Progress report for LNE21-421

Project Information

Problem and Justification: Urban farmers are unique among agriculturalists as they operate on a smaller scale in settings with less biological diversity and have less pest management options. Members of the project team have conducted more than 300 farm visits in Buffalo and NYC to date and observed that growers are challenged by pests that are not typically significant in rural NY settings, like Harlequin Bug, Two Spotted Spider Mite, and Whitefly. While pests are universally problematic for all agricultural producers, challenges in urban areas are unique and include limited space, lack of scale appropriate IPM inputs, limited research, and historically minimal technical support from Extension and crop service providers.

Solution and Approach: Our solution is to recruit 15 farms in Buffalo and NYC to participate in on-farm demonstration trials. These trials will educate growers on sustainable, non-spray options that are economically and environmentally sustainable while contributing to the social mission of the farms. Furthermore, they will simultaneously be used to evaluate the suitability of certain controls (exclusion, biological controls, varietal resistance, intercropping) in an urban setting. Farmers and project team members will identify site-specific pest management needs and sustainable solutions will be implemented and evaluated. Data and experiences will then be shared with other farmers through virtual and in-person events. Evaluation will document adoption and impact of sustainable techniques by farmers .

There are urban farms located in every major city throughout NYS, and although educators have a clear idea of the predominate pests in Buffalo and NYC, urban farms in other cities may experience different pests or challenges in managing them. To assess the needs of the greater NYS urban agriculture community, an estimated 75 urban farms across NYS will be surveyed to assess their respective needs in pest management. The survey will focus on identifying the most challenging pests on urban farms, how pests are currently managed, and perceived benefits urban growers are getting from those practices. This data can in turn be used by Extension educators, crop service providers, and researchers to direct future research and education efforts.

As part of the project, we will develop a guide on sustainable pest management practices for urban farms. Findings from the on-farm trials will be included, as well as a review on the different types of pest management practices (mechanical, biological, cultural, etc.), and additional resources that farmers can turn to for pest management help. To reduce barriers to accessing this knowledge, this guide will be translated into three foreign languages. This translated resource can greatly improve the ability for ESL or non-English speaking growers to succeed in their farming endeavors and thus increase the diversity of urban and rural farming in NYS and across the Northeast.

15 farmers in Buffalo and NYC will see an increase in revenue of $2000/acre as a result of implementing sustainable pest management practices for urban agriculture; and/or report quantifiable improved success in their social missions such as number of youths gaining pest management skills or diverse audiences reached. Increase in revenue will be the result of higher quality vegetables, improved yields, and decreased labor on pest management and sorting. This project will reach a diverse farmer base including minority and female farmers, new and beginning growers, and youth.

Cooperators

Research

This project has on-farm research in a demonstration function. We do not anticipate statistically valid experimental design. However, research activities organized by pest management practice trialed will be reported in this section.

Project Note: In the second year of this project (2022), there was a seven-month gap in project management due to personnel changes. This resulted in limited communication and impact measurement for on-farm demonstration trials in Buffalo. In 2023, we conducted an urban farm scouting program with farms in Buffalo and Rochester.

Releasing Ladybeetles to Manage Cabbage Whitefly

At Red Hook Farms and East New York Farms in NYC, we trialed Delphastus catalinae ladybeetles as a biocontrol for cabbage whitefly (Aleyrodes proletella), the most damaging pest of brassicas at both participating farms as well as many other farms and gardens in NYC. Delphastus is routinely used for control of other whitefly species in greenhouse settings, but we found no published research investigating Delphastus for control of cabbage whitefly.

At both farms, 150 to 300 Delphastus adults were released on 7/1/21 and 7/15/21 in selected locations within kale and collard plantings under a section of row cover which the farmers removed 7 to 12 days later. Whitefly infestation levels were estimated on a 0 to 3 rating scale at the time of release, where 0 = no whitefly nymphs or adults present on leaf undersides and 3 = severe infestation and unmarketable leaves; ratings were taken throughout the planting, averaging the values of 6 leaves sampled at each location. Using a hand lens, 3 leaves at each sampling location were briefly scouted for presence of Delphastus adults or larvae. In 2022, we repeated the trial releasing Delphastus catalinae ladybeetles for control of cabbage whitefly (Aleyrodes prolotella) on the same farms.

In 2023, we repeated the trial releasing Delphastus catalinae ladybeetles for control of cabbage whitefly (Aleyrodes prolotella) at Red Hook Farms and Pink Houses Community Farm (East New York Farms). At Red Hook, this was done as a controlled experiment: 6 sections of a row of curly kale were covered in insect exclusion netting for 7 days, with one bottle of Delphastus (estimated 40 to 90 surviving adults per bottle) released under each of 3 sections, and the remaining 3 serving as the control plots. At Pink Houses, these were released later in the season. At the first order of Delphastus, no whiteflies had yet appeared at Pink Houses, perhaps due to an effective “Brassica Break” and a later Delphastus release was attempted.

Adjusting Soil pH to Manage Pillbugs

Several NYC urban farms reported pillbug (aka roly-poly, Armadillidium vulgare) damage on radishes and hakurei turnips in spring 2021, including Edgemere Farm, where marketability of spring radishes was reduced by at least 50%. The soils at all these locations were high in organic matter (>8% OM) with a pH of at least 7.0, in some cases above 7.5. Some research has suggested pillbug root-feeding activity increases with higher soil pH.

On 10/6/21, soil testing was done at Edgemere Farm on two rows which were to be planted into radishes and/or hakurei turnips in spring 2022. Elemental sulfur (to lower pH) was then applied to one of the rows at a rate of 1.5 lbs per 100 square feet. The other row was designated as a control with no sulfur added.

In spring 2022 before planting, elemental sulfur application was repeated on the test area at a rate of 1.5 lbs per 100 square feet. In June 2022, soil testing was repeated to measure soil pH and a pillbug damage assessment was conducted on radishes and turnips.

Taking a “Brassica Break” to Reduce Pest Pressure

Several of the most prominent pests of brassicas in NYC (cabbage whitefly, harlequin bug, and flea beetle) overwinter on brassica crops left standing throughout the winter for year-round harvest, a common practice of urban farms and gardens. Four farms participating in this project—and subsequently, at least three additional urban farms—implemented a period of at least two weeks with no brassicas present on the farm in winter or early spring of 2022; or, as we began calling it, a “brassica break.” In 2023, at least 9 farms reported implementing a “Brassica break” of some form.

Resistant Cucumber Varieties for Downy Mildew

The project team has noted downy mildew of cucurbits to be a significant disease on New York City, Buffalo and Rochester farms. About 1/3 of urban farmers surveyed in NYS reported Downy Mildew of cucurbits as a top disease on their farm. In 2023, two East New York Farms- Pink Houses Community Farm and UCC Youth Farm- trialed a downy mildew resistant cucumber variety (Brickyard) alongside non-resistant varieties (Longfellow and Marketmore 76).

