Final report for LNE20-405R

Project Information

The Chesapeake Bay Foundation is looking afresh at an ancient practice that has seemingly dropped from common use. Silvopasture offers an opportunity to improve animal comfort and performance, protect environmental resources, create more appealing landscapes, and diversify farm resources and income. Many landowners can perceive these benefits, however, managing these landscapes simultaneously for healthy trees, forage, and livestock is a challenge. In addition to the added complexity is the lack of information on how to design with trees to compliment the farm, and how to effectively get trees established in working pastures.

Information on designing silvopasture for farmers’ needs, within their budget and within the context of their landscape is lacking. To achieve the real economic and ecological benefits that come from silvopasture, it is imperative to develop a much more cost-effective means of tree establishment.

Throughout this project CBF designed and implemented a study to explore these very needs.

Research Objective

This project tested 8 different establishment techniques of bareroot trees in pasture on 5 farms over 3 years, tracking cost and survival rates, establishing a baseline for soil, forage quality and types, and comparing results. The information gained from this study will inform producers on how best to begin integrating silvopasture into their farm systems.

Implementation and Research

The Chesapeake Bay Foundation, Trees For Graziers (TFG, formerly called Crow and Berry), and five farms planted trees in livestock pastures to assess methods to cost-effectively combine trees with grazing. Each farm planted 120 trees of various species, including hybrid poplar, honey locust, redbud, tulip poplar, willow, and fruit (apple, peach, pear, and plum), depending on each farm’s goals.

The farms integrated trees into existing pastures to reduce livestock heat stress in the summer with shade, shelter them from the winter winds, and provide forage during the summer “slump” when many grasses are dry and in the winter with stock-piled feeds such as honey locust pods and fruit. The trees reduce livestock stress due to weather and reduce feed costs during periods when forages are most limited. The value of these trees will increase with more extreme weather, as they hold water in place during heavy rains and provide drought resilience. Investments in planting and maintaining trees should improve farm profitability over the long-term.

Outreach

CBF worked with participating farmers to share their motivations, experiences, challenges and successes over the three years through video. We compiled a series of how-to educational videos that will provide support and help guide decisions for other farmers interested in this practice. We also conducted annual pasture walks throughout the grant period, which encouraged farmer-to-farmer education and connections.

Silvopasture is a unique but underused integration of trees within a farm system. Most farmers recognize the benefits of trees for livestock but are not aware of how to establish cost-effectively. This project will test 8 establishment techniques of trees in pasture on 5 farms over 3 years, tracking cost, survival rates, establishing a baseline for soil, forage quality and types, and comparing results. This will inform producers on how best to begin integrating silvopasture.

Throughout this project the Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF) and partners conducted research that assessed methods for farmers to establish productive trees in active pastures given predation, livestock damage, limited resources, and different types of forage and soils.

CBF and partner, Trees For Graziers (TFG), tested 8 different establishment techniques of bareroot trees in pasture on 5 farms over 3 years, tracking cost and survival rates, establishing a baseline for soil, forage quality and types, and comparing results.

Additionally, CBF and partners worked extensively to provide outreach and education on these practices. Outreach was conducted through a series of on farm demonstrations, field days, workshops and presentations, and the development of outreach and education materials. CBF worked with participating farmers to share their motivations, experiences, challenges and successes throughout the project.

Cooperators

- (Educator and Researcher)

Research

Project research assessed methods for farmers to establish productive trees in active pastures given predation, livestock damage, limited resources, and different types of forage and soils.

This project consists of tree plantings at 5 farms with 8 different treatments and designs associated with the type of farm operation. Since March 2020, we planted 120 trees at each farm. Trees consisted of hybrid poplar, honey locust, redbud, tulip poplar, and fruit (apple, peach, pear, and plum). The eight different treatments included: with and without wood chip mulch, plastic shelters with barbed wire, plastic shelters with electric fence, metal shelters, and no shelter but electric fence on both sides.

Average height and average diameter were measured for each species, forage quality and types, and survivability was monitored annually at the beginning, middle, and end of the project. Additionally, soil samples were taken from three areas within the silvopasture, and a control from a nearby pasture with similar conditions, but without trees, in 2020 and 2023. Samples were submitted to the Cornell Soil Health Lab, and soil organic matter and aggregate stability were compared.

See the description of each farm below.

