Final report for LS14-264

Project Information

A team led by the National Center for Appropriate Technology studied opportunities to create value-added food products from sustainably-grown fruits and vegetables, a market sector that appears ripe for growth in Texas. We took a "Farmer First" approach, focusing on the needs of growers and the goal of increasing their net incomes. We did extensive market research, educated producers, engaged rural civic and economic development leaders, and built linkages with food buyers and other food industry professionals. Our study confirmed that there are good opportunities for growers, especially for making products at small scale and selling them via direct marketing, taking advantage of Texas Cottage Food Law. We evaluated several promising value-added products and saw special opportunities to work with towns located within 50 miles of major cities, creating jobs through small-batch food manufacturing. Institutional and wholesale markets for processed foods are virtually untouched in Texas, and are a growing opportunity. We created a directory of resources, several cost-calculating tools, and a decision-making workbook for growers. We gave more than 20 presentations and workshops: raising awareness of opportunities, educating growers about food safety and other essential topics, and sharing our findings and tools with communities throughout the Southern SARE region. For more information about the Beyond Fresh project, contact Co-PDs Mike Morris (mikem@ncat.org), Robert Maggiani (robertm@ncat.org), or Sue Beckwith (sueb@texaslocalfood.org).

A team led by the National Center for Appropriate Technology studied opportunities to create value-added food products from sustainably-grown fruits and vegetables, a market sector that appears ripe for growth in Texas. We took a "Farmer First" approach, focusing on the needs of growers and the goal of increasing their net incomes. We did extensive market research, educated producers, engaged rural civic and economic development leaders, and built linkages with food buyers and other food industry professionals. Our study confirmed that there are good opportunities for growers, especially for making products at small scale and selling them via direct marketing, taking advantage of Texas Cottage Food Law. We evaluated several promising value-added products and saw special opportunities to work with towns located within 50 miles of major cities, creating jobs through small-batch food manufacturing. Institutional and wholesale markets for processed foods are virtually untouched in Texas, and are a growing opportunity. We created a directory of resources, several cost-calculating tools, and a decision-making workbook for growers. We gave more than 20 presentations and workshops: raising awareness of opportunities, educating growers about food safety and other essential topics, and sharing our findings and tools with communities throughout the Southern SARE region. For more information about the Beyond Fresh project, contact Co-PDs Mike Morris (mikem@ncat.org), Robert Maggiani (robertm@ncat.org), or Sue Beckwith (sueb@texaslocalfood.org).

Objective 1. Research opportunities for value-added processing of sustainably-grown fruits and vegetables in Texas, with special attention to the appropriate scale of production.

Objective 2. Increase the sales and profitability of value-added products by sustainable and organic fruit and vegetable growers in Texas.

Objective 3. Educate and organize growers, facilitating key decisions about topics such as appropriate business structures, values-based branding, sustainability requirements, and scale of production.

Objective 4. Cultivate increased collaboration, coordination, and support for value-added enterprise development in the sustainable and organic sector by strengthening inter-industry value chains and rural-urban linkages and quantifying regional economic impacts.

Introduction

In our conversations with small, mid-sized, and diversified farms in Texas over the past few years, many have reported declining net incomes. Some blamed competition from numerous food delivery and “meal-in-a-box” services. Others felt that farmers’ markets were proliferating faster than consumer demand. This statement from Gary Rowland of Hairston Creek Farm is typical: "We've been farming for over 20 years and now we have to sell at six markets a week to earn what we used to earn at two markets." Time after time, growers told us that they saw value-added enterprises as the best hope for increasing their net incomes. By “value-added” we mean (approximately) food that is prepared in some way that increases its economic value, instead of being sold fresh and whole. Hence our project name: Beyond Fresh.

It’s not hard to see why value-added products are appealing to growers. When all goes well, multiple factors work to the farmer’s advantage, enhancing profitability and consumer appeal. Value-added products typically have a long shelf life, and a zucchini or cucumber in a fermented relish can be worth more per pound than it would sell for in a fresh, whole state. Blemished fruits & vegetables can be worth dramatically more. Moreover, the cottage food laws in most states have opened up a range of new opportunities: prepared foods that can now be made legally in a home kitchen and sold directly to consumers.

We undertook this project at the direct request of growers. They wanted to know more about the issues and risks associated with value-added processing. They wanted to know the scale at which value-added processing would benefit them most. And for each value-added enterprise that looked promising, they had many specific questions about up-front capital investment, operating costs, and the requirements of manufacturing, marketing, storage, distribution, and branding. We set out to investigate the opportunities for selling value-added products that are both local and made from sustainably-grown (or organic) ingredients. Our primary focus was central Texas, which offers an ideal combination of strong markets and the greatest concentration of sustainable growers in the state.

The importance of value-added enterprises to rural economic development is widely acknowledged. In fact, a major objective of Southern SARE is to “strengthen rural communities by creating economic conditions, including value-added products, that foster locally-owned business and employment opportunities.” We had many questions about rural economic development in Texas, and included an economist on our team with a special interest in rural development.