Spotted Lanternfly Management

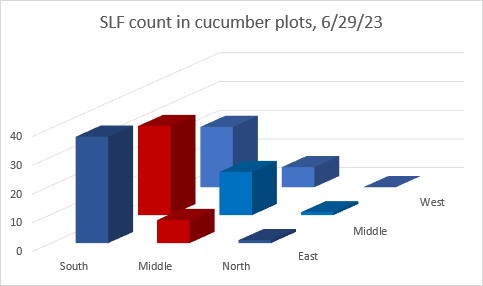

Between 2021 and 2023, spotted lanternfly (SLF) rapidly emerged as an invasive species in NYC. While SLF was already known to be a major pest of grapes, in 2021 the prevailing knowledge was that SLF does not damage vegetable crops. In 2022, we found SLF nymphs in high numbers on cucumbers and okra, with evidence of associated decline in the cucumbers (Figure 2). We also saw many SLF nymphs and adults in fruit trees, including figs, a common tree of NYC gardens, farms, and backyards.

In 2023, we trialed low-impact, low-cost SLF traps by using yellow insect sticky tape at two NYC farms. Some of the recommended SLF traps for trees had a history of excessive bycatch, including birds and frogs. We chose a narrow yellow tape (2” width) in hopes of avoiding this. On June 16, we applied individual sticky collars around the bases of cucumber and okra plants, using (supposedly) water-resistant cardboard tubes at Snug Harbor Heritage Farm. Additionally, we trialed applying tape directly to branches of a fig tree experiencing heavy infestation of SLF nymphs at Red Hook Farms.

Releasing Biocontrols and Other Tactics to Manage Aphids

From 2021-2023, several farms in Buffalo reported aphids in high tunnels on tomatoes and cucumbers as a major pest.

Urban Fruits and Veggies (UFV) is an urban farm on the East Side of Buffalo growing on ¼ acre in raised beds and in one greenhouse. They focus on mixed vegetable, herb and fruit production with plans to expand hydroponic and greenhouse production at future sites. In 2021, UFV reported high aphid pressure on peppers and brassicas. Aphid populations quickly built up on pepper and brassica transplants in the high tunnel prior to planting outside. We recommended releasing biocontrols to bring the population below the economic threshold. Ladybeetles and lacewing larvae were purchased and released.

In 2022 at UFV, we repeated releasing ladybeetles in the high tunnel for the control of aphids. Ladybeetles were released two times- once in July and once in August. They also tested using insect exclusion netting in the high tunnel and outside raised beds to help decrease pest pressure and support biocontrol release efforts.

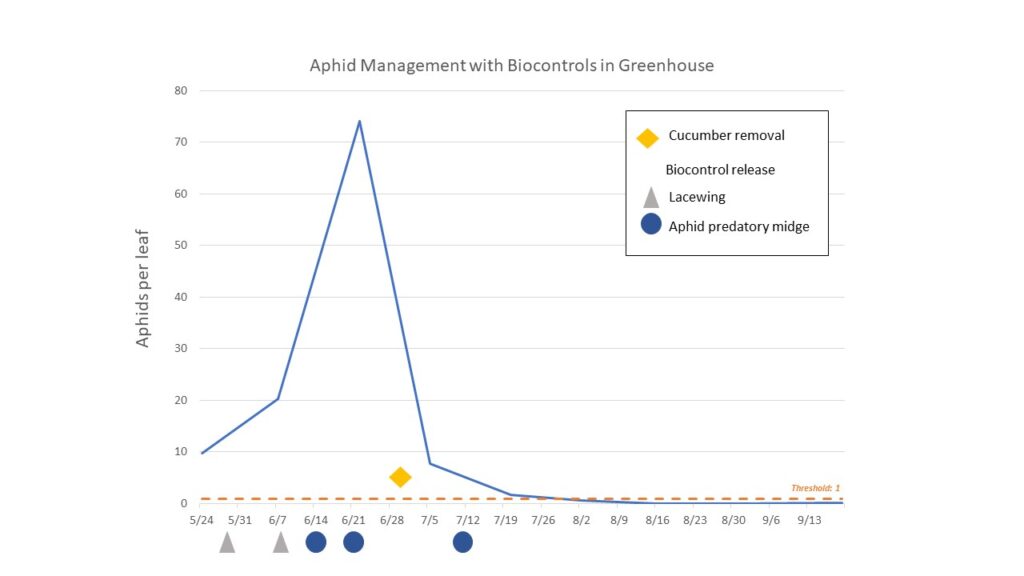

In 2023, UFV reported high aphid pressure on tomatoes and cucumbers in their greenhouse. Lacewing larvae (Chrysoperla rufilabris) were released 2x during end of May and early June to be used as a quick knockdown of the aphid population. Aphid predatory midge (Aphidoletes aphidimyza) was released 3x in middle of June and early July as a more sustained biocontrol approach throughout the season. According to Project Advisor, Carol Glenister, aphid predatory midge has been reported to reproduce successfully and maintain its population throughout the season. Prior to biocontrol introduction, we did an aphid count on greenhouse tomatoes and cucumbers on May 24. After biocontrol introduction, we did aphid counts 8x throughout the season every two weeks from June 7 through September 19. Aphid counts were done by counting the number of aphids on three randomly selected leaves per plant for six plants in cucumbers and six plants in tomatoes giving 36 leaves in total. Aphid counts are a measure of the average aphid number on a leaf (total aphid number divided by total number of leaves). Our scouting program used an action threshold of one aphid per leaf. Due to high aphid numbers, the farmer decided to pull the cucumber crop on June 29. After this, the remainder of aphid counts were done on only tomatoes.

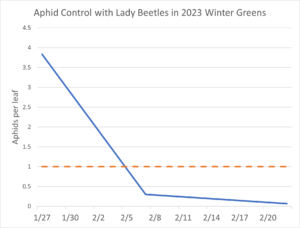

The Brewster Street Farm with Journey's End Refugee Services offers the Green Shoots for New Americans Program which facilitates urban farming opportunities on Buffalo’s East Side. The farm grows numerous culturally important vegetables from farmer participants immigrating from Nepal, Afghanistan, Bhutan, and more. In 2022, aphids were noted to be present in the farm high tunnel before spring planting. After planting, the farm released lady beetles 2x in June and poured diatomaceous earth 1x on soil to manage aphid populations. In addition, we trialed releasing Aphidoletes aphidimyza gall midges two times (once in July and August) for additional control of aphids. Infested crops were removed in early fall 2022, but some aphids remained most likely surviving on weeds and in the soil. In winter 2023, we worked with the farmer to manage aphids in their high tunnel winter greens production. We released two pints (18000 adults) of adult lady beetles (Hippodamia convergens) under row cover in plantings of winter greens and herbs on January 27, 2023. This rate is very high for the 1800 sq ft that we were treating. In future work, we hope to see similar results with lower rates, which would be more cost effective. Our scouting program used an action threshold of one aphid per leaf. We did aphid counts 4x throughout the winter from January 27 through March 10. Aphid counts were done by counting the number of aphids on three randomly selected leaves per plant for 20 plants giving 60 leaves in total. Aphid counts are a measure of the average aphid number on a leaf (total aphid number divided by total number of leaves).

The Massachusetts Avenue Project (MAP) farm located on Buffalo's West Side runs a year-round youth employment program building youth leadership skills through farming and other civic engagement programs. They grow a diversity of vegetables, fruits, flowers and herbs; they keep chickens and bees; and create numerous value-added products. In 2022, we trialed releasing Aphidoletes aphidimyza gall midges one time in the high tunnel for aphid control. After discussions with the farmer, we focused on trialing methods for managing flea beetles in 2023.

