in helping us reach out to the local communities. So, good outcomes from this organization or these partnerships is, we work together with these applicants that we receive. Sometimes we assist each other with the workload, surveying, planning, design, implementation, all takes individuals to be part of that big process, … they help a project come about in a manner that we are able to then move forward. If it is a large project and we cannot cover the full cost because of our payment rates, they can come alongside of us, …to help us ease the pain, the financial burden, … to the landowner or the farmer. These projects, some of them, where you have major nutrient resource concerns, could be not hundreds of thousands, but millions of dollars. And when we have EQIP contract payment limitation of $450,000, that is 450,000 that is established in the farm bill.” – [Interview 12]

It was evident during the interviews and document analysis that decision-making authority with respect to program administration and implementation is exclusive to the NRCS at the three levels depending on the issue at stake. Although, the other state and non-state agencies play crucial roles in EQIP program planning and implementation, they have no decision-making and enforcement powers.

Challenges to collaboration and partnerships between NRCS and state and non-state agencies in addressing environmental issues through EQIP were identified during the interviews at the state and local levels. Some participants expressed that sometimes there are disagreements and conflicts between the collaborating actors on various aspects of program administration and implementation. They indicated that disagreements would result from the wide and diverse perspectives, interests, and philosophies that the different collaborating actors bring to the process. While disagreements may arise, often the partners are able to reach a consensus to move the process forward. A few participants expressed situations where conflicts between NRCS and collaborating agencies have not been resolved, lingering on for years and unduly affecting collaboration. An interview participant expresses this sentiment:

“And I feel like it seems as though just for as an outsider that there's perhaps different perspectives or different priorities, and a different philosophy too mainly. I think it is a deep, long historical conflict, and it probably ... It is something that has been many, many, many years in the making. And it is probably not unique just to Pennsylvania. I imagine it is something that is nationwide. Just that county conservation districts do things one way and then NRCS does it another way. And sometimes they collaborate, and sometimes they just do their own thing.”- [Interview 6]