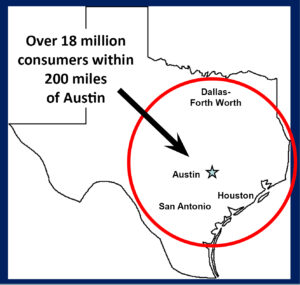

At least in theory, value-added products offer higher profit margins and sales opportunities during the off-season. They can mitigate risk factors such as fluctuating production levels and open possibilities for growers to move beyond direct sales and into wholesale marketing. And the potential market for these products is tremendous. Within 200 miles of central Texas there are at least 18 million people, including the cities of Austin, Houston, Dallas, and San Antonio. The marketing pathways from farms to these enormous populations of consumers appear to be extremely under-developed.

Sources

Brown, Cheryl, and Stacy Miller. 2008. “The Impacts of Local Markets: A Review of Research on Farmers Markets and Community Supported Agriculture (CSA).” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 90(5): 1298-1302.

Dandrew, Bob, 2013. Hudson Valley Food Hubs Initiative: Research Findings and Recommendations. Local Economies Project, The New World Foundation.

Swenson, D. 2008. Estimating the production and market-value based impacts of nutritional goals in NE Iowa. Ames, IA: Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture.

Cooperators

- (Educator)

- - Producer (Educator)

- (Researcher)

- (Educator)

- (Researcher)

- (Educator)

- (Researcher)

- (Researcher)

- - Producer (Educator)

- (Educator)

- (Educator)

- (Researcher)

Research

In our work with farmers we have often noticed a disconnect between the urgent and practical needs of growers and the slow and deliberate pace of academic research. Texas growers trying to survive in rapidly-changing food markets told us that they needed answers and they needed them fast. We used diverse methods, including interviews and case studies. While we had outstanding academic researchers from two different universities on our team, our focus was not on resolving scientific controversies or reaching definitive scientific conclusions but rather on "applied" or "pragmatic" research that would generate useful guidance and problem-solving tools. We make no apology for this approach, and strongly believe it was the best way to bring about positive impacts.

In our work with farmers we have often noticed a disconnect between the urgent and practical needs of growers and the slow and deliberate pace of academic research. Texas growers trying to survive in rapidly-changing food markets told us that they needed answers and they needed them fast. We used diverse methods, including interviews and case studies. While we had outstanding academic researchers from two different universities on our team, our focus was not on resolving scientific controversies or reaching definitive scientific conclusions but rather on "applied" or "pragmatic" research that would generate useful guidance and problem-solving tools. We make no apology for this approach, and strongly believe it was the best way to bring about positive impacts.

Our goal from the outset was to put a high-caliber market research and product development team to work for the small- and mid-sized sustainable and organic farms of Texas. We wanted to "level the playing field," delivering a level of professional service that has generally only been available to the state's large agribusinesses. For example, we were extremely fortunate to have Dr. Rodney Holcomb on our team, one of the leading experts on value-added food products in the United States. As an academic researcher at a major university, Dr. Holcomb had access to proprietary market research done by trade associations and other organizations. These studies cost thousands of dollars apiece and are rarely seen by growers, local food advocates, or the general public because of their high cost.

It's also worth noting that Beyond Fresh was led by a non-profit organization, something that is quite unusual for a Research and Education project in the Southern SARE Region. In the six years before our project was funded (2008-2013) only 5 of 56 Southern SARE R&E grants had been awarded to non-profits. By contrast, 42 of these grants went to Land Grant universities. Our team was intentionally large and diverse, including 16 paid partners, half of whom were farmers.

Objective 1. Research opportunities for value-added processing of sustainably-grown fruits and vegetables in Texas, with special attention to the appropriate scale of production.

- We conducted a survey of growers, to identify those interested in processing their crops as value-added products (or already doing this kind of processing). Interest in value-added products was extraordinarily high. Out of 78 responses, 42% were already doing value-added processing and 56% said they were interested. In other words, 98% of respondents were either already doing value-added processing or interested in it.

- We did extensive literature research on topics such as branding, market positioning, scale, packaging, labeling, and product development strategies, including a close study of previous SARE-funded research on related topics.

- We interviewed nine farmers on their preferred crops and value-added products.

- We had conversations with dozens of other growers, including several who had already built commercial kitchens or launched value-added enterprises.

- We met in person or by phone with eight retail and wholesale food buyers, to understand existing production capacity, needs, and gaps. We asked many specific questions: For example, would they buy ready-to-eat, ready-to-cook, frozen, dehydrated, or fermented items, or vegetables pre-chopped to use as ingredients? At what volume? At what price?

- We met with grocers, restaurants, company cafeterias, schools, universities, co-packers, and others to understand their requirements, demand, and budget for locally processed foods from locally grown crops.

- We interviewed food processors, rural community economic development leaders, commercial kitchen owners, regulators, and potential enterprise funders.