Livengood Farm:

Livengood Farm manages a direct-to-consumer farming operation that supports 60-head of grass-fed Black Angus cow/calf along with open range turkeys. The 11-acre pasture is grazed 4 times a year to prevent overgrazing. In mid-September through mid-November turkeys are added to the pasture and when conditions permit, hay is cut from the pasture.

The pasture is well established with grasses and broadleaf plants. Orchardgrass, bromegrass, tall fescue, red clover, and white clover, dominate the ground cover. Also present are horse nettle, jimson weed, bindweed, and ground ivy. Four soil tests (3 Samples and 1 Control) were taken at the beginning of the project on August 10, 2020 and again near the end of the project on June 16, 2023 and submitted to the Cornell Soil Health Lab for analysis.

The research trees were planted on June 1, 2020, with 8 different types of treatments. Each tree was marked with a GPS point for easier and accurate data collection. On June 7, 2021, October 31, 2022, and May 17, 2023 data was collected on tree height, caliper, survival, and status of shelters. See updated map below.

|

Without Wood Chip Mulch |

|

|

Plastic Shelter, electric fence on both sides |

15 redbud |

|

Plastic Shelter, barbed wire around the shelter |

15 honey locust |

|

Metal Shelter, plus 2ft plastic shelter inside |

15 honey locust |

|

No shelter with electric fence on both sides |

15 hybrid poplar |

|

|

|

|

With Wood Chip Mulch |

|

|

Plastic Shelter, electric fence on both sides |

15 redbud |

|

Plastic Shelter, barbed wire around the shelter |

15 honey locust |

|

Metal Shelter, plus 2ft plastic shelter inside |

15 honey locust |

|

No shelter with electric fence on both sides |

15 hybrid poplar |

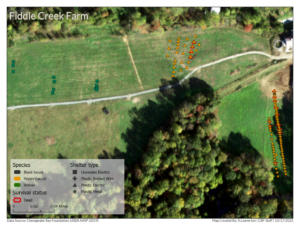

Fiddle Creek Dairy:

Fiddle Creek Dairy runs a small herd of 20 Jersey and Jersey cross cattle and sell their products locally. The 55-acre farm is rotationally grazed and managed for forage production. Trees dominate the banks of a stream that flows through the farm and a center cattle walkway permits cows to move from one pasture to another in the multiple pastures connected to the loafing barn. The cow/calves are rotationally grazed daily between milking and evenings, cows are fenced out of the stream corridor and instead of watering cows in the stream, each pasture has a water trough filled by water piped from the stream.

The pastures are recently seeded with a diverse mix of orchardgrass, bromegrass, red and white clover, rye grass, and tall fescue. The clover makes up 80% of the visible stand as observed in midsummer with plenty of butterflies enjoying the blossoms. In 2023, there was sweet clover, triticale, annual rye grass, and tall fescue, and still many butterflies and praying mantises. Four soil tests (3 Samples and 1 Control) were taken at the beginning of the project on August 10, 2020 and again near the end of the project on June 16, 2023 and submitted to the Cornell Soil Health Lab for analysis.

The research trees were planted on April 6, 2020 within a much larger silvopasture planting. On June 10, 2021,September 27, 2022, and May 17, 2023 data was collected on tree height, caliper, survival, and status of shelters. Each tree was marked with a GPS point for easier and accurate data collection. This farm showed higher quality grass in the shade of trees. See updated map below.

|

Without Wood Chip Mulch |

|

|

Plastic Shelter, electric fence on both sides |

15 honey locust |

|

Plastic Shelter, barbed wire around the shelter |

15 honey locust |

|

Metal Shelter, plus 2ft plastic shelter inside |

15 honey locust |

|

No shelter with electric fence on both sides |

13 willow and 2 hybrid poplar |

|

|

|

|

With Wood Chip Mulch |

|

|

Plastic Shelter, electric fence on both sides |

15 redbud |

|

Plastic Shelter, barbed wire around the shelter |

15 honey locust |

|

Metal Shelter, plus 2ft plastic shelter inside |

15 honey locust |

|

No shelter with electric fence on both sides |

15 hybrid poplar |

Rising Locust Farm:

Rising Locust Farm is a 20 acre, direct to consumer marketing farm with 12 head of Highland cow/calf, 8 hair sheep, and 30 layers rotating through the pasture 5-6 times per year depending on weather and available forage. The perimeter fence is multiple strand high tensile electric and the grazing sections are separated by temporary posts with a single strand of electric. A seasonal stream is protected in the middle of the pasture with an improved livestock stream crossing and a riparian buffer.

