Progress report for GNE24-308

Project Information

Leveraging the soil microbial community to accelerate weed seed mortality in the soil could be a novel approach to ecologically manage weedy populations. With NE SARE funding, we examine whether natural crop-microbe-weed seed interactions can increase the soil microbes that accelerate weed seed mortality. Perennial forage crops have been shown to effectively reduce annual weed populations by disrupting weed life cycles, but one major knowledge gap remains: To what extent do diverse perennial crop mixtures affect weed seed mortality in the soil through microbial activity or abiotic conditions? Our treatments (7) include monocultures and all two- and three-species combinations of a perennial legume, forb and grass: alfalfa (Medicago sativa), forage chicory (Cichorium intybus), and orchard grass (Dactylis glomerata). We examine two weeds, Powell amaranth (a pigweed; Amaranthus powellii) and velvetleaf (Abutilon theophrasti), which are problematic on Pennsylvania farms. At the start of the experiment, we buried weed seeds within mesh bags in perennial treatments with retrieval of subsamples after 1, 1.5, 2 and 2.5 years of burial. Prior to receiving the grant, we measured soil abiotic conditions and conducted weed seed viability testing. With NE SARE funds, we conducted a thorough analysis of soil abiotic factors and A. powellii seed endophyte and soil microbial composition through Illumina 16S and ITS amplicon sequencing.

Perennial forage treatment did not affect A. powellii nor A. theophrasti seed mortality, nor did it affect the composition of bacteria or fungi associated with A. powellii seeds. However, increasing perennial forage richness increased seed mortality of A. theophrasti, but A. powellii exhibited greater seed mortality at lower levels of diversity. Interestingly, soil cations (Ca, Mg, and K) tended to be negatively associated with weed seed mortality. Our research suggests that perennial forage monocultures or mixtures do not vary in their ability to accelerate weed seed mortality in the soil, but we did uncover insights into microbial communities associated with weed seeds that could be promising for further research.

Results were shared through multilingual PSU Extension Events, a local grower conference, and a bilingual Amaranthus weed ID brochure. Currently, one paper "Influence of perennial forage communities on weed seed mortality and seed microbial associations" is in review at Weed Science and a second paper focused on the similarities between the weed seed and soil microbiome over time is in progress.

Objective 1: To what extent does the weed seed microbiome vary across time, and does the weed seed microbiome predict weed seed mortality?

Hypothesis 1: We hypothesize that seed microbiomes detected in our weed seed samples will predict seed mortality, and specifically, we hypothesize that samples with higher weed seed mortality will be colonized by more saprophytic and pathogenic microbes compared to seeds with higher mortality. Based on preliminary data, we have found greater microbial diversity in lower viability seeds compared to higher viability seeds, suggesting that the weed seed samples within our burial bags lose viability as they are colonized by the more diverse soil microbial community.

Objective 2: Is weed seed mortality and the weed seed microbiome predicted by the soil microbiota?

Hypothesis 2: We hypothesize that samples with higher weed seed mortality are colonized by more saprophytic and pathogenic microbes than seeds with lower mortality rates. These endophytic microbes will be reflected in the soil microbiota surrounding the weed seeds.

Application of Objectives 1 and 2:

With increased understanding of microbial taxa and/or communities that are associated with weed seed mortality in the soil, this will open the door for future research into management practices that increase these microbes to reduce the density of the weed seedbank. In the future, farmers may be able to test for the microbial weed-suppressive-potential of their soil or implement management practices to support those microbial populations, even possibly in the form of an inoculant.

Objective 3: Do soil abiotic factors predict weed seed mortality and the seed microbiome?

Hypothesis 3: We hypothesize that warmer soil conditions and higher N content will be associated with higher weed seed mortality due to increased microbial activity or induction of seed fatal germination.

Application of Objective 3:

If warmer temperatures are associated with weed seed mortality, horticultural producers could alter soil temperature at smaller scales through the use of black plastic mulch, high tunnels, or tarps. If soil nitrogen is associated with weed seed mortality, then targeted application of manure or synthetic nitrogen fertilizer would be an option for accelerating weed seed mortality in the soil.

The purpose of this project is to determine the effect of perennial crop diversity and associated biotic (microbial) and abiotic factors on weed seed mortality in the soil seedbank, which could lead to viable ecological weed management strategies.

Weed control is the greatest challenge for organic producers (Snyder et.al. 2022) and an obstacle for all farmers. Environmental and human health concerns have ignited support for agroecological weed management, especially as the Northeastern US is categorized at medium to high risk of pesticide pollution (McCauley et. al.2022; Sabio and Spers 2022; Tang et.al. 2021). Additionally, increasing herbicide-resistance (Heap 2024) causes conventional growers to seek alternative control methods (McCauley et. al.2022) as herbicide-resistant weeds cost US farmers about $10 billion/year due to losses (Palumbi 2001). Consequently, there is an incentive to examine agronomic factors which reduce existing weed seeds in soil seedbanks to decrease weed populations (Schwartz-Lazaro and Copes 2019).

Weed seeds in the soil are vulnerable to mortality, suggesting a potential method of weed control. Seeds have chemical defenses in their seed coats, and hard, thick seed coats (e.g. velvetleaf) enable seeds to persist in the soil for years (Davis et.al. 2016; Houlihan et.al. 2019). However, once the coat is cracked or penetrated, the seed is highly vulnerable to mortality. Pathogenic and saprophytic bacteria and fungi can result in ≤50% mortality of weed seeds in the soil but this varies across seed species, environmental conditions, and burial depth (Davis et.al. 2005; Chee-Sanford 2008; Wagner and Mitschunas 2008)

Thus far, few studies have examined the microbes that may cause seed mortality. Previous studies either examined general microbial communities but did not identify the specific microbial taxa (e.g. PCR DGGE; Davis et.al. 2006) or relied on culture-based methods (Chee-Sanford 2008) which are limiting as most microbes cannot be cultured. Therefore, we used Illumina Next-Generation Sequencing (16S and ITS amplicons) to examine the bacterial and fungal communities associated with weed seed mortality in a perennial forage diversity gradient.

