Final report for LS22-375

Project Information

The economic opportunity represented by organic cotton premiums has captured the interest and commitment of many producers across the South. Semi-arid West Texas is conducive to successful organic cotton production. However, mechanical- and hand-weed control are neither environmentally nor economically sustainable options. Sheep integration in organic cotton systems has potential to suppress weeds and add value to the overall production system. Due to limited water, portions of irrigated land are often rotated with grain or forage crops with different timing of water demands. A new system, integrating sheep, cotton, annual forages, and perennial forages offers unique potential for diversification and ecological resilience.

A participatory research framework was employed to engage stakeholders with the research process and gain understanding of factors influencing producer management decisions relative to new or alternative practices. Field research trials were coordinated on the integration of sheep as natural weed control option in cotton systems and best-suited perennial and annual forages for a livestock integrated cropping system. Economic assessments were performed to identify changes in revenue vs. expenses, estimating ultimate changes in profitability relative to varying system components.

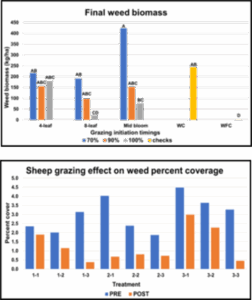

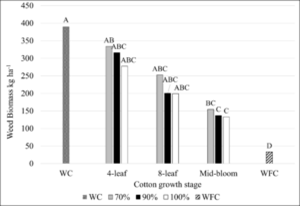

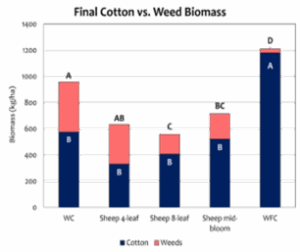

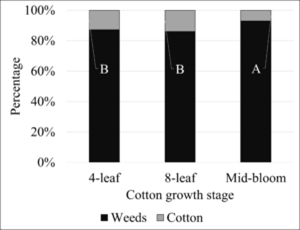

Trials assessing the effect of sheep grazing intensity and timing (cotton growth stage) indicated that sheep spent 87%, 86%, and 93% of feeding time grazing weeds rather than cotton with grazing initiated at the 4-leaf, 8-leaf, and mid-bloom stages, respectively. This supported the hypothesis that palatability of cotton declines with increasing maturity. Final cotton biomass was not influenced by year, intensity, or timing of sheep grazing treatments, but was greater when cotton was maintained weed-free without sheep. Final weed biomass was affected by year (P > 0.069) and timing of grazing (P > 0.036). Notably, grazing initiated at the 4-leaf stage resulted in greater weed biomass at the end of the growing season than grazing initiated at the 8-leaf stage. The key implication is that grazing too early imposed too much damage on the cotton, limiting the duration of the grazing event and lowering overall potential for weed removal.

Additional research assessed the effects of previous exposure to cotton and conditioned taste aversion on lamb weed vs. cotton feeding. Lambs previously familiar with cotton consumed more cotton than lambs with a conditioned taste aversion. Lambs typically selected grass and forbs, while foraging, and selection of cotton was not correlated with selection of herbaceous weeds (r2 = 0.02). Regardless of prior exposure or conditioning, lambs reduced weed cover when compared to ungrazed plots.

Experience from these field research trials underscored the challenge of extrapolating small-plot research to field scale, as sheep grazing behavior is influenced by stocking density. Integrating sheep grazing into production systems shows promise for farmers seeking reduced herbicide/organic management, but further refinement and consideration of economic impacts are necessary. Future research may assess grazing preferences relative to sheep age and breed to provide greater insight into integrated crop-livestock management practices.

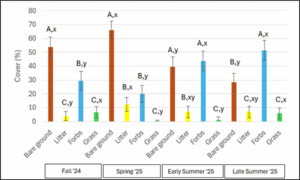

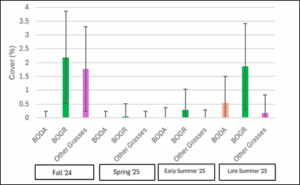

Native perennial forage trials at Lubbock, TX indicated that the ratio of grasses to forbs included in the mix had no main or interactive effect with any other variable. Cover % was influenced by the interaction of sampling date and cover type. Cover by volunteer forb species increased from fall 2024 to 2025, while bare ground decreased. No forbs that were included in the mixes germinated between fall 2024 – fall 2025. The primary volunteer forb species include kochia, Russian thistle, and bitter sneezeweed. Grass cover was also low (< 10%) at each sampling event. Of the three grass species included in the mixes (blue grama (BOGR), buffalograss (BODA), and western wheatgrass), two were recorded in the plots and both are increased in cover as the study progressed. Volunteer grass species included sandbur and windmill grass. Both of these species have decreased in cover since fall 2024. Perennial forage trials at San Angelo demonstrated similar inefficacy of seeding forbs with native grasses, and resulted in primarily side oats grama with sparse buffalograss and considerable broadleaf weed presence, regardless of treatment effects. Across multiple attempts in different years at both locations, establishment of native perennial forages on degraded cropland was very slow, challenged with weeds, and did not result in establishment of the majority of species planted. Forage nutritive value was largely poor, indicating that protein supplementation may be needed if exclusively grazing these forages.

