Final report for GNE22-295

Project Information

Blueberries are valued for their nutritional and health benefits due to high levels of anthocyanins and antioxidant compounds that support human health. To meet growing consumer demand for nutrient-rich produce while reducing phosphate runoff and fertilizer inputs, farmers are increasingly adopting sustainable practices such as inoculation with Ericoid Mycorrhizal Fungi (EMF), which form beneficial associations with blueberry roots. However, the long-term impact of EMF inoculation on fruit nutritional quality remains poorly understood, particularly across different blueberry genotypes.

To address this gap, I evaluated blueberry plants that were inoculated 11 years ago with EMF. I assessed anthocyanin content, antioxidant activity, berry mass and gene expression profiles in fruits from inoculated and uninoculated plants across three cultivars Duke, Spartan and Bluecrop. Biochemical assays measured fruit quality traits, while RNA sequencing revealed changes in gene activity associated with EMF treatment.

Eleven years post-inoculation, the results showed that EMF continues to influence fruit quality—but in a genotype-specific manner. Spartan showed increase in berry mass, but its antioxidant capacity was significantly reduced. Duke had a decrease in anthocyanin levels while Bluecrop had no significant effect of inoculation. Gene expression analysis confirmed persistent, genotype-dependent shifts in metabolic and stress-related pathways. These findings suggest that EMF inoculation can have lasting effects on fruit quality, but the outcomes vary significantly depending on the genetic background of the blueberry cultivar. This underscores the importance of selecting compatible genotypes when implementing EMF-based practices.

For farmers, this research provides valuable long-term insights. EMF inoculation is not universally beneficial, but when matched with responsive cultivars, it can enhance fruit quality and reduce reliance on chemical inputs. These results can empower growers to make informed decisions about cultivar selection and inoculation strategies, improving both sustainability and marketability.

The goal of this research was to evaluate whether inoculating blueberry roots with beneficial fungi specifically Ericoid Mycorrhizal Fungi (EMF), can influence berry anthocyanin content and antioxidant capacity, key compounds linked to health benefits, and impact gene expression. Understanding this relationship will help farmers make informed decisions about sustainable practices that not only enhance fruit quality but also support long-term plant health and productivity. Through controlled laboratory experiments, the research examined two main objectives:

Objective 1: Determine the anthocyanin content and antioxidant activity in blueberry fruits from both EMF-inoculated and uninoculated plants.

Objective 2: Identify gene expression patterns in blueberry fruits from inoculated and uninoculated plants.

The purpose of this project was to evaluate the effect of ericoid mycorrhizal fungi inoculation on fruit anthocyanin content, antioxidant activity and gene expression in Northern Highbush Blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum). The goal was to determine whether inoculating blueberry roots with beneficial fungi could influence berry anthocyanin levels, compounds known to promote human health.

In recent years, growing public awareness of health and wellness has led to significant shifts in dietary habits, with consumers increasingly seeking foods that offer enhanced nutritional benefits (Proestos, 2018). Blueberries have emerged as one of the most nutrient-dense fruits, largely due to their high antioxidant content, particularly anthocyanins, which contribute to immune support and overall well-being (Nicoletti et al., 2015; Wolfe, 2009). In response to evolving consumer preferences, farmers face the challenge of producing high-quality “superfoods” that meet both nutritional expectations and environmental standards. To achieve this, many growers have adopted sustainable agricultural practices, including the use of beneficial mycorrhizal fungi to reduce reliance on synthetic fertilizers and minimize phosphate runoff, this requires the purchase of commercial mycorrhizal fungi which manufacturers claim promotes plant growth but attributes of its effect on berry fruit quality is poorly understood.