Using insect exclusion netting to manage cucumber beetles

Commons Roots Urban Farm is a one-acre urban farm in Buffalo producing diversified vegetables, fruit, flowers, and honey. In 2021, cucumber beetles were reported to be a significant pest on squash and cucumber. In 2021, we installed insect exclusion netting (ProtekNet Exclusion Netting, FIINTE3, 2x50-47 (Dubois Agrinovation)) on their caterpillar tunnel for exclusion of cucumber beetles on squash and cucumbers. Insect exclusion netting was applied prior to cucumber beetle emergence. Two Spotted Spider Mite (TSSM) damage was noted to be significant in the latter part of the 2021 season.

We were pleased to document during the 2022 growing season that Common Roots implemented insect exclusion netting on their caterpillar tunnel on their own to manage cucumber beetles on squash and cucumbers. Insect exclusion netting was applied prior to cucumber beetle emergence, and they grew parthenocarpic cucumber varieties. This adoption comes after an on-farm project demonstration in 2021. In addition, based off previous communication with project team members, Common Roots released a biocontrol mite predator, Phytoseiulus persimilis, one time early in the growing season to manage TSSM damage.

Swede Midge Management

An interesting development in this project was the severity of Swede Midge (SM), an invasive insect pest of brassicas, on Buffalo and Rochester farms. This has been an educational opportunity and here we dedicate an update on Swede Midge Scouting and Management plans:

SM has caused so much damage to brassica crops at Common Roots that in 2021 these farmers removed broccoli, brussels sprouts, cauliflower from their crop line-up entirely. In 2021, they rotated their brassica crops as far from the previous year’s planting as possible and covered everything with Proteknet exclusion netting. The netting had to be removed from crops (collards, kale) because the plants were getting too tall for their hoop set-up. Moving forward, they continue to grow the less-preferred brassicas under exclusion netting. Collards and the Russian types of kale are in the more-preferred category. Winterbor kales are less-preferred. Farmers will continue to make sure that transplants going under netting should be free of worm pests, and ground should be free of brassicas for at least 3 years.

The brassicas grown at UFV are primarily collards, kale, mustard greens, and kohlrabi. Collards have historically been the most effected by SM. In 2020, they moved all brassicas to a location outside of the city (Providence Farm Collective (East Aurora)) in order to get a marketable crop. In 2021, they brought collards back to the UFV site. Significant damage and larvae were observed early September 2021. In 2022, UFV focused on brassica crops in raised beds that have not have brassicas for past 2-3 years and used Proteknet exclusion netting. In 2023, SM damage was observed on collards again at the UFV site.

Brewster Street Farm has had significant SM damage prior to this project and SM was observed in the late Fall 2021 brassica planting. Intercropping is a common practice at the farm. Intercropping is done to 1) maximize use of raised bed space; 2) for support of beneficial insects; and 3) to receive benefits from companion planting. However, intercropping makes crop rotation difficult when each raised bed may contain crops from different families. SM built up on brassica crops in numerous raised beds across the farm. To manage SM, we implemented an integrated approach – remove late season brassica crop residue and discard, and apply H. bacteriophora entomopathogenic nematodes to the soil to try to knock down the overwintering population. The entomopathogenic nematodes will feed on a diverse range of soil dwelling pests, including SM. Nematodes were applied twice- once in Fall 2021 and in Spring 2022. Nematodes were watered in with a pump sprayer to raised beds. Raised beds were pre-wetted to allow better survival and movement of nematodes through the soil profile.

5 Loaves Urban Farm is a farm ministry connected to the Buffalo Vineyards Church. They have roughly ½ acre in production and grow on 4 separate lots on the West Side of Buffalo. They grow a diversity of vegetables, fruits, and herbs; they keep chickens and bees; and create numerous value-added products. The farm was noted to have SM damage on their brassicas in mid-summer 2021. Damage was quite extensive on kale, collards, broccoli, and cauliflower. SM damage was found on 2/2 lots those brassicas were grown on. Brassicas are grown under row cover, but the fabric is torn in numerous areas. In mid-Summer 2021, we began monitoring the population of SM on the main lot. SM pheromone traps were collected on a biweekly basis for 2 months – 7/30, 8/12, 8/28, 9/8. We recommended rotating away from brassicas where possible and prioritizing brassicas on the most recently acquired lot. In addition, we recommended to cover with insect exclusion netting. In 2023, 5 Loaves served as a scouting location and SM damage was noted on kale, broccoli, collards, and cabbage.

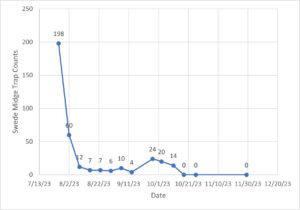

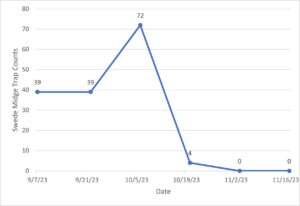

WestSide Tilth is a one-acre urban market garden farm in Buffalo producing diversified vegetables, herbs, and flowers. In 2023, SM larva and damage on collards was noted on June 16. The farmer reported struggling with SM on various brassicas including kale, kohlrabi, collards, and cabbage for the last few years with damage seeming to increase each year. We began monitoring the population of SM on the urban farm using two traps in July 2023. SM pheromone sticky cards were collected on a weekly basis from 7/20 until 9/13, then on a biweekly basis until 10/26, and the final sticky cards were collected on 11/29. The two traps were periodically moved to different beds with and without insect netting as crops were harvested and planted. One trap was moved into a collards planting under insect netting on Aug 16 and remained there for the duration of monitoring.

Foodlink Community Farm is a 1.6-acre urban agriculture campus in Northwest Rochester containing a commercial farm producing vegetables, fruit and honey, and a large community garden serving 70 multigenerational New American families. Extensive SM damage was noted at the end of June 2023, we noted unusual growth patterns, brown corky scarring, soft rot at the growing point in collards and kale. At the end of the season, the farmer reported losing four raised beds and over 100 lbs of brassica crops due to SM. In August 2023, we began monitoring the population of SM using one trap in a raised bed containing brassicas on the urban farm. SM pheromone sticky cards were collected on a biweekly basis for 3 months from 8/25 through 11/17.

The above case studies of Swede Midge support potential further in-depth work on this pest in urban settings.

