Final report for GNE22-294

Project Information

As more farms in the US Northeast adopt conservation agriculture practices such as reduced tillage and cover cropping, new challenges to pest management continue to emerge, reinforcing the axiom that “no good deed goes unpunished”. Slugs, particularly the gray garden slug (Deroceras reticulatum) and the marsh slug (Deroceras leave) have emerged as prominent pests of corn and soybean under no-tillage systems in the United States. Chemical control using molluscicide baits is the most common control method. However, these baits are expensive to apply, ineffective in many field conditions, and harmful to humans and wildlife. Biological control represents an important alternative approach to slug management for growers practicing conservation agriculture. Slug-parasitic nematodes can be potent biological control agents, and one species is already being deployed in Europe. However, slug-parasitic nematodes are so far unknown and unutilized in the Eastern US. This is because there are only a few “locally” isolated strains in the United States (from the West Coast) and importation of such species is highly restricted. Through this SARE graduate fellowship, I identified six species of slug-associated nematodes in no-till corn and soybean production systems of Delaware and Maryland and determined the most effective way to rear slug associated nematodes under laboratory conditions. This represents an important step toward developing an effective and sustainable slug management strategy for grain production in the Eastern US.

In vitro rearing of nematodes has been a challenging process. To establish a working nematode rearing protocol, it took exploring more than eight different protocols proposed by different authors and institutions. Each of these attempts required trouble shooting and readjusting the recipes, as well as continuous monitoring for nematode survival. I also faced challenges with identification protocols, particularly extracting high quality DNA using existing methods. Despite these setbacks, I was able to complete the proposed research objectives and gain valuable insights into nematode rearing techniques for my ongoing research. Using the nematodes and knowledge gained through this SARE fellowship, I plan to determine how pathogenic these locally-isolated nematodes are against slugs, which could reveal pathways forward to creating biologically-based slug control strategies in the Eastern US.

Objective 1: Identify species of slug-parasitic nematodes and their prevalence in no-till corn and soybean production systems in Delaware and Maryland. This objective was fully achieved, laying the groundwork for understanding the nematode species present and their potential as biological control agents.

Objective 2: Develop reliable and effective rearing and maintenance methods for slug-parasitic nematodes to support future experimental studies on their effectiveness. While the original objective focused on immediately testing the effectiveness of the identified nematodes in controlling slugs, it however became clear that we needed to ensure that the nematodes were viable and able to survive for longer periods of time before being tested for efficacy. Bioassays on slug mortality and feeding behavior have not been conducted because we invested our time in a variety of nematode rearing approaches, which has provided the necessary foundation for future studies to evaluate their effectiveness.

The purpose of this project is to determine environmentally and ecologically sound management options for gray garden slugs and marsh slugs using locally isolated slug-parasitic nematodes, reducing dependency on chemical molluscicide baits without sacrificing pest control. Slugs, especially gray garden slugs and marsh slug, have emerged as major pests in corn and soybean production systems under conservation practices (Douglas & Tooker, 2012). Both species feed on a wide variety of cultivated and non-cultivated plants in addition to cover crop residues (Gall & Tooker, 2017). In no-till corn and soybean, slug damage is severe in the early growing season, usually when juvenile slugs feed on seeds and emerged seedlings (Dively & Patton, 2022). Severe damage has been reported when planting date aligns with slug hatch, which exposes seeds, seedlings, or young plants to a rapidly growing slug population (Douglas & Tooker, 2012).

Slug damage is associated with leaf shredding in corn and destroyed cotyledons or seedling death in soybean (Brichler, 2020). High levels of injury cause yield reduction and in some cases require replanting of entire fields (Douglas & Tooker, 2012). Damage is most prominent in young plants because older plants can outgrow slug injury (Abendroth, et al., 2009; Douglas & Tooker, 2012). The control of slugs through the use of chemical molluscicides applied in granular baits is difficult because the baits are easily thwarted by rain, have a short field lifespan, and need to be applied in close synchrony with pest activity (Henderson & Triebskornz, 2002; Castle, et al., 2017). Thus, there remains a need for effective and environmentally sound slug management strategies.

Slug-parasitic nematodes represent a powerful potential biological control agent because they inhabit the soil, actively locate cryptic hosts in their environment, and harbor symbiotic bacteria with potent molluscicide properties (Tan & Grewal, 2001). Even though the Western US (California, Oregon) has reported isolation of local strains of a slug-parasitic nematode species (Mc Donnell, De Ley, & Paine, 2018; Mc Donnell, Colton, Howe, & Denver, 2020), the Northeast has yet to isolate and record presence of any species or strains. In Europe, one slug-parasitic nematode species is already commercialized, but importation of nematodes is greatly restricted in the US (Mc Donnell, De Ley, & Paine, 2018; Mc Donnell, Colton, Howe, & Denver, 2020). Furthermore, slug-parasitic nematodes can be highly species-specific, with most control failures following from the use of unsuitable nematode strains or unfavorable environmental conditions (Rae, Robertson, & Wilson, 2009). Slug-parasitic nematodes thus represent uniquely adapted biological control agents whose efficacy must be examined and optimized within the environmental and geographical context where management is needed. This project will identify nematode species present in the US Northeast and their efficacy against the two economically important slugs in this region and represents an important step toward alleviating the apparent trade-off between conservation agriculture and effective slug management.