The pasture has an equal mix of orchardgrass, brome, and fescue accompanied by red and white clover. In 2023, orchard grass dominated, along with a mixture of fescue, bromegrass, chicory, bluegrass, white and red clover, and dandelion. Four soil tests (3 Samples and 1 Control) were taken on August 10, 2020 and again on May 19, 2023 and submitted to the Cornell Soil Health Lab for analysis.

The research trees were planted in already established (though young) silvopasture plantings on June 2, 2020. On June 9, 2021, and September 27, 2022, and May 19, 2023 data was collected on tree height, caliper, survival, and status of shelters. Each tree was marked with a GPS point for easier and accurate data collection. See updated map below.

|

Without Wood Chip Mulch |

|

|

Plastic Shelter, electric fence on both sides |

15 honey locust |

|

Plastic Shelter, barbed wire around the shelter |

15 honey locust |

|

Metal Shelter, plus 2ft plastic shelter inside |

15 honey locust |

|

No shelter with electric fence on both sides |

15 hybrid poplar |

|

|

|

|

With Wood Chip Mulch |

|

|

Plastic Shelter, electric fence on both sides |

15 honey locust |

|

Plastic Shelter, barbed wire around the shelter |

15 honey locust |

|

Metal Shelter, plus 2ft plastic shelter inside |

15 honey locust |

|

No shelter with electric fence on both sides |

15 hybrid poplar |

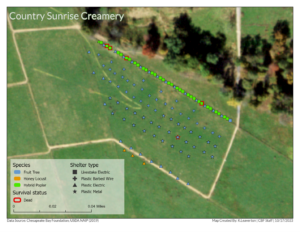

Country Sunrise Creamery:

Country Sunrise Creamery is a direct-to-consumer raw milk dairy farm with 80 head of Holstein and crossbred cows and calves, with 120 acres, mostly in fenced pasture. Cattle are rotationally grazed, with rest periods of 35-50 days between rotations. Some minimal supplemental feed, and more in the winter, is needed. The goal is to manage the farm without outsourcing hay and for the silvopasture planting to become a small orchard.

The pasture slopes at a 5-8% incline to a stream and fence and contains a diverse mixture of cover crops with about 20 different species. The most common species in 2020 were orchard grass, buckwheat, red and white clover, millet/sorghum, beans, and dandelion. In 2023, the species included: Orchard grass perennial ryegrass, perennial bluegrass, red and white clover, horse nettle, alfalfa, thistle, burdock, curlydock, chicory, plantain, dandelion, milk thistle, lambsquarter, goldenrod, Queen Ann’s lace, timothy, bromegrass, and ground cherry, along with a plethora of butterflies and other pollinators. Four soil tests (3 Samples and 1 Control) were taken on August 10, 2020 and May 22, 2023 and submitted to the Cornell Soil Health Lab for analysis.

The research trees were planted within a 4-acre orchard of apples, peach, pear, and plum on April 1, 2020. On June 7, 2021, September 26, 2022, and May 22, 2023 data was collected on tree height, caliper, survival, and status of shelters. Each tree was marked with a GPS point for easier and accurate data collection . See updated map below.

|

Without Wood Chip Mulch |

|

|

Plastic Shelter, electric fence on both sides |

15 apple, peach, pear, plum |

|

Plastic Shelter, barbed wire around the shelter |

15 apple, peach, pear, plum |

|

Metal Shelter, plus 2ft plastic shelter inside |

15 apple, peach, pear, plum |

|

No shelter with electric fence on both sides |

15 hybrid poplar |

|

|

|

|

With Wood Chip Mulch |

|

|

Plastic Shelter, electric fence on both sides |

15 apple, peach, pear, plum |

|

Plastic Shelter, barbed wire around the shelter |

15 apple, peach, pear, plum |

|

Metal Shelter, plus 2ft plastic shelter inside |

15 apple, peach, pear, plum |

|

No shelter with electric fence on both sides |

15 hybrid poplar |

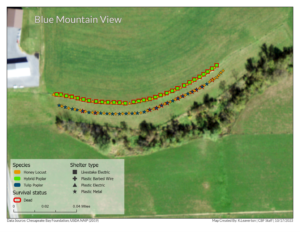

Blue Mountain View Farm:

Blue Mountain View Farm is a dairy farm with a 100 head of Jersey, Holstein, Swedish cattle mixed between heifers and dry and lactating cows. It is an organic certified dairy operation and part of a cooperative. Cattle are rotationally grazed, but only around 30% of feed comes from pasture. The farm is double cropped with corn, rye, and alfalfa.