Perennial crops grown for silage or hay can provide unique weed management benefits. The continual (and often dense) plant cover within perennial forages suppresses annual weed emergence and frequent mowing terminates weeds before set seed, thereby eliminating seed input into the seedbank (Meiss et.al. 2010; Nichols et.al. 2015). Increasing plant diversity in perennial forages can increase forage quality, and decrease disease and density regulation feedbacks compared to monocultures (Vukicevich et.al. 2016). However, it is not yet clear whether perennial forage species or plant functional groups can affect weed seed mortality through their effects on the soil microbiome or soil abiotic factors. Therefore, we examined how monocultures and mixtures of legume, grass and forb perennial forage crops affect weed seed mortality.

Additionally, we investigated whether perennial forage crop effects on weed seed mortality may be mediated through effects on the soil and seed microbiome and soil abiotic factors. Plants influence the soil microbiome, especially the rhizosphere, through N-fixing mutualisms, rhizodeposits, root architecture, and through litter inputs and decomposition (Drost et.al. 2020; Lowry et.al. 2024; Mafa‐Attoye et.al. 2023). Perennial crops may be especially strong at influencing the soil microbiome due to increased labile soil carbon and root exudates compared to annual cropping systems (Sprunger and Robertson 2018; Gallandt et.al. 1999). Organic matter inputs from functionally diverse perennial crops have varying effects on the C:N ratio, and a lower C:N ratio was associated with higher microbial predation of Abutilon theophrasti (Roumet et.al. 2016; Davis 2007). Additionally, the nitrate from legume tissue decomposition has been associated with increased Amaranthus powellii mortality, possibly due to fatal germination (Mohler et.al. 2018). While this ecological system could be driven by abiotic soil nutrients, research suggests that soil abiotic factors interact with soil microbes to influence microbial colonization in seeds, and ultimately seed mortality. Therefore, we examined if soil microbial diversity differs by perennial forage treatment and if differences in soil microbial diversity were associated with the weed seed microbiome and mortality.

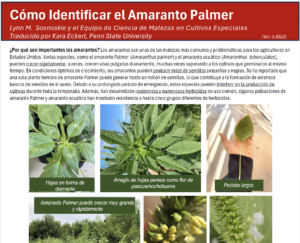

This research and anticipated outreach efforts will contribute to Northeast SARE's outcome statement by increasing farm sustainability, resilience, and economic viability through determining the microbial taxa responsible for weed seed mortality in the soil. Ultimately, this will enhance our ability to develop more ecological approaches to weed management by understanding how crop species and soil abiotic factors promote microbially-mediated weed seed mortality. Lastly, we translated an Amaranthus weed identification guide to Spanish, so that more farmers have access to this information.

Cooperators

- (Educator and Researcher)

- (Researcher)

Research

January 2026 Update

Since January 2025, we analyzed 16s and ITS microbiome data for the soil and A. powellii seed DNA using Dada2 for bioinformatic pipeline and conducted data analysis with Phyloseq, PCOA and PERMANOVA in adonis2. Kara's Master's Thesis was successfully defended based on these results! In the Fall of 2025, we began writing our first paper to be submitted to weed science mostly focused on the effect of perennial forages on weed seed mortality, soil abiotic effects on mortality and perennial forage effects on microbiomes. The paper was submitted in December 2025.

January 2025 Update

By the summer of 2024, we completed all field measurements, including soil abiotic factors and the final seed bag retrieval. In Fall 2024, we concluded seed viability testing from the Spring 2024 seed bag retrieval and we extracted DNA from the Spring 2024 seeds and soil samples. In November 2024, we submitted all 16s and ITS PCR products from seed and soil samples for amplicon sequencing on a Next Seq2000 at the Huck Institute's Genomics Core Facility at Penn State. Currently, we are analyzing microbiome sequencing data and processing soil N samples. We also have preliminary results for analyses of weed seed mortality, some soil abiotic factors (temperature and moisture) and biomass.

In 2021, the perennial forage diversity gradient was established by the Lowry Weed Ecology Lab. Through a small seed grant from the Weed Science Society of America (WSSA Innovation Grant), we obtained funding for microbial sequencing of the weed seed microbiome for only a single timepoint. Additional funds from NE SARE were used to analyze the seed and soil microbiomes and soil abiotic factors at additional timepoints over the study duration (2.5 years) which improved our understanding of how crop species and soil abiotic factors influence the soil microbial communities and colonization of weed seeds over time.

Experimental Design and Study Site

All objectives

The field site was established in September 2021 as a randomized complete block design with four blocks (4x7) at the Russell E. Larson Agricultural Research Center in Rock Springs, PA (40° 43′N, 77°56′W, 350m elevation). Soils are predominately comprised of Hagerstown silt loam (fine, mixed, mesic Typic Hapludalfs). Average air temperature at the site is 10.4°C with average winter temperatures of -1.4°C and average summer temperatures of 21.3°C; the site receives on average 1050.3mm of annual precipitation (NCEI 2024).

To evaluate the effect of perennial forage composition and diversity on microbial or abiotic mediated weed seed mortality in the soil seedbank, we examined 7 perennial treatments including monocultures and all possible mixtures of alfalfa (A)(Medicago sativa - legume), orchard grass (O)(Dactylis glomerata - grass), and forage chicory (C)(Cichorium intybus - forb) and are hereby represented as A, C, O, AC, AO, CO, ACO.