Inoculation with mycorrhizal fungi has been shown to enhance the growth of highbush blueberry plants in the northeastern United States (Yang et al., 2002). Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi (AMF), a well-studied group of beneficial microbes, have demonstrated additional benefits including improved plant defense (Maffei et al., 2014), enhanced soil carbon sequestration (Wu et al., 2014), and increased nutrient uptake (Zhu et al., 2016). These advantages have made microbial inoculants a cornerstone of sustainable agriculture, promoting natural resource use without environmental degradation (Rashid et al., 2019). Positive effects of AMF inoculation have been documented in several crops such as citrus (Abobatta, 2019), tomato (Hart et al., 2015), and strawberry (Cecatto et al., 2016; Cordeiro et al., 2019; Lingua et al., 2013).

Despite the known benefits of ericoid mycorrhizal fungi in forming mutualistic associations with ericaceous plants like blueberries, their impact on fruit quality, particularly anthocyanin content and antioxidant properties remains poorly understood. While genotype-specific increases in fruit mass have been observed following EMF inoculation (Brody et al., 2019), farmers are primarily concerned with commercial value, which depends heavily on fruit quality rather than yield alone. Currently, there is limited guidance on whether inoculation influences these nutritional traits or if different inoculum types affect berry quality. To address this gap, the present study evaluated the long-term effects of EMF inoculation on anthocyanin content and gene expression in blueberries, offering growers practical insights to support both environmental sustainability and economic returns.

Research

Sampling design: The experimental plants were Northern Highbush Blueberry plants located at the Waterman Orchards in Johnson, VT. These plants were inoculated with ericoid mycorrhizal fungi 11 years ago. I sampled three cultivars, Duke, Spartan and Bluecrop that differed in their responses to inoculation. Previous studies by Brody et al. (2019) reported that inoculation with ericoid mycorrhizal fungi increased fruit mass in the Bluecrop cultivar, while Duke showed a reduction in fruit number. Spartan exhibited a decrease in the number of inflorescences, but floral traits in both Bluecrop and Duke remained unaffected by the inoculation. Bluecrop cultivar is the most widely planted in Vermont and provides fruits mid-July through mid-August. Duke cultivar is known to be cold hardy and can produce berries late spring to mid-summer while Spartan fruits are from June to August and can withstand cold winter. Random sampling was done in one row per cultivar per treatment (10 inoculated vs 10 uninoculated plants). The 3 cultivars chosen for sampling were all grown within the same block with each pair of rows (inoculated and uninoculated) 3 meters apart. The rationale was to maintain as similar an environment as possible so that the inoculation treatment is the main difference.

Sample collection: I harvested berries in year 1 (2022) and year 2 (2023). I collected 24 berries sampled from 4 branches per plant and have assayed the berries for each objective. Mature and immature berries were harvested separately from each plant. Anthocyanins are the major flavonoids in berries, and the choice of immature and mature fruits is because accumulation of anthocyanins begins at the onset of ripening. I randomly sampled 10 plants per treatment for each of the 3 cultivars, so a total of 120 plants were sampled from 2022 and 2023. Spartan cultivar was at the end of harvest when I sampled in 2022, so total mature berries were low and very few plants had immature berries. I had to work with only mature berries to maintain consistency in samples across cultivars. The sampled fruits were placed in labelled Ziploc bags, frozen with liquid nitrogen, and stored at -800C. For the first year of sample collection, I was assisted by Tom Michaels (a UVM Plant Biology major who has since graduated). For the second-year sample collection, I was assisted by Mia Randolph, a Plant Biology major at UVM who has since graduated.

Sandra Nnadi with Ben Waterman at the Waterman Orchards, Johnson VT

Mia Randolph at the Waterman Orchards, Johnson VT in 2023.

Objective 1: Determine the anthocyanin content and antioxidant activity in blueberry fruits.

To test this objective, I used two different methods. The first method directly measured berry anthocyanin content in berries from inoculated and uninoculated plants. The second method measured the antioxidant activity present in the berries from inoculated and uninoculated plants. Results were compared within and across genotypes.

Experiment 1.1 Determine blueberry anthocyanin content.