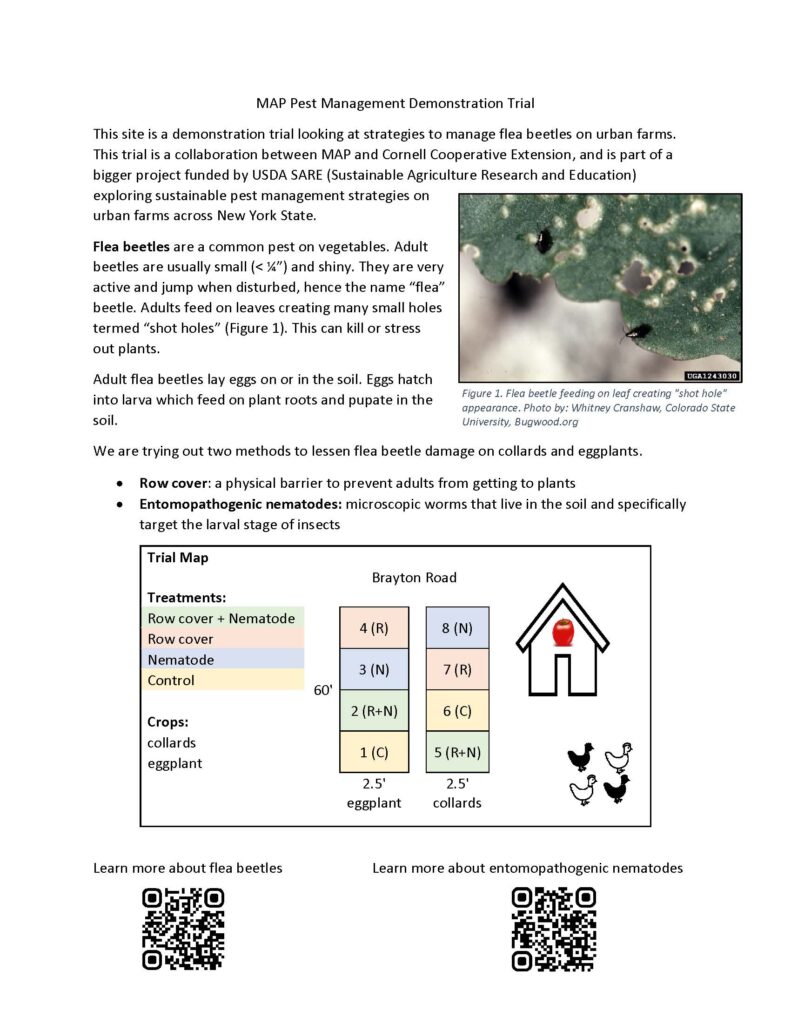

Using Row Cover and Entomopathogenic Nematodes to Manage Flea Beetles

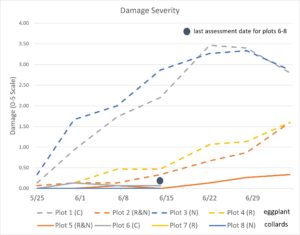

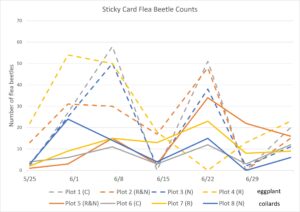

MAP farm manager reported flea beetles as a major pest. In 2023, MAP hosted a demonstration trial looking at strategies to manage flea beetles on collards and eggplant. There were four treatments tested: 1) row cover, 2) entomopathogenic nematodes, 3) a combination of row cover and entomopathogenic nematodes, and 4) an untreated control plot. The trial was set up and planted on May 17 (Figure 3). There were 18 plants in each plot at planting. Row cover used was 0.5 oz and put on at time of planting. Row cover was removed from eggplant plots on June 22 and from collards on July 5. A single entomopathogenic nematode species was chosen for treatment based off conversations with Project Advisor Carol Glenister. Steinernema carpocapsae is a sedentary ambusher species chosen for its ability to withstand lower soil temperatures and availability for purchase. Nematodes were applied in a water solution using a watering can at a rate of 5 million nematodes / 1600 sq ft on May 17 and May 25.

Nematodes were applied in the middle of the day on May 17 and nematodes were applied in the evening on May 25. A yellow sticky card was placed in the middle of each plot and counted for flea beetles weekly from May 25 through July 5. Flea beetle damage assessments were conducted weekly from May 25 through July 5. Damage severity was an average of the leaf damage rating for three randomly selected leaves per plant. Damage per leaf was rated on a 0-5 scale corresponding to the percentage of leaf with symptoms (0 = 0%; 1 = 1-20%; 2 = 21-40%; 3 = 41-60%; 4 = 60-80%; 5 = 80-100%). Our last damage assessment for three out of four collard plots took place on June 14. These plots plant loss due to a chicken feeding event. Harvest yields were measured regularly from July 5 through November 1.

Our work in this project is not pure research, as we are implementing natural pest management techniques that already have a demonstrated high potential for success. What is unique is the urban setting in which we adapt and deploy the management practices, as well as the site specific pests and practices. However, at some sites we are able to collect quantifiable data that provides a very applied research approach with the ultimate goal of demonstrating impacts to the farmers.

Releasing Ladybeetles to Manage Cabbage Whitefly

Scouting on 7/15/21 and 8/18/21 showed slightly less whitefly pressure near areas of Delphastus release. On one farm, there was a rating of 1.5 near the release location versus 2 to 2.5 at the other locations sampled. At the other farm, there was a rating of 2 near the release location versus 2.5 at most other locations scouted. Three Delphastus larvae were identified on collard leaves at one farm on 9/23/21, including clear evidence of cabbage whitefly predation. The presence of Delphastus larvae and evidence of cabbage whitefly predation, along with lessons learned about improving effectiveness of releasing Delphastus in outdoor settings and farmers’ stated interest in this biocontrol as an IPM strategy, suggested that we should expand on this trial in 2022.

In 2022, we trialed releasing Delphastus catalinae ladybeetles again on the same farms for control of cabbage whitefly (Aleyrodes prolotella). As in 2021, we found Delphastus larvae on brassicas (evidence of successful reproduction, since Delphastus are released as adults), with clear signs of predation of cabbage whitefly nymphs. However, as in 2021, we did not find conclusive evidence of a corresponding reduction in whitefly damage.

In 2023, at Red Hook, a count on August 11 showed no significant difference in whitefly adults or nymphs between treatment and control plots. Treatment sections had significantly fewer egg clusters at 26 per leaf, compared to 41 per leaf in the control sections. This squares with the Delphastus supplier’s comment to us that the species (nymphs and especially adults) preferentially predates eggs versus nymphs or adults. On the 18 leaves scouted in treatment sections, we found only 3 Delphastus larvae and 1 adult, and none in the control sections.

Several Delphastus larvae were identified on leaves about 3 weeks after the biocontrol release at Pink Houses in 2023. Though this was not done as a controlled experiment and it was unclear whether the ladybeetles were effective as a control. Overall, while we continue to find ample evidence that Delphastus predates on cabbage whitefly and reproduces successfully while doing so, it remains unclear how to effectively use Delphastus as a control for cabbage whitefly.

Detecting Parasitoid Wasp of Cabbage Whitefly

An unanticipated finding in 2022: In the process of scouting for cabbage whitefly predation and Delphastus, we noticed the presence of a parasitoid wasp (Figure 4) which very clearly appears to be parasitizing cabbage whitefly nymphs; the adult wasps were very common in the scouted plantings, with as many as 10 per leaf. The wasp resembles Encarsia formosa, a commonly purchased biocontrol of greenhouse whitefly, but we believe this to be Encarsia tricolor, which we subsequently learned has been observed as a naturally occurring cabbage whitefly parasitoid in Eurasia. A search of academic databases has so far turned up no other documented observations of Encarsia tricolor parasitizing cabbage whitefly in the Americas.