Each block consisted of 7 plots, each plot measuring 12.2 x 12.2m. See Appendix Figure 1.

Agronomic Management: Prior to planting, the field was chisel plowed, disked, and then a soil finisher and cultimulcher were used to prepare the seedbed. Alfalfa, chicory, and orchard grass were drill seeded on 19-cm rows (see Appendix Table 1). Due to high winter kill, the chicory was re-seeded in April 2022. We applied an equal low-level amount of N fertilizer across all treatments, despite chicory and orchardgrass not being legumes, to ensure any effects on seed mortality were due solely to the perennial forage treatments. In Spring 2022 we applied 30 kg Nha-1 equally across the entire field, and in Spring 2023 we increased the N amount we applied to 56 kg ha-1. Prior to planting and again in Spring 2023, we added P and K according to soil test recommendations. We applied Lambda cyhalothrin (Warrior II, Syngenta Crop Protection,Greensboro, NC) once in July 2022 at 0.034 kg ai ha-1 for control of leaf hoppers (Empoasca fabae).No herbicides were used throughout the study duration.The field was mowed four times per year when the alfalfa was at bud to early flowering stage, dried and baled for hay.

Abiotic Monitoring

Objective 3

We recorded soil moisture (VWC) weekly during the 2023 growing season (early May – late Oct) using a HydroSense II soil probe; only three measurement time points were taken in 2024 because the last seed extraction time point was in May 2024. Soil temperature readings were collected via HOBO sensors (1 per plot) which collect data every hour and were buried 5cm (2in) below the soil surface, which corresponds with the depth of the seed bags. The HOBO sensors were buried in plots in 2023 and removed in May 2024. During the winter between 2023 and 2024, five HOBO sensors malfunctioned, and therefore temperature data for these plots were removed from the dataset. We then calculated the daily average, maximum, and minimum temperature for each plot across the duration in which the HOBO sensors were deployed in the field.

Soil samples were collected twice per year in Spring 2023, Fall 2023, and Spring 2024 for inorganic nitrogen(N) analysis, but because other nutrients are less dynamic than N, we sampled soil once per year (Spring 2023 and 2024) for a full spectrum Mehlich 3 (ICP) analysis. For soil sampling we used a 2.5 cm diameter corer and collected 6 soil samples per plot at a depth of 20cm. Soil samples were then homogenized and a portion sent to the Penn State Ag Analytical Services Lab for the Mehlich 3 analysis. To quantify soil inorganic N concentration, we incubated 20 g of fresh soil with 100 ml 2M KCl for 1 h on a shaker, then filtered extracts were frozen at-20°C until both NH4-N and NO3-N could be quantified based on the Berthelot and Greiss reaction, respectively.

Biomass Collection

All objectives

Forage biomass was collected 4x per year (immediately prior to the field being mowed for harvest) within a 0.25m2 quadrat (2 samples per plot), when alfalfa was at bud stage. Biomass was cut using electric hand sheers 5cm (2in) above the soil surface, sorted to species, dried at 60°C and weighed.

Weed Seed Mortality Assessment, Soil Microbial Sampling, and Processing

All objectives

Weed seeds of Powell amaranth (a pigweed; Amaranthus powellii) and velvetleaf (Abutilon theophrasti) were collected in October 2021. A. powellii is a problematic and increasingly herbicide-resistant species (Aicklen et.al. 2022) and A. theophrasti is a persistent species in the weed seedbank due to its hard seed coat (Davis et.al. 2016). We used an air column to remove chaff and poor-quality seed and then treated A. theophrasti seed with chloroform for 24hrs to control for velvetleaf seed beetle (Althaeus folkertsi). Seeds of each species(100 A. theophrasti and 150 A. powellii, only one species per bag) were combined with 10g of sieved soil (2mm sieve) into fine mesh organza bags. The initial mortality of A. theophrasti was approximately 30%, while starting mortality for A.powellii was approximately 3%. Bags were then sewn shut and a hex nut was attached so bags could be located with a metal detector. In October 2021, we buried weed seed bags (10 bags of each species per plot) at a 5 cm depth adjacent to the crop row.

We first retrieved weed seed bags from the field at year 1 (Fall 2022) and then subsequently at 6-month intervals (Spring 2023, Fall 2023, and Spring 2024). At each timepoint, we retrieved 2 seed bags of each species per plot and immediately placed them on ice to limit disruption of the weed seed microbiome. The seeds were processed within 24 hours. Additionally, soil samples were collected from soil immediately surrounding the seed bags (to examine the soil impact on possible seed microbial shifts) and frozen for microbial analysis (Fall 2023 & Spring 2024 only).

After retrieval, we pooled the two bags of each species collected from each plot,washed the contents of the seed and soil mixture in EtOH-sanitized sieves to remove soil (500μM sieves). We counted all intact seeds per bag to obtain the proportion of the original seeds we recovered at each retrieval timepoint (% Recovery)

Equation 1:

% Recovery = (# of seeds recovered) / (# of seeds originally placed in bag)

We randomly selected 100 A. powellii and 11 A. theophrasti seeds (equivalent to ~ 100mg) and immediately placed them on ice for microbial processing. Within 24 hours of washing the seed bags, we surface sterilized (10% bleach for 10 min with 3 rinses in sterile water)(Ercoli et.al. 2007; Chakrabarti 1977) and freeze dried the seeds designated for microbial analysis. Seeds were freeze-dried in sterilized microcentrifuge tube covered with breathable sealing film in a freeze dryer for 10 hours at-26°C and <500m Torr. With SARE funding, only the A. powellii seeds were used for future microbial processing. The remaining seeds were stored at 4°C for viability/mortality testing. See Appendix Figure 2.

