Final report for GW23-255

Project Information

Dryland cropping systems are often water-limited in the northern great plains. Increasing soil-moisture retention is critical to support crops throughout the growing season, especially in times of drought. Stripper header technology, a new harvesting method that leaves full length stubble intact in the field, could improve soil water capture and water-use-efficiency (WUE) by obstructing wind, trapping snow, and decreasing evaporation. This research aims to assess the differences in snow-trap potential and WUE of pulse crops planted in two scenarios: traditionally combined short cereal stubble (<6 inches) and full-length cereal stubble harvested via a stripper header. Results from this research will be shared with producers and extension personnel via outreach programs and eventually a MontGuide.

- Investigate temporal aspects of snow trap and in-season water capture and use comparing very tall to short stubble.

- Inform producers on the value of stripper header technology to help achieve sustainability goals.

Fall 2023:

Producer engagement – producers were identified for collaboration and field sites were established. In November 2023, 12 Sentex soil moisture sensors were installed at each field location (Diekhans’ of Geraldine, MT, and Grove’s of Moccasin, MT). The sensors were left in the ground for the duration of the winter until spring planting, recording moisture and temperature measurements at the following depths: 2, 6, 10, 14, 18 and 22 in.

Winter 23-24:

Snow core samples were taken twice during the winter at each location. Sampling dates were as follows: January 22 and February 20, 2024.

Spring 2024:

Sentex sensors were removed on April 9th prior to pulse crop planting to avoid any damage caused by farm equipment. Immediately following planting, the sensors will be reinstalled for the duration of the growing season to provide a temporal pattern of soil moisture during the growing season.

Summer 2024:

Sentex sensors will be removed one week prior to pulse crop harvest, where 3-square-meter yield samples will be collected by hand. Additionally, field-scale yield data will be collected from the producers’ combines. Both types of yield data will be analyzed to compare pulse crop WUE between short and tall stubble plots.

Cooperators

- (Researcher)

- - Producer

- - Producer

Research

Research Methods and Analysis:

Initial soil moisture content was measured at the study sites with a Paul Brown probe on 11/8/23 so that the over-winter soil water gain can be accounted (Brown 1959). Diekhans’ farm consists of a 160-ac field divided in half for each stubble height where samples will be taken with short and tall stubble for comparison. Grove’s farm consists of a single field (120-ac) comprised of six-100 yd wide strips of alternating short and tall stubble. A statistical procedure called pseudo-replication will be used for determining sampling locations from a 100-yd grid pattern (Bricklemyer et al. 2007).

Snow cores were taken via a Federal Snow Sampler (Fig. 1) at two different dates (Jan. 22 and Feb. 20) during the winter to measure snow-water equivalence (SWE) and snow depth to assess how snow water storage varies between fields with short and tall stubble. At the emergence of spring once the snow has melted, soil moisture was again assessed with a Paul Brown Probe to determine the change in soil moisture compared to the fall the measure stored water from the winter snowpack. Paul brown probing was limited to Diekhans’ location only as the Grove’s field site has a cobble layer at ~12 in in depth that the probes cannot penetrate.

12 Sentex soil moisture probes were placed in the soil for the duration of the growing season at five depths (2, 6, 10, 14, 18, 22 in) at each location, gathering soil moisture and temperature data than can then be compared between short and tall stubble heights. These probes are provided in collaboration with Dr. Paul Nugent through his grant Quantifying the spectral response of specialty crops (pulses) to soil acidity, funded by the Specialty Crop Block Grant (SCBG) program. Pulse crop yields were measured at harvest to assess any differences between the pulse crops planted in short stubble versus tall stubble and to explicitly calculate WUE. WUE, in the context of this experiment, is calculated as dry matter yield divided by soil water depletion plus the total precipitation that occurred between seeding and harvest dates.

Pulse Crop Yield Analysis: Following physiological maturity of the pulse field and approximately one week prior to field scale harvest by the producer for spatial yield data, 3-square-meter yield samples were measured by hand at each location. Spatial grain yield data was also collected through each producers’ in-combine grain yield monitor, allowing for further comparison of stubble impact on yield.

The 2023-2024 winter in Central Montana was far below average in terms of snowpack and precipitation. Historic data (a 20-year average from 1997-2017), collected from NOAA, showed that Moccasin, MT, receives an average of 3.9 inches of water during the winter months (November-March). According to the Montana State Geographic Information Library, Central Montana only received 65% of its average annual snowpack during the 2023-2024 winter. The Central Agricultural Experiment Station, located in Moccasin, MT, received 1.9 inches of water from November 1st to March 31st, 2024, resulting in a very minimal snowpack and only 48% of the average winter precipitation.