Cooperators

Research

Objective 1: Identify species of slug-parasitic nematodes and their prevalence in no-till corn and soybean production systems in Delaware and Maryland

Origin of slugs and nematodes

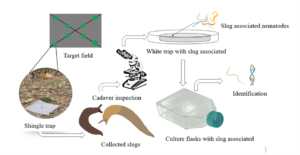

Marsh and gray garden slugs were collected from 29 different corn and soybean fields (Sites) in Delaware and Maryland, during the spring of 2022 and 2023. Slugs were collected using shingle traps and carried to the laboratory using plastic containers with perforated lids and lined with moist paper towels. Shingle traps were placed along two transects for a total of 8 traps per field, sampled weekly from March-June for a two-year period (Figure 1). In the laboratory, slugs were fed carrots and leafy vegetables, replaced daily, and the containers containing slugs were cleaned weekly and slug mortality recorded.

Figure 1. Slug-parasitic nematode isolation and identification workflow.

Isolation and identification

Slug-parasitic nematode isolation involved collecting the slug cadavers and transferring them into a white trap to encourage reproduction (Pieterse, Tiedt, Malan, & Ross, 2017). A white trap is a nematode trapping technique that uses nematodes’ attraction to water and successfully recovers the infective stages of the nematodes (Figure 1) (Orozco, Lee, & Stock, 2014). The modified white trap by Kaya and Stock (1997) consists of a petri dish, on which the host cadaver rests, placed in another larger petri dish containing water. As infective (dauer) juveniles emerge, they move to the surrounding water trap where they are harvested, and the process can be expanded to commercial production levels (Shapiro-llan & Hall, 2012). Infective juveniles were harvested within the first week of emergence, after which they were stored using culturing flasks held at temperatures between 14°C -19°C in the laboratory. The slug parasitic nematodes were identified using molecular techniques. For molecular identification, nematodes were identified by sequencing cytochrome C oxidase 1 (COI). The processes involved isolating DNA from nematodes using the worm lysis buffer. Secondly, a portion of the COI gene was PCR-amplified using combination of universal primers following (Mahmoud, et al., 2019). Third, COI amplicons were submitted for Sanger sequencing at Eurofins genomics. Lastly, resulting sequences were edited and trimmed using the Geneious software and the resulting sequences were compared to a global database of nematode COI sequences using NCBI BLAST.

Objective 2: Develop reliable and effective rearing and maintenance methods for slug-parasitic nematodes to support future experimental studies on their effectiveness

Establishing solid and liquid cultures

In vivo production and rearing slug associated nematodes is more difficult than that of entomopathogenic nematodes that require commercially produced Galleria mellonella and Tenebrio molitor. This is because slug hosts for in vivo production must be collected from the field and them maintained in the laboratory. Therefore, we decided to focus on in vitro techniques using monoxenic solid and liquid cultures using Escherichia coli OP50 bacteria.

The first step on this protocol was to establish an E. coli starter culture which is basically streaking E. coli on sterile LB agar plates and incubating them overnight at 37°C. This was followed by transferring the E. coli from a solid agar plate medium to a liquid suspension, we used a sterile loop and scraped and streaked the bacteria without picking agar. Then we immersed the loop into a 50ml liquid medium (composed of autoclaved tryptone, yeast extract and sodium chloride in distilled water) and agitated gently to release the bacteria from the loop to the liquid medium. Once the bacteria were inoculated, we placed the containers on an orbital shaker at 140rpm and set it to 37°C and incubated for 16-24 hours. The bacteria suspension was used immediately and those that could not be used were stored at 4 °C. The solid medium cultures were prepared using agar, peptone, sodium chloride, egg yolk and pig’s kidney dissolved in distilled water and autoclaved at 121°C for 30 minutes. Once the NGM was solidified it was then inoculated with a desired bacteria percent volume (2%, 3%, 4% or 10%) and incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. After the bacteria had colonized the plates a desired quantity of nematodes (5,10,15,20,50) was added to solid agar plates and checked daily for nematode growth for a period of 16 days. The liquid culture medium was prepared using a 250-ml Erlenmeyer flask with 50 ml liquid culture media (LCM) (pig’s kidney, yeast extract, egg yolk powder, sunflower oil/L water was autoclaved for 20 min at 121°C) was then inoculated with the desired bacteria percent volume and incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. We then transferred the desired quantities of nematodes into the liquid culture medium and incubated the suspension on an orbital sharker at 140 rpm and 18 °C for the rest of the experiment. Suspensions were monitored daily for nematode growth and contamination.