To evaluate weed seed mortality, we conducted tetrazolium (TZ) testing according to the AOSA handbook (Miller 2010) using 0.1% TZ with minor alterations; A. powellii seeds were pierced instead of bisected for TZ staining and then later dissected and A. theophrasti seeds were nicked (scarified) to quicken imbibition. Initial mortality testing protocols for A. powellii seeds in Fall 2022 (the first retrieval) varied from the above method and were not as reliable as the later developed method; therefore, A. powellii mortality data from this timepoint were discarded. To account for the microbial subsample of unknown mortality, total percent weed seed mortality (Mtotal ) was calculated as:

Equation 2:

Mtotal= 1 - ((% Recovery) x (% TZ viable))

Seed mortality data analysis:

To determine whether perennial forage community influences weed seed mortality, we used generalized linear mixed effects models with a beta distribution (recommended for proportional data) with forage treatment as a fixed effect and block as a random effect. All data analyses will occur in R (version 2023.09.1).

Microbial DNA Extraction and Sequencing

All objectives

We used the Qiagen DNeasy Plant Mini Kit to extract DNA of seed endophytic microbes. The Qiagen kit's 20mg restriction of biological tissue greatly limits the number of seeds we could extract from (ex. For velvetleaf, 3 seeds may reach 20mg). To obtain a more representative sample, we pooled subsamples to reach an initial 40mg (2x) weed seeds, ground in a bead mill, and doubled the extraction solutions for the initial steps. Then only 1x of lysate (350uL) was put into the Qiagen Shredder Column and normal protocols were followed thereafter. Additionally, we extracted DNA from the original, unburied seeds collected in Fall 2021 (used to fill the seed bags) to determine a baseline of microbial endophytes. We extracted DNA from soil, frozen from field collection, using the Qiagen Power Soil Kit. Negative controls to account for contaminants in the processing steps included (1) blank runs on each extraction kit as well as (2) extractions of sterilized metal beads that were subjected to the same protocols as the seeds (surface sterilization, freeze drying, weighing, etc.) and would indicate contaminants in processing steps. Extracted DNA was quantified using a Qubit Fluorometer (broad spectrum kit) and all the negative controls had undetectable amounts of DNA.

Then, we performed the first of a two-step amplicon PCR process using universal primers with Illumina adapters to amplify the ITS (1-2) marker region for fungal taxonomic diversity and the 16S rRNA gene (V4) region for bacterial taxonomic diversity. For the initial PCR reaction, we used ITS 1-2 primers (Gardes and Bruns 1993; Illumina 2019) or 16S rRNA gene V4 515F and 806R (Parada et al. 2016; Apprill et al. 2015), with Illumina adapters. For both ITS and 16S rRNA gene amplification, we used InvitrogenTM 2X PlatinumTM SuperfiTM II Green PCR Master Mix to run 20 μL PCR reactions containing: 10 μL mastermix (1x), 0.5 μM each forward and reverse primer, ~15 ng DNA, and sterile nuclease free water to reach 20 μL (concentrations are listed as final concentrations). pPNA and mPNA blockers from PNABio were added to 16S rRNA gene reactions for a final concentration of 1.25 μM each to reduce amplification of plastids and mitochondria, respectively. PCRs were conducted the same for both 16S rRNA and ITS and run on a thermocycler according to the Superfi II Mastermix protocol: initial denaturing (98°C for 30sec), denature-anneal-extend repeating 30 times (98°C for 10 sec, 60°C for 10 sec, 72°C for 15 sec), final extension (72°C for five min) and a hold at 4°C (Invitrogen 2022). PCR blanks (PCR reagents without DNA) were also run to identify any contamination in the PCR reagents. PCR products were checked using a 2% agarose gel, and all controls had no visible amplification. Samples were then submitted to the Penn State University Huck Institute’s Genomics Core Facility where a second round of PCR was completed to attach index barcodes for sample identification and Illumina sequence adapters, and then amplicons were sequenced (175k pair-end reads) with the Illumina NextSeq 2000 XLEAP P1 600 cycle kit and performing 300 x 300 paired-end sequencing.

Microbiome Data Processing and Analysis

The sequences were demultiplexed by the sequencing facility. We used the DADA2 pipeline (version 3.18; Callahan et al. 2016) to filter, remove primers, trim reads (according to phred score), pseudo-pool samples during sample inference, pair reads and create ASV (Amplicon Sequence Variant) abundance tables. For 16S rRNA gene data, after construction of the sequence table in dada2, only paired ASV’s with length of 254 bp (the length of the v4 segment) were selected for downstream processing; selecting ASV’s of the expected length (based on primers) is intended to remove noise from longer segments likely created from non-specific priming (Callahan et al. 2016). The majority of the ASV’s were exactly 254 bp. We used the GreenGenes2 database (version 2024.09 genus level) (Callahan et al. 2016; McDonald et al. 2024) for 16S rRNA gene taxonomic assignment and the UNITE All-Eukaryotes database (Abarenkov et al. 2024) for ITS taxonomic assignment. Then in “phyloseq” (version 1.46), we removed all 16S rRNA gene ASVs not classified as bacteria, ASVs unclassified at the phylum level as well as 16S rRNA gene ASV's associated with mitochondria or chloroplasts. For ITS, we removed all non-fungal ASVs and all ASVs unclassified at the phylum level. Additionally, we removed poor quality ITS ASVs containing 20 base pairs repetitions or longer homopolymers, which are common to ITS (Lindahl et al. 2013). To eliminate the influence of rare ASVs in both 16S rRNA gene and ITS, we removed all ASVs that consisted of less than 20 total reads or were found in less than 5% of samples. Both the 16S rRNA gene and ITS samples were independently rarefied to the minimum number of reads per sample using “phyloseq” (function rarefy_even_depth), which was 8,284 reads for 16S rRNA gene and 38,980 reads for ITS. We did this because rarefying helps obtain reliable and comparable estimates of alpha diversity across variation in sequencing depth (Weiss et al. 2017). All downstream analyses occurred on rarefied datasets.