- We interviewed experts in the field of entrepreneur development and business incubation to understand how choice of business model, business goals, capitalization, growth patterns, founder qualifications, and other factors affect the scale of value-added processing.

- We interviewed experts in natural and organic manufacturing and retailing to understand the likely marketing methods and branding strategies that they would use. We sent members of our team to various trade shows and meetings, including the large Natural Products Expo East in Baltimore, Maryland.

- We created a survey of the demand for value-added fruits and vegetables as ingredients in existing products, sent it to over 600 food entrepreneurs, and received 86 responses.

- We conducted a survey of farmers market managers, to learn their requirements and restrictions for value-added products, such as whether they would allow ingredients not grown by a member of the market.

Objective 2. Increase the sales and profitability of value-added products by sustainable and organic fruit and vegetable growers in Texas.

Based on the interviews, surveys, and market research, our Grower Lead Team identified 11 value-added products for careful study. These were fermented sauerkraut; salsas; pickled vegetables; dehydrated vegetable snacks; dehydrated vegetable soup mix; freeze-dried vegetables; relishes; ready-to-eat meals; vacuum-fried vegetables; freeze dried fruit; and fruit jams and jellies.

Dr. Holcomb and his colleague Dr. Timothy Bowser conducted a study of these 11 food categories, giving recommendations for equipment, production methods, labeling, and packaging, considering process constraints, shelf life, and other critical success factors. They also researched market trends, barriers, and opportunities for value-added product development in Texas. Their in-depth report covered topics such as Organic Foods, Reaching Millennial Shoppers, and the Rise of “Free-From” and Biodynamic Foods.

We created several tools that will help growers develop value-added products and increase their sales and profitability:

- A Resource Directory: a clickable map that includes commercial kitchens; food processors, brokers, and distributors; food analysis labs; sources of equipment, packaging, labels, funding, and technical assistance; and state and local agencies involved in local food development.

- A series of four Product Cost Calculators, aimed at calculating the rate of return at four different scales of production. We created separate calculators for on-farm, hourly rental, and long-term lease of a commercial kitchen. And we created a fourth calculator for building a completely new commercial kitchen.

- A decision-making workbook--Beyond Fresh: a Food Processing Guide for Texas Farmers--helping growers decide what products to create, how to make and sell them, and at what scale.

Objective 3. Educate and organize growers, facilitating key decisions about topics such as appropriate business structures, values-based branding, sustainability requirements, and scale of production.

We did extensive education for growers. A detailed list of activities is included in the Education section of this report. A few highlights:

- The Texas Organic Farmers and Gardeners' Association (TOFGA) added numerous workshops on value-added products to its annual conferences in 2017 and 2018, greatly increasing education to its members about value-added enterprise opportunities.

- Our paid Grower Lead Team was actively involved in every aspect of the project, and held work sessions throughout the project.

- We offered 20 presentations or workshops, attended by 445 unique persons.

- We included a lawyer on our team (Judith McGeary) who is an expert on food-related laws and regulations, and featured her (along with other presenters) at well-attended trainings on Federal Food Safety Rules for Farmers and the Texas Cottage Food Law.

- We offered an innovative Media Training for Farmers, that included role-playing and videotaped mock interviews with reporters.

- We held 226 one-on-one consultations with growers, providing technical assistance related to local food and value-added enterprises.

- We greatly improved and expanded the Value-Added Food Products area of NCAT's ATTRA website, and posted project training materials and educational products to this webpage.

- We created many other web and print resources, which are listed in the "Curricula, factsheets, educational tools" section of this report, below.

Objective 4. Cultivate increased collaboration, coordination, and support for value-added enterprise development in the sustainable and organic sector by strengthening inter-industry value chains and rural-urban linkages and quantifying regional economic impacts.

We arranged and facilitated meetings between state and federal agencies, grower organizations, university researchers, and sustainable agriculture non-profits. We develop solid working relationships with representatives from economic development agencies, private funders, and organizations that can support the development of value-added products, such as USDA Rural Development, Slow Money, Austin Foodshed Investors, Capitol Area Council of Governments, Elgin Economic Development Corporation, Elgin Chamber of Commerce, Austin Economic Development Corporation. Texas Department of Agriculture, and Accion Texas. We hosted a gathering of policy makers and economic development directors from within 40 miles of Austin to explore interurban linkages and economic impacts of our regional food system. Austin consumers have taken a keen interest in the importance of local food to economic development. A 2013 report concluded that “The food sector in Austin touches every element of the community...Food has an economic impact commensurate with many other core aspects of the local economy” (TXP Inc., 2013).

Austin to explore interurban linkages and economic impacts of our regional food system. Austin consumers have taken a keen interest in the importance of local food to economic development. A 2013 report concluded that “The food sector in Austin touches every element of the community...Food has an economic impact commensurate with many other core aspects of the local economy” (TXP Inc., 2013).