I successfully optimized the anthocyanin assay and extracted anthocyanin from the blueberry samples harvested in the first year. To prepare the samples for Anthocyanin extraction, I measured frozen berries (3 fruits per sample) and ground them into powder with liquid nitrogen in a ceramic mortar and pestle. I stored the ground tissue in a 50ml falcon tube at 80oC. To extract Anthocyanin from the blueberry samples, I measured ground tissue and added 2 µl of extraction buffer (1% HCL in methanol) per mg tissue to each sample, homogenized the samples using a vortex mixer and centrifuged at high speed for 5 mins. I transferred the supernatant into a new 15ml falcon tube and repeated the process until the pellet turned white. To determine the Anthocyanin content, I used the direct spectrophotometric method to measure the absorbance at 530 nm and 657 nm of the sample extracts.

I also validated the results obtained using a second method for anthocyanin measurement, the pH differential method. I eventually chose the pH differential method because it is more specific for anthocyanin determination. It takes advantage of the unique structural changes that anthocyanins undergo at different pH levels. The direct spectrophotometric method is less specific for determining anthocyanins because it measures the total absorbance of all compounds that absorb at the same wavelength as anthocyanins. This can include other phenolic compounds and pigments present in the sample, leading to potential interference and overestimation of anthocyanin content.

For the pH differential method, I prepared two buffers, pH 1.0 Potassium chloride and pH 4.5 Sodium acetate. I used two sets (A & B) of each sample extract and added each buffer to the sample set A and B respectively. I measured absorbance at 530nm and 700nm.

Experiment 1.2: Measure berry Antioxidant activity (DPPH Assay)

2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) is a violet-colored (free radical) reagent when dissolved in methanol. The presence of an antioxidant molecule reduces the DPPH free radical to give a pale-colored solution. The absorbance of the solution is measured (517nm) with a spectrophotometer and the value obtained is used to calculate the amount of antioxidant activity of the sample extracts.

I optimized the DPPH assay protocol to determine the antioxidant activity of the blueberry sample extracts. I prepared 0.1mM DPPH solution in 100ml of methanol. I added 1ml of 0.1mM DPPH solution to 1ml of sample extract, mixed it thoroughly and kept it in the dark for 30mins. Using a UV Spectrophotometer, I measured absorbance at 517nm. The DPPH solution without sample added was used as the control while 1% HCL in methanol was used as the blank.

Objective 2: Identify gene expression patterns in blueberry fruits from inoculated and uninoculated plants.

I conducted RNA sequencing experiments on blueberry fruits obtained from inoculated and uninoculated plants. I also analyzed the sequencing results with bioinformatics tools to identify gene expression patterns.

RNA Sequencing (RNA-seq) is a technique that utilizes next-generation sequencing to detect and quantify RNA molecules in a biological sample, providing a detailed view of gene expression within that sample. RNA-seq can tell us which genes are turned on in a cell, what their level of expression is, and at what times they are activated or shut off.

I ground 3 frozen fruits per sample using liquid nitrogen in a ceramic mortar and pestle. RNA was extracted from each sample (ground tissue ±0.80g) with the Macherey-Nagel Nucleospin RNA kit. Based on the previous observation from the Brody et al, (2019) paper, Bluecrop and Duke were selected for RNA sequencing. A total of 40 RNA samples (2 treatments per cultivar) were DNAse-treated with Invitrogen TURBO DNA-free kit and quantified using Invitrogen Qubit RNA high sensitivity assay kit. The RNA quality was verified with Bioanalyzer analysis at the Massively Parallel Sequencing Facility at the University of Vermont. RNA samples were stored in -800C and sent to Novogene Corporation Inc. (Sacramento, CA) for mRNA library preparation (PolyA enrichment) and sequencing using NovaSeq X plus series (PE 150). The 40 RNA samples were verified for quality and only 39 samples went through to the library preparation phase.

Sandra Nnadi in the laboratory grinding blueberry fruits with liquid nitrogen in a ceramic mortar and pestle.

Sample extracts obtained after Anthocyanin Extraction.