Soils are mostly Berkshire and the silvopasture area has a slight slope towards a riparian buffered stream. The landowner designed the test area with diversity, potential timber, as well as the wildlife value in mind. The pasture was predominantly orchard grass with an equal mixture of red and white clover with some chicory, plantain, queen ann’s lace, and alfalfa in 2020. It was mostly orchardgrass, ryegrass, alfalfa, red clover, white clover, chicory, plantain, and bluegrass in 2023. Four soil tests (3 Samples and 1 Control) were taken on August 10, 2020 and again on May 25, 2023 and submitted to the Cornell Soil Health Lab for analysis.

The research trees were planted on June 3, 2020 with mostly honey locust, hybrid poplar and tulip poplar. On June 9, 2021, September 26, 2022, and May 2023 data was collected on tree height, caliper, survival, and status of shelters. The live stake hybrid poplar plantings did not survive the following drought. Each tree was marked with a GPS point for easier and accurate data collection. See updated map below.

|

Without Wood Chip Mulch |

|

|

Plastic Shelter, electric fence on both sides |

15 tulip poplar |

|

Plastic Shelter, barbed wire around the shelter |

15 honey locust |

|

Metal Shelter, plus 2ft plastic shelter inside |

15 honey locust |

|

No shelter with electric fence on both sides |

15 hybrid poplar |

|

|

|

|

With Wood Chip Mulch |

|

|

Plastic Shelter, electric fence on both sides |

15 tulip poplar |

|

Plastic Shelter, barbed wire around the shelter |

15 honey locust |

|

Metal Shelter, plus 2ft plastic shelter inside |

15 honey locust |

|

No shelter with electric fence on both sides |

15 hybrid poplar |

Tree Species

Trees are remarkably strong and resilient if given good care and conditions. Despite the myriad of challenges in the beginning of Spring 2020, including a much-delayed planting complicated by Covid-19, followed by several very dry spells during the hot summer months, the research plantings have overall done remarkably well.

Rising Locust farm, Blue Mountain farm, and Livengood farm trees were planted outside the ideal time for tree planting June 1-3, 2020; ideally, trees are planted between mid-March and mid-May. The delay was due to high order volume and Covid-related precautions. This was then followed by a very dry period and affected the mortality rate especially for the bare root poplar plantings.

Despite the late plantings, honey locust showed high survival rates coupled with strong growth. There were a few instances where voles chewed off the base of trees causing mortality, however their survival rate was over 92%. Tulip poplar, hybrid poplar, and redbud had lower survival rates possibly due to quality of stock, long storage, and late planting. These early planting setbacks should be taken into consideration when evaluating the overall success of establishing trees in these pastures.

Different types of Treatments

Trees had the highest survival rate with plastic shelters and barbed wire although with timely planting and high quality tree stock the survival rate within the other shelters would likely be higher.

Observation with the success rate of treatments to withstand cattle, sheep, turkeys, and chickens varied between farms. One observation with cattle and sheep is their tendency to rub against shelters with barbed wire and metal and the susceptibility of browse by sheep in the metal shelters. Both treatments did not fare as well in pasture with livestock compared to electric fencing, but the results were variable. The plastic shelters with electric fencing fared the best out of all the treatments, although it is one of the more expensive treatments. See success rate below.

- 92.3% success rate for plastic shelters and electric fencing

- 92.1% success rate for plastic shelters and barbed wire around the shelter

- 80% success rate for metal shelters plus 2 ft plastic shelter

Mulching vs Not Mulching

Throughout the project trees performed better with wood chip mulch than without, and in other observations performed better than coconut mats. Even though wood chips break down in about a year, they presumably help the soil retain moisture longer and create a hospitable fungal environment that is crucial for soil health. Wood chips also appear to provide less vole habitat than coconut mats. At three out of five farms, the mulched treatments had significantly less mortality than their non-mulched counterparts, indicating that mulched treatments increase survivability. An unexpected occurrence with chickens that follow larger ruminants in grazing rotation was observed. Chickens tend to scratch at the mulch around trees, in most cases eliminating all mulch in the research area. This happened at Rising Locust Farm, in essence creating a scenario where no trees had mulch.

Soil

Soil organic matter did not significantly change during the study. Three of the five farms saw significant increases to aggregate stability between 2020 and 2023. These farms also had large improvements in aggregate stability in the control samples in nearby pastures without trees. However, since there was only one control sample per farm, it wasn’t possible to determine if there was a statistically significant difference between the areas with and without trees.