In Fall 2023, we found and collected more unidentified Encarsia specimens at Pink Houses Community Farm. None were found at Red Hook Farm, as in past years, possibly due to their more regular regime of spraying insecticidal soap to suppress whiteflies (once weekly after first appearance, with an improved nozzle and new battery-operated backpack sprayer). Adult Encarsia were collected in 90% ethyl alcohol and sent to a USDA ARS research partner (Michael Gates, housed at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C.), a taxonomist specializing in Encarsia, for identification. He reported that while the species is likely a close relative of Encarsia tricolor, it may be a previously undescribed species; he is securing a second opinion. If determined to be a new species, we intend to submit a paper to describe and name it. We brought some parasitized whitefly nymphs indoors and set up two insect rearing pens: one for Encarsia and cabbage whitefly together, and one for additional cabbage whitefly to provide a continual food source for the Encarsia. In late November, the whitefly population had increased enough to threaten the host plant’s health. On 12/1, the first confirmed Encarsia adult appeared. By 12/4, many more Encarsia adults had emerged, at least 4 per leaf. By 12/12, the whitefly population had crashed, with no egg clusters found in the rearing pen and very few adults remaining. Closer inspection showed that on some leaves, nearly every whitefly nymph had been successfully parasitized. While in a controlled environment, this demonstrates the potential of this Encarsia species to control cabbage whitefly.

Adjusting Soil pH to Manage Pillbugs

After the second sulfur application in spring 2022, the treatment area’s pH was measured at 6.8, compared to 7.2 for the control area. While pillbug damage was reduced in general compared to 2021 (Figure 5) (possibly due to drier weather), Edgemere found nearly no pillbug damage in the treatment area in 2022 (Figure 6), compared to 10-15% of radishes damaged in the control area (Figure 7). This early result shows promise in reducing pillbug feeding damage by reducing soil pH leading to increases in revenue by over $2000 per acre.

Taking a “Brassica Break” to Reduce Pest Pressure

In 2022, demonstration trials of a new approach to reduce brassica pest pressure was particularly successful. At all seven of farms implementing a brassica break, the first appearance of the previous years’ most significant spring brassica pests—cabbage whitefly, harlequin bug, or flea beetle—was delayed by two to seven weeks. This resulted in large increases in marketable product during brassica plantings’ head start. For example, at Kelly Street Garden, 163 lbs of collard greens were harvested before the first appearance of cabbage whitefly nymphs; the prior year, fewer than 35 lbs of collards were harvested before whitefly nymphs began affecting marketability. This 128 lb increase is over $350 more in revenue and amounts to over 23,000 lbs per acre and over $40,000 per acre in revenue.

In 2023, all 9 farms reported a later onset of cabbage whitefly, from 2 to 8 weeks. Two farms that used a modified Brassica break by leaving row cover on all brassicas until late June also reported a near absence of flea beetles, aphids, or harlequin bug until fall.

Resistant Cucumber Varieties for Downy Mildew

Both farms trialing a downy mildew resistant cucumber variety (Brickyard) alongside non-resistant varieties (Longfellow and Marketmore 76) saw straightforward results. Cucurbit downy mildew caused rapid plant decline in the Longfellow and Marketmore beginning in late July, with nearly no yield after August 15, while Brickyard continued producing until mid-September. Both farmers intend to expand use of DM resistant cucumbers in the future.

Spotted Lanternfly Management

In 2023, while trialing low-impact, low-cost SLF traps, NYC experienced two heavy rain events between June 16 and when we returned to check the traps on June 29 at Snug Harbor. The tape had come unattached from most of the cardboard collars. The cucumber traps also were insufficient due to many points at which weeds reached above the collars, providing alternate routes for nymphs to crawl onto the cucumber plants and the trellising. That said, there may have been some reduction in SLF nymphs in one treatment section (bottom center, or “East-Middle,” in Figure 8). On okra, plants with sticky tape collars average 1.3 SLF nymphs per plant on 6/29, compared to 1.6 per plant on plants without traps, possibly indicating some effectiveness, but probably not justifying the labor of attaching the traps.

However, at Red Hook, we did see promising results on the fig tree (Figure 9). Although we were unable to get a thorough count of nymphs on the branches, we observed that of the 6 branches protected by a sticky tape collar, only 1 had SLF nymphs present on 6/29, while the majority of neighboring branches had at least 10 nymphs per branch. Although only one nymph was actually seen stuck to the tape, we watched several nymphs approach the sticky tape, then turn around. Even when attempting to force the nymphs to cross the tape by “herding” them down the branch with a hand, when they reached the tape, they preferred to walk around or even over our hand rather than venture onto the tape. This suggests that yellow sticky tape may be effective as a low-cost barrier for keeping SLF nymphs off of trees; at least for fig trees, which have smooth bark that allows the tape to stay attached for several weeks.

Releasing Biocontrols and Other Tactics to Manage Aphids

With using an integrated pest management approach of releasing biocontrols and using insect exclusion netting in 2022, UFV reported increases in crop yields a with 25% increase in crop size, and an increase in crop quality and length of harvest window. UFV farm manager noted a reduction in labor time and costs. Prior to implementing these pest management practices, farm workers would spend 5 hours per week on pest management (observing, strategizing, handpicking) and after implementing these practices farm workers would spend 2 hours on pest management- net decrease of 3 hours per week. This equates to saving over $2200 on labor per year. In 2023, Aphidoletes aphidimyza larvae were observed feeding on aphids on cucumber leaves on June 22 (Figure 10). We saw a decrease in aphid numbers after 4 biocontrol releases and the removal of the cucumber crop (Figure 11). The UFV farm manager noted again a reduction in labor time and costs. The farm manager reported the plants were cleaner with less pests and less money having to be spent on pest control products. He reported saving roughly 15 hours a month during the growing season on pest management in the greenhouse due to the biocontrol release. This equates to saving over $850 on labor during the growing season in 2023.

In 2022, the Brewster Street Farm manager noted the diatomaceous earth possibly had negative effect on lady beetles. The farm manager reported these practices resulted in an increase in crop quality and increased harvest window of high tunnel tomatoes by 4 weeks. The farm manager shared they “would have had to pull all tomato plants in July [2022] if not for the biocontrols.” In winter 2023, lady beetles were still alive and reduced the aphid population by 98.2% by Feb 22 (Figure 12). On our final check on March 10, we did not see any aphids in the high tunnel.

At the MAP Farm in 2022, no impact was observed from releasing biocontrols. This can partly be due to more communication needed from project members. In 2023, we worked closer with this site and included them in our urban scouting program. After discussions with the farmer manager, we focused on trialing methods for managing flea beetles in 2023.

Using insect exclusion netting to manage cucumber beetles

At Common Roots Urban Farm in 2021, insect netting appeared to provide sufficient protection of squash and cucumber plants from cucumber beetles. However, the cucumber plants did suffer from lack of pollination due to 1) not being a parthenocarpic variety and 2) the exclusion netting further inhibited pollinators from entering the tunnel. To remedy this, Common Roots moved frames of bees into the tunnel. Pollination thereafter seemed adequate but noticeably less. Two Spotted Spider Mite (TSSM) damage was noted to be significant in the latter part of the season.