Dr. Rebekka Dudensing of Texas A&M University was a key member of our project team. She did an economic impact analysis of local, sustainably-produced, and value-added products on rural economic development in central Texas (Dudensing, 2018), presented her findings at a number of workshops and events, and created educational handouts on the economic impact of value-added food products.

The City of Elgin was also an important partner in our project. The City's continuing interest in economic development through sustainable agriculture was a major resource and asset. Elgin is one of five cities in Central Texas chosen to participate in the Sustainable Places Project of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). The City's goals include “developing food infrastructure that can support the viability of local agriculture, and establish downtown as a food hub.”

Sources

TXP, Inc. 2013. “The Economic Impact of Austin's Food Sector.” Study commissioned by the City of Austin and available from the City of Austin's website, www.austintexas.gov.

Dudensing, Rebekka, 2018. "Economic Impact through Value Chains."

Taking a Farmer-First Approach

Books and articles about value-added food enterprises almost always start from the question “What does the market want?” Do consumers want kale chips, fruit roll-ups, fermented carrot slices, or freeze-dried strawberries? This approach is primarily demand-driven, and we’ll refer to it as the Market-First Approach. It is certainly the prevailing point of view in the food processing industry.

Do consumers want kale chips, fruit roll-ups, fermented carrot slices, or freeze-dried strawberries? This approach is primarily demand-driven, and we’ll refer to it as the Market-First Approach. It is certainly the prevailing point of view in the food processing industry.

We took a different approach.

For most small and mid-scale farmers, product development doesn't start with "What does the market want?" It starts with "What crops do I have?" and "What can I make with them?" Then (finally) “Of the products I can make, and enjoy making, which ones do consumers want?”

Taking a Farmer-First approach makes a big difference in how you look at product development. Exploring the implications of this approach was a major focus of our project. And we developed this simple-yet-powerful idea in great detail in our decision-making workbook.

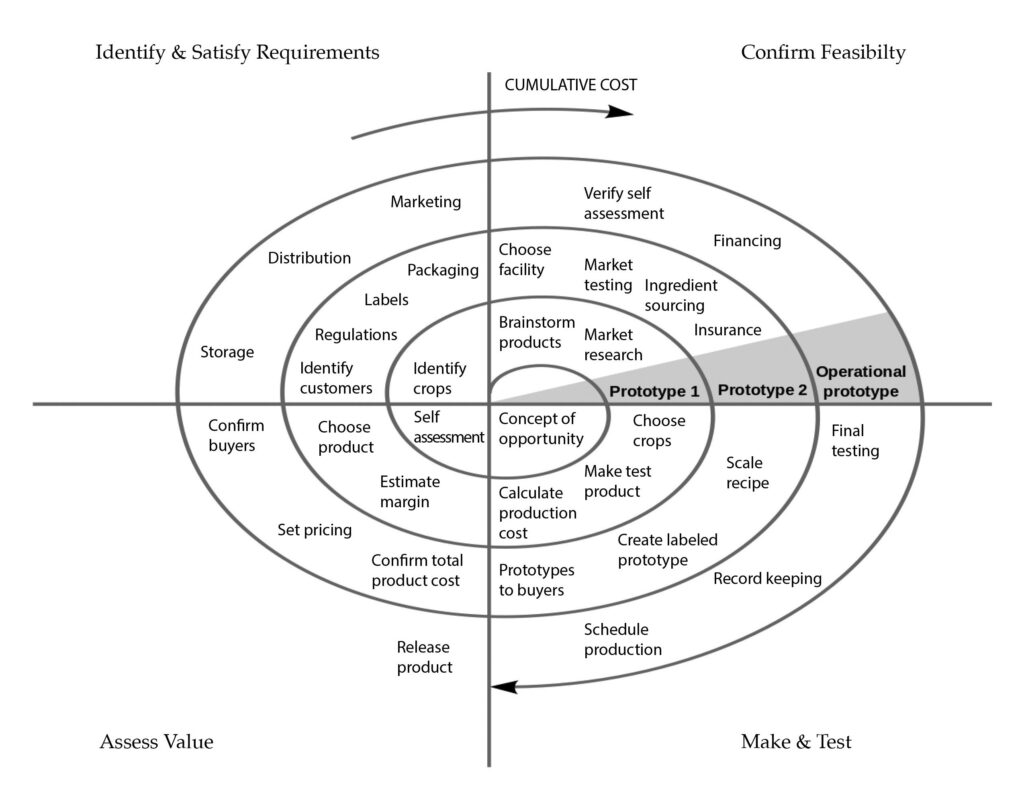

For small to mid-sized farmers, food product development ordinarily begins by thinking about crop production and proceeds through a series of test batches or prototypes, with frequent evaluations and reality-checking along the way. Trial and error play a large role, and failure is a normal and expected part of the process. Aside from profitability, we found that regulations are the most important factor determining the feasibility of value-added products. But other reasons for failure are harder to anticipate and could relate to recipes, labels, production requirements, or a host of other factors. You won't know until you try. When a product fails, you go back, change something, and try again. It often take many attempts and iterations before everything works and the pieces fit together.