Cost of Treatments

|

Treatment options |

Treatment price per tree |

Labor Costs |

Tree Seedling |

Cost Range for each Treatment |

|

Without Wood Chip Mulch |

||||

|

Plastic Shelter, electric fence on both sides |

$11 - $13 |

$14 - $16 |

$5 - $8 |

$30 - $37 |

|

Plastic Shelter, barbed wire around the shelter |

$5 - $7 |

$14 - $16 |

$5 - $8 |

$24 - $31 |

|

Metal Shelter, plus 2ft plastic shelter inside |

$11 - $13 |

$14 - $16 |

$5 - $8 |

$30 - $37 |

|

Live stake, no shelter with electric fence on both sides |

$7 - $9 |

$10 - $13 |

$0 - $5 |

$17 - $27 |

|

With Wood Chip Mulch |

||||

|

Plastic Shelter, electric fence on both sides |

$12 - $14 |

$14 - $16 |

$5 - $8 |

$31 - $38 |

|

Plastic Shelter, barbed wire around the shelter |

$6 - $8 |

$14 - $16 |

$5 - $8 |

$25 - $32 |

|

Metal Shelter, plus 2ft plastic shelter inside |

$12 - $14 |

$14 - $16 |

$5 - $8 |

$31 - $38 |

|

Live stake, no shelter with electric fence on both sides |

$8 - $10 |

$10 - $13 |

$0 - $5 |

$18 - $28 |

Costs reported as a range from 2020 - 2022 when treatments were implemented. The prices were averaged from contractors and nurseries. Fruit tree prices not included, average seedling price for fruit trees was $15 - $25 in that time period. In subsequent work we have seen an increase in prices due to material costs and inflation.

Summary of Results:

- Plastic Plantra 6-foot tubes provided great protection from browse. The tubes then need protection from rubbing.

- Metal cages were difficult to assemble, and did a poor job protecting trees. Vegetation grew up inside of them, and it was difficult to get inside to pull weeds or check on trees. Limbs grew through though cage and were easily browsed, thus creating more of an incentive for livestock to push the cages over. They did allow more air flow, which is useful for fruit trees, but there is no scenario where we would really recommend the cages over vented plastic shelters, given the challenge of protecting trees inside the cages.

- Barbed wire around the plastic tubes didn’t deter cattle from rubbing, and they sometimes got tails caught. When the cattle yanked the tails to free themselves, they sometimes pulled the shelters from the stakes. This could present danger to both the trees and livestock. The goal had been to create a protection system where cattle can freely move throughout the system, and the farmer had more flexibility than what is permitted by electric fencing along a row of trees. But given the unreliability of this method, it can’t be broadly recommended.

- Electric fencing to protect trees works well, especially when the farm already has this as part of the grazing system. Trees can be planted along the fence line, or tubes can be wrapped in an electric line going from tree to tree, especially if the electric line is high enough for the animals to go under it so they can easily graze between the trees.

- During dry periods, some of the most productive forages were in areas where the trees are already producing shade. Morning dew might have been absorbed by the shaded forages before the sun dried it. This should increase as the trees grow and increase their shade.

- Survival results varied by farm. However, trees with wood chip mulch had higher survivability than their non-mulched counterparts on all farms.

- Bare root live stake plantings had the lowest survival, with almost none on the three farms where plantings were delayed until June due to logistics during the Covid pandemic. A very dry period followed, and these trees were most vulnerable. The two farms with more timely plantings had 14% and 15% survival of the live stakes, which is still low, but could be improved with the much taller stakes that are now available, as well as more timely planting. Trees For Graziers has since planted well over a thousand live stakes of willows and poplars, with heights of 10 or more feet, with very high survival rates, and can firmly confirm that if given the right conditions, this technique can do very well.

- Hybrid poplar and fruit trees saw the highest mortality rates across farms. Honey locusts, redbuds, and willows had the highest survivability. Elsewhere, TFG has seen very little difference in survival rates between poplars and willows when done appropriately, while honey locust trees are universally very hardy. In his case, the willows planted at Fiddle Creek were planted as true live stakes, and planted in the right time of year (early spring), whereas most poplars had been planted much later than they should have, and weren’t as large as they should have been, due to lack of access to sizeable stock.