In 2022, Common Roots reported the insect netting appeared to provide sufficient protection of squash and cucumber plants from cucumber beetles. After releasing the biocontrol mite predator, farmers reported they noticed a decrease in TSSM damage and would have released the biocontrol a few more times but cost was prohibitive. Overall, Common Roots reported a 25% increase in cucumber yield in 2022. Prior to this project and implementing these sustainable pest management strategies, Common Roots reported $323 in cucumber revenue. In the second year of this project and after implementing these sustainable pest management strategies, Common Roots reported $1070 in cucumber revenue, a $747 increase in cucumber revenue over the course of this project. In 2023, the farmers at Common Roots took a break from farming to pursue other business opportunities.

Swede Midge Management

In 2021, Swede Midge (SM) was identified as a priority pest on Buffalo farms. In 2022, a few farms implemented recommended SM management strategies. In 2022, UFV reported practicing crop rotation focusing brassica crops in raised beds that have not have brassicas in them for past 2-3 years and used Proteknet exclusion netting. They did not notice significant swede midge damage in 2022.

At Brewster Street Farm, all raised beds affected by SM in the first year of this project had late season brassica crop residue removed and discarded. These beds were treated with Heterorhabditis bacteriophora nematodes in Fall 2021 and Spring 2022. In 2022, SM was still present on farm but less damage was observed compared to last year.

In 2023, we began monitoring the populations of SM mid-summer at two farms, WestSide Tilth and Foodlink Community Farm. At WestSide Tilth, we saw highest SM numbers in mid-July and the population decreases over the rest of the season with a small spike in late September and going dormant by the end of October (Figure 13). This aligns with typical SM population dynamics observed in our area. In New York, we see peak emergence of adult swede midge from overwintered pupae in late spring. The high SM population in mid-July corresponds the initial collards planting showing severe damage. The sharp decline in population we speculate is due to timely post-harvest crop destruction by the farmer. We did observe SM on sticky cards in the collards bed under insect netting which we speculate is due to SM already being present in the soil. In future work to manage SM at WestSide Tilth, we are interested in looking at variety selection, ground barriers, and delaying planting as possible management tools.

At Foodlink Community Farm, we saw moderate SM numbers at the end of August with a spike in early October which we speculate may be due to warm weather (Figure 14). The farmer saw pest management and educational value in monitoring the SM population. Based off our work in 2023, the farmer plans to stop growing Red Russian Kale and explore new brassica varieties that may be less appealing to SM. In addition, the farmer plans to continue using insect exclusion netting with brassicas, especially in areas that have not have brassicas grown in them for at least 3 years. The farmer shared the trap was a “great teaching tool working with community gardeners and tour groups. It fits in with the growing practices of the farm. It shows the pest is there and is helpful to keep track of pest pressure. It helps to illustrate the importance of knowing a pest’s life cycle when choosing management tools.” The farmer reported on average 25 people visit the farm weekly from school and community groups, with over 1000 people visiting the farm throughout the growing season.

Using Row Cover and Entomopathogenic Nematodes to Manage Flea Beetles

Eggplant plots without row cover initially showed higher damage levels than eggplant plots with row cover and eggplant damage levels appeared to be evening out among treatments as the season progressed (Figure 15). We hypothesize this could be due to plants growing more leaves. Eggplants showed higher damage levels than collards and flea beetle counts on sticky cards were consistently higher in eggplant plots (Figure 16). We hypothesize this could be due to flea beetle host preference. We believe we observed multiple species of flea beetles on plants and on sticky cards including the crucifer flea beetle, striped flea beetle and eggplant flea beetle. Flea beetles were present on sticky cards in each treatment.

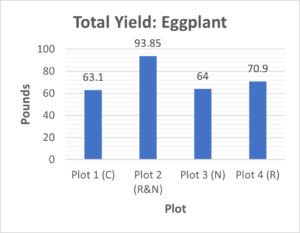

Eggplant plots with row cover produced higher yields than eggplant plots without row cover (Figure 17). Our two plots with row cover produced a total of 164.75 lbs and our two plots without row cover produced a total of 127.1 lbs. This farm reported selling a quart of African Eggplant (1 lb) for $5 in 2023. This 37.65 lbs yield increase with row cover translates to an $188.25 increase of revenue. Our single plot area was 37.5 ft2 and thus our row cover plot area was 75 ft2. This trial has demonstrated a potential $109335.60 / acre increase in African eggplant revenue by using row cover. Farmers qualitatively reported horticultural benefits to row cover as well. On June 22, MAP farmer shared “there are so many more flowers on eggplants under row cover.” Project team members and MAP farmers noted darker green foliage on plants under row cover.

Lesson learned from this trial on best practices for using row cover include: regular weeding and drip irrigation are helpful for row cover success and using mulches can help; row cover may be most successful in areas where crops have not been previously grown for a few years or in areas that are known to be free of targeted pest.

MAP Farmer Katie reported the trial had numerous benefits for the farm’s social mission. She saw great value in the trial demonstration information sign (Figure 18) posted in front of the trial as a way to passively educators farm visitors exploring the farm. She shared hosting the trial was “fun and a great example for our community to see a field trial in action and be exposed to the process of agricultural research.” Katie estimates over 500 people interacted with the 2023 demonstration trial.

Education

On-farm Demonstration Trials: We anticipate a total of 15 farms across NYC and Buffalo will host demonstration trials that implement non-chemical pest management strategies such as host resistance, release of natural enemies/biological control, pest exclusion, intercropping or companion planting, to name a few. Farms will be recruited via the relationships that project members have already established with growers in NYC and Buffalo. The on-farm trials will provide growers the opportunity to observe the benefits of pest management practices first-hand.

Workshops: On-farm workshops will be held to facilitate peer to peer learning. We anticipate hosting or participating in 3 workshops per year (9 total over project period). Workshops will be predominantly held in NYC or Buffalo, with 2-3 workshops prioritized for another urban area, i.e. Syracuse, Rochester, Albany, Binghamton, etc. Workshops will be advertised on the Cornell Vegetable Program page, Harvest NY page, social media accounts, and in other relevant newsletters. The project team will adapt meetings to a virtual format if needed. Workshops will concentrate on topics like pest identification, scouting, cultural, mechanical, and biological controls, creating beneficial habitat for natural enemies, etc. Farms in Buffalo and NYC that host pest management trials will serve as locations for workshops. We estimate 10 farmers will attend each meeting. The project team will maintain a list of growers that attend workshops, and provide technical assistance to growers via email, phone call, or in-person visits, and/or through regular scouting. Results will be made available to organizers of winter educational events (virtual or otherwise) such as the NOFA-NY Winter Conference, the NYC Urban Agriculture Symposium, or the Urban Food Systems Symposium.

Rural Farm Tours: The project team will host a series of rural vegetable farm tours in order to expose urban growers to rural vegetable production, pest management on a larger scale in both organic and conventional settings, scouting, common equipment used to manage pests, and preferred management practices. Shared learning on common issues creates community building opportunities between urban and rural farmers, who may be separated not only by geography, but also cultural and racial differences.