To examine whether the perennial forage treatment affected the A.powellii seed microbiome,we analyzed 16S rRNA gene and ITS data separately and performed a PERMANOVA on the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrix using the adonis2 function in the vegan package in R (Oksanen et al.2025), and pairwise comparisons between treatments were performed with the pairwise.adonis function in the pairwiseAdonis package. To visualize A.powellii seed communities, we performed Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) on both the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrix and a Jaccard dissimilarity matrix (after converting the community matrix to presence-absence). Finally, we calculated the Observed and Shannon Diversity using the estimate_richness function in Phyloseq, and we examined whether both forage richness and treatment affected both diversity metrics for both weed species using linear mixed effect models with richness or treatment,retrieval timepoint, and their interaction as fixed effects and block as the random effect.

Preliminary Results

Table 1. Perennial forage treatment abbreviations. The acronyms will be used throughout the results and discussion.

| Treatment | Abbreviation |

| Alfalfa (Medicago sativa) | A |

| Chicory (Cichorium intybus) | C |

| Orchard Grass (Dactylis glomerata) | O |

| Alfalfa – Chicory | AC |

| Alfalfa – Orchard Grass | AO |

| Chicory – Orchard Grass | CO |

| Alfalfa – Chicory – Orchard Grass | ACO |

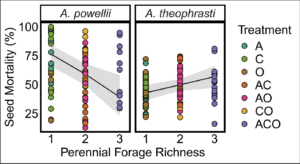

We found partial, yet inconsistent support for our hypothesis that increasing perennial forage richness increased seed mortality. Across all seed retrieval timepoints, increasing perennial forage richness increased seed mortality of A. theophrasti (slope=0.28, p=0.042; Figure 1); however, for A. powellii, we found the opposite trend of greater seed mortality at lower of diversity (slope=-0.8, p= 0.003 ).

Figure 1. Effect of perennial forage richness (1, 2, or 3 species) on seed mortality of A. powellii and A. theophrasti. Treatments include alfalfa (A), chicory (C), orchardgrass (O), and all combinations of the two and three-species mixtures.

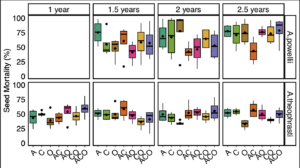

We found no consistent effect of perennial forage treatment on weed seed mortality (Figure 2). For both species, the effect of perennial forage treatment (or lack thereof) did not vary across seed retrieval time points (treatment:time point p >0.1). When analyzing across all seed extraction timepoints, we found a significant effect of perennial forage treatment on A. powellii seed mortality (treatment:X2 =14.8, p = 0.022), but when we controlled for multiple comparisons, we found no significant differences between treatments. This is likely due to the high variability in treatment effects on seed mortality both within and between timepoints. Perennial forage treatment did not affect A. theophrasti mortality across any of the seed retrieval timepoints (X2 = 10.5, p =3490.105)

Figure 2. Effect of perennial forage treatments on seed mortality of A. powellii and A. theophrasti across the four seed retrieval timepoints, including 1, 1.5, 2, and 2.5 years buried in the soil within the perennial forage treatments. Treatments include alfalfa (A), chicory (C), orchardgrass (O), and all combinations of the two- and three-species mixtures.

We had expected that soil abiotic conditions would explain the effect of our perennial forage treatments on weed seed mortality. Despite not finding any consistent effects of our perennial forage communities on seed mortality, variation in some, but not all, soil abiotic conditions predicted weed seed mortality. Unexpectedly, soil cations were the strongest soil conditions predictors of seed mortality. Calcium (Ca) and potassium (K) concentration were negatively associated with A. theophrasti seed mortality (Table 2, p=0.032 and p=0.003, respectively), while magnesium (Mg) was negatively associated with A. powellii seed mortality (p=0.001). Interestingly, we found the lowest level of K, Ca, and Mg in the alfalfa monoculture (data not shown), which also consistently had relatively high levels of mortality (Figure 3). Alfalfa is known to heavily utilize and deplete soil K (Kelling 2000), and since the alfalfa monoculture and mixtures were higher yielding, K cations were likely removed from the soil at a higher rate (Arnall, 2024). Similarly, A. theophrasti mortality tended to be low in the orchardgrass monoculture (Figure 3), which had relatively high levels of soil K and Mg (data not shown).