For farms planning silvopasture projects, our recommendations include:

- Six-foot Plantra shelters, which come standard with a fiberglass stake, in combination with electric fencing, is our most effective means of protecting trees in active pastures

- Establish trees in phases, and adapt the system over time, to see which species and methods work well with each farm’s specific goals, needs, soils, climate, and livestock management.

- Plant a limited number of trees each year, because they will need maintenance until they are beyond the reach of grazing animals and strong enough to resist rubbing and toppling.

- Maintain a high canopy, such as by pruning the lower sections of trees, so the shade shifts throughout the day. This facilitates even grazing since the animals move.

- Aiming for about 30% shade maintains forage while providing adequate shade. Hybrid poplar and willow grow quickly to provide fast shade. They could be mixed with species that provide additional benefits.

Silvopasture holds great potential to help farms improve overall profitability, especially with the increasing frequency and severity of extreme weather. Trees can help keep animals cooler in hot weather, protect from high winds, and provide feeds during periods when there are normally limited feed supplies, such as the winter and driest periods of summer when supplemental feeds are most expensive. Livestock will experience much lower stress, and thus improving production, when they are more comfortable in the weather.

Like most agricultural practices, there isn’t a single methodology that will work for every farm. The tree species used will depend on the farmers’ goals, whether they be supplemental timber, fruit or nut production to diversify the income stream, fodder to reduce feed costs, or simply shade. Hybrid poplar, black locust, and willow tend to grow quickly to provide shade in a shorter timeframe. Thornless honey locust will provide shade plus high energy pods that can provide valuable fodder for late fall and winter, but may grow more slowly than other species. Both black locust and honey locust can fix nitrogen, reducing the need for fertilizers. Also, whether to plant live stakes, small saplings, or larger trees will depend on local availability, budget, and quality of the trees.

The methods to protect trees from rodent damage, cattle rubbing, sheep nibbling, and other damage will depend on the livestock species and breed, and local conditions, such as wildlife populations and available electric fencing. Plastic shelters, six feet tall for cattle or five feet for deer and sheep, with either barbed wire or electric fence, protect trees during the establishment period. When electric fencing is available and practical to use, it is the preferred option since it more effectively deters livestock. Running the wire at six feet above the ground, rather than the more typical two to three feet, and wrapping the plastic shelters in polywire attached to the overhead wire, allows the livestock to move freely through the rows.

The trees in metal shelters with a two-foot plastic suffered more from browsing than trees in six-foot shelters. Also, performing aftercare on tree shelters is much more difficult and time consuming than aftercare on trees in Plantra shelters. Simply gaining access to the tree, and then re-installing the metal cage takes 2-3 minutes, versus 5 seconds for trees inside Plantra shelters. That adds considerably to the long-term establishment costs of silvopasture trees.

Mulch should be used on all plantings to protect from drought, support a fungal environment, and speed the tree growth. It is worth the cost and labor (about $2 per tree) to get some type of mulch in the critical first year or two years. We recommend untreated woodchips.

The shade in a silvopasture will help prevent forages from drying and becoming dormant during the hottest parts of summer. Although not many of the trees in this three-year study are producing substantial shade yet, the farms did notice that areas around some of the taller trees had higher quality forages for longer periods during dry months.

Because there is so much variability in the silvopasture practices on each farm, such as desired co-benefits of trees, livestock grazed, pasture conditions, ease of installing electric fencing, and other factors, starting slow with a few trees each year and adapting in the future is recommended. Establishing a small number of trees each year also allows the necessary maintenance when young. Shelters may be damaged, pruning may be needed, weeds may grow around trees providing habitat for rodents, or other factors.

Many farms will aim to have few or no branches on the lower part of the trunk where livestock may browse, and rather manage for a small canopy that starts high up on a tree, so that the shade moves throughout the day. This will facilitate animal movement and more even grazing, limiting over-grazing and manure concentrations in small areas underneath the trees.

Education & outreach activities and participation summary

Educational activities:

Participation summary:

We estimate attendance of approximately 1580 farmers, educators, and technical service providers at 14 events on farms of various stages of establishment, and 12 presentations, and other trainings. Participants learned about the benefits of silvopasture with shade in summer, windbreaks in winter, and diversified forages, and strategies for incorporating trees into pastures. They also learned about the pros and cons of various tree species, protection methods, and mulch types. We plan to continue to conduct additional outreach, such as sharing the videos that were produced with this grant.