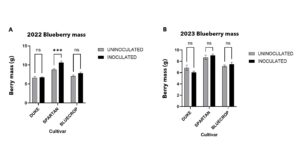

Effect of mycorrhizal inoculation on Berry Mass

Berry fruit mass plays a vital role in determining blueberry quality, as it significantly affects how appealing it is to consumers, how well the fruit sells, and how efficiently it can be harvested. Duke, Bluecrop, and Spartan are widely grown highbush blueberry varieties that typically produce medium to large-sized berries. Duke is an early-ripening cultivar that produces medium to large berries. Its firm fruit makes it well suited for efficient harvesting and post-harvest handling. Bluecrop, a widely grown mid-season variety, is known for its consistent fruit size and dependable performance across a range of growing environments. Spartan distinguishes itself with having larger berries and is favored for its sweet flavor and early harvest period. In the first year of sampling (2022), I observed that Spartan had larger berries and were significantly higher due to inoculation (Fig 1.) larger berries were also observed in 2023 but not significantly influenced by inoculation.

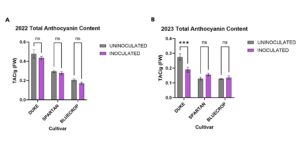

Genotype-specific effect of mycorrhizal inoculation on Anthocyanin content

Anthocyanins are a class of pigments responsible for the deep blue to purple color of blueberry fruits. These compounds are a major contributor to the high antioxidant capacity of blueberries, playing an important role in promoting health and enhancing their nutritional value. Anthocyanins also influence important fruit quality traits such as skin color, shelf life, and visual appeal, factors that directly impact consumer preference, growers and the marketplace. As such, the concentration and stability of anthocyanins are important considerations in cultivar selection, post-harvest handling, and breeding programs aimed at enhancing both the functional and commercial value of blueberry crops.

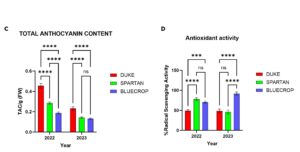

Mycorrhizal symbiosis is known to improve plant biomass in general and can influence blueberry floral traits in a genotype-specific way. I asked whether there is an effect of mycorrhizal fungi inoculation on blueberry anthocyanin content. I used two different methods to examine the anthocyanin content of inoculated and uninoculated blueberry fruits of three blueberry cultivars, Duke, Spartan and Bluecrop. I chose the method that is more specific in determining anthocyanin content (pH differential method). I found that berries from inoculated Duke plants from 2023 were significantly reduced in total anthocyanin content compared to uninoculated samples. For Bluecrop and Spartan cultivars, there was no significant difference in total anthocyanin content for both years (Fig 2).

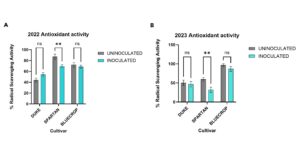

Effect of mycorrhizal inoculation on Antioxidant activity is genotype-specific

Antioxidants are natural substances that help protect plants and people from damage caused by stress, aging, and disease. Blueberries have one of the highest antioxidant capacities among fruits, due to compounds called anthocyanins, which also give the berries their deep blue color.

I observed genotype-specific effects of mycorrhizal inoculation on antioxidant activity. Spartan had a significant decrease in antioxidant activity in 2022 and 2023 (Fig 3). For Duke and Bluecrop, there was no significant effect of inoculation on antioxidant activity in both years.

Variation in berry traits among cultivars

Blueberry cultivars display considerable variation in berry traits that directly impact fruit quality, consumer appeal, and breeding potential. These differences include physical attributes such as berry size, shape, firmness, and skin color, as well as chemical composition including sweetness, acidity, phenolic content, and antioxidant activity. Developmental traits like flowering time, ripening period, and floral structure also vary, affecting pollination and harvest timing.

At the cultivar level, I observed significant differences in berry mass, total anthocyanin content, and antioxidant activity. Spartan had significantly larger berries than Duke and Bluecrop, this increase in berries was consistent for 2 years. Duke had smaller berries for both years (Fig 4a, 4b). Overall, Duke berries had significantly higher anthocyanin content than Spartan and Bluecrop (Fig 4c). Also at the cultivar level, Bluecrop and Spartan berries had significantly higher levels of antioxidant activity compared to Duke (Fig 4d).

