Final report for GNE21-253

Project Information

Problem and solution pursued: Climate change is challenging food production in the NE US, and we need to design and facilitate educational programming to support growers. We do not however have a complete understanding of what types of training components are most effective in this regard, and in particular we are missing longer-term data about the impacts for participants over time. This project used a SARE-PDP funded project, ‘The Northeast Climate Adaptation Fellowship: Vegetable and Small Fruit Program’ (CAF), to explore longer-term outcomes, and in particular a) study the degree to which peer-to-peer programming influenced communities of growers and agricultural advisors (AAs), and b) see if changes in knowledge translate into sustainable practice adoption, and whether these practices are employed continually, modified, or dropped in particular farm contexts.

Research approach: This project used a combination of 1) surveys with a cohort of program participants over a four year period, 2) in-depth interviews with a selection of participants over a two-year period, 3) in-depth on-farm interviews with four case study farmer participants, and 4) social network analysis with interviewees to describe how they exchange climate adaptation-related information and advice outside of the CAF program.

Research conclusions:

- The program did have positive influences on participants, including: a) increased specific and applied knowledge related to climate science and adaptation for fruit and vegetable growing in the NE US, b) increased skills in on-farm research and collaboration c) increased skills in communicating about climate change and adaptation with different audiences, and increased energy to communicate more frequently and with new groups of people and d) The participating farmers and advisors both used this the knowledge and skills to make changes to their work, and continue to do so two years after the program.

- Farmer fellows are making many iterative changes to adapt to new climate challenges

- The combination of all three components of the educational model were important

- The peer-to-peer element was important in this program. However, the research shows that peer-to-peer is more nuanced: fellows identify peers as those that they have a reciprocal and respectful relationship with. For farmers that includes not only other peer farmers, but others in their network as well.

- The information, ideas and energy did “ripple” out. What appears to be most important is not information on particular adaptation practices, but instead a) a collective energy and communication around the issue being important and knowledge that others are working on it (collective efficacy), b) an understanding of what the specific challenges are going to be in the NE so that both advisors and farmers can better orient their planning c) accountability - participants share that they do better if they have accountability to pursue adaptation goals that they may otherwise put aside.

Impact for the agricultural community and unexpected outcomes: The results of this project are being used currently, through the NIFA-funded Climate Adaptation and Mitigation Fellowship (CAMF) program. The results will continue to be used to inform the design of future educational programming around agricultural climate adaptation and mitigation. This should lead to further economic, environmental and social benefits for farmers. Unexpected outcomes include the way in which both farmers and advisors source advice from “peers”, and how not only sharing a professional relationship is important, but how other characteristics of the relationship such as reciprocity and respect are equally if not more important. The motivation that fellows drew from the CAF community of practice was also somewhat unexpected, especially since group activities were primarily virtual, however the knowledge that others are passionate about climate change adaptation work proved to be powerful.

- Track AA Fellow changes: Track and describe how AA Fellows integrate climate adaptation concepts into their programming over the two years post program completion. Record actions they take both as a direct result of participation in CAF, as well as actions they would have undertaken without CAF. (This will allow me to estimate CAF's additionality, or the proportion of climate-related activities that can be attributed to CAF participation.)

- Track Farmer Fellow changes: Measure the progression of Farmer Fellows’ climate adaptation knowledge, confidence and further outreach efforts to peers over the two years post program completion. (Record changes due to CAF and not due to CAF to estimate CAF’s additionality, as in Obj.1.)

- Track on-farm changes: Observe and document Farmer Fellows’ adoption and use of CAF-inspired climate adaptation or mitigation practices on their farms, with particular attention to changes in practice use (tweaking), mal-adoption, or abandonment of practices.

- Map outreach and knowledge spread: Map and describe how Fellows’ outreach efforts reached and influenced additional contacts, by following the spread of concepts and practices through farmer-advisor networks. Fellows are required to do 3-5 outreach activities to other farmers as part of the CAF program. These activities can be in the form of writing (e.g. newsletter articles, blog posts), presentations to groups/conferences, or hosting farm visits. These will be documented during CAF and then integrated into network maps as part of this proposal. Fellows may also choose to do further ad-hoc outreach after the official CAF program period. These efforts will also be tracked and added to the network maps over the proposal period.)

- Evaluate learning model: Using CAF as a case study, evaluate the effectiveness of peer-to-peer learning models for advisors and growers engaged in sustainable management in the Northeast, with attention to its influence on knowledge spread and practice adoption, as above, and recommendations for future programming.

The purpose of this project is to understand the degree to which peer-to-peer programming influences communities of growers and agricultural advisors (AAs), specifically those actively engaged in sustainable management. While farmer-focused professional development training often includes a peer-to-peer element, and research suggests that farmers favor learning from other farmers, efforts to document the medium- and long-term effects of this mode of education are sparse. This is often due to funding and time constraints, with many evaluation efforts limited to assessing short-term changes in knowledge and behavior change intentions. What is missed is whether these changes translate into sustainable practice adoption, and whether these practices are employed continually, modified, or dropped in particular farm contexts. By not exploring the longer term outcomes, we lose the opportunity to refine our approaches, and diminish our capacity to support sustainable agriculture systems on a broader scale.

To address this need, I propose using a SARE-PDP funded project, ‘The Northeast Climate Adaptation Fellowship: Vegetable and Small Fruit Program’ (CAF), as the context of my study. Farmers in the Northeast are facing a wide range of challenges caused by climate change, including extreme rainfall and drought, new pest pressures, and greater risks to their operations. These are predicted to increase in the coming decades, and farmers will therefore need support to match this growing challenge – to build capacity for climate adaptation planning and management. This capacity will be crucial for the achievement of NE SARE’s vision of a diversified, profitable agriculture in which farmers steward resources sustainably.