More details on outreach activities below:

Curricula, factsheets or education tools:

- The Trees For Graziers website (https://treesforgraziers.com) now has 21 articles, all written since the start of this project, and many of them build off of learnings from the project. Additionally, Austin Unruh’s book focused on silvopasture establishment, The Grazier’s Guide to Trees: Taking Grazing to New Heights, draws on this research.

- Videos created by Chesapeake Bay Foundation featuring interviews with farmers sharing their experiences. Silvopasture videos are available on YouTube, accessible with the following links:

- Part 1: https://youtu.be/GAhd0f26XXU

- Part 2: https://youtu.be/x-Kr51kP0aw

- Part 3: https://youtu.be/L9rcycim3TQ

On - farm demonstration:

- Silvopasture walk at Country Sunrise Creamery (Nelson Martin) with about 20 farmers and 6 agricultural educators or service providers.

- Professional Technical Service Provider tour that visited Fiddle Creek, Rising Locust and Springwood Dairy . 12 farmers and service providers

- Trees for Graziers hosted a workshop for about 5 Organic Valley farmers on selecting the right tree species to achieve your farm goals

- Approximately 60 farmers and 5 agricultural conservationists learned about the benefits of incorporating trees into pastures, so livestock have shade in summer, windbreaks in winter, and additional forages, in a pasture walk at Springwood Dairy.

- On Farm Workshop – Forage and Forest: Tour a Third-Year Silvopasture, Fiddle Creek Dairy Organized by Pasa Sustainable Agriculture. 28 people attended, half farmers and half agricultural service providers.

- A grazing event hosted by Penn State at Fiddle Creek Dairy (Tim Sauder) with about 10 farmers and 12 agricultural educators or service providers.

Tours:

- Society of American Forester tour stop with about 30 foresters at Springwood Dairy (Dwight Stoltzfoos)

- Understanding Ag event at Springwood Dairy. Treees for Graziers lead an hour-long silvopasture tour with about 40 agricultural service providers.

- Attended event hosted by Pasa at Springwood Dairy, attended by PA Senator Bob Casey. Spoke with the senator and approximately 10 service providers about silvopasture.

Webinars, talks, and presentations:

- Trees for Graziers presentation to the Lancaster County Graziers group with over 200 farmers

- Trees for Graziers presentation and booth representation at an Organic Valley event in Belleville, PA with over 100 farmers and 15 agricultural service providers.

- PASA Sustainable Agriculture Conference 2022 – Silvopasture Panel: Reason, Realities, Results, moderated by CBF with NE SARE farmers and cooperators with about 60 farmers and 20 agricultural service providers.

- Trees for Graziers presentation at the Southeast PA Grazing Conference with over 250 farmers

- Webinar for the National Dairy Grazing Apprentice program with about 30 farmers and service providers

- Webinar for the Cornell New Farmers group with about 20 farmers

- Trees for Graziers booth and 2 speaking sessions and outreach on silvopasture at booth at Family Days on the Farm, with well over 100 farmers each year, mostly plain sect.

- An alleycropping event through Pasa, where Austin Unruh of Trees for Graziers spoke on silvopasture to about 16 farmers and 15 conservation professionals.

- Two-day silvopasture conference held in NY, organized by Brett Chedzoy. Trees for Graziers team attended, and shared learnings with about 50 farmers and 100 conservation professionals, including many foresters.

- Trees for Graziers answered producer questions on a panel with people from Working Trees.

- Trees for Graziers presentation to 30 producers at Utopihen Farms.

- 2023 PASA Sustainable Agriculture Conference, with three sessions on various aspects of silvopasture, with over 80 farmers and 50 service providers.

Workshop/field days:

- Trees for Graziers Field Day (2 days) with Organic Valley at Roman Stoltzfoos farm with about 50 farmers and 25 conservationists.

- Silvopasture Field Day: Trees for Your Animals and Land, Baken Creek Farm organized by PASA. 15 farmers and 6 service providers attended.

- Trees for Graziers provided a 3-day intensive training for 12 technical service providers working with silvopasture in November 2022, covering topics such as species selection, plan writing, protection methods for trees in pastures, and how to collaborate with other organizations to put together the funding needed to execute a project.

- Trees for Graziers hosted a workshop for about 10 Organic Valley farmers at Fiddle Creek Dairy, providing an overview of the three years of silvopasture there.

Learning Outcomes

CBF and Trees for Graziers has helped at least 25 farms establish silvopasture plantings since the start of this project.

We expect that all attendees at various events held throughout this project learned something about silvopasture based on their engaged discussion about tree species, types of protection against predation and livestock rubbing, and other issues. Although we did not conduct surveys to assess the level of learning, we do have reports that many additional farms are planting trees on their own pastures after attending presentations or seeing other farmers planting trees through this project.