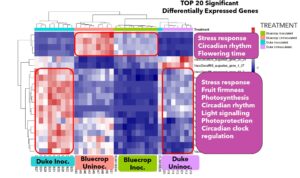

Gene expression levels influenced by mycorrhizal inoculation

Adding mycorrhizal fungi to crops can help plants turn on helpful genes that make them stronger and healthier. These fungi can boost the plant’s ability to handle stress like drought or salty soil, improve how roots take in nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus, and strengthen natural defenses against pests and diseases. As a result, plants can grow better and become more resilient in tough farming conditions.

Given that the blueberry plants received mycorrhizal fungi treatment 11 years ago, and genotype specific effects of inoculation were observed in some fruit traits. I investigated whether this inoculation had a lasting impact on their gene expression. I observed that genes involved in stress response, fruit firmness, circadian rhythm and photoprotection were active in Duke due to inoculation but in Bluecrop, these genes were suppressed (Fig 5).

The goal of this research was to evaluate whether inoculating blueberry roots with beneficial fungi specifically Ericoid Mycorrhizal Fungi (EMF), can influence berry anthocyanin content, antioxidant capacity, and impact gene expression. The objective was to determine the anthocyanin content, antioxidant activity and gene expression patterns in blueberry fruits from inoculated and uninoculated plants. I sampled three cultivars, Duke, Spartan and Bluecrop that were inoculated with ericoid mycorrhizal fungi 11 years ago and differed in their responses to inoculation. Through biochemical assays, molecular techniques, and bioinformatics, I completed all experimental work addressing both research objectives and conducted comprehensive data analysis.

The data revealed a clear and lasting impact of mycorrhizal inoculation on gene expression, indicating that even after 11 years, the plants may retain a form of long-term memory of the inoculation event. This enduring biological response highlights the potential for mycorrhizal fungi to influence plant development well beyond the initial treatment. Furthermore, the findings support evidence that mycorrhizal inoculation affects fruit traits in a genotype-specific manner, suggesting that different blueberry cultivars may respond uniquely to fungal associations. Though we looked at anthocyanin content and antioxidant activity, there are other genes that influence fruit quality. Further studies could explore other biochemical traits like fruit sweetness, firmness and possibly shelf life, to better understand the broader effects of long-term mycorrhizal associations on berry development and quality.

Education & outreach activities and participation summary

Participation summary:

It is important for results of funded applied research projects to reach farmers. Effective communication strategies can make reporting more understandable and create more sustainable farming opportunities. One of my goals for this project was to ensure that farmers, scientists, and the academic community were informed about the progress of the project and its outcomes.

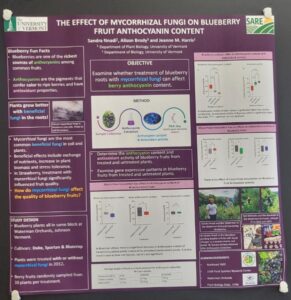

I presented a poster describing the ideas and methods for the project at the NOFA-VT winter conference 2023 which was held at UVM on Feb 18th, 2023. The Northeast Organic Farming Association of Vermont conference was an opportunity to meet with organic farmers and community partners who work towards a viable agricultural system. My poster, which highlighted my research ideas attracted a lot of participants and fostered good feedback and discussions. I also gave guest lectures at the Fungi Fest, held in September 2023, at Montpelier, Vermont and the New Moon Mycology Summit, held in August, 2023, at Greensboro, Vermont.

I presented the results of the anthocyanin and antioxidant analysis at the NOFA-VT winter conference held at the University of Vermont in February 2024. The poster presentation was a good follow up to the previous meeting in 2023 where I presented the ideas of the research. Participants were able to connect with the ideas and results; they asked questions about how to improve the use of mycorrhizal fungi at their farms and were eager to know how the practice influences fruit quality. The meeting gave me the opportunity to enhance my science communication skills with non-scientists and community members. I gave a talk at the Northern New England Microbiome Symposium in June 2024 and presented my research as a guest lecturer for a UVM Genetics class in April 2024. I also presented the progress of my research at the UVM Plant Biology Marvin seminar in December 2024 and October 2025.