Due to challenges with diverse native species establishment, an additional field trial was coordinated on improved perennial cool-season forage grasses and alfalfa at Wall, TX. Alfalfa resulted in the greatest biomass, followed by tall wheatgrass and tall fescue. Orchardgrass did not yield well, and establishment was poor with intermediate wheatgrass. Trials testing various species and varieties of annual forages indicated that Austrian winter pea and hairy vetch are well-suited among winter annual legumes. Grass legume mixtures were challenged by excessive competition from the grass, and has informed ongoing research on optimum grass seeding rate and planting configuration in species mixtures.

One of the potential benefits of using herbivory for weed control is the savings achieved through reduced herbicide use. Economic assessment indicated that if grazing is successfully used to completely replace herbicide use, this results in a total savings of $105.17 per hectare. The best economic outcome occurred when sheep grazing was implemented at the 8-leaf cotton growth stage to with a lower threshold to terminate grazing (70% weed removal), which aligns with a lower tolerance for grazing damage to the cotton. This resulted in an increase of $198.12 per hectare. In addition to the ecological benefits, sheep grazing as a means of weed control can bear economic merit.

Research components of this work resulted in two graduate research theses, contributing significantly to educational and professional development. Findings were presented at various Extension programs and NRCS workshops, as well as the Texas Sheep and Goat Field Day, Texas Plant Protection Conference, the Beltwide Cotton Conferences, Weed Science Society of America, and the ASA, CSSA, SSSA International Annual Meetings. Development of research and Extension products are ongoing, and outcomes will continue to be shared via field days, newsletters, and local grower meetings.

Objective 1. Employ Neef and Neubert’s six dimensions of participatory research framework to facilitate positive, favorable interaction between researchers and stakeholders and enhance the viability and livelihood of organic cotton stakeholders in the South.

- Coordinate needs assessment via Q-methodology to explore stakeholder perspectives, needs, and expected benefits and outcomes of the proposed project.

- Establish a project advisory board

- Host regular town-hall meetings to convene with stakeholder groups on research progress and direction.

Objective 2. Assess agronomic and stocking management implications of sheep-weeding in cotton

a. Year 1: Evaluate timing of sheep-weeding initiation relative to cotton growth stage, and sheep-weeding termination relative to varying thresholds of weed herbage mass removal.

b. Years 2 and 3: Compare optimized sheep weeding strategy (from Obj. 2a) to alternative and otherwise standard weed management systems.

Objective 3. Identify best-suited perennial and annual forage management options for converted land

a. Test establishment success, forage yield and nutritive value, and soil health indicators across a range of forb inclusion rates with native perennial grasses.

b. Assess forage yield, nutritive value, and sheep grazing preference among summer and winter annual legumes and legume-grass mixtures.

Objective 4. Develop, deliver, and test public resources, economic decision support tools, and stakeholder resources for continued education and assessment of sheep-weeding practices.

a. Economic enterprise budgets informed by measurements in Objectives 2 and 3.

b. Develop and deploy reusable learning modules

c. Publish findings in popular press articles and develop educational videos

Cooperators

- - Producer

- - Producer

Research

Objective 1: Participatory Research

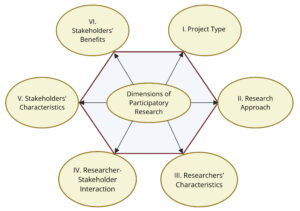

Neef and Neubert’s six dimensions of participatory research framework was employed to facilitate positive, favorable interaction between researchers and stakeholders and enhance the viability and livelihood of organic cotton stakeholders in the South.