Project Outcomes

Our partner, Trees for Graziers, was awarded a NE SARE Professional Development Program to train professionals to systematically develop and execute silvopasture plans with farmers. That grant built upon the knowledge gained from this project, and is allowing the continuation of important conservation work in this field.

Additionally, CBF, Trees for Graziers, and several other partners collaborated on a proposal to USDA NRCS Conservation Innovation Grant to install silvopasture practices on 10-15 farms in Pennsylvania and evaluate the environmental impacts, as well as evaluate the social and economic impacts of silvopasture on 15 -20 pre-existing silvopasture installations in the state. On-farm demonstrations, trainings, and farmer-to-farmer peer learning sessions will refine this popular practice standard in Pennsylvania - which has been suspended as an NRCS practice since 2018 - to ensure it can be reinstated and be successful for most farmers who apply and for NRCS staff to facilitate. This proposal has not yet been awarded at time of this report.

We expect to continue to collaborate with partners for future grant applications to build upon the results of this project.

All farmer cooperators are excited about the benefits they already see, and are expecting them to grow along with the trees. Most have expanded their tree plantings. Some of their neighbors that originally viewed their trees as an oddity or a waste of pasture are now planting trees in their pastures. One farmer stated that there are a thousand reasons to plant trees, and that the reason will determine the species and method.

Trees for Graziers has helped at least 25 farms establish silvopasture plantings since the start of this project. In addition, we hear that many additional farms are planting trees on their own after hearing presentations or seeing other farmers planting trees. We believe that this region may have the most planted hardwood silvopasture in the United States.

Although silvopasture is an ancient practice, much more research is needed to adapt this practice for the 21st century, with a changing climate, production methods, and market demands. Further study is needed to assess which tree species work best with livestock grazing, and produce other co-benefits, such as additional income streams or diverse feedstuffs.

We cannot assume that this research showed that redbuds and tulip poplars are incompatible with silvopasture, or that live stakes will not survive in pastures, or that hybrid poplars require a specific shelter. This study showed that these may be true when poor quality bare root trees are planted months after their typical planting window, and before a prolonged drought. Given the circumstances, we unfortunately saw several false negatives in this study.

Experience would indicate that given proper care and healthy plants to start, survival rates in the 80-90% range should be expected. Outside of this research project, Trees for Graziers has begun growing their own live stakes, and planted over 1,000 live stakes, each 10-14 feet tall, at farms throughout the region. The results have clearly shown that live stakes can be directly planted into pasture, with added benefits of quick shade and reduced costs of tree shelters. Because the live stakes have plenty of strength and are tall enough that livestock can’t browse, they can be protected from rubbing and bark stripping with a much shorter and less expensive mesh guard. Electrified polywire is still needed. This method of quick regeneration merits much more research. A significant benefit is that the trees produce shade much more quickly, often in the first 2-3 years, so farmers and livestock benefit much more quickly.

Good and timely maintenance is critical to tree success in silvopasture. At the beginning of the project, we assumed that after establishing the trees, after care needs would be minimal, given that livestock would be keeping competing vegetation down. However, we need to schedule and budget regular aftercare visits in the first 3-4 years to address issues like vole damage, livestock damage, weeds inside of shelters, tree deformation as a result of livestock injury or growing strange within the shelter, etc. Vegetation control right around the tree is also critical. The more we can suppress competing vegetation, the better the trees will grow, and quicker they’ll get to a size where they can readily withstand livestock pressure.

Alternatives to barbed wire are needed in pastures where electric fencing is not practical. A tree tube with one or two heavy wooden stakes could also be tested.

Another innovation that should be tested is using trees as living fenceposts, such as a long-term fencing solution where the hardware is nailed to a board that is nailed to a tree, so that fencing hardware does not grow into the tree. Since fencing is an existing cost for livestock farms, and planting trees can cost less than installing new fence posts, farmers should save money while getting all the benefits from trees, like shade, windbreak, fertility, and carbon sequestration.

Additional research may show that interplanting trees with companion plants, such as false indigo bush, may protect the trees from livestock rubbing, reduce browse pressure, and fix nitrogen. Also, various mulching materials, such as compost, could be evaluated. Additional means to prevent voles from girdling trees are essential. Methods for protecting trees in equine pastures need to be tested, since their height makes it more difficult to protect from browse.