The experimental setup of bacterial trials involved inoculation liquid nematode growth media and solid growth media with different bacteria percent volumes 2%, 3%, 4% or 10% and then adding the same number of nematodes (10 nematodes in each) and then monitoring for their growth for a 16-day period. On the other hand, to determine the best initial nematode quantities to inoculate we picked the best performing bacteria trial, which was at 4% volume, added it to solid nematode media and then exposed it to different nematode quantities (5, 10, 15, 20 and 50) and this was monitored for a period of 10 days.

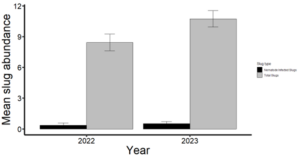

Isolation and identification of nematodes

I collected 1,030 slugs in 2022 and 1,531 slugs in 2023 from 14 corn and soybean fields in Delaware and Maryland. Among these slugs, four species were represented: leopard slug (Limax maximus), three-banded slug (Ambigolimax valentianus), marsh slug (Deroceras laeve), and gray garden slug (Deroceras reticulatum). The collected slugs in 2022 mainly consisted of marsh slugs (858), followed by gray garden slugs (121), leopard slugs (27), and three-banded slugs (24). In 2023, I only observed marsh slugs (1,043) and gray garden slugs (488). In total, only 117 of the collected slugs were parasitized by nematodes (~5%) in 2022 and 2023 (Fig. 2). Most of the infected slugs were either marsh or gray garden slugs. We identified 10 different isolates belonging to six species through DNA sequencing, namely Oscheius myriophilus, Oscheius sp, Panagrolaimus detritophagus, Cosmocercoides pulcher, Caenorhabditis briggsae, and Pristionchus pacificus.

Figure 2. Yearly trends in nematode-infected slug proportions (2022–2023).

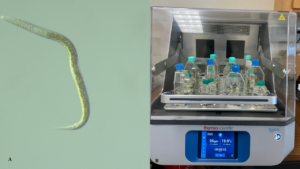

These nematodes are currently being maintained in liquid cultures in my laboratory (Fig 3).

Figure 3. A. Magnified slug parasitic nematode and B. Nematode culture flasks on an orbital shaker

Nematode rearing protocols

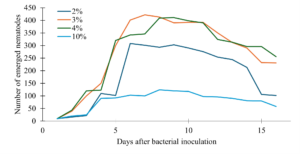

Bacteria inoculum trials (solid medium)

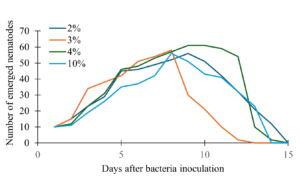

The percent volume of the bacteria inoculum that was the most effective were determined using 250 Erlenmeyer flasks containing 50ml of the growth medium inoculated with four E. coli inoculum volumes: 1%, 2%, 4% or 10%. We observed the lowest number of emerging nematodes overall when we inoculated the solid nematode growth medium with 10% volume of the bacteria inoculum (Fig. 4). There was slower growth overall, and the peak was lower compared to the other volumes of bacteria, suggesting that excessive bacteria may have some impact on nematode growth. Then the second lowest emergence volume was 1% bacteria inoculum, which peaked earlier between 5-7 days but showed a rapid decline in nematodes compared to the other volumes (Fig. 4). The 2% and 4% volumes exhibited the highest nematode emergence and slowest decline (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Effect of bacterial inoculum volume on nematode emergence over time in solid medium.

Bacteria inoculum trials (Liquid medium)

Nematode emergence increased but the numbers were low as compared to the solid medium cultures (Fig. 5). After reaching the peak, the number of nematodes declined in all treatments. Because the populations for most of these nematodes declined below sufficient volumes, and because of constant bacterial contamination, we decided not to pursue the liquid medium culture route.

Figure 5. Effect of bacterial inoculum volume on nematode emergence over time in liquid medium.

Nematode quantity trials

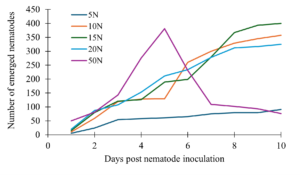

All the treatments showed a gradual increase in the number of nematodes that emerged, but we noticed that higher initial nematode volumes showed a steeper increase followed by steep decline as soon as four days post Adding 5 nematodes exhibited the lowest growth and remained low throughout. Using 10, 15 and 20 nematodes continued to increase steadily, with no decline by 10 days post nematode inoculation (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Relationship between initial nematode dose and emergence pattern in solid medium

This research provides insights towards the potential use of slug-associated nematodes in controlling slug populations in no-till corn and soybean fields in the Eastern US. We found six nematode species associated with slugs. While some of these species are possibly just using slugs as intermediate hosts, others are suspected of having parasitic potential. The study also identified both optimal bacteria volumes and ideal initial nematode densities required to increase yields. Moderate initial densities of nematodes and bacteria volumes led to the highest yields, with low bacteria volumes likely providing insufficient food and high volumes leading to resource depletion. These findings clear the way for us to test pathogenicity of these nematodes against slugs in future work. Our findings bring us a step closer to providing biologically based slug control tools into the hands of no-till corn and soybean farmers in the Eastern US.