One of the accomplishments of this project was identifying and describing a model of value-added food product development that fits the way farmers think. This process is essentially iterative, and we came back to this model time and again in developing our workbook and training materials. The basic idea is captured in the diagram below:

Winners and losers

Our market research reached a broadly optimistic conclusion about the potential for making and selling value-added food products from local and sustainably-grown ingredients. Among other findings, we learned that interest in food provenance continues to increase, especially among younger consumers. At the same time there are growing expectations for convenience. These trends, among many others, point towards growing demand for processed and conveniently-packaged foods made from local ingredients.

We looked closely at fermented sauerkraut; salsas; pickled vegetables; dehydrated vegetable snacks; dehydrated vegetable soup mix; freeze-dried vegetables; relishes; ready-to-eat meals; vacuum-fried vegetables; freeze dried fruit; and fruit jams and jellies. Dozens of other product ideas emerged from our brainstorming sessions, including fruit ketchup; fruit paste; frozen shredded zucchini; frozen zucchini fritters; chocolate zucchini muffins; dehydrated squash chips, kale chips, or tomatoes; smoked tomatoes, peppers, or salsa; frozen ratatouille soup; kimchi; hot pickled okra; jarred tomatoes or peppers; green garlic paste; flax seed; dried greens (from brocolli leaves, chard, kale, collards, etc.) as powders for smoothies or ingredients sold to food makers; and products made from brassica leaves or moringa. Some fruits and vegetables that appear to have particularly good potential for value-added products in Texas are tree fruits (such as peaches, pears, and figs), cantaloupes or specialty melons, sweet potatoes, and butternut squash.

When we studied production requirements and economics, we found that only a small percentage of these products were likely to be profitable for farmers under "real world conditions." In the food world, scale is everything. A product that’s profitable in large-volume sales at the grocery store may be a risky logistical nightmare to make in small batches on a farm or in a commercial kitchen. We saw the best opportunities in products that can be made on-farm, under the Texas Cottage Food Law.

In our education and training materials, we urged growers to "start small and fail early." Every product idea is to some extent unique and needs to be considered on its own merits. To facilitate this evaluation process, we created four user-friendly Product Cost Calculators that can be used to look at profitability under varying assumptions.

We concluded that for most direct-market growers, it's not worth the trouble, cost, and risk to leave the farm and use a commercial kitchen. Those who choose to scale up to large volumes or sell their products wholesale will need to develop new skills and may need to completely change field management practices. Trying to get value-added products onto grocery store shelves (consumer packaged goods) is not a realistic goal for most small farms. For example, highly consistent supply and quality are essential to grocery stores. And seasonality -- normal in the produce department -- is absolutely not accepted or desirable on grocery store shelves.

While only a small percentage of value-added products generate high profit margins, taking a Farmer-First approach broadened our understanding of success. Value-added food enterprises can be worth considering for a variety of reasons. In some cases, a small profit margin is all the producer needs or wants, and many other considerations can be important. For example, food processing can be a good venture for aging farmers who want or need a lighter work load.

Negative consumer perceptions

The local food movement succeeded partly by convincing consumers of the premium value of fresh, whole fruits and vegetables. At the same time, consumers were developing negative associations with non-fresh produce. In their market research report, Dr. Holcomb and Dr. Bowser found that the tremendous recent growth in fresh vegetable sales has come largely at the expense vegetables that are canned, dehydrated, freeze-dried, and otherwise processed. Many consumers now think these products are too processed or have inferior taste compared to their fresh counterparts.

Among consumers, there are currently especially strong negative perceptions about canned and jarred fruits and vegetables, which have declined considerably in the marketplace. Frozen fruits and vegetables have been less affected. And dried and fermented foods appear to have the greatest market potential among processed foods, as sales have increased in recent years.

Consumers who prize freshness and are wary about processed foods need to be reassured with marketing messages that highlight positive features such as nutrition, local production, shelf life, and convenience. Successful marketing will appeal to nutrition, health, and convenience, and labeling must tell the whole "story behind the food." In their report, Dr. Holcomb and Dr. Bowser noted that Millennials are a key audience, and made specific marketing recommendations for three groups of Millennial food shoppers: Food Skeptics, Health-Conscious Independents, and Brand Loyal Eaters.

Consumer confusion

One of our research goals was to find out if creating value-added products from ingredients that were both local and sustainably-grown might support much higher prices and profit levels for growers. We learned that the answer is "probably not."

One of our research goals was to find out if creating value-added products from ingredients that were both local and sustainably-grown might support much higher prices and profit levels for growers. We learned that the answer is "probably not."

For one thing, many studies have shown that consumers don’t know exactly what labels like "local," "sustainable," and "organic" mean. This is not entirely the fault of consumers. For example, the overwhelming majority of packaged products in the grocery store labeled as "local" contain few if any locally-grown ingredients. The term "local" has no legal definition and most often means made in Texas or made by a Texan-owned company. The ingredients can, and usually do, come from far-away places.