Table 2. Results from generalized linear mixed effect models testing whether soil abiotic conditions predict mortality of A. theophrasti and A. powellii seeds. Soil abiotic conditions and mortality for each plot were averaged across timepoints.

|

Soil Abiotic Factor |

Range |

Weed Species |

Slope |

P value |

|

Average Temperature |

10.7-12.6 °C |

A. theophrasti |

-0.48 |

0.038 |

|

A. powellii |

-0.16 |

0.598 |

||

|

Moisture |

21.6-24.8% |

A. theophrasti |

0.00 |

0.980 |

|

A. powellii |

0.13 |

0.577 |

||

|

pH |

6.7-7.3 |

A. theophrasti |

-0.52 |

0.138 |

|

A. powellii |

-1.42 |

0.059 |

||

|

Inorganic N |

5.9 -13.7 |

A. theophrasti |

0.06 |

0.232 |

|

A. powellii |

0.09 |

0.411 |

||

|

P |

16.5-50 ppm |

A. theophrasti |

-0.01 |

0.502 |

|

A. powellii |

0.04 |

0.097 |

||

|

K |

49-151 ppm |

A. theophrasti |

-0.01 |

0.003 |

|

A. powellii |

-0.00 |

0.857 |

||

|

Ca* |

1194- 1758 ppm |

A. theophrasti |

-1.09 |

0.032 |

|

A. powellii |

-3.28 |

<0.001 |

||

|

Mg |

116-291 ppm |

A. theophrasti |

0.00 |

0.126 |

|

A. powellii |

-0.01 |

<0.001 |

||

|

S |

5.25 – 8.5 ppm |

A. theophrasti |

0.01 |

0.918 |

|

A. powellii |

0.15 |

0.517 |

||

|

*Ca was log-transformed to meet assumptions of normality, therefore slope estimates are on the logarithmic scale. |

||||

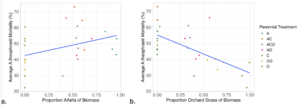

Interestingly, we found that in Spring 2024 (2.5 years buried), A. theophrasti seed mortality was positively associated with the proportion of the biomass that was alfalfa (legume – N fixer) and negatively associated with the proportion of the biomass that was orchard grass (a N scavenger) (Figure 3). Originally we hypothesized that legumes, with alterations in soil N and N cycling bacteria, may have played a role in weed seed mortality but in our study, soil N did not affect weed seed mortality. However, we did not observe much variation in soil N which limits our understanding of soil N and weed seed mortality. Therefore, the association between proportion alfalfa and proportion orchardgrass and mortality is more likely tied to the different Ca and K levels in the soil between alfalfa and orchardgrass treatments.

Figure 3. Biomass composition has a significant effect on A. theophrasti mortality in Spring 2024; there is positive association with proportion of alfalfa (a; p=0.038, RMSE = 0.11) and a negative association with proportion of orchard grass (b; p= 1.58e-05, RMSE= 0.09). See Table 1 for treatment abbreviations.

Perennial forage treatments had no effect on A. powellii seed microbiomes

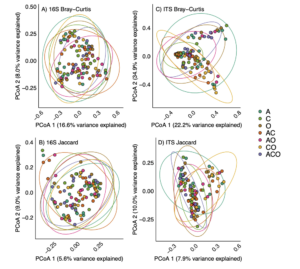

We found no support for our hypothesis that perennial forage community would affect the microbiome within A. powellii seeds, as neither bacterial (F=1.16, p = 0.06) nor fungal (F=1.38, p =0.07) communities varied across the perennial forage monocultures, bicultures, or the three-way mixture (Figure 4). Despite finding a marginal effect of treatment on both bacterial and fungal communities (p-values between 0.05 and 0.1), we found no evidence that any two treatments differed from one another when we conducted pairwise comparisons.

Figure 4. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) on Bray-Curtis (A and C) or Jaccard (B and D) dissimilarities of bacterial (A and B) and fungal (C and D) community composition in A. powellii seeds buried in perennial forage monocultures and mixtures. Treatments include alfalfa (A), chicory (C), orchardgrass (O), and all combinations of the two and three-species mixtures.

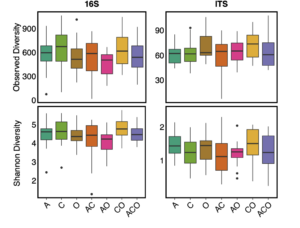

We also found no support for our hypothesis that increased perennial forage diversity (i.e. richness) would increase microbial diversity within A. powellii seeds (Figure 5, p-values>0.01). Instead, we found that perennial forage richness had no effect on Shannon or Observed diversity of bacterial or fungal microbial communities within A. powellii seeds. Interestingly, we did find a significant effect of perennial forage treatment on bacterial Shannon diversity (F=2.58, p=0.024), but when we controlled for pairwise comparisons, we found no two treatments differed from each other. However, A.powellii seeds collected within the perennial forage treatments did not differ in either bacterial Observed or fungal Shannon or Observed diversity (data not shown).

Figure 5. Observed and Shannon diversity of bacterial (16S) and fungal communities (ITS) in A. powellii seeds buried in perennial forage monocultures and mixtures. Treatments include alfalfa (A), chicory (C), orchardgrass (O), and all combinations of the two and three-species mixtures.

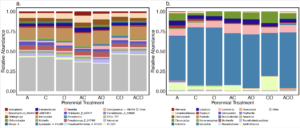

As previously reported in other studies, many bacterial genera found in A. powellii seeds were in the Pseudomonadota, Actinomycetota, or Bacteroidota phylum (Figure 6; Acuña et al. 2025; Johnston-Monje et al. 2021). The most abundant Actinomycetota included the genera Kineosporia, Actinoplanes, and Kribbellam. The Bacteroidota phylum included Chitinophaga, whose species may break down chitin in cell walls (Kobayashi & Crouch 2009; Fernandes et al. 2021), and Flavobacterium, which has been found to have both pathogenic and plant growth-promoting functions (Seo et al. 2024). Finally, Pseudomonadota also included genera that could be both pathogenic and plant growth promoters. For example, the known plant pathogen Pseudomonas fluorescens D7 is a soil-borne pathogen and has previously been tested as a biocontrol agent for the invasive plant Bromus tectorum (Dooley and Beckstead, 2010; Kennedy et al. 1991). In contrast, Bradyrhizobium is a genera of known plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) often associated with the rhizosphere, but which can also be a seed endophyte, especially in legumes (Mataranyika et al. 2024). Variovorax has also been reported to improve plant health, including increasing wheat germination under stress (Acuña et al. 2024). Other Pseudomonadota genera are often characterized as saprotrophs, including Lysobacter, a genus containing species that release lytic enzymes to compete for space with other microbes (Fernandes et al. 2021; Lin et al. 2023), but can also protect against pathogens (Kobayashi & Crouch 2009).