Education & Outreach Activities and Participation Summary

Participation Summary:

I presented on slug parasitic nematodes at the SPARK symposium, a competitive program hosted by the University of Delaware graduate college to feature outstanding graduate research while providing professional communication training to selected speakers. I also won the people's choice award at this event. This year I had the opportunity of presenting parasitic nematodes at the national meeting of the Entomological Society of America, where I was awarded first place in the graduate student competition. We also presented a poster and hands on demonstration at Maryland Commodity Classic, hosted by Maryland Grain Producers Utilization Board. Lastly, we were invited to speak at the Mid-Atlantic Crop Management School, held in Ocean City, MD, regarding the management of slugs using slug associated nematodes, and emphasizing the practical applications of the research to corn and soybean farmers.

Project Outcomes

Our research project will contribute to future sustainability by identifying local parasitic nematode species that have the potential to provide control of a key early season pest without reliance on environmentally toxic molluscicides. These parasitic nematodes are naturally found in the soil and can actively locate and kill their slug hosts in the field without causing environmental contamination or imbalance. Overall, having a deeper understanding of the mollusk parasitic nematode species present in commercial agricultural fields and their pathogenicity potential is a cardinal step towards developing a sustainable mollusk management program and mollusk parasitic nematode-based control technologies

Our project's main goal has been working towards effective management of slugs within corn and soybean production systems cultivated under conservation agriculture principles (cover cropping and no-till), by increasing knowledge about the impacts of slug-parasitic nematodes on farms. We have been working on our first objective, which aims to isolate parasitic slug nematodes from the fields in the Northeastern region of the United States.

Our preliminary results have confirmed the presence of slug parasitic nematodes (albeit at low prevalence) and at least six nematode species. Two of the six species (Caenorhabditis briggsae, Panagrolaimus detritophagus) are likely non-parasitic, instead feeding on bacteria in the environment and occasionally using slugs to disperse. However, when associated with a pathogenic bacterium, C. briggsae has shown some pathogenic potential. Another species (Pristionchus pacificus) has been documented parasitizing beetles, so its emergence from a slug host is intriguing and warrants further study. Another species, Cosmocercoides pulcher, uses slugs as a paratenic host, but a similar species in this genus is slug-parasitic. The last two species (Oscheius myriophilus and Oscheius sp.) are generalist parasites known to affect insects as well as slugs.

Our understanding of nematode rearing both using solid culture media and liquid culture media has dramatically changed. Through trouble shooting and exploring different protocols, we have identified ways that these nematodes could be reared efficiently under laboratory conditions.

References

Abd-Elgawad, M. M. M., & Askary, T. H. (2020). Factors affecting success of biological agents used in controlling the plant-parasitic nematodes. Egyptian Journal of Biological Pest Control, 30, 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41938-020-00215-2

Adomaitis, M., Skujienė, G., & Račinskas, P. (2022). Reducing the Application Rate of Molluscicide Pellets for the Invasive Spanish Slug, Arion vulgaris. Insects, 13(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/insects13030301

Armsworth, C. G. (2005). The Influence of a Carabid Beetle Predator on the Behaviour and Dispersal of Slug Pests A BBSRC Studentship.

Askary, T. H., & Abd-Elgawad, M. M. (2021). Opportunities and challenges of entomopathogenic nematodes as biocontrol agents in their tripartite interactions. Egyptian Journal of Biological Pest Control, 31(1), 1-10.

Askary, T. H., Nermuthacek˜, J., Ahmad, M. J., & Ganai, M. A. (2017). Future thrusts in expanding the use of entomopathogenic and slug parasitic nematodes in agriculture. In Wallingford UK: CABI (Ed.), In Biocontrol agents: entomopathogenic and slug parasitic nematodes (pp. 620–627).

Barker, G. M. (2004). Natural enemies of terrestrial molluscs. (G. M. Barker, Ed.). CABI.

Barua, A., Williams, C. D., & Ross, J. L. (2021). A literature review of biological and bio-rational control strategies for slugs: Current research and future prospects. Insects, 12(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/insects12060541

Batalla-Carrera, L., Morton, A., & García-del-Pino, F. (2010). Efficacy of entomopathogenic nematodes against the tomato leafminer Tuta absoluta in laboratory and greenhouse conditions. BioControl, 55, 523–530. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10526-010-9284-z

Campbell, A. (2020). Better Use of Molluscicide Pellets for Improved Management of Slugs [Dissertation ]. New Castle University .

Carnaghi, M., Rae, R., de Ley, I. T., Johnston, E., Kindermann, G., Mc Donnell, R., O’Hanlon, A., Reich, I., Sheahan, J., Williams, C. D., & Gormally, M. J. (2017). Nematode associates and susceptibility of a protected slug (Geomalacus maculosus) to four biocontrol nematodes. Biocontrol Science and Technology, 27(2), 294–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/09583157.2016.1277418

Castle, G. D., Mills, G. A., Gravell, A., Jones, L., Townsend, I., Cameron, D. G., & Fones, G. R. (2017). Review of the molluscicide metaldehyde in the environment Environmental Science Environmental Science Water Research & Technology CRITICAL REVIEW Review of the molluscicide metaldehyde in the environment. Environ. Sci.: Water Res. Technol, 3, 415. https://doi.org/10.1039/c7ew00039a

Christensen, C. C., Cowie, R. H., Yeung, N. W., & Hayes, K. A. (2021). Biological Control of Pest Non-Marine Molluscs: A Pacific Perspective on Risks to Non-Target Organisms. Insects, 12, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects

Cowie, R. H., Ré, C., Fontaine, B. B., & Bouchet, P. (2017). Measuring the Sixth Extinction: what do mollusks tell us? The Nautilus, 131(1), 3–41.