The CAF program is taking an important step towards addressing this challenge – pairing 21 fruit and vegetable growers in the Northeast with 22 professional AAs and facilitating a 12-month partnership. Pairs are required to conduct an on-farm risk assessment, a financial analysis of an adaptation or mitigation practice, and do 3-5 outreach activities. The verification plan of the CAF program runs through January 2022, culminating in the submission of final reports from the Fellows and a post-program survey. Specifically, the approved verification plan aims to capture a) changes in knowledge, b) application of knowledge, and c) confidence working on climate-related topics - all compared to the baseline data collected one year prior.

The currently funded work will give an initial snapshot of the immediate changes resulting from the CAF program. However, it does not allow for any longer-term tracking of outcomes after the program ends. To accomplish this, I propose tracking the flow of knowledge and ideas, and the use of new practices at farm-level, for a two-year period after CAF program completion. This should highlight the benefits and shortcomings of this type of education program, and show how climate-adaptation information and motivations do or do not “ripple out” beyond program participants into the broader community of Northeast farmers and AAs. I am particularly interested in the additionality of the CAF program, meaning I wish to assess whether changes are made because of the program, or if farmers would have made these changes without CAF.

Cooperators

- (Educator and Researcher)

- (Educator and Researcher)

Research

2024 Update:

The research plan, including what is described below in the Materials and Methods section, was completed largely according to plan. The following small changes were made along the way:

- Interviews were carried out as planned, with the exception that one of the eight farmers in the group selected for interviews was not available the second year (2024). So I carried out 8 farmer fellow interviews in the first year, and 7 in the second year. The 7 advisor fellows were all available for both rounds of interviews.

- Research interviews were transcribed by Production Transcripts, a professional transcription service. They unfortunately went out of business in the fall of 2024 (after this project was completed).

- Interview transcripts were coded and analyzed using qualitative research software. First year interviews were coded in NVivo. Second year interviews were coded in Dedoose. All first year data and coding was transferred between the two programs. Coding was done by the graduate student, Sara, along with a second coder, a post-doctoral researcher, Janica Anderzen. The two decided to switch software in order to be able to use the collaborative coding features of Dedoose, and because Dedoose allows you to input survey data along with interview data.

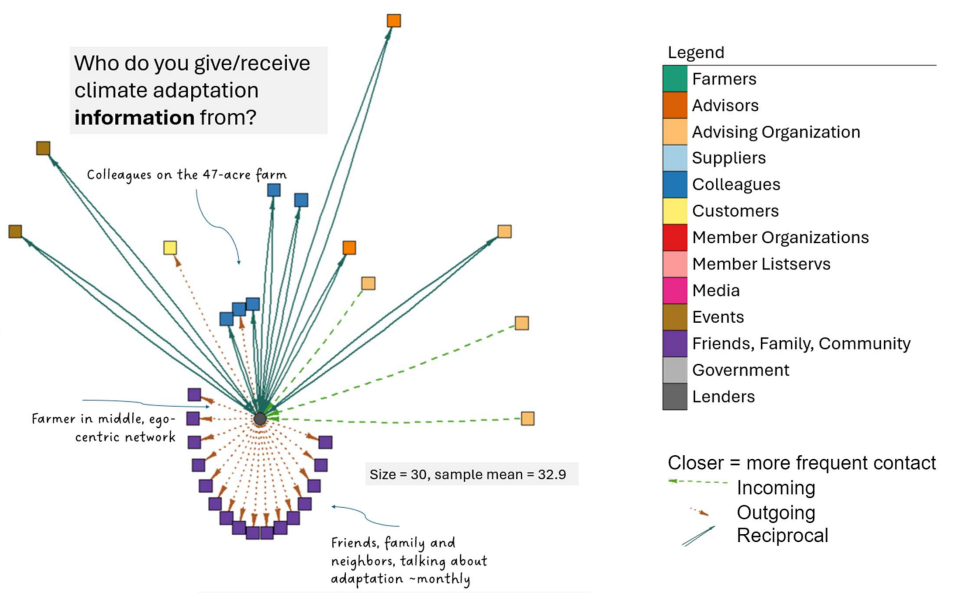

- The SNA analysis plan was refined as I learned more about SNA options. Because the data that was collected was "ego-centric", or showed the network for individual participants, I did not focus on metrics such as centrality or presence of subgroups. Instead was emerged as the most practical areas to look at were 1) how fellows were drawing on their networks for their adaptation work and what types of connections they were using, in which ways, and 2) differences across the full groups of interviews - in particular size of networks, categories of connections, and types of relations (one-way vs reciprocal), and how the interviews "rated" those connections in terms of usefullness.

on-farm interview 2022

This research uses the CAF program, including the pre-existing CAF verification plan, as a case study to answer bigger questions about peer-to-peer learning in farmer-advisor networks. The CAF verification approach captures changes in Fellows knowledge about climate change, confidence in integrating climate change into their work, as well as Fellows’ intentions for applying knowledge gained through the program in their future farm management or technical assistance programs. My research proposal extends the established evaluation period by 23 months (extending the total assessment period to 3-years) and adds significant rigor. This will lead to a deeper and more meaningful assessment of peer-to-peer, network based outreach education.

With the additional mixed-methods research in this proposal, it will be possible to move beyond looking at intentions and observe individual’s behavior. I can also explore how generic adaptations (e.g. use more cover crops) are tailored to specific farm contexts, and by doing so improve our understanding of the potential benefits and limitations of these practices.

To meet each objective, I propose using the following methods:

Data Collection Methods:

- In-depth review of CAF materials (Objectives 1 - 5)

Some of these materials (bullets a-e, below) will be reviewed as part of the CAF verification plan. I will use the output of this review to serve as both a baseline to evaluate later change, as well as guide farm visits, in-depth interviews and follow-up surveys. Items described in bullets f,g, (below) are not included in the original CAF verification plan, but are summarized here to describe the baseline my research will build upon.