The most abundant phyla of fungi within A. powellii seeds were Ascomycota and Basidiomycota (Figure 6). Overwhelmingly, the most abundant genus was Melanodiplodia, which, along with the next most abundant genus, Lachnellula (both Ascomycota), are saprotrophs that degrade wood and other recalcitrant materials (Põlme et al. 2020). Multiple Ascomycota pathogenic fungi were also found in A. powellii seeds, including Fusarium, Alternaria, Ilyonectria, and Cladosporium, genera which have been associated with weed seed colonization and seed decay (Pitty et al. 1987; Põlme et al. 2020; Androsiuk et al. 2022). The most abundant Basidiomycota were not yet classified into genera, but came from the Ceratobasidiaceae family, which includes both plant pathogens and saprotrophs, and has been previously found in orchid seeds during germination (Zhao et al. 2024).

Figure 6. Relative abundance of the top 20 most abundant genera of (a) bacterial and (b) fungal within A.powellii seed buried in the perennial forage treatments, which include alfalfa (A), chicory (C), orchardgrass (O), and all combinations of the two and three species mixtures.

Weed Seed Microbiome is Associated with Weed Seed Mortality

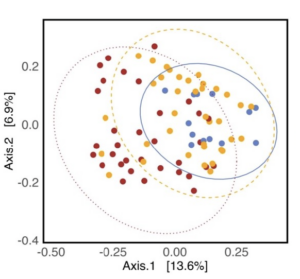

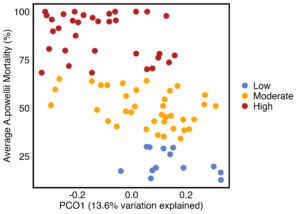

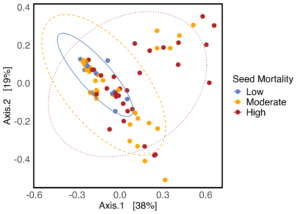

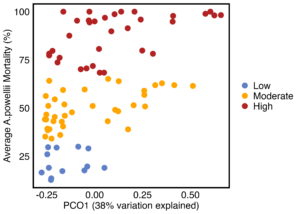

As hypothesized, the A. powellii weed seed microbiome varied across weed seed mortality. Across all seasons, the most predictive dimension from the bacterial 16S PCoA (PCo1 that explains 13.6% of bacterial community variation), was associated with A. powellii seed mortality (Figure 7b: p < 0.001). A similar association was seen with fungal PCO1 and weed seed mortality (Figure 8b: p<0.001). Additionally, both the A. powellii seed bacterial and fungal communities varied across mortality category, with differences between the low and high levels of mortality, as well as moderate and high levels of mortality (bacterial Figure 7a, F=3.12, p=0.001; fungal Figure 8a, F=3.6, p=0.001). We see that seed samples with low mortality grouped more tightly, indicating that these microbial communities were more similar, but as mortality increases to moderate and high levels, the microbial communities became more dissimilar and spread apart within the ordination space. This possibly suggests colonization by diverse soil microbes as seed mortality increases.

Figure 7. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) ordination calculated on Bray Curtis distances shows A. powellii seed bacterial communities vary across weed seed mortality category (7a; PERMANOVA F=3.12, p = 0.001). The first dimension of the PCoA (that explains 13.6% of bacterial community variation) is associated with A. powellii seed mortality (7b; p < 0.001). Mortality categories represent 33.3% intervals with low mortality starting at 0% and high mortality reaching 100%.

Figure 8. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) ordination calculated on Bray Curtis distances shows differences in A. powellii seed fungal communities based on weed seed mortality category (Figure 8a: PERMANOVA F=3.6, p = 0.001). The first dimension of the PCoA (that explains 38% of fungal community variation) is associated with A. powellii seed mortality (8b; p < 0.001). Mortality categories represent 33.3% intervals with low mortality starting at 0% and high mortality reaching 100%.

Preliminary Discussion

There are multiple factors that could have limited our ability to detect any effect of our perennial forage treatments on weed seed mortality. First, within a plot, the forage crop stand could be quite uneven, and this allowed for increased weed encroachment that likely altered potential effects of our treatments. Especially after 2 years of forage establishment, grass weed (many Poa sp.) encroachment was significant in alfalfa plots (especially alfalfa monocultures), and white clover (Trifolium repens, a legume) was prevalent in the chicory monoculture. As these weed species represent different plant functional groups, they may have caused confounding effects on soil biotic and abiotic properties which, in turn, may have diluted treatment effects.

Secondly, soil heterogeneity may have contributed to the variability of our weed seed mortality. Spatial differences in soil microbiota, soil texture, porosity, and nutrients, likely variable within a plot due to inherent baseline soil characteristics as well as the uneven forage crops stands, may have created some pockets of soil where conditions promoted seed mortality and some pockets that permitted seed persistence. For example, mortality of subsamples from the same plot and timepoint were often highly variable (data not shown). Averaged across the plot and across treatment, these key fluctuations – possibly due to hyper localized conditions – were lost. It is important to note that we cannot determine the mode of mortality of the seeds in our experiment, whether microbial infection, fatal germination, or the minor possibility of predation by soil insects that entered the mesh bag through tears and root holes. Soil heterogeneity could have played differing roles across multiple modes of mortality. For example, localized pockets of soil N could have promoted fatal germination and/or microbial infection (Mohler et al. 2018; Davis 2007).