There are also price ceilings that operate in the marketplace. Consumers will only pay so much more for (say) a 16-ounce jar of sauerkraut or a three-ounce package of sun-dried tomatoes. And consumer preferences are not necessarily rational. One study found that consumers who were willing to pay an average of $5.34 for blackberry jam made from local ingredients were only willing to pay $5.25 if the jam was labeled as BOTH organic and local (Meas et al, 2015).

An important finding of our project was that putting a fresh food item into a package separates consumers psychologically from the product. These psychological effects are complicated and hard to predict. But without the benefit of face-to-face interaction (as in direct-to-consumer sales at a farmers market), it's hard to get consumers to understand what's in the jar, let alone appreciate subtleties about where the ingredients came from or how they were grown. Consumer communication and education are big challenges for anyone attempting to capture the full value of products made from local and sustainably-grown ingredients.

Economic development potential

Our project included a strong economic development component, and confirmed that value-added food products made from locally-grown ingredients have real economic development potential in Texas.

Team member Dr. Rebekka Dudensing did economic impact calculations for products grown and processed in central Texas, using IMPLAN regional economic impact analysis software. Her study concluded that selling $1,000 worth of fresh tomatoes would generate $1,279 in total economic impact -- factoring in direct, indirect, and induced effects as money circulates through the local economy. By contrast, putting the same tomatoes into a canned sauce or salsa would generate a much larger total effect of $9,117 -- over seven times as much. Most of that increase is due to the increased value of the final product relative to the value of the unprocessed vegetables, and the processing stimulates additional activity across the economy as well. Benefits rippling through the local economy would include numerous non-agricultural industries.

While the economic development benefits of value-added food products are well-known, learning the actual dollar value of these effects in a real-world Texas example was a powerful and useful result from our project. We created handouts featuring these numbers, aimed at decision-makers. Many small-town mayors, city council members, and county commissioners, and other elected officials attended our workshops and networking events. These rural civic leaders were keenly interested in working with local farmers to develop value-added food products.

Every large city in Texas is surrounded by peri-urban areas and small towns, often bedroom communities with many residents who commute into the city to work at low-paying jobs. These towns are hungry to create jobs, and they understand manufacturing. The Beyond Fresh project confirmed the importance of connecting Texas farmers, food entrepreneurs, food buyers, and economic development professionals. And a significant accomplishment of this project was getting decision makers in many small Texas towns thinking seriously about food manufacturing as a job creation opportunity.

Untouched markets

Wholesale market opportunities are just beginning to develop in central Texas, and more work is needed to build them. Making the transition from direct-marketing to wholesale is a big and complicated step for farms.

Our research found good opportunities to sell ingredients to small-batch food manufacturers, where co-branding may be a possibility. Institutional markets for processed foods also seem to be virtually untouched in Texas and are a growing opportunity. For example, the City of Austin has launched a new Good Food Purchasing Program (GFPP) that prioritizes food from local farms. In May 2016 Austin Independent School District and the University of Texas at Austin became the first two organizations to pilot the GFPP program in Texas. Both are already buying fresh produce from Texas farmers. While not yet buying processed produce, they are interested in minimally-processed products such as carrot sticks, broccoli sticks, broccoli florets, and butternut squash cubes. The Beyond Fresh project led to a price study that has informed the work of the GFPP team in Austin.

Sources

Meas, T., W. Hu, M. Batte, T. Woods and S. Ernst (2015) “Substitutes or Complements? Consumer Preferences for Local and Organic Food Attributes.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 97(4): 1044-1071.

TXP, Inc. 2013. “The Economic Impact of Austin's Food Sector.” Study commissioned by the City of Austin and available from the City of Austin's website, www.austintexas.gov.

Education

-

- We created and distributed a workbook for growers: Beyond Fresh: a Guide to Food Processing for Texas Farmers. The book contains worksheets and exercises that producers can use to explore budgets and feasibility of value-added processing opportunities, tips on business planning and marketing, and information on packaging, labeling, regulations, grant and loan programs, and other topics.

- We created an online resource center on the ATTRA website that includes many materials and tools created through this project, to support farmer-driven value-added enterprises.

- We presented our findings at 20 meetings or workshops attended by 445 unique persons, of whom 310 were growers.

- The Texas Organic Farmers and Gardeners' Association (TOFGA) added workshops on value-added products to its annual conference. TOFGA is the leading statewide grassroots organization representing sustainable and organic producers in the state of Texas.

- We created a web-based directory of potential buyers and existing resources, including commercial kitchens, food manufacturing facilities, food brokers, food distributors and food analysis labs.

- The New Farm Institute training offered a full-day Media Training for Farmers: to hone farmers' presentation skills, help them develop key messages and "tell the story behind their food," improve their ability to work with public media (TV, radio reporters, bloggers), and apply these skills to interview situations.