Baseline CAF verification materials:

a. Fellow’s application survey (July - Sept 2020) - Current farm practices, where the farmer gets his/her information or advice, how often they already talk about climate change related topics, their climate change beliefs, and perceived farm risks.

b. Post-workshop evaluations (January 2021 and January 2022) - The CAF program is bookended by two all-participant workshops in January 2021 and January 2022. Evaluations include responses from Fellows on climate change knowledge/confidence, changes in knowledge, evaluation of the workshop content, intention to make changes on the farm, and requests for future content.

c. Fellows’ work plans (submitted Feb 2022) - Including an on-farm risk assessment, financial analysis of an adaptation or mitigation practice, outreach activities, and other optional activities chosen by Fellows.

d. Outreach Log: (April 2021 - January 2022) - Documentation of outreach completed during the program time period, including mode of outreach, number of other farmers reached, and topics.

e. Fellow’s final reports (Jan 2022) - Results of on-farm assessment and analysis, farm trials, outreach products, and new contacts reached. Report template also asks Fellows to share their intentions for applying knowledge gained through the program in their future farm management or technical assistance programs.

Additional materials to be reviewed through this project:

f. Workshop notes and discussion logs (January 2021 and January 2022) - Agendas, personal notes taken during the workshops, chat logs, as well as CAF listserv archives.

g. Educator meetings notes (December 2020-January 2022) The Educator team is a group of 7 AAs, most of whom were involved in the development of the CAF curriculum. This group includes 5 University staff, a representative from the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association, and the USDA NE Climate Hub, who inform workshop design and support Fellow pairs through the 12-month process.

The analysis of the items described above will provide descriptive information on the Fellows and their experiences in the program as they stand in January 2022 - including differences within the group such as the magnitude of change in knowledge or confidence, future intentions, and satisfaction with the program. The review and resulting baseline will allow me to track how Fellows progress over the following 2-years and identify any change based on these results.

2) Cross-sectional surveys: (Objectives 1 - 5)

I will design and send out a survey to all CAF Fellows to capture changes in outcomes. This survey will be sent twice: 1 year post CAF (January 2023) and 2 years post CAF (January 2024).

These follow-up surveys will include some of the same questions as the three CAF surveys included in the established verification plan (application period, post-January 2021 workshop, post-final January 2022 workshop) so that I can follow changes in knowledge and perception over this entire period. I will also add new questions related to the Fellows’ experiences with their farm practices and any further outreach they have done.

3) In-depth semi-structured interviews: (Objectives 1 - 5)

I plan to conduct in-depth interviews with 15 Fellows in the Fall of 2022 and Fall of 2023. Through these conversations, I will document the following:

- Longer-term perception of educational programing (all Fellows): I will capture Fellow’s perceptions of the CAF program as it fits in with their other professional development experiences, after they have had time to see the results of new practices on their farms (Farmer Fellows) or results of their new programing (AA Fellows). I will:

- Document their experience with other professional development programs, and compare their experiences with CAF to other peer-to-peer education, advising or networking activities.

- Ask which specific aspects of the CAF educational programming have provided lasting changes for them (CAF curriculum, 1-1 support through AA-farmer pairing, CoP, and outreach).

- Probe for deeper explanations to these responses to add to the results from the cross-sectional surveys and triangulate findings.

- On-farm changes (Farmer Fellows): I will ask for information about any CAF-attributed farm trials, demonstrations or changes on their farm. I will document what they did, the results of their efforts, lessons they learned from the experience, and their plans for the future.

- Programming changes (AA Fellows): I will ask for information about any new information or concepts they have integrated into their programming. I will document what they added to existing programs or if they established new programs, the results of these changes, what they learned, and their plans for the future.

- Communication changes (all Fellows): I will ask Fellows to report on outreach activities they did because of CAF. Specifically, I will seek to understand if their communication about climate change and agriculture has changed because of CAF. I will ask about who they discuss climate-related topics with, what they talk about, and whether they have noticed any colleagues changing their practices or programming, perhaps because of their interactions.

4) Farm visits and case studies (in-person or video if necessary): (Objectives 2 -5)

Farm visits and in-depth conversations with four farmers will be used to further document changes the Farmer Fellows have made to their farming practices, and when possible, the results of those changes. Discussions at the farm-level will also provide context, including attributes of the environment and climate of the farm, the full staff team, and their specific risks and challenges. Visits can give a valuable visual on the crops and chosen management practices. I will document these visits using notes, photography, and video, with the farmers’ permission.

It will not be possible to visit every Farmer Fellow, and so I propose choosing a subset of farmers to visit and highlight. These case studies will include a deeper look into the story of a specific farm and farmer(s), and how the CAF program has impacted their farm management and communication related to climate change. Farmers will be selected with an aim to highlight diverse experiences - looking for a mix in geographic location, type of farm, gender/age/experience farming, as well as reported experience with the CAF program.

5) Collection of Fellows’ feedback: I will report my findings to the CAF Fellows in March of 2023 and March 2024, and gather their feedback as a form of data triangulation. Their responses will be used in 2023 to adapt remaining research methods as appropriate (survey and interview questions), and in 2024 to inform conclusions.

Analysis:

1) Outreach tracking and network mapping: (Objectives 4 and 5)

One of the key attributes of the CAF program is the requirement of Fellows to share what they have learned with their peers and the broader agricultural community. This can be in the form of in-person farm visits or group conversations, conference presentations, or written contributions to newsletters, blogs, etc. Each pair of Fellows are required to complete 3-5 outreach activities as part of the CAF program, and I anticipate that many may continue to share their learning after the official end of that program. I will track and map the outreach of Fellows over a 3-year period, starting in February 2021, through February 2024. I will track the mode of outreach, topic, and audience reached to create a series of maps of the spread of CAF-attributed knowledge and ideas.