Lastly, we may not have detected treatment effects since we managed all the perennial treatments the same instead of individually optimizing the production for yield. Soil in orchard grass monocultures was significantly warmer than other treatments – including alfalfa monoculture – and this corresponded to low orchard grass biomass yields as more sunlight was directly reaching the soil surface (Appendix Figure A.3, Figure 2.4). This poor yield was likely due to nitrogen fertilizer deficiency. The N recommendation for orchard grass is 168 kg N ha-1 per year (Hall 2000); however, we applied a much lower rate (56 kg N ha-1) since we applied the same N-P-K fertilizer to all treatments. We did not want to manage treatments individually as this would be a confounding factor that could mask plant effects, and we also wanted supplemental N to be low to encourage biological N-fixation in alfalfa. Therefore, the orchard grass stand was sparse as it was not managed to production standards.

While the seed microbiome did not vary across perennial forage treatment, we did see that the microbiome was associated with weed seed mortality. The first principal coordinate of both bacterial and fungal communities was associated with A. powellii mortality and that the seed microbial communities within seed samples that had a high level of mortality differed from those that had low mortality. It is important to recognize that our findings only establish associations, and not a causal relationship with weed seed mortality. Microbes inside the high mortality seeds may not have necessarily been directly involved in the death or decay of the weed seeds but rather could have simply colonized a new environment (the injured or dead seed) and interacted with other microbes. Those microbes could be simply interacting with other microbes in the seed environment, and microbial competition could be driving shifts in the microbiome coinciding with, but independent of, seed mortality. Our microbiome approach to pathogenicity acknowledges that simply the presence of a known pathogen does not equate to mortality as there likely will be reductions in beneficial microbes as well as certain activation factors that shift a pathotroph-saprotroph-symbiotroph towards pathogenicity.

Education & outreach activities and participation summary

Participation summary:

- In summer 2026, we anticipate submitting a second paper to Journal of Applied Ecology about how the weed seed microbiome changes over time and how other factors (other than the treatment/perennial forages), affect the microbiome.

Completed:

- In December 2025, we submitted a paper to Weed Science about the effect of perennial forages on weed seed mortality and the weed seed microbiome. It is currently in review and is titled "Influence of perennial forage communities on weed seed mortality and seed microbial associations".

- In October 2025, PI Eckert finished translating and editing PSU Pesticide Applicator Educational Resources to Spanish. She worked with Maria Gorgo-Simcox, a Latinx PSU extension agent as well as 2 other native spanish speakers who were also graduate students at PSU. Their first educational course with the material occured in November 2025.

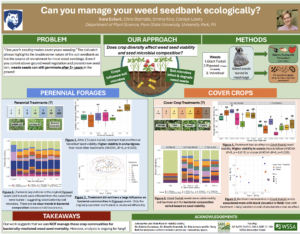

- In February 2025, PI Eckert attended the PASA 2025 Conference (Lancaster, PA), and presented a poster for 2 days. One of the days of the conference focused on presentations in Spanish and she translated a 2pg Pigweed ID guide in Spanish in collaboration with Dr. Lynn Sosnoskie at Cornell University.

- On August 14, 2024, during Penn State's Ag Progress Days event, PI Eckert presented preliminary data from this research project at the PA Forage and Grassland Council's tour of our research plots. About 40 council members (farmers and/or industry representatives) attended.

- On September 3, 2024, PI Eckert presented preliminary data in Spanish to visiting Latinx farmers during a research plot field tour sponsored by the Rodale Institute. About 6 farmers attended. *Yes, she also presented data from another SARE grant (about cover crops) at this event as well!

Project Outcomes

While our findings currently do not support an applied method for agroecological weed control through plant-based manipulation of the weed seed microbiome, we were able to uncover useful insights into microbes associated with weed seed mortality in the field. Additionally, we built upon previous research into microbially mediated weed seed mortality by utilizing more current Next Generation Sequencing techniques to view the weed seed microbiome with more detail. We will continue to investigate the weed seed microbiome, microbial colonization of the seed and seed mortality as we prepare our second publication.

Additionally, certain associations between abiotic conditions and seed mortality highlight the potential for seed mortality to be accelerated through soil fertility management. For example, we found frequent negative associations between soil cation concentration (K, Ca, and Mg) and weed seed mortality. Few studies have directly manipulated soil abiotic conditions (soil nutrients, soil moisture, and temperature) to examine their effects on seed mortality in soil (Davis, 2007).

Understanding whether specific soil amendments accelerate weed seed mortality would improve weed seedbank management, and future work should explicitly test which soil abiotic conditions and amendments influence the mortality of seeds in the soil seedbank.

Through my Master's thesis work on this project, I realized that I wanted to continue my work in sustainable agriculture, if not in the research realm. My time presenting to farmers through extension and outreach events for this project and other side projects made me realize that I wanted to be more hands on with my career and work directly with farmers. I graduated from PSU in August 2025 and am currently working for a consulting company in PA that helps farmers to reduce erosion and nutrient runoff through precise manure management, structural changes on the farm as well as cropping system changes. I often encounter opportunities to add in small tidbits of information about perennial forages and the weed seedbank. After all of my Master's work, I have a greater appreciation for all the research that goes into purely one table or guideline in a technical manual or the PSU Agronomy Guide. Others may take this for granted but I understand the hours of work needed to produce something that, while never perfect, it the best that we have with the research we have at the time.

Additionally, through all my presentations and networking on campus, I now know a great team of researchers and extension agents that I reach out to if questions arise in my current position. One of the best benefits of working on this project has definitely been the personal connections that can support collaborative work in the future.