Cowie, R., Rundell, R., & Yeung, N. (2017). Samoan Land Snails and Slugs-An Identification Guide (No. 2017). Lulu. com.

Crowl, T. A., Crist, T. O., Parmenter, R. R., Belovsky, G., & Lugo, A. E. (2008). The spread of invasive species and infectiousdisease as drivers of ecosystem change. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment , 6(5), 238–246. https://doi.org/10.1890/070151

de Ley, I. T., Holovachov, O., McDonnell, R. J., Bert, W., Paine, T. D., & de Ley, P. (2016). Description of Phasmarhabditis californica n. sp. and first report of P. papillosa (Nematoda: Rhabditidae) from invasive slugs in the USA. Nematology, 18(2), 175–193. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685411-00002952

Deguine, J.-P., Aubertot, J.-N., Flor, R. J., Lescourret, F., Wyckhuys, K. A. G., & Ratnadass, A. (2021). Integrated pest management: good intentions, hard realities. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 41(38). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-021-00689-w/Published

Dively, G. P., & Patton, T. (2022). An Evaluation of Cultural and Chemical Control Practices to Reduce Slug Damage in No-till Corn. Insects , 13, 277. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects13030277

Divya, K., & Sankar, M. (2009a). Entomopathogenic nematodes in pest management. Indian Journal of Science and Technology, 2(7). https://doi.org/10.17485/ijst/2009/v2i7/29499

Donnell, R. M., de Ley, I., & Paine, T. D. (2018). Biocontrol Science and Technology Susceptibility of neonate Lissachatina fulica (Achatinidae: Mollusca) to a US strain of the nematode Phasmarhabditis hermaphrodita (Rhabditidae: Nematoda). Biocontrol Science and Technology, 28(11), 1091–1095. https://doi.org/10.1080/09583157.2018.1514586

Douglas, M. R. (2012). The influence of farming practices on slugs and their predators in reduced-tillage field crops in Pennsylvania.

Douglas, M. R., & Tooker, J. F. (2012). Slug (Mollusca: Agriolimacidae, Arionidae) ecology and management in no-till field crops, with an emphasis on the mid-Atlantic region. Journal of Integrated Pest Management, 3(1), C1-C9.

Douglas, M. R., & Tooker, J. F. (2012b). Slug (Mollusca: Agriolimacidae, Arionidae) ecology and management in no-till field crops, with an emphasis on the mid-Atlantic region. Journal of Integrated Pest Management, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.1603/IPM11023

Douglas, M. R., & Tooker, J. F. (2016). Meta-analysis reveals that seed-applied neonicotinoids and pyrethroids have similar negative effects on abundance of arthropod natural enemies. PeerJ, 4, e2776. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.2776

Douglas, M. R., Rohr, J. R., & Tooker, J. F. (2015). Neonicotinoid insecticide travels through a soil food chain, disrupting biological control of non-target pests and decreasing soya bean yield. Journal of Applied Ecology, 52, 250–260. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12372

Dunn, M. D., Belur, P. D., & Malan, A. P. (2021). A review of the in vitro liquid mass culture of entomopathogenic nematodes. In Biocontrol Science and Technology (Vol. 31, Issue 1, pp. 1–21). Taylor and Francis Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1080/09583157.2020.1837072

El-Danasoury, H., & Iglesias-Piñeiro, J. (2017). Performance of the slug parasitic nematode Phasmarhabditis hermaphrodita under predicted conditions of winter warming. Journal of pesticide science, D16-097.

Faberi, A. J., López, A. N., Manetti, P. L., Clemente, N. L., & Castillo, H. A. Á. (2006). Growth and reproduction of the slug Deroceras laeve (Müller) (Pulmonata: Stylommatophora) under controlled conditions. In Spanish Journal of Agricultural Research (Vol. 4, Issue 4).

Felske, A., Rheims, H., Wokerink, A., Stackebrandt’, E., & Akkermans’, A. D. L. (1997). Ribosome analysis reveals prominent activity of an uncultured member of the class Actinobacteria in grassland soils. Microbiology, 143, 2983–2989.

Foltan, P., & Konvicka, M. (2008). A new method for marking slugs by ultraviolet-fluorescent dye. Journal of Molluscan Studies, 74(3), 293–297. https://doi.org/10.1093/mollus/eyn012

Fourie, H., Spaull, V. W., Jones, R. K., Daneel, M. S., & de Waele, D. (2017). Nematology in South Africa: A View from the 21st Century. In Nematology in South Africa: A View from the 21st Century. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-44210-5

Fox, L., & Landis, B. J. (1973). Notes on the predaceous habits of the gray field slug, Deroceras laeve. Environmental entomology, 2(2), 306-307.