Through the proposal period, I will track:

- In-person and other informal outreach conducted by the Fellows: I will utilize all contact points with Fellows (farm visits, in-depth interviews and surveys) to ask about any informal outreach that Fellows can recall and who they reached (to the best of their knowledge). I will follow-up by phone or email with as many of those new contacts as possible, to ask about how the information shared was perceived or used.

- Written, published and formal presentation outreach: I will attempt to follow available data such as website hits, social media views, newsletter or journal readership counts, and audience attendance at conferences. This will require coordination with publishers, conference organizers, and website managers. I will follow-up by phone or email with readers or audience members when possible, to ask about how the information shared was perceived or used.

Through this outreach mapping, I will record key descriptive attributes of the connections, as supported in the literature on Social Network Analysis (SNA) (Knoke and Yang 2020): a) frequency of outreach, b) duration (before or after CAF, length of contact period), and c) substance of outreach. This will allow me to create a series of ‘ego-centric’ network maps, showing all of the connections made by a Fellow related to CAF ideas. These maps can be made to show: a) network change - pre-existing and new connections of each Fellow, b) temporal change - how networks evolved and ideas spread over time, and c) spatial change - how connections evolve over a geographic area. Using this established approach, I will look at key characteristics of these new networks, including network density, centrality, presence of subgroups, homophily and bonding and bridging ties (Bourne at al. 2017). Examples of network maps created using SNA are included in the supporting documents as examples.

Examples of SNA network maps;supplementary material

2) Data Analysis (Objectives 1 - 5)

Document review will be conducted through NVivo, a widely used qualitative coding software. Working with my advisor, I will develop a code book based on the project research questions. Themes from this review will be used to triangulate data collected in surveys and interviews (see below) and will be described in a narrative report.

Survey data will be analyzed using R (for quantitative results) and NVivo (for open-ended qualitative results). In addition to running descriptive statistics, I anticipate using R to do standard nonparametric statistical tests (e.g. Kruskal-Wallis H and related tests) to compare different groups of survey respondents (farmers and AAs) and how membership in these groups affects dependent variables described above (i.e. confidence in making decisions with climate change in mind, intentions to make changes on their farms or in programming, and the actual changes implemented). I will also use R to run SNA, using one of a variety of packages available (igraph, sna, or networks). These packages will allow me to assess network size, connectivity, and centrality. They also will allow me to create informative data visualizations.

Interviews will be transcribed and analyzed using NVivo. I will again work with my advisor to develop a qualitative codebook based on the project interview guide, assign codes, and assess pre-identified and emergent themes. With the assistance of an undergraduate research assistant, I will use a double coder approach for this portion of the analysis, an established method for reducing bias in qualitative analysis.

Works cited:

All data collection steps have now been completed, and analysis is well underway. The following results and implications can be reported:

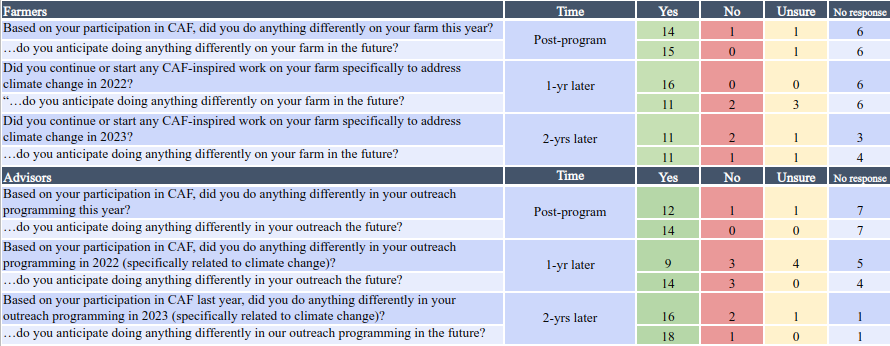

Objectives 1-3: Identify changes among CAF participants: In survey data participants shared they have made changes in their work based on participation in the program (selected responses in Table 1). No and unsure respondents explain that they were already working on adaptation, were waiting to see results, or lacked the opportunity to make a change that year.

Out of the 18 advisor fellows, 17 responded to surveys, and all 17 of these advisors stated that based on their participation in CAF, they did something different in their outreach programming specifically related to climate change. Some advisors (n=2) only implemented a change during the fellowship or directly after, while others (n=2) shared that they did so after one or two years had passed, and two others made a change during CAF, did not do anything differently in the year after, and then again made a change in 2024. Eleven advisors responded that they had done something differently due to CAF every year between 2021-2024.

Similarly to the advisor fellows, the longitudinal surveys asked farmers "Based on your participation in the CAF program, did you do anything different on your farm this year?", and then, in the following years, if they "continued or started any CAF-inspired work on their farm specifically to address climate change?" There were 18 farmer fellows who responded to the surveys, and of those, all 18 responded that they did CAF-inspired work on their farm at some point during this time period}. Thirteen farmers responded that they had done something due to CAF every year, while there were three who did so directly after the program, and two who did so after one or two years had passed.