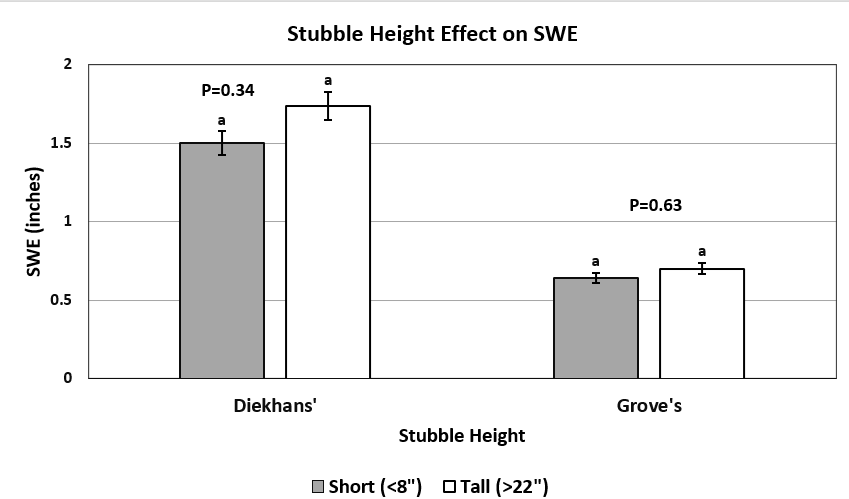

A linear regression model was fitted to predict the snow water equivalence (SWE) based on stubble height and sensor location using the following formula: SWE= β0 + β1 × stubble + β2 × sensor + ϵ. Measured SWE was numerically greater on average in tall vs short stubble, showing P-values of 0.34 and 0.63 for the Diekhans’ and Grove’s field sites respectively (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: SWE comparisons for short and tall stubble at both locations (Geraldine, MT = Diekhans; Moccasin, MT = Grove's).

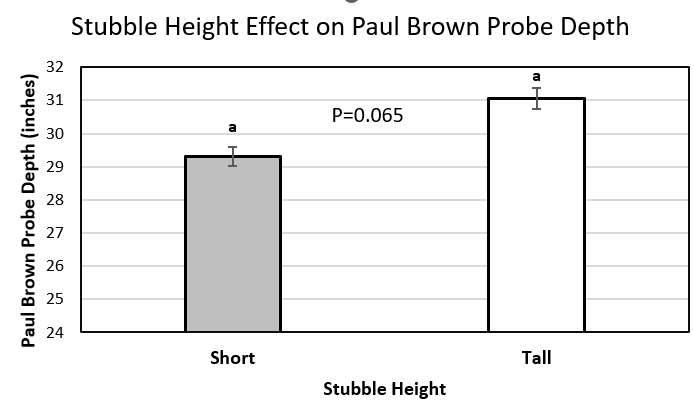

Additionally, a linear regression model (Moisture depth = β0 + β1 × stubble + ϵ) was fitted to assess any effects stubble height had on soil moisture depth. Paul Brown Probe measurements were negated at the Grove’s site as there is a shallow cobble layer (~12 in) that the probes cannot penetrate. A P-value = 0.065 was found from spring sampling when comparing the probe depths in tall vs. short stubble, with moisture depths averaging an additional 2-in in tall stubble (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Paul Brown Probe comparisons for short and tall stubble at Geraldine, MT.