Sandra Nnadi presenting a scientific poster to a participant at the NOFA-VT winter conference in February 2023 at the University of Vermont.

Poster highlighting research ideas presented at the NOFA-VT winter conference in February 2023.

Project Outcomes

My project, which investigates the effect of mycorrhizal fungi inoculation on blueberry anthocyanin content particularly its influence on fruit quality and gene expression has the potential to significantly enhance agricultural sustainability across economic, environmental, and social dimensions.

Environmental Sustainability

By demonstrating that a single mycorrhizal inoculation can have lasting effects on plant gene expression even after 11 years, the project supports the use of beneficial soil microbes as a low-input strategy for improving plant health and productivity. Mycorrhizal fungi enhance nutrient uptake (especially phosphorus and nitrogen), reduce the need for synthetic fertilizers, and improve soil structure and water retention. This reduces nutrient runoff and greenhouse gas emissions associated with fertilizer production and application. The long-term persistence of inoculation effects also means fewer applications are needed, minimizing soil disturbance and promoting microbial biodiversity.

Economic Benefits

While mycorrhizal inoculation was linked to a decrease in anthocyanin content and antioxidant activity, it led to an increase in berry size in the Spartan cultivar, which may still provide meaningful economic returns for growers. Even if these molecular changes don’t immediately translate into visible improvements in fruit quality, the gene expression data indicates that plants may be better equipped to handle stress, suggesting a long-term boost in resilience. For farmers managing fields with poor soil conditions or frequent environmental stress, mycorrhizal inoculation may represent a strategic, low-input investment in crop stability and productivity. If such inoculation results in even a 10–15% yield increase, it could generate significant revenue gains per hectare over time, especially in perennial crops like blueberries where benefits accumulate year after year. Continued research will be key to identifying cultivars that can retain high fruit quality while still reaping the resilience and yield advantages of mycorrhizal partnerships.

Social Benefits for Farmers

Mycorrhizal fungi can significantly improve nutrient acquisition, stress tolerance, and productivity in plants, especially under low-fertility or disturbed soil conditions. Their success, however, hinges on ecological compatibility between the soil environment, host plant, and fungal species (Fall et al., 2022, Qian et al., 2024, Rog et al., 2025, Scagel, 2005). Adopting mycorrhizal inoculation can promote more resilient farming systems, especially for small and medium-scale growers who may not have the resources for high-cost inputs. It empowers farmers to adopt more regenerative practices, by improving soil health and boosting long-term productivity. The genotype-specific effects observed in the study also create opportunities for farmers to be involved in selecting cultivars that perform best in their local conditions, making farming more personalized and effective. Furthermore, reducing chemical input contributes to safer working environments and promotes healthier communities around farms.

This project provides strong support for the use of microbial inoculants as part of sustainable agriculture, offering growers a practical, affordable, and eco-friendly way to boost crop performance and long-term farm viability. By showing how mycorrhizal fungi can influence plant resilience and fruit traits, it opens the door to broader adoption of biological inputs in farming systems. Future research can expand on these findings by exploring additional traits like fruit sweetness, firmness, and shelf life, and by testing inoculation effects across a wider range of cultivars and growing environments to refine best practices for different production settings.

Over the course of this project, both my advisor and I broadened our understanding of sustainable agriculture, particularly in relation to the long-term biological effects of microbial inoculants such as mycorrhizal fungi. While we initially focused on short-term outcomes like improved fruit quality, discovering gene expression changes that persisted more than a decade after inoculation expanded our perspective on plant memory and resilience. We began to see microbial inputs not merely as seasonal amendments, but as strategic, long-term investments in soil and crop health.