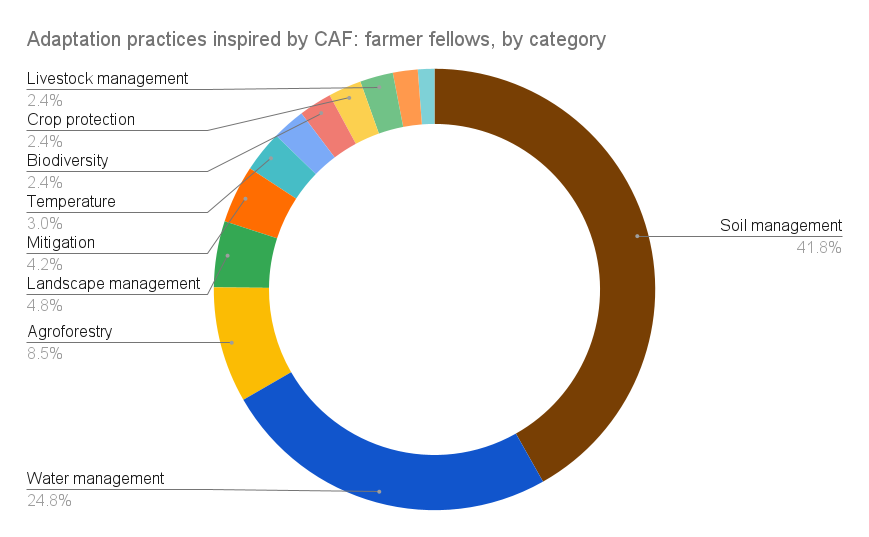

I documented a wide variety of on-farm adaptations used by growers because of their participation in CAF, with the majority focused on soil and water management.

AA fellows reported adding climate change specific outreach, adding a new climate change “lens” to ongoing programs, and feeling that the quality of their outreach had improved.

Communication: Both groups shared that they were communicating more confidently, effectively, and energetically about adaptation and mitigation. Their communication was more frequent, more specific and clear, and they were also reaching new audiences. For farmers those new audiences included customers, other farmers, and advisors. And for advisor fellow they included farmers who aren't concerned about climate change, beginning farmers, and colleagues. Both farmers and advisors also mentioned talking more to family, friends, neighbors, and the "non-farming community".

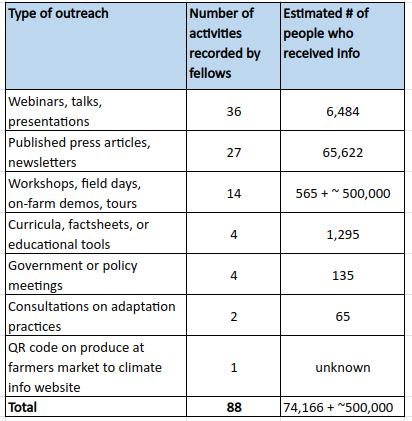

The CAF program asked all advisor-farmer pairs to share what they were learning and doing through at least three outreach methods. They were also asked to document their outreach so that we could track it. The following table shows the results of this outreach tracking, including activities starting from February 2021 through to September 2024 (8 months after the official end of the program). We know that further outreach motivated by CAF was carried out after this time period but it is not included here. The most common type of outreach conducted was webinars talks (n=36), followed by published press (n=27). It is important to note that in-person events were reduced during this time due to the ongoing Covid pandemic. Fellows recorded the number of recipients, such as audience members, attendees or readers, when known. The wide reach of press and newsletters is notable here, as is the fact that approximately 6,000 people listened to talks about adaptation given by fellows. Smaller outreach events had a contrasting advantage of allowing for more personal conversation and connection.

Outreach conducted by CAF Fellows. (Notes on recipient counts include: 1) One presentation had an estimated audience of 3,000, 2) published press counts include either page views or subscriber counts depending on what was available and subscriber counts overestimate actual readers, 3) Larger reader counts within the 65,000 include one article with 13,130 page views as of March 2023, three newspaper articles for a paper with a subscriber count of 7,100, one article for a newsletter with a subscriber count estimated at 5,000, and two articles for an Extension newsletter with a subscriber count of 2,869. 4) The on-farm demonstrations included one large farm which estimated 500,000 people visited their farm and heard about their adaptation work through either a tour, class, museum or farm to table event, and this is listed separately due to the size 4) For activities in which the fellow did not fill in the number of recipients, a very conservative estimate was made)

On-farm changes: Responses reveal that “adoption” is an iterative and continuous process. Fellows undertook a range of adoption related actions, including: increased awareness of, or attentiveness to climate challenges or adaptation options; beginning of new practices, systems, or routines; intentional expansion or reduction of previously used practices or systems; motivation to follow through in use of a practice or routine; initiation of new working relationships, applying for new types of funding; and conducting more public outreach.

Data was analyzed to quantify the types of actions related to climate adaptation by both farmers and advisors. The word cloud below shows these actions, with the size relative to the number of times this action was mentioned in surveys and interviews between 2021-2024. For reference, the most prevalent action was “expand”, which was mentioned 54 times.

One takeaway from this, is that in the context of agricultural climate adaptation, the behavior to focus on for farmers is a sustained engagement with the process of climate-change oriented experimentation. Sustained engagement, rather than the trialing or adoption of a single practice or even set of practices, is crucial. This is due to the wide range and intermittent yet recurring nature of climate stresses, which persist on top of a farm's ongoing demands around production, finances, markets, and community. In parallel to this farmer behavior, the desired behavior for agricultural advisors is the support for the farmer climate-change oriented experimentation process. Advisors need to tailor their support for the process, which is inherently incremental and iterative. This means that it spans multiple agricultural seasons rather than being a one-time behavior change

One takeaway from this, is that in the context of agricultural climate adaptation, the behavior to focus on for farmers is a sustained engagement with the process of climate-change oriented experimentation. Sustained engagement, rather than the trialing or adoption of a single practice or even set of practices, is crucial. This is due to the wide range and intermittent yet recurring nature of climate stresses, which persist on top of a farm's ongoing demands around production, finances, markets, and community. In parallel to this farmer behavior, the desired behavior for agricultural advisors is the support for the farmer climate-change oriented experimentation process. Advisors need to tailor their support for the process, which is inherently incremental and iterative. This means that it spans multiple agricultural seasons rather than being a one-time behavior change