Pulse Crop Productivity in Very Tall Wheat Stubble

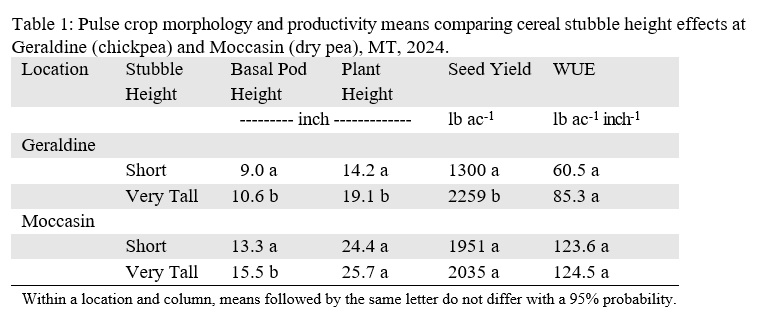

At Geraldine, measured chickpea parameters (basal pod and plant heights, seed yield, and water-use-efficiency) were markedly greater in very tall vs short stubble (Table 1). However, it was subsequently determined that the comparative sample areas were strongly confounded due to important in-field differences in soil parameters that were not apparent in the USDA SSURGO soil map. While both sample areas were defined as the same soil map unit, subsequent soil sampling showed greater clay and soil carbon content, and greater soil moisture in the portion of the field from where the very tall stubble chickpea samples were taken. Thus, it is not possible to say what proportion of increase, if any, was due to the very tall stubble microclimate or the superior soil properties compared with the portion of the field where chickpea samples were taken to represent the short stubble treatment. Also in the northern Great Plains, Cutforth et al. (2011) previously showed a linear increase (P = 0.10) in seed yield for chickpea as stubble height increased from cultivated to very tall (> 18 inch) research plots, with yields increasing from 1200 to 1430 lb ac-1. Further, these researchers reported an average seed yield increase of 9% across all pulses when grown in tall (14 inch) vs short (6 inch) stubble. While the producer of this field did not have quantitative data to share from machine harvest, he noted a drastic increase in yield between tall and short stubble, estimating >50% increase in seed yield in tall stubble (pers comm., C. Diekhans, Oct 2024). However, with such a drastic difference in yield measured at this study site in favor of tall stubble, it is likely that other factors influenced chickpea yield in addition to stubble height.

Morphologically, basal pod and plant heights increased by 1.6 and 4.8 inches in tall stubble, respectively (Table 1). Cutforth et al. (2002) showed during one study year that basal pod height was affected by stubble height, increasing across pulses by 1.8 inches when grown in tall (14 inch) vs. short (6 inch) stubble.

While difficult to quantify, increased height of basal pods increases harvest efficiency, saving producers time and wear-and-tear on machinery, and avoiding costly repairs and downtime associated with catastrophic equipment damage from ingesting stones or other obstacles in the combine at harvest. We consulted with several pulse growers to attempt valuation of a taller cutting height (Montana Pulse Crops Committee, 22 Oct, 2024; Montana Grain Growers Assoc., 3 Dec, 2024). Most agreed that avoided machine damage and down-time could represent the largest valuation but one producer in the audience at the Montana Grain Growers Association meeting quickly estimated a potential yield increase. His assumption was that if a taller stubble height permitted him to harvest just one more chickpea pod per plant containing a single seed compared with short stubble, with a standard crop density of 3 plants per ft-2, and typical seed weight of 14 oz per 1000 seeds, that would translate to a harvestable yield increase of 114 lb ac -1 , or $42 ac-1 more than in short stubble at a chickpea price of $22 bu-1.

At Moccasin, above-ground biomass, plant height, and seed yield of dry pea did not differ between stubble heights, while the basal pod height was 2.2 inch greater (P=0.016) in very tall stubble (Table 1). Again, the increase in basal pod height aids harvest efficiency and reduces damage to harvesting equipment and potentially increases harvestable yield.

While WUE at Geraldine showed an increasing trend (P = 0.07) in very tall stubble over short stubble, at Moccasin, no change in WUE was observed between stubble treatments (Table 2-5). Miller et al. (2002) assessed pulse crop adaptation in the NGP with over 20 location-years, and reported WUE range from 23 – 125 lb ac-1 inch-1 and 38 – 148 lb ac-1 inch-1 for chickpea and pea, respectively. The results from this study fell into the upper end of those reported ranges (Table 1). Additionally, Cutforth et al. 2002 found an 8% increase in WUE across all pulses grown in tall vs. short stubble.

There were clear visual differences in soil coverage for short vs. tall stubble. Shown below in Fig. 3 are two pictures taken on 14 May, 2024, at Moccasin, MT following spring seeding. It is visually evident that tall cereal stubble increased residual crop biomass which can be expected to provide greater protection from wind erosion and provide adequate ground coverage following pulse crop harvest. It is also noteworthy of the potential benefits of soil erosion protection by an increase in basal pod height.

Additionally, shown below in Fig. 4 are pictures taken 8 Nov, 2024, that display ground coverage post-harvest in the pea field at Moccasin. Note that very little pea stubble is evident; a majority of the soil coverage is due to the prior year’s cereal stubble, emphasizing the importance of proper stubble management for erosion control.

References

Bricklemyer, R.S., P.R. Miller, P.J. Turk, K. Paustian, T. Keck, and G. Nielsen. 2007. Sensitivity of the Century model to scale-related soil texture variability. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 71: 784-792

Brown, P.L. 1959. Soil moisture holds the key! Crops Soils, Vol. 11, no. 9. ASA, Madison, WI.