Figure 1: Neef and Neubert’s Dimensions of Participatory Research. (Adapted from Neef and Neubert, 2011)

-

Because of the novelty of sheep-weeding in organic cotton, a needs assessment to determine stakeholders’ information and engagement and their expected benefits and outcomes of the project and explore interest, potential for acceptance, and stakeholder experiences regarding the proposed system was conducted. Through the needs assessment, we identified the stakeholders’ perspectives related to sheep-weeding practices in organic cotton farming specifically in Texas. The foundation of Obj 1 was a Q methodology study to measure subjectivity and the “finite diversity” of organic cotton farmers. Communications researchers often used the method as a measurement “for assessing beliefs, attitudes, or values; as an alternative method of data collection in large-sample, public opinion research …; as the basis for assessing connectedness in sociometric or social network research; or as a rating system for observational research” (Stephen, 1985, p. 194). Furthermore, Q method used people to test items, allowed for variance among perspectives (Brown, 1997; Kitzinger, 1987), and provided a method of analysis for explaining the “contextual, discursive, and social” tenets of unique perspectives (Goldman, 1999, p. 592). Because Q methodology allowed the researcher to reveal patterns of perspectives and quantify subjectivity based on items and not people (Killam et al., 2013), it was used in this project to capture opinions and perspectives about sheep-weeding in production in a different and more holistic way than traditional correlational research. Though the number was dependent on the number of statements in the Q set (Watts & Stenner, 2012), our goal was 30 participants in the Q method study with representation across stakeholder groups. We used PQMethod to analyze the data, which included a factor extraction, rotation, and analysis (Killam et al., 2013).

To establish the Q set (statements) used in the Q method study, we conducted qualitative interviews with 10 to 15 organic cotton farmers in Texas, a review of published academic literature, and a review of the notes generated from the advisory board meetings and the town hall meetings. We used Neef and Neubert’s (2011) participatory research framework to develop the interview questions. The questions specifically drew on the attributes of dimension four (involvement of stakeholders in the research process; control of research and centers of decision-making; contribution to the generation of knowledge; type, frequency, and intensity of interaction; and investment of resources and payment) and dimension six (innovations, improved practices; creation of knowledge and awareness; improvement of skills; empowerment and social capital; and improvement of livelihoods). We analyzed the data using Kippendorf’s (1980) content analysis methods.

-

Established a council of researchers and stakeholders to serve as an advisory committee, curate and interpret findings, and carry this initiative beyond the life of the project. The project advisory board, consisting of six members (three producers, two researchers/educators, and one industry professional), served as a council to the project. The advisory board was selected based on their current participation in sheep cropping. The three producers represented three groups: the innovators, early adopters, and laggards. This ensured voices from across Rogers (2003) adoption curve were heard. The other three members of the board were researchers and stakeholders working in the area of sheep cropping. Project PDs met with the advisory board once a year to review the project and get feedback for project improvement. Additionally, the advisory board reviewed the outreach materials discussed in Obj. 4 prior to their dissemination.

In addition, the PDs formed a stakeholder council of innovators or early majority adopters (~10) in using the sheep-weeding to curate and interpret findings and carry this initiative beyond the life of the project. This group, all volunteers, served as advocates of the technology and lead producers in the early/late majority groups. Rogers (2003) defined innovators and early majority adopters as change leaders within their peer groups. This group spoke at two field days (live or virtual) each year of the project and created space for open dialogue about the advantages and disadvantages of technology. Additionally, they were a target audience group for the needs assessment study. Members of the project advisory board and stakeholder council were disbursed compensation for their time and involvement.

-

Hosted online and in-person town hall meetings to facilitate interaction and stimulate conversations among researchers and stakeholder groups (Year 1, 2, 3). We hosted one town hall meeting quarterly in Year 1 and biannually in Year 2 and 3. The meetings included a short 15- to 20-minute program about sheep-weeding practices to increase awareness and provide a platform for interaction and conversation. Length of meetings was determined by depth of conversation and interaction. They were held at Extension offices within organic cotton farming regions of Texas.

Objective 2:

Assess agronomic and stocking management implications of sheep-weeding in cotton

- Year 1: Cotton maturity and grazing intensity – Field trials integrating sheep and cotton in Year 1 were conducted to evaluate the effects of cotton maturity and duration of sheep herbivory on weed suppression and cotton production.

- In Years 2 and 3, a sheep weeding system (identified in Year 1) was compared to other weed management systems. Six treatments (4 replications) will include: 1) no-till sheep weeded, 2) inter-row cultivated + sheep weeding, 3) inter-row cultivated + hand weeding, 4) inter-row cultivated alone, 5) weed-free check (maintained conventionally with herbicides), and 6) weedy check (no weed control). Again, specific treatments are subject to modification at the discretion of the project advisory board, but the spirit of making relevant systems comparisons will be maintained. Planting, maintenance, and measurements will reflect those in Year 1.