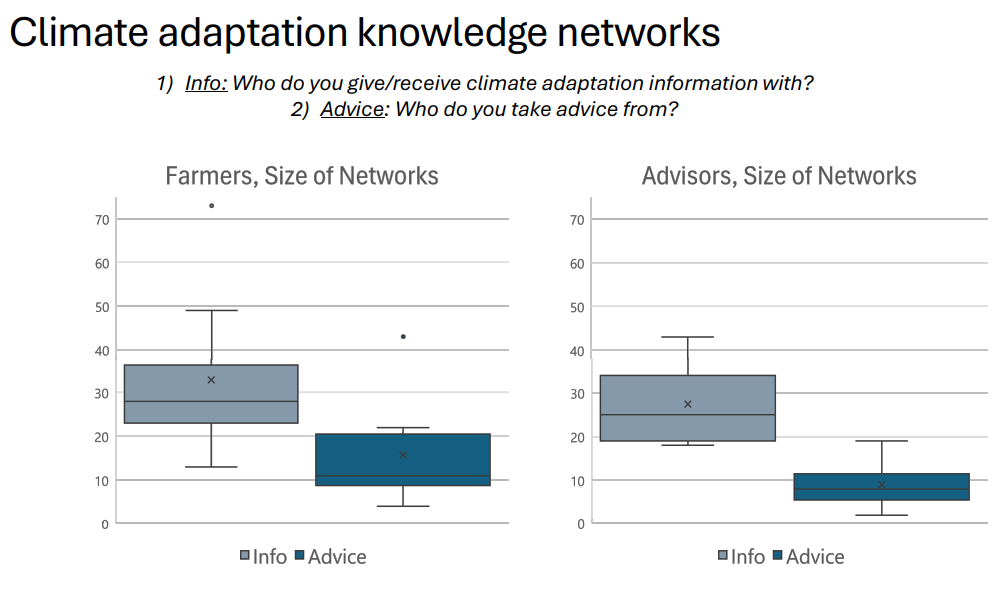

Objective 4: Map climate adaptation social networks: Results show that, contrary to expectations, there is no evidence of specific on-farm climate adaptation practices (e.g., cover cropping; reduced tillage) spreading either within the CAF cohort or in broader social networks. Instead, likely due to the unique nature of each farm and advising role, fellows are discussing broader strategies for adaptation, such as using soil management practices to increase resilience to erratic rainfall. SNA results also show a spread amongst farmers of climate change-oriented experimentation, and for advisors, climate change-oriented outreach. The changes appear to be supported through repetition from multiple sources, rather than triggered by single connections. Visuals below show first, an example of a farmer's climate adaptation social network, second, data from the full group of interviewees, showing the range in size of farmer and advisor adaptation networks, and third, who interviews identified as their strongest category for information, advice and support.

These charts show how farmers and advisors are sourcing information, advice and support not only from the typical sources that one may have predicted, but how they are also drawing on media, family, friends and community.

The social network data from farmers and advisors also points to an interesting finding regarding peer-to-peer learning. When fellows were asked who they shared climate adaptation information with, who they took advice from and who they received support from - it became clear that they favored connections which were reciprocal - or those that were a two-way exchange. Farmers did often name other farmers as reciprocal information sources, 77% were other “peer” farmers. But they also had important reciprocal relations with advising organizations, advisors, and friends, family and neighbors. Advisor fellows, on the other hand, noted that about half of their reciprocal climate adaptation advice was coming from other advisor peers, but the other half was coming primarily from farmers. In addition, when asked, both farmers and advisor fellows were very specific about who they considered to be a peer - not all other farmers, or all other advisors were peers. Peers, instead, were those that they had a relationship with, a shared approach, had respect for each other's knowledge and skills, and believed their advice to be unbiased, specific and accessible. Therefore - a finding from this research is that who a farmer considers a "peer" is nuanced and specific. Peers for farmers include other “peer” farmers, but not all farmers, and will also include professional advisors, friends and family members.

The final 2024 social network has not been fully analyzed yet. However, results to date do show that the attributes of farmers’ and advisors’ social networks can be influential to their efforts with climate adaptation. For example, networks which are larger and more diverse support that person to be better informed. As one farmer said: “ If all I hear is the same thing from the same group of people, I'm never going to learn. Right? So, I know I need to be interacting with people from all different perspectives.” (Farmer fellow).

Networks which include others which are focused on agricultural climate adaptation support the person to feel more confident. As explained by one advisor: “The ability to get together with other people who are focused on this and to share ideas is always important, and kind of powerful.” (Advisor fellow) And finally, the data is showing how important accountability is for both farmers and advisors to continue their work on adaptations. Both of these groups are busy, and can easily get pulled into the day-day urgent demands of their jobs. In order to sustain a focus on long-term planning for climate risks, it is helpful for them to have individuals or groups in their network that hold them accountable, either by specifically checking in about their goals, or by just raising the topic in conversation so that it moves up the agenda.

Objective 5: Evaluate learning model:

Data from this project shows that the combination of educational components used in the CAF program was important for achieving the successful outcomes. More specifically, the workshop and curriculum supported fellows with increased regional climate science knowledge relevant to agriculture, and also gave them more examples of climate challenges, adaptation options and possible solutions. The advisor-farmer paired activities helped farmers to have increased data on the effectiveness of a specific practice, and also helped to gain skills in the process of on-farm research. Many participating advisors also improved their understanding of farmer realities. The outreach that the pairs were required to do also supported both increased confidence in communication skills for some, and contributed to an overall increase in discussion and awareness of the topic in the broader regional agricultural community. Finally, the fact that the CAF program took a Community of Practice (CoP) approach, in which the full cohort was together (virtually) for both workshops and also could communicate via email throughout the year helped to increase the amount of examples of adaptation that were exchanged within the group. It also led to an increase in what is called “collective efficacy”, or, the idea that together a community can make a difference. Fellows shared that being part of a cohort of people in their regional agricultural community who were similarly interested in learning and experimenting around climate adaptation was energizing. When participants described this experience they used words such as "inspire", "motivation", "hope", "powerful", "more doable", and "reduced overwhelm". This increased collective efficacy led many to either start or expand their adaptation activities, and also to increase their communication on this topic.