Georgis, R., Koppenhöfer, A. M., Lacey, L. A., Bélair, G., Duncan, L. W., Grewal, P. S., Samish, M., Tan, L., Torr, P., & van Tol, R. W. H. M. (2006). Successes and failures in the use of parasitic nematodes for pest control. Biological Control, 38(1), 103–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2005.11.005

Gregory, W. W., & Musick, G. J. (1976). Insect management in reduced tillage systems. Bulletin of the ESA, 22(3), 302-304.

Hallett, K. C., Atfield, A., Comber, S., & Hutchinson, T. H. (2016). Developmental toxicity of metaldehyde in the embryos of Lymnaea stagnalis (Gastropoda: Pulmonata) co-exposed to the synergist piperonyl butoxide. Science of the Total Environment, 543, 37-43.

Hammond, R. B. (1985). Slugs as a new pest of soybeans. Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society, 364-366.

Horwitz, P., & Wilcox, B. A. (2005). Parasites, ecosystems and sustainability: An ecological and complex systems perspective. International Journal for Parasitology, 35(7), 725–732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.03.002

Howe, I. D., Dana, K., Ha, A. D., Colton, A., Tandingan, I., Ley, D., Rae, R. G., Ross, J., Wilson, M., Nermut, J., Zhao, Z., Mc, R. J., Id, D., & Denver, D. R. (2020). Phylogenetic evidence for the invasion of a commercialized European Phasmarhabditis hermaphrodita lineage into North America and New Zealand. Plos One , 15(8), e0237249. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237249

Kozłowski, J., & Jaskulska, M. (2014). The effect of grazing by the slug Arion vulgaris, Arion rufus and Deroceras reticulatum (Gastropoda: Pulmonata: Stylommatophora) on leguminous plants and other small-area crops. Journal of Plant Protection Research, 54(3), 258–266. https://doi.org/10.2478/jppr-2014-0039

Lacey, L. A., Grzywacz, D., Shapiro-Ilan, D. I., Frutos, R., Brownbridge, M., & Goettel, M. S. (2015). Insect pathogens as biological control agents: Back to the future. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 132, 1–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jip.2015.07.009

Laznik, Ž., Ross, J. L., Tóth, T., Lakatos, T., Vidrih, M., & Trdan, S. (2009). First record of the nematode Alloionema appendiculatum Schneider (Rhabditida: Alloionematidae) in Arionidae slugs in Slovenia. 17(2), 145. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

le Gall, M., & Tooker, J. F. (2017). Developing ecologically based pest management programs for terrestrial molluscs in field and forage crops. In Journal of Pest Science (Vol. 90, Issue 3, pp. 825–838). Springer Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-017-0858-8

Mc Donnell, R. J., Colton, A. J., Howe, D. K., & Denver, D. R. (2020). Lethality of four species of Phasmarhabditis (Nematoda: Rhabditidae) to the invasive slug, Deroceras reticulatum (Gastropoda: Agriolimacidae) in laboratory infectivity trials. Biological Control, 150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2020.104349

Mc Donnell, R. J., Paine, T. D., Stouthamer, R., Gormally, M. J., & Harwood, J. D. (2008). Molecular and Morphological Evidence for the Occurrence of Two New Species of Invasive Slugs in Kentucky, Arion intermedius Normand and Arion hortensis Férussac (Arionidae: Stylommatophora). Journal of the Kentucky Academy of Science, 69(2), 117–123. https://doi.org/10.3101/1098-7096-69.2.117

Mcmullen Ii, J. G., & Stock, S. P. (2014). In vivo and In vitro Rearing of Entomopathogenic Nematodes (Steinernematidae and Heterorhabditidae). https://doi.org/10.3791/52096

McMullen, J. G., Peterson, B. F., Forst, S., Blair, H. G., & Stock, S. P. (2017). Fitness costs of symbiont switching using entomopathogenic nematodes as a model. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-017-0939-6

Murrell, E. G. (2020). Challenges and Opportunities in Managing Pests in No-Till Farming Systems. In No-till Farming Systems for Sustainable Agriculture (pp. 127-140). Springer, Cham.

Nermuť, J., Holley, M., & Půža, V. (2020). Phasmarhabditis hermaphrodita is not the only slug killing nematode. Microbial and Nematode Control of Invertebrate Pests , 150, 152–156.

Nermuť, J., Holley, M., Ortmayer, L. F., & Půža, V. (2022). New players in the field: Ecology and biocontrol potential of three species of mollusc-parasitic nematodes of the genus Phasmarhabditis. BioControl. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10526-022-10160-8

Nermuť, J., Půža, V., & Mráček, Z. (2019). Bionomics of the slug-parasitic nematode Alloionema appendiculatum and its effect on the invasive pest slug Arion vulgaris. BioControl, 64(6), 697–707. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10526-019-09967-9

Nermuthacek˜, J., & Pudot over˜ ža, V. (2017). Slug parasitic nematodes: biology, parasitism, production and application. In CABI (Ed.), In Biocontrol agents: entomopathogenic and slug parasitic nematodes (pp. 533–547).