A ‘Sustainable Pest Management Guide for NE Urban Agriculture’ will be created as part of this project. Cities, including Buffalo and NYC are home to a large proportion of immigrants and refugees. In Buffalo Public Schools more than 83 languages are spoken, such as Spanish, Arabic, Karen, and Somali. To reduce barriers to accessing this knowledge, our guide will be translated into three foreign languages to-be-determined by engaged farmers.

All growers that participate in workshops held during the duration of the project will receive a virtual or paper copy of the UA sustainable pest management manual once completed. The manual will be made available online as a pdf for download.

Farm Visits: The project team will conduct 100 visits with urban farmers across NYS per year over the course of the project, totaling 300 by the end of the project.

Milestones

1) Urban farmers in Buffalo and NYC agree to implement on-farm sustainable pest management trials such as crop rotation, pest exclusion, resistant varieties, release of beneficial insects, etc. Activity: Project team members utilize existing relationships with urban growers in Buffalo and NYC to recruit 15 sites suitable for on-farm pest management demonstration trials. Team members work with farmers to identify pest priorities and preferred management practices. We anticipate approximately 5 farms per project year to reach this milestone, and will report annually on this progress.

15

15

November 30, 2024

In Progress

In the first year of the project, progress toward this milestone included the recruitment of 3 farms in Buffalo and 2 in New York City to implement on-farm sustainable pest management trials including as crop rotation, pest exclusion and the release of beneficial insects. In Buffalo, Swede Midge and Striped Cucumber Beetle were identified by growers as priority pests. In New York City, Two Spotted Spider Mite and Cabbage Whitefly were major pests. Cabbage Whitefly in particular is of note as it is not a common pest in the Northeast, yet was the most prevalent pest on some NYC farms.

In the second year of the project, progress towards this milestone included the recruitment of two returning and four new farms in New York City and three returning and one new farm in Buffalo to implement on-farm sustainable pest management trials. In New York City, brassica pests including cabbage whitefly were identified as major pests, as well as pillbugs. Management tactics trialed this year included crop rotation, releasing biocontrols, and reducing soil pH. In Buffalo, aphids, Swede Midge and Cucumber Beetles were again identified by growers as priority pests. Management tactics trialed this year included releasing biocontrols, crop rotation, and using insect exclusion netting.

In the third year of the project, progress towards this milestone included the recruitment of four returning and one new farm in New York City, four returning and one new farm in Buffalo, and two new farms in Rochester to implement on-farm sustainable pest management trials. In New York City, cabbage whitefly, spotted lanternfly and cucurbit downy mildew were identified as major pests. Management tactics trialed this year included crop rotation, releasing biocontrols, physical barriers, and growing disease resistant varieties. In Buffalo, aphids, flea beetles and Swede Midge were identified by growers as priority pests. Management tactics trialed this year included releasing biocontrols, using crop covers, monitoring pest populations through trapping, and regular scouting. In Rochester, brassica pests such as Swede Midge were identified by growers as priority pests. Management tactics trialed this year included monitoring pest populations through trapping and regular scouting.

2) Urban farms across cities in NYS (Albany, Rochester, Buffalo, Troy, Binghamton, Syracuse, NYC, etc.) complete survey on the predominate pest issues, preferred pest management practices, perceived benefits, resources and information needed, etc. Activity: Project members craft survey and submit to 75 urban farms across NYS.

50

34

March 01, 2022

In Progress

A survey has been created in print and online form. It has been distributed on four relevant program websites, two newsletters, two list servs and over six social media accounts estimating to reach over 4100 people. Our target audience for the survey is urban growers (farmers and gardeners). We are defining “urban” growers using the USDA definition of urban - as people growing in areas located in/near urbanized areas (have a population of 50,000 or more) or in/near urban clusters (have a population between 2,500 and 50,000). Project team members have had success asking growers survey questions directly and recording responses. This has led to informative conversations helping to shape the direction of this project. At this time, 34 farmers have responded to the survey. In Fall 2023, we reached out to educators directly working with urban agriculture communities that project team members are not closely associated with including Batavia, Syracuse, Skaneateles, Utica and Binghamton for support in survey distribution.

Our original proposed completion date was 3/1/2022 and this was not met due to team personnel changes. We now aim to achieve this milestone by 4/1/24.

3) Urban farmers/managers/youth interns are exposed to rural vegetable production and pest management. They learn about the predominate pests in rural settings. Rural farmers learn from urban growers about their challenges in managing pests and provide advice on how pest controls could be adapted to urban settings. Activity: Urban farmers tour rural vegetable farms outside Western NY or NYC.

30

30

October 31, 2023

In Progress

Through collaboration with Mid-Hudson Collaborative Regional Alliance for Farmer Training (CRAFT), a group of 30 NYC urban farmers and students toured Choy Division Farm on Sept 29, 2022. The group learned from farmer, Christina Chan, an urban farmer who left the city to pursue her farm dream. Choy Division is a small vegetable farm located outside of NYC that is focused on growing East Asian heritage crops using regenerative agricultural techniques.

4) Service providers (CCE Educators, NRCS staff, other support agencies) gain knowledge on pest management practices that are effective on urban farms. Activity: service providers attend regional and statewide workshops, project staff meet with service providers one-on-one, service providers read online posts with project data, attend demonstration workshops at host farms.

15

20

15

108

November 30, 2024

In Progress

In 2022, one statewide in-person workshop (duration= 1.5 hour) was held on “Unique Pest Challenges in Urban Agriculture” at the CCE Agriculture, Food & Environmental Systems In-service conference. This conference is geared towards CCE educators, industry professionals and Cornell faculty to discuss latest developments in research and practice. Our workshop shared updates on this year’s top pests and management strategies on urban farms in New York City, Buffalo, and other cities across the state.

In 2023, two statewide in-person workshops (duration each= 1.5 hour) were held at the CCE Agriculture, Food & Environmental Systems In-service conference. Workshops shared updates on spotted lanternfly research and best practices for conservation biocontrol on urban farms. Additionally, a group of 20 service providers toured Massachusetts Avenue Project urban farm in Fall 2023 observing the flea beetle pest management demonstration trial and discussing pest management practices that are effective on urban farms (Figure 21).

5) NYS urban farm managers, adult employees, and youth learn about sustainable pest management. They will improve their identification skills of pests that are frequently problems on urban farms. They will learn how to scout for pests, understand the concept of thresholds, and gain confidence in their ability to accurately identify pests. Activity: Farmers attend regional and statewide workshops/conferences, participate in on-farm discussions, and attend on-farm workshops.

150

4

514

108

February 29, 2024

In Progress

Four different events were held in 2021, 3 virtual and 1 in-person. A total of 87 individuals were reached through these events. The curriculum for these events was largely focused on beneficial insects; how to attract, rear, create habitat for them. The pests of concern were aphids, Two Spotted Spider Mite and Cabbage Whitefly.

Nine different events were held in 2022, 4 virtual and 5 in-person reaching a total of 151 individuals. Workshops covered topics including scouting and pest identification, understanding life cycles of important pests and how to manage them, understanding beneficial insects, and using organic and biopesticides. Three workshops were targeted specifically towards youth, with a focus on insects on the farm, building healthy soils, and cultivating healthy land and community.