While any one of these components would have led to some positive outcomes, it appears that the combination of a) gaining new knowledge and skills, with b) the opportunity to apply these ideas on an individualized farm-setting over the course of a year, and c) the push to communicate what they were learning with others, and d) being part of a group with shared objectives led to more sustained and individually-relevant behavior changes for participants. The fact that the program took place for a full-year was important, many of the outcomes took time to build. A number of participants noted that they wished it had been longer, since on-farm adaptation planning and trialing can often require more than one season. The timing of this fellowship, from 2021-2022 also meant that all of the large-group activities took place virtually due to Covid safety measures. While fellows still reported that they did benefit from the virtual group experience and felt connected in some way, many said that they think the community of practice would have been more powerful and exciting if the workshops had taken place in person.

I will be presenting data from this project to the CAF fellows who are attending the New England Fruit and Vegetable Conference in-person in mid-December of this year, just after the deadline for this report. The plan is to show the key results, and to ask this group of practitioners what recommendations they would make for future programming based on what they see. I am excited to see how that activity goes. In the meantime, I have included a few recommendations that I see in the final section below.

The key conclusions are as follows:

- The program did have positive influences on participants, including: a) increased specific and applied knowledge related to climate science and adaptation for fruit and vegetable growing in the NE US, b) increased skills in on-farm research and collaboration c) increased skills in communicating about climate change and adaptation with different audiences, and increased energy to communicate more frequently and with new groups of people and d) The participating farmers and advisors both used this the knowledge and skills to make changes to their work, and continue to do so two years after the program.

- Sustainable practice adoption looked like sustained climate-change oriented experimentation, farmer fellows are making many iterative changes to adapt to new climate challenges

- The combination of all three components of the educational model were important, including the training curriculum delivered during workshops, the advisor-farmer pairing to carry-out specific activities in an individual farm, and the community of practice to facilitate group conversation and learning together.

- The peer-to-peer element was important in this program - both farmers and advisors reported benefiting from having those that they consider peers in the group. However, the research shows that peer-to-peer is more nuanced: fellows identify peers as those that they have a reciprocal and respectful relationship with. For farmers that includes not only other peer farmers, but others in their network as well.

- The information, ideas and energy did “ripple” out. What appears to be most important is not information on particular adaptation practices, but instead a) a collective energy and communication around the issue being important and knowledge that others are working on it (collective efficacy), b) an understanding of what the specific challenges are going to be in the NE so that both advisors and farmers can better orient their planning c) accountability - participants share that participating in this program provided accountability, and they do better if they have accountability also after the program through either continued interaction with CAFers, or within their own social network.

- Limitations of the program included a) the lack of in-person meeting, b) one year was actually too short for many fellows who wanted multiple seasons to work on a new practice, c) some participants did not feel they had enough peers in the cohort, d) the planning tools/worksheets could have been better developed e) participants need different levels of detail or focus in their climate science education, it’s hard to satisfy everyone with a single training session.

Preliminary Recommendations:

- Revise and update the climate adaptation planning templates and tools that were developed for the CAF project based on fellows’ feedback (this has already happened and will continue)

- Try to meet a broader variety of knowledge levels and learning styles by using a combination of pre-recorded and self-selecting modules, along with the live training sessions.

- Include in-person activities in climate change education programming as much as availability, logistics and budget allow.

- Aim to design climate change educational programming that is at least one-year in length.

- Include and increase the emphasis on the Community of Practice element, as this proved highly beneficial for many in this CAF cohort.

- Think carefully about who to include in farmer-to-farmer “peer” programming. Broaden the attention beyond 1:1 peer learning, and even beyond farmer groups. Think instead about the qualities identified here for what makes a “peer”, and target cohorts in which participants have the opportunity to interact with those that they share mutual respect and objectives.

- Consider allowing participants to invite one or more people from their personal social networks to join programs like this one, in particular if the program is targeting a complex behavior change like climate adaptation. Having others in their network that can support and provide accountability, because they have participated in the same program, can help to support more sustained behavior change.

Education & outreach activities and participation summary

Participation summary:

The following outreach related to this project has occurred:

- Feedback to interviewees: Each of the interviews, including the four on-farm summer interviews, and the 15 winter zoom interviews, received a write-up of the key themes identified in their first interview. I checked with the interviewees for accuracy and resonance, and for any missing ideas. All feedback shared by interviewees is being discussed and incorporated into the data.

- I presented initial findings from this research at the annual conference of the International Association for Society and Natural Resources (IASNR), which took place in June 2023 in Portland, Maine. The talk was titled: “Experimenting together: applying research to improve climate adaptation programming in agriculture”. And was presented by myself, along with one of the farmer interviewees from the project.

- I presented a poster with findings from this research at the annual conference of the Agriculture, Food and Human Values (AFHVS) society in May 2024, in Syracuse, NY. The poster was titled: “The big, big everybody”: The role of farmer and advisor networks in supporting adaptive food systems in a changing climate in the NE-US.

- I presented a talk based on findings from this research at a conference hosted by the National Wildlife Foundation, called Growing Outreach, in Madison, WI, in August 2024. The talk was called: "Reinforcement Through Community: The Role of Farmer and Advisor Social Networks in Supporting Persistent Innovation and Outreach in a Changing Climate"

- I have published two articles in peer-reviewed journals in the past year. Both of these utilize some of the initial data and themes from this research, but they are both review or commentary pieces, rather than publications sharing research results, since the research is still ongoing. However, as they are related, I will include them here:

- Delaney, S. and von Wettberg, E.J.B. (2023) Towards the next angiosperm revolution: agroecological food production as a driver for biological diversity. Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene. https://doi.org/10.1525/elementa.2022.00134

- Delaney, S. (2023) Who to call after the storm? The Challenge of Flooding due to Climate Change for Fruit and Vegetable Growers in the Northeast United States. Environment and Society 14(1). https://doi.org/10.3167/ares.2023.140105

- Two webinars in March of 2022, for the Maine Agriculture and Climate Network, titled "Adapting to Climate Change on the Farm", which featured a total of four Farmer Fellows from the CAF program. Attendees included a mix of University of Maine faculty and students and agricultural professionals.