- We hosted a gathering of policy makers and economic development directors from within 40 miles of Austin to explore inter-urban linkages and economic impacts of our regional food system.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation summary:

Curricula, factsheets, educational tools

In addition to the items listed below, many other products from the Beyond Fresh project are available from the Value-Added Food Products page of the ATTRA website.

- Beyond Fresh: a Food Processing Guide for Texas Farmers, by Mike Morris & Sue Beckwith. Chapters iinclude "Overview of the Farmer Decision Process," "Self-Assessment: Is Value-Added Right for Me?," "Product Recipes, Development, and Production," "Market Trends," "Can I Make Money?," "Regulations," "Labels & Packaging," "Funding," "Selling," "Distribution & Storage," and "Running Your Business."

- "Beyond Fresh Marketing Opportunities" (April 22, 2016), by Dr. Rodney B. Holcomb & Dr. Timothy J. Bowser, FoodMech, LLC. This market research report offers a great deal of practical advice and identifies appropriate equipment, methods, labeling, packaging, and processing scale for 11 promising value-added products that could be made in central Texas: fermented sauerkraut, salsas, and ketchup; dehydrated vegetable snacks and vegetable soup mix; freeze dried vegetables, relishes, ready-to-eat meals, vacuum-fried vegetables, fruit jams and jellies, and freeze-dried fruit.

- Four Cost Calculators allowing farmers and other food entrepreneurs to simulate financial performance and estimate gross margin for commercial kitchens operated under various ownership, scale, and product scenarios: Commercial Kitchen on Your Farm, Commercial Kitchen Hourly Rental, Commercial Kitchen Long-Term Lease, and Commercial Kitchen Build-Operate.

- Media Tips for Farmers, by the New Farm Institute.

- A brief report, Value-added Processing Options by Sue Beckwith, outlining various combinations of processing facility, sales outlets, brand ownership, product ownership, and distribution.

- A handout, Economic-Impact-through-Value-Chains, by Dr. Rebekka Dudensing, showing the economic impact of value-added products made from locally-produced ingredients.

Published press articles, newsletters

- Robyn Ross, "A Fork in the Road: Can the local food movement help Elgin reclaim its farming roots?" Texas Observer, February 21, 2017, pp. 40-44. Features project partners Sue Beckwith and Alex Bernhardt.

- March 30, 2016: Story in the Elgin Courier about our food safety workshop.

- Team member Rebekka Dudensing co-authored an article, "What Do We Mean by Value-added Agriculture?", that appeared in Choices: a publication of the Agricultural and Applied Economics Association. (Lu, R., and R. Dudensing. 2015. "What Do We Mean by Value-added Agriculture?" Choices. Quarter 4.)

Tours

- May 15, 2016: Farm tour showcasing the value-added food enterprises at Bernhardt's Farm. The tour was organized by the City of Elgin and was attended by 20 local residents, including economic development officials and other opinion leaders. A flyer is attached and a slideshow is here: https://vimeo.com/167131683.

Webinars, Talks, Presentations

- April 16, 2015: "Local Food Training" (Robert Maggiani), College Station, Texas (40 participants).

- January 6, 2016: "Food Safety Planning Session" (Judith McGeary, J.D.), a focus group meeting to identify what farmers need to know about these new rules (6 participants).

- January 13, 2016: "Value-Added Production" (Sue Beckwith & Robert Maggiani). Annual conference of the Texas Organic Farmers & Gardeners Association (TOFGA), Rockwall, Texas (35 attendees). (presentation and workshop evaluations are attached.)

- March 22, 2016: "Federal Food Safety Rules for Farmers" (Judith McGeary, J.D.), Elgin, Texas (31 participants). (workshop agenda and evaluations attached.)

- April 22, 2016: "Whole Foods Market Southwest Region Produce Supplier Meeting" (Robert Maggiani), Austin, Texas (20 participants).

- April 27, 2016: "Community Economic Development Impact of Local Foods" (Rebekka Dudensing), Elgin, Texas (32 participants).

- May 19, 2016: "Tasty New Thing: Practical Perspective for New Food Companies" (Chris Johnson, Stellar Gourmet), Elgin, Texas (32 participants).

- May 19, 2016: "Cottage Food Seminar" (Judith McGeary, J.D.), Elgin, Texas (32 participants).

- July 21-22, 2016: "Beyond Fresh in Central Texas" (Sue Beckwith). The National Value-added Agriculture Conference, Madison, Wisconsin. (Attached.)

- September 25-7, 2016: "Profit Plus Integrity" (Sue Beckwith). Annual conference of the Farm & Ranch Freedom Alliance, Bastrop, Texas (150 participants).

- February 13, 2017: "Beyond Fresh: Farmer Decision-Making for Value-Added Production" (Sue Beckwith & Robert Maggiani). Annual TOFGA conference, Mesquite, Texas. (40 participants. Evaluation attached.)

- February 13, 2017: "Media Training for Farmers" (Erin Flynn). Annual TOFGA conference, Mesquite, Texas. (30 participants. Evaluation attached.)