Thirteen events were held in 2023, 2 virtual and 11 in-person reaching a total of 276 participants. Workshops covered topics including scouting and pest identification, understanding life cycles of important pests and how to manage them, understanding beneficial insects, and using organic and biopesticides. Four workshops were targeted specifically towards youth, with a focus on IPM on urban farms, scouting and pest management.

To date, there have been 26 events for a total of 43.25 program hours and reaching 514 individuals.

|

Date |

Duration (H) |

Attendance |

Delivery |

Title |

|

3/26/2021 |

2 |

14 |

Virtual |

Intro to IPM for Urban Vegetable Growers |

|

3/30/2021 |

2 |

12 |

In-person |

Pest Management for Urban Farmers |

|

5/4/2021 |

1.5 |

44 |

Virtual |

Recognizing and attracting natural enemies to urban farms and gardens |

|

9/30/2021 |

1 |

17 |

Virtual |

Basic Insect Rearing for Urban Ag IPM |

|

1/24/2022 |

3 |

56 |

Virtual |

Urban Farmer-to-Farmer Summit |

|

3/3/2022 |

1.25 |

19 |

Virtual |

Urban Ag Pest Updates: Twospotted Spider Mite |

|

3/9/2022 |

1.25 |

17 |

Virtual |

Urban Ag Pest Updates: Cabbage Whitefly |

|

5/10/2022 |

1 |

12 |

Virtual |

Minimized Pest Control Risks on the Urban Farm |

|

7/28/2022 |

1 |

10 |

In-person |

Insects: Beneficials and Pests |

|

8/4/2022 |

1 |

10 |

In-person |

Composting and Healthy Soils |

|

8/11/2022 |

1 |

12 |

In-person |

Cultivating Healthy Land and Community |

|

8/18/2022 |

2.5 |

7 |

In-person |

Organic Pesticide Discussion and Demo |

|

11/18/2022 |

1.5 |

8 |

In-person |

Unique Pest Challenges in Urban Agriculture |

|

2/23/2023 |

1 |

36 |

Virtual |

Conserving friendly insects on urban farms and gardens |

|

3/7/2023 |

1.25 |

15 |

Virtual |

NYC Vegetable Pests & Diseases: 2023's Most Wanted |

|

6/9/2023 |

2 |

8 |

In-person |

South Lawn Farm Workforce Development Scouting Workshop |

|

7/8/2023 |

2 |

20 |

In-person |

Integrated Pest Management workshop |

|

7/26/2023 |

2 |

12 |

In-person |

IPM on the Urban Farm |

|

8/2/2023 |

2 |

12 |

In-person |

IPM on the Urban Farm |

|

8/3/2023 |

2 |

21 |

In-person |

Biological Besties - A Cornell IPM Skillshare Event |

|

8/9/2023 |

1 |

18 |

In-person |

Pest scouting workshop |

|

8/9/2023 |

2 |

12 |

In-person |

IPM on the Urban Farm |

|

10/3/2023 |

2 |

20 |

In-person |

Urban Ag Pest Management Needs Service Providers Tour |

|

10/12/2023 |

3 |

22 |

In-person |

Plant Health Care and Urban IPM |

|

11/7/2023 |

1.5 |

45 |

In-person |

Spotted Lanternfly Update |

|

11/8/2023 |

1.5 |

35 |

In-person |

Conservation Biocontrol |

6) 100 Sustainable recommendations from service providers (CCE Educators, NRCS staff, other support agencies) to farmers on disease resistant varieties, crop rotation, purchasing and releasing biological controls, insect/disease identification, and so on. Activity: Service providers meet with farmers, consult with project staff, provide follow up visits to farms to verify successful implementation, provide data to project staff.

25

20

33

October 31, 2023

In Progress

In 2023, we conducted an urban farm scouting program with seven farms in Buffalo and two farms in Rochester. A project team member visited each farm on a regular basis three to ten times throughout the growing season making note of crop health, pests and diseases observed. This information was shared with farmers as well as management recommendations. Some of these farms host summer youth and young adult employment programs. Occasionally, the young adults would participate in scouting. After participating in a scouting session, CCE Monroe South Lawn Farm Manager Mike shared “wow I am out here every day and have noticed more things in this last hour than my entire time on the farm. I understand now why it is important to monitor the crops.”

7) Northeast urban farm managers, adult employees, and youth will be exposed to sustainable pest management on urban farms and the corresponding economic and environmental benefits via on-line publications (VegEdge, Harvest NY newsletter), social media posts, email consultation, phone consultation, or on-farm visits.

500

20

514

108

February 29, 2024

In Progress

Progress towards this milestone includes 15 articles in the Cornell Vegetable Program newsletter “VegEdge” and 14 articles in the Harvest NY Urban Agriculture newsletter “NYC Market Growers Update.” There have been over 50 social media posts relating to sustainable pest management on urban farms shared on team social media. To date, there have been an estimated 218 farm visits and 150 off-farm consultations (phone and email) made by the project team. There have been 514 participants in total in workshops related to this project thus far.

Figure 22. Multiple translators at work in an Urban Pest Management workshop in Buffalo, NY.

Milestone Activities and Participation Summary

Educational activities:

Participation Summary:

Learning Outcomes

Urban Fruits and Veggies (UFV) is an urban farm on the East Side of Buffalo growing on ¼ acre in raised beds and one high tunnel. They focus on mixed vegetable and herb production with plans to expand to hydroponic vegetable and fruit production at their second site. Over the course of this project, UFV has trialed releasing biocontrols to manage aphids, and using insect exclusion netting to help decrease pest pressure in general and support biocontrol release efforts.

Through interviews and surveys, the UFV farm manager reported that these integrated pest management practices “fit in well with the mission of our farm. [On the farm], we try not to use chemicals and grow food with our community in mind.” The UFV president added “We serve underserved communities- traditionally there has been a lack of care when working with underserved communities. [When producing food], we always have the community in mind, we want to provide them with better quality, increased variety, and nutrient dense crops. This way of growing cost more and is more labor intensive, but we feel our community is worth it.” The UFV education programs include sustainable pest management content and the farm is planning to reach over 100 participants -a mix of youth and adults- in the next year.

The Brewster Street Farm with Journey's End Refugee Services offers the Green Shoots for New Americans Program which facilitates urban farming opportunities on Buffalo’s East Side. The farm grows numerous culturally important vegetables from farmer participants immigrating from Nepal, Afghanistan, Bhutan, and more. Over the course of this project, Brewster St has trial releasing biocontrols to manage aphids and Swede Midge.

Through interviews and surveys, the Brewster Street Farm manager reported that these pest management practices “fit in well with the farm and are a good lesson for our farmers.” Early in the growing season, the farm manager worked with farmer participants in the Green Shoots for New Americans Refugee Agricultural Program to identify aphids and remove them from plants by hand. In addition, they introduced concepts of beneficial insects. By the end of the season, the farm manager reported “Now if [farmer participants] see a ladybug, they move it to a plant with aphids.”

- Figure 23. Common Roots Urban Farm, host of our exclusion demonstration.

Performance Target Outcomes

Target #1

15

Urban farmers in Buffalo and NYC will implement sustainable pest management practices.

15 urban farm on at least 4 acres total.

Farms will see an increase in revenue of $2000/acre; and/or report quantifiable improved success in their social missions such as number of youths gaining pest management skills.

In progress