Orozco, R. A., Lee, M.-M., & Stock, P. S. (2014). Soil sampling and isolation of entomopathogenic nematodes . Journal of Visualized Experiments , 89, p.e52083.

Pearce, T. A. (2008). Land snails of limestone communities and update of land snail distributions in Pennsylvania. Final report for grant agreement WRCP-04016. Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Pittsburgh, PA.

Pérez-Campos, S.-J., Rodríguez-Hernández, A.-I., Del-Rocío López-Cuellar, M., Zepeda-Bastida, A., & Chavarría-Hernández, N. (2018). Biocontrol Science and Technology In-vitro liquid culture of the entomopathogenic nematode, Steinernema colombiense, in orbitally shaken flasks. https://doi.org/10.1080/09583157.2018.1499872

Pieterse, A., Malan, A. P., & Ross, J. L. (2017a). Nematodes that associate with terrestrial molluscs as definitive hosts, including Phasmarhabditis hermaphrodita (Rhabditida: Rhabditidae) and its development as a biological molluscicide. In Journal of Helminthology (Vol. 91, Issue 5, pp. 517–527). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X16000572

Pieterse, A., Malan, A. P., & Ross, J. L. (2017b). Nematodes that associate with terrestrial molluscs as definitive hosts, including Phasmarhabditis hermaphrodita (Rhabditida: Rhabditidae) and its development as a biological molluscicide. In Journal of Helminthology (Vol. 91, Issue 5, pp. 517–527). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X16000572

Pieterse, A., Malan, A. P., & Ross, J. L. (2020a). In vitro production and biocontrol potential of nematodes associated with molluscs [PhD, Stellenbosch University ]. https://scholar.sun.ac.za

Pieterse, A., Malan, A. P., & Ross, J. L. (2020b). Efficacy of a novel metaldehyde application method to control the brown garden snail, cornu aspersum (Helicidae), in south africa. Insects, 11(7), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects11070437

Pieterse, A., Rowson, B., Tiedt, L., Malan, A. P., Haukeland, S., & Ross, J. L. (2021). Phasmarhabditis kenyaensis n. Sp. (Nematoda: Rhabditidae) from the slug, Polytoxon robustum, in Kenya. Nematology, 23(2), 229–245. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685411-bja10040

Pieterse, A., Tiedt, L. R., Malan, A. P., & Ross, J. L. (2017b). First record of Phasmarhabditis papillosa (Nematoda: Rhabditidae) in South Africa, and its virulence against the invasive slug, Deroceras panormitanum. Nematology, 19(9), 1035–1050. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685411-00003105

Popp, J., Harangi-Rákos, M., Gabnai, Z., Balogh, P., Antal, G., & Bai, A. (2016). molecules Biofuels and Their Co-Products as Livestock Feed: Global Economic and Environmental Implications. Molecules , 21(3), 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules21030285

Popp, J., Pető, K., & Nagy, J. (2013). Pesticide productivity and food security. A review. In Agronomy for Sustainable Development (Vol. 33, Issue 1, pp. 243–255). Springer-Verlag France. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-012-0105-x

Půža, V., Mráček, Z., & Nermuť, J. (2016). Novelties in Pest Control by Entomopathogenic and Mollusc- Parasitic Nematodes. Integrated pest management (IPM): environmentally sound pest management (Intech, Ed.).

Rae, R. G., Robertson, J. F., & Wilson, M. J. (2009). Optimization of biological (Phasmarhabditis hermaphrodita) and chemical (iron phosphate and metaldehyde) slug control. Crop Protection, 28(9), 765–773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2009.04.005

Rae, R. G., Tourna, M., & Wilson, M. J. (2010). The slug parasitic nematode Phasmarhabditis hermaphrodita associates with complex and variable bacterial assemblages that do not affect its virulence. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 104(3), 222–226.

Rae, R., Verdun, C., Grewal, P. S., Robertson, J. F., & Wilson, M. J. (2007). Biological control of terrestrial molluscs using Phasmarhabditis hermaphrodita—progress and prospects. Pest Management Science: formerly Pesticide Science, 63(12), 1153-1164.

Rae, R., Verdun, C., Grewal, P. S., Robertson, J., & Wilson, M. J. (2007). Biological control of terrestrial molluscs using Phasmarhabditis hermaphrodita - Progress and prospects. In Pest Management Science (Vol. 63, Issue 12, pp. 1153–1164). https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.1424

Ross, J. L., Ivanova, E. S., Sirgel, W. F., Malan, A. P., & Wilson, M. J. (2012). Diversity and distribution of nematodes associated with terrestrial slugs in the Western Cape Province of South Africa. Journal of Helminthology, 86(2), 215–221. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X11000277

Rowen, E. K., Regan, K. H., Barbercheck, M. E., & Tooker, J. F. (2020). Is tillage beneficial or detrimental for insect and slug management? A meta-analysis. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 294, 106849.