- February 13, 2017: "Resources for Local Food Development" (Sue Beckwith). Annual TOFGA conference, Mesquite, Texas. (Evaluation attached.)

- February 14, 2017: "The Food Safety Modernization Act and Cottage Foods" (Judith McGeary, J.D.), Mesquite, Texas. (24 participants. Evaluation attached.)

- February 14, 2017: "Food Safety Regulations: What farmers and artisan producers need to know right now" (Judith McGeary, J.D.), Mesquite, Texas. (25 participants. Evaluation attached.)

- February 14, 2017: "Value- Added: the Earth Elements Farm Story" (April Harrington). Annual TOFGA conference, Mesquite, Texas. (25 participants. Evaluation attached.)

- August 15, 2017: "Local Food Systems as Engines of Economic Development" (Robert Maggiani), San Marcos, Texas (50 participants).

- September 14, 2017: "Starting a Value-Added Food Business" (Sue Beckwith), Texas Hispanic Farmer & Rancher Conference, Mcallen, Texas (25 participants).

- February 2, 2018: "Value-Added Processing for Farmers" (Sue Beckwith, Jonathan Hogan), Georgetown, Texas (40 participants)

- February 2, 2018: "Food Systems from the Farmer View" (Sue Beckwith, Ava Cameron, Rebekka Dudensing), Georgetown, Texas (30 participants)

Workshop / field days

- November 15, 2016: "Media Training for Farmers" (New Farm Institute) for six farmers who were already exploring value-added food enterprises: introducing media concepts and including taped mock interviews, Austin, Texas.

- April 27, 2017: "Local Food as an Economic Development Driver" workshop attended by 30 economic development leaders from the 6 counties east of Austin. Agenda and evaluation are attached.

Learning Outcomes

Increased awareness of opportunities to develop value-added food products.

Improved ability to evaluate, plan, and secure funding for value-added food enterprises.

Improved ability to create value-added food products, including key topics such as product development, recipes, labeling, and packaging.

Increased understanding of laws and regulations governing food processing, including food safety rules and the Texas Cottage Food Law.

Improved marketing and media skills, including ability to work with reporters.

Project Outcomes

This project benefited family farmers and rural economies in Texas by answering fundamental questions about the market for value-added goods that are made from sustainably-grown fruits and vegetables. We stimulated the growth of this market and improved access to it by farmers. We built many linkages between diverse stakeholders, including entrepreneurs, elected officials, and local economic development leaders who are now looking at value-added foods more as a driver of economic development. Over time, we fully expect these relationships to result in many new value-added enterprises being launched in central Texas--directly benefiting farmers and rural communities.

We are sharing and widely distributing research results, tools, and templates from this project, allowing producers and communities throughout the Southern SARE region to derive similar benefits.

Our project enhanced the viability of sustainable agriculture in the South in several ways: We created specific new economic opportunities for sustainable and organic growers in Texas. We are already seeing increased engagement by rural economic development leaders. We expect to see widespread use of the tools we developed, by farmers throughout the Southern SARE region. Our project strongly engaged agencies at all levels, and represents the first major collaboration between the National Center for Appropriate Technology, Texas A&M, Oklahoma State University, and the Texas Organic Farmers and Gardeners' Association, building new capacity that will advance sustainable agriculture in Texas.

This project also increased the capacity of agricultural service providers in Texas to answer questions about value-added products: including those working for ATTRA, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension, and the Texas Center for Local Food.

Related Outcomes (Accomplishments that leverage SARE's investment, were inspired or partly caused by this project, but required no expenditure of SARE funds)

- A new Texas Center for Local Food (TCLF) was created in March 2016, a project of the Growers’ Alliance of Central Texas. The creation of an organization wholly devoted to local food is a major step forward for Texas. The TCLF website will become the home of our resource directory and other tools, and will continue supporting value-added food enterprises long after the end of our project. Many members of our project team were involved in this organization's creation, and Beyond Fresh Co-PD Sue Beckwith is Executive Director. For more information, contact Sue Beckwith, sueb@TexasLocalFood.org.

- In April 2018, the Elgin Economic Development Corporation approved $800,000 toward construction of a new Elgin Local Food Center (ELF).

- The Common Market has opened a new statewide food hub in Houston. Previously operating mainly in the mid-Atlantic and Georgia, the Common Market is a nonprofit regional food distributor with a mission to "connect communities with good food from sustainable family farms." Members of our project team held several meetings with Common Market staff while they were researching a potential expansion into Texas, and we are glad to welcome them to the state. They have the capacity to create linkages and greatly expand markets for local food in Texas.

- NCAT and the Texas Center for Local Foods joined forces with the Austin-based Sustainable Food Center on a successful proposal to USDA’s Local Food Promotion Program, to create a feasibility study for a central Texas food hub. Other partners include the City of Austin and FarmShare Austin.

- NCAT released a Feasibility Study for a Texas Organic Food Hub and Food Hub Planning Workbook in June 2015, co-authored by Robert Maggiani and Mike Morris.