We also gained valuable skills in transcriptomic analysis, field sampling, and interpreting genotype-specific plant responses. These experiences helped us better connect molecular-level changes with practical agricultural outcomes. Our awareness of the complexity of plant–microbe interactions deepened, especially how these relationships influence fruit traits like anthocyanin content, antioxidant activity, and overall yield.

This project has deepened my commitment to exploring plant–microbe interactions and their potential in regenerative agriculture. I’m especially grateful to Ben Waterman who generously provided access to his experimental field (Waterman orchards), an opportunity that offered valuable insight into the practical needs of blueberry growers and how farm management practices can support both yield and fruit quality.

I’m particularly interested in exploring how microbial inoculants can be tailored to specific cultivars and growing conditions to optimize both yield and nutritional quality. My future work will likely focus on integrating microbiome analysis, transcriptomic and metabolomic tools with field-based studies to develop targeted microbial solutions for perennial crops such as berries, grapes, and fruit trees thereby bridging molecular insights with practical, sustainable farming applications.

One of the standout strengths of this project was its long-term scope. By studying blueberry plants 11 years after mycorrhizal inoculation, we uncovered enduring changes in gene expression that short-term studies would likely have missed. This reinforced the importance of longitudinal research in sustainable agriculture, particularly when evaluating biological inputs like microbial inoculants. It also emphasized the value of integrating molecular tools such as transcriptomics with field-based observations to generate meaningful insights into crop resilience and performance.

Despite the successes of the project, there were some limitations in the sampling approach. To prevent cross-contamination, berries were harvested on separate days for each cultivar. However, this method may have introduced variability due to changing weather or environmental conditions across those days, potentially affecting the accuracy of cultivar comparisons. A more robust strategy would have involved coordinating a larger team to collect all samples on the same day, minimizing external influences and ensuring more consistent data across cultivars.

Our focus on anthocyanin content and antioxidant activity provided useful data, but these traits alone don’t reflect the full range of fruit quality factors that matter to growers and consumers such as sweetness, firmness, shelf life, and disease resistance. A broader assessment of biochemical and physical traits would offer a more complete understanding of how mycorrhizal inoculation influences fruit development.

Another challenge was the variability in cultivar response. While the Spartan cultivar showed increased berry production, other cultivars reacted differently, making it difficult to draw universal conclusions. Also, Bluecrop exhibited reduced expression of genes linked to fruit firmness, flowering time and circadian rhythm following inoculation, suggesting possible trade-offs or context-specific interactions between EMF and their host plants. This highlights the need for future research to include a wider variety of cultivars and growing conditions to better capture the diversity of responses and refine inoculation strategies for specific genetic backgrounds and environments.

From an educational perspective, combining hands-on fieldwork with molecular lab techniques was a key strength of the project. This integration helped connect molecular concepts with real-world agricultural practices, deepening our understanding of how sustainable inputs like mycorrhizal fungi operate from cellular changes in gene expression to broader impacts on plant health and soil ecosystems. Moving forward, involving farmers directly through feedback and participatory research could make future studies more practical and impactful, ensuring that findings are aligned with on-the-ground needs and more likely to be adopted in diverse farming systems.

REFERENCES

Abobatta, W. F. (2019). Arbuscular mycorrhizal and citrus growth: Overview. Acta Scientific Microbiology, 2(6), 14–17.

Brody, A. K., Waterman, B., Ricketts, T. H., Degrassi, A. L., González, J. B., Harris, J. M., & Richardson, L. L. (2019). Genotype‐specific effects of ericoid mycorrhizae on floral traits and reproduction in Vaccinium corymbosum. American Journal of Botany, 106(11), 1412–1422. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajb2.1372

Cecatto, A. P., Ruiz, F. M., Calvete, E. O., Martínez, J., & Palencia, P. (2016). Mycorrhizal inoculation affects the phytochemical content in strawberry fruits. Acta Scientiarum. Agronomy, 38(2), 227. https://doi.org/10.4025/actasciagron.v38i2.27932