Scheffer, M., Carpenter, S., & de Young, B. (2005). Cascading effects of overfishing marine systems. In Trends in Ecology and Evolution (Vol. 20, Issue 11, pp. 579–581). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2005.08.018

Schurkman, J., Dodge, C., Donnell, R. M., de Ley, I. T., & Dillman, A. R. (2022). Lethality of phasmarhabditis spp. (p. hermaphrodita, p. californica, and p. papillosa) nematodes to the grey field slug deroceras reticulatum on canna lilies in a lath house. Agronomy, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12010020

Sepasi, M., Damavandian, M. R., & Besheli, B. A. (2019). Mineral oil barrier is an effective alternative for suppression of damage by white snails Mineral oil barrier is an effective alternative for suppression of damage by white snails. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Section B-Soil & Plant Science , 69(2), 114–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/09064710.2018.1510026

Shapiro-Nan, D., & Hall, M. J. (2012). Susceptibility of adult nut curculio, Curculio hicoriae (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) to entomopathogenic nematodes under laboratory conditions. Journal of Entomological Science, 47(4), 375–378. https://doi.org/10.18474/0749-8004-47.4.375

Sharma, A., Sandhi, R. K., & Reddy, G. V. P. (2019). A review of interactions between insect biological control agents and semiochemicals. In Insects (Vol. 10, Issue 12). MDPI AG. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects10120439

Sicard, M., Ferdy, J. B., Pagès, S., le Brun, N., Godelle, B., Boemare, N., & Moulia, C. (2004). When mutualists are pathogens: An experimental study of the symbioses between Steinernema (entomopathogenic nematodes) and Xenorhabdus (bacteria). Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 17(5), 985–993. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1420-9101.2004.00748.x

Slotsbo, S., Fisker, K. v, Hansen, L. M., & Holmstrup, M. (2011). Drought tolerance in eggs and juveniles of the Iberian slug, Arion lusitanicus. Journal of Comparative Physiology B, 181, 1001–1009. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00360-011-0594-y

Tulli, M. C., Carmona, D. M., López, A. N., Manetti, P. L., Vincini, A. M., & Cendoya, G. (2009). Predación de la babosa Deroceras reticulatum (Pulmonata: Stylommathophora) por Scarites anthracinus (Coleoptera: Carabidae). Ecología austral, 19(1), 55-61.

Vernavá, M. N., Phillips-Aalten, P. M., Hughes, L. A., Rowcliffe, H., Wiltshire, C. W., & Glen, D. M. (2004). Influences of preceding cover crops on slug damage and biological control using Phasmarhabditis hermaphrodita. In Ann. appl. Biol (Vol. 145).

Wallace, J. M., Williams, A., Liebert, J. A., Ackroyd, V. J., Vann, R. A., Curran, W. S., Keene, C.L., VanGessel, M.J., Ryan, M.R., & Mirsky, S. B. (2017). Cover crop-based, organic rotational no-till corn and soybean production systems in the mid-Atlantic United States. Agriculture, 7(4), 34.

Willis, J. C., Bohan, D. A., Powers, S. J., Choi, Y. H., Park, J., & Gussin, E. (2008). The importance of temperature and moisture to the egg-laying behaviour of a pest slug, Deroceras reticulatum. Annals of Applied Biology , 153, 105–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7348.2008.00242.x

Wilson, M. J., Glen, D. M., & George, S. K. (1993). The rhabditid nematode Phasmarhabditis hermaphrodita as a potential biological control agent for slugs. Biocontrol Science and Technology, 3(4), 503-511.

Wilson, M. J., Glen, D. M., George, S. K., & Pearce, J. D. (1995). Selection of a bacterium for the mass production of Phasmarhabditis hermaphrodita (Nematoda : Rhabditidae) as a biocontrol agent for slugs. In Fundam. appl. NemalOl (Vol. 18, Issue 5).

Wilson, M. J., Glen, D. M., Pearee, J. D., & Rodgers, P. B. (1995). Monoxenic culture of the slug parasite Phasmarhabditis hermaphrodita (Nematoda: Rhabditidae) with different bacteria in liquid and solid phase Monoxenic culture of the slug parasite Phasmarhabditis hermaphrodita (Nematoda : Rhabditidae) with different bacteria in liquid and solid phase. In Fundam. appl. Nematol (Vol. 18, Issue 2). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/32972578

Wilson, M., & Rae, R. (2015). Phasmarhabditis hermaphrodita as a control agent for slugs. In Nematode Pathogenesis of Insects and Other Pests: Ecology and Applied Technologies for Sustainable Plant and Crop Protection (pp. 509–521). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-18266-7_21

Wilson, M., Glen, D. M., George, S. K., Pearce, J. D., & Wiltshire, C. W. (1994). Biological control of slugs in winter wheat using the rhabditid nematode Phasmarhabditis hermaphrodita. In Ann. appl. Biol (Vol. 125).