Cutforth, H., McConkey, B., Angadi, S. and Judiesch, D. 2011. Extra-tall stubble can increase crop yield in the semiarid Canadian prairie. Can. J. Plant Sci. 91:783-785

Cutforth, H.W., B. G. McConkey, D. Ulrich, P. R. Miller, and S. V. Angadi. 2002. Yield and water use efficiency of pulses seeded directly into standing stubble in the semiarid Canadian prairie. Canadian Journal of Plant Science 82(4): 681-686.

McMaster, G.S., Aiken, R.M. and Nielsen, D.C. 2000. Optimizing Wheat Harvest Cutting Height for Harvest Efficiency and Soil and Water Conservation. Agronomy Journal., 92: 1104-1108.

Meers, Scott Byron. 2005. Impact of harvest operations on parasitism of the wheat stem sawfly, Cephus cinctus Norton (Hymenoptera: Cephidae). Montana State Univ. M.Sc. thesis. 129 pp. https://scholarworks.montana.edu/xmlui/handle/1/1853

Michaelis, K. D., M.F. Virgil, and W.B. Henry. 2015. Crop Yields: Stripper Header Technology vs. Conventional Header Technology. Undergraduate Research Journal: Vol. 19 , Article 4.

Nielsen, D.C., P.W. Unger, and P.R. Miller. 2005. Efficient water use in dryland cropping systems in the Great Plains. Agronomy Journal 372:364–72.

Research outcomes

This WSARE Graduate student study may be best considered as preliminary field-scale evidence of changes in pulse crop morphology, productivity and water-use efficiency, and for minimizing soil erosion risk. Increase in basal pod height of pulse crops of 1 – 2.5 inches was the most consistent take-away from these two field sites and four site-years of a related plot-scale study (funded by the Montana Department of Agriculture Specialty Crop Block Grant). This carries potentially very valuable and important implications for harvesting pulse crops in dryland Montana.

Future research should explore the effects of very tall stubble on subsequent crop growth and soil protection across a much larger number of farms and field sites to learn potential regional differences in responses to stubble height. Nonetheless, this preliminary field-scale study (and related plot-scale research) suggests that stripper harvesting potentially represents a major advancement in crop productivity and soil protection in dryland Montana cropping systems. When these findings were reported at two pulse grower meetings in fall 2024, concern was raised by a leading pulse growers that the wetter, cooler microclimate of stripped cereal stubble could exacerbate disease problems in pulse crops. This is another aspect of cropping system change that should be studied.

Education and Outreach

Participation summary:

Education and outreach methods and analyses

Dr. Perry Miller, Dr. Adam Sigler and I will present research findings and recommendations from this project to a wide variety of audiences and professional groups, including producers, research faculty, fellow students, Extension personnel.

- MontGuide - MSU Extension MontGuides offer current information in a concise format on many agricultural topics. A MontGuide will be produced to inform producers directly of the economic and ecologic benefits of stripper headers. After MontGuides are published, there are a variety of outreach options through MSU Extension (direct mail to county offices, presentation at agent updates, etc.) to get the information to county Extension agents for distribution.

- Northern Pulse Growers Association annual meeting - The Northern Pulse Growers Association (NPGA) is a membership organization representing Montana and North Dakota pulse producers that diligently works to develop new markets, coordinate research, and educate growers on the pulse industry. Results from this research will be shared and distributed among stakeholders and producers at this function.

- Montana Grain Growers Association annual meeting - The Montana Grain Growers Association is recognized as a grain industry leader and is the only organization dedicated solely to representing the interests of Montana wheat and barley producers. Results from this research will be shared and distributed among producers and stakeholders at this function.

- October 2024. Perry Miller presented the preliminary findings of this research to the Montana Pulse Crops Committee at Bozeman, MT.

- December 2024. Perry Miller presented the same at the Northern Pulse Growers' Pulse Day in concert with the Montana Grain Growers Association at Great Falls, MT.

- January 2025. Ryan Barnes presented the same at the Montana Ag Business Association annual meeting at Great Falls, MT.

- July 2025. Undergrad student Eve Heeley-Ray and Perry Miller discussed the topic of stubble microclimate for pulse crop production at the College of Agriculture annual Field Day at Bozeman, MT.

- November 2025. Perry Miller presented this research in a webinar hosted by the Northern Crops Institute.