Cordeiro, E. C. N., Resende, J. T. V. D., Córdova, K. R. V., Nascimento, D. A., Saggin Júnior, O. J., Zeist, A. R., & Favaro, R. (2019). Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi action on the quality of strawberry fruits. Horticultura Brasileira, 37(4), 437–444. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0102-053620190412

Fall, A. F., Nakabonge, G., Ssekandi, J., Founoune-Mboup, H., Apori, S. O., Ndiaye, A., Badji, A., & Ngom, K. (2022). Roles of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on soil fertility: Contribution in the improvement of physical, chemical, and biological properties of the soil. Frontiers in Fungal Biology, 3, 723892. https://doi.org/10.3389/ffunb.2022.723892

Hart, M., Ehret, D. L., Krumbein, A., Leung, C., Murch, S., Turi, C., & Franken, P. (2015). Inoculation with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi improves the nutritional value of tomatoes. Mycorrhiza, 25(5), 359–376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00572-014-0617-0

Lingua, G., Bona, E., Manassero, P., Marsano, F., Todeschini, V., Cantamessa, S., Copetta, A., D’Agostino, G., Gamalero, E., & Berta, G. (2013). Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and plant growth-promoting pseudomonads increases anthocyanin concentration in strawberry fruits (Fragaria x ananassa var. Selva) in conditions of reduced fertilization. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 14(8), 16207–16225. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms140816207

Maffei, G., Miozzi, L., Fiorilli, V., Novero, M., Lanfranco, L., & Accotto, G. P. (2014). The arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis attenuates symptom severity and reduces virus concentration in tomato infected by Tomato yellow leaf curl Sardinia virus (Tylcsv). Mycorrhiza, 24(3), 179–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00572-013-0527-6

Nicoletti, A. M., Gularte, M. A., Elias, M. C., dos Santos, M. S., Ávila, B. P., Fernandes, J. L., & Peres, W. (2015). Blueberry bioactive properties and their benefits for health: A review. International Journal of New Technology and Research, 1(7), 51–57.

Proestos, C. (2018). Superfoods: Recent data on their role in the prevention of diseases. Current Research in Nutrition and Food Science Journal, 6(3), 576–593. https://doi.org/10.12944/CRNFSJ.6.3.02

Qian, S., Xu, Y., Zhang, Y., Wang, X., Niu, X., & Wang, P. (2024). Effect of amf inoculation on reducing excessive fertilizer use. Microorganisms, 12(8), 1550. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12081550

Rashid, M. H., Kamruzzaman, M., Haque, A. N. A., & Krehenbrink, M. (2019). Soil microbes for sustainable agriculture. In R. S. Meena, S. Kumar, J. S. Bohra, & M. L. Jat (Eds.), Sustainable Management of Soil and Environment (pp. 339–382). Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-8832-3_10

Rog, I., van der Heijden, M. G. A., Bender, F., Boussageon, R., Lambach, A., Schlaeppi, K., Bodenhausen, N., & Lutz, S. (2025). Mycorrhizal inoculation success depends on soil health and crop productivity. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 372, fnaf031. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsle/fnaf031

Scagel, C. F. (2005). Inoculation with ericoid mycorrhizal fungi alters fertilizer use of highbush blueberry cultivars. HortScience, 40(3), 786–794. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI.40.3.786

Wolfe, D. (2009). Superfoods: The food and medicine of the future. North Atlantic Books.

Wu, Q. S., Huang, Y. M., Li, Y., & He, X. H. (2014). Contribution of arbuscular mycorrhizas to glomalin-related soil protein, soil organic carbon and aggregate stability in citrus rhizosphere. International Journal of Agriculture and Biology, 16, 207–212.

Yang, W., Goulart, B. L., Demchak, K., & Li, Y. (2002). Interactive effects of mycorrhizal inoculation and organic soil amendments on nitrogen acquisition and growth of highbush blueberry. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science, 127

Zhu, X., Song, F., Liu, S., & Liu, F. (2016). Arbuscular mycorrhiza improve growth, nitrogen uptake, and nitrogen use efficiency in wheat grown under elevated CO₂. Mycorrhiza, 26