- A workshop for the Maine Farmland Trust, coordinated by one of the advisors that participated in the CAF program, for a group of ~15 farmers, on climate adaptation and mitigation planning. This was inspired by the material from the CAF curriculum.

- Further journal publications and fact sheets to share results are planned for 2025.

- I will be hosted a meeting for CAF participants at the 2024 New England Vegetable and Fruit conference, to share findings from this research, gather the CAF fellows' feedback, and use that finalize recommendations that will appear both in my dissertation publications, as well as factsheets and blog posts.

Project Outcomes

By following fellows for two years after the CAF program, we are able to see the range of actions that they have taken as a result of participating in the program. As described in the research findings section, all 18 farmer fellows and 17 advisor fellows that responded to surveys made changes to their adaptation work due to CAF participation. These changes are helping fruit and vegetable growers in the NE US to be better prepared for the challenges of climate change. And advisors are better prepared to support them. These fellows are actively experimenting with new adaptation strategies, and the advisors in this group are actively working to support this experimentation by integrating new types of outreach and tools into their programming.

These fellows have climate adaptation knowledge networks through which they are actively discussing this new work they are doing. Using the average size of farmer networks, which is 33 connections, and the average size of advisor’s networks, which is 16 connections, we can say that the work being done by these fellows is also impacting (18*33 = 594) other individuals and groups through the CAF farmer fellows’ activity, and (17*16 = 272) other individuals and groups through the CAF advisor fellows’ activity. This is approximately 860 additional members of the NE agricultural community who are influenced by the information on climate adaptation which was produced as part of this fellowship. Because this wider group is better informed and more actively pursuing adaptation objectives, they will be better able to continue to produce vegetables and fruits in this region sustainably.

In addition, the results of this project are being used currently (through the NIFA funded Climate Adaptation and Mitigation Fellowship (CAMF)), and will continue to be used to inform the design of future educational programming around agricultural climate adaptation and mitigation. This should lead to further economic, environmental and social benefits for farmers.

We can share that two grants were applied for as a direct result of this project. One was an application to USDA-NIFA for an expansion and next round of the first Climate Adaptation Fellowship program, and that grant proposal was led by my advisor, Dr. Rachel Schattman. That proposal was successful. Because of that grant, a greatly expanded and updated version of the climate adaptation education program which this research is utilizing as a case study launched this January 2024. That is called the Climate Adaptation and Mitigation Fellowship (CAMF). Some aspects of the design of that program were built off of initial findings from this research project.

A second is a grant that a small group of CAF fellows applied for together, to SARE, which was partially inspired by the knowledge and network they gained through the CAF program. My understanding is that the proposal was awarded and is related to riparian buffers. The financial amount was not shared with me as part of the interview process.

In addition, in October 2023 I applied for a USDA-NIFA Predoctoral EWD Fellowship. I learned in the spring of 2024 that I was not selected for this fellowship. However, the work I did in preparing that proposal helped me to organize my research and project management, and also to start thinking through career options. The work I have been doing in my research, supported in part through this SARE grant, helped me to be able to effectively present my research, and propose new activities that would further my ability to be prepared for a career in the field of agricultural research or advising after I finish my degree.

My knowledge, skills and awareness related to sustainable agriculture is growing every month. The process of interviewing farmers and advisors this summer and fall was hugely educational, and I have a much more nuanced and detailed view of food production in the Northeast of the US. I can say that my appreciation for the challenges of managing a small or medium sized vegetable or fruit operation in this region has expanded, and that some of my previous ideas have been shown to be incorrect, for example the availability of appropriate insurance or other safety nets for farmers in my study group is much lower than I had expected. I am also learning about the importance of connections to farmers, both for practical advice and trouble-shooting, and also for mental well-being. Another learning area is related to how climate adaptation efforts progress over time, and the various events that can lead modifications, interruptions, or expansion of ideas and projects.

I plan to use my PhD research experience to explore next career steps after completing my degree. I hope to continue my career combining research and practice in the areas of agricultural education and extension to support farmers in climate adaptation and mitigation.

Longitudinal research: The most important insight from the research methods used is probably the benefits of extending the timeframe of program evaluation research. One key aspect of this data collection methodology is that I conducted repeat surveys and interviews over a two year timeframe. While this isn’t an extremely long time, it is a longer period than many program evaluations capture. I can see how much richer and more insightful the data is, including when I added the two-year data to the first-year data. I think the decision to do second-round interviews at both the 1-yr and 2-yr post-program time point was worth the investment.

Social network analysis: This aspect of the research was tricky to learn, and analysis is not yet fully complete, since it is a lengthy process. However, I think the additional insights gathered were also worthwhile. While SNA may not be appropriate for all farmer education program evaluations, it is a method that can reveal a much more complete view of participants' communication and influences. Any researcher interested in looking at this more deeply, in relation to the impacts of a program itself should consider using SNA.

Recording interviews: I can report that I have learned about the importance of recording equipment, and methods for using it, for the quality of recordings and transcripts. After an initial test-run on a very windy farm, as well as an issue with the microphone being in a farmer's pocket, recording methods were quickly improved! I would offer the suggestion to any researcher conducting and recording on-farm interviews to test out recording equipment in an environment similar to the farm prior to initial interviews.