- Field experiments were conducted in San Angelo, Texas during the 2022 and 2023 cotton growing seasons at the Angelo State University Management, Instruction, and Research (MIR) center. A travelling irrigator was used persistently in response to the abnormally hot and dry growing seasons in both years, but both crop and weed growth were limited by the environmental conditions. Portable electrified net wire fencing was used to separate plots and contain sheep during grazing events. Electric net fencing also served as a barrier to help keep deer pressure down in the plots. The trial was designed as a 3×3 factorial with treatments including three different cotton growth stages to initiate grazing (4-leaf, 8-leaf, and mid-bloom) and three different levels of grazing intensity (approximately 70%, 90%, and 100% weed removal with presumably greater cotton damage with increasing intensity). Differences were identified using α = 0.1. Each replication also included a weedy-check and weed-free check. To maintain our weed free check (WFC), chemical control was used at the beginning of the season and then manually weeded throughout the season. Our weedy check (WC) had no control. The trial was arranged in a randomized complete block design with four replications. Before and after each grazing initiation, aerial imagery was collected with a UAV. This allowed quantifying weed biomass removal by sheep by analyzing weed canopy cover percentage before grazing and removal after grazing. In 2022, quadrat imagery and clippings were collected (three 0.67 m2 quadrats per plot) as another way to quantify weed biomass removal. Based on evaluation of 2022 physical clipping vs. aerial imagery data, the aerial imagery was determined to better represent treatment effects to whole plot areas, and was continued in 2023. During each grazing treatment, notes were taken every five minutes on the number of sheep grazing weeds, grazing cotton, and how many were idle in the plot. These numbers were converted to sheep grazing hours per hectare (SGH ha-1) to determine, in scalable units, a level of grazing intensity required to accomplish the same amount weed removal. In the first and second initiation timings, sheep were grazed in the plots two or one more time during the season for plot maintenance. To measure final cotton and weed biomass, all cotton plants were harvested from a 3-m length of two center rows per plot, and weed biomass was harvested from the same area, including the interrow space. Biomass was weighed fresh then subsampled (approx. 500 g) for dry matter determination.

- Responses underwent analysis using mixed models in SAS 9.4. While all variables were evaluated within sheep treatments, certain variables were solely assessed where non-sheep checks were irrelevant. These included SGH ha-1 for both weeds and cotton after each treatment, SGH ha-1 for weeds and cotton throughout the season, and the percentage of weed reduction attributed to sheep treatment. Conversely, other responses were examined within sheep treatments and compared to the non-sheep checks. These included weed and cotton percentage over the plot area, the percentage of canopy represented by weeds and cotton, and final weed biomass (kg ha-1) and final cotton biomass (kg ha-1). Among sheep treatments, fixed effects were year, grazing initiation timing, grazing intensity, and all interactions. When compared to the checks, fixed effects were year and treatment. In both cases, random effects were block nested within year, and plot range-row coordinates as covariates nested within year to best account for within-field variability among weed populations. When needed, power transformations were applied to responses according to the Box-Cox method to meet the assumptions of normality and homogenous variance (Box and Cox, 1964). Model estimates were back-transformed for presentation and interpretation. Significant differences were declared at P < 0.1 according to Fisher’s Protected LSD.

- Using Lambs to Control Weeds in Cotton

Upland cotton was planted on a 4-ha plot on the Angelo State University Management, Instruction and Research (MIR) Center, San Angelo, Texas. The test plot was cultivated to eliminate the pre-existing weeds and to provide a seed bed for the cotton to be planted. The cotton was planted on May 31, 2024. The variety used was Phytogen 480 W3FE. The target population planting rate of cotton was 86,450 seeds per ha. After the plot was planted, there was no disturbance to the plot until September, due to the drought conditions that resulted in poor cotton growth and poor weed establishment. Beginning on July 22nd, the cotton was irrigated bi-weekly to allow for optimum growing conditions for both the cotton and weeds.

13 Rambouillet and 10 Suffolk ewe lambs that were 7 months of age were utilized in the study. All twenty-three lambs were randomly assigned to treatments. Three treatments were used in the study. The treatments include (1) lambs averted to cotton “averted group”(2) non-averted lambs that are familiar with cotton “familiar group”, and (3) non-averted lambs with no familiarity with cotton “naïve group” (control). All treatments were exposed to weeds prior to the field study. Prior to the conditioning phase, all lambs were housed on a crop field for 14 days that contains the target weed species. This allowed all lambs, regardless of treatment, to be familiar with the weed species that will be common in the cotton plots.

The plot was fenced off via hot wire fence. The plot was subdivided into 12 separate subplots. Three plots were ungrazed to serve as the control plots. Three plots were assigned to the “averted group,” three plots were assigned to the “familiar group,” and three plots were assigned to the “naïve group.” Each of the 12 subplots were 92.80 square meters.

During the conditioning phase, all lambs were placed in individual pens (1 m by 1.5 m) and fed a basal ration (2.5% BW) to meet maintenance requirements (Table 1). The nutrient content of the basal ration is listed in (Table 2).

Table 1. ASU Ram-20 Basal Ration

|

Ingredients |

% in Ration (As-Fed) |

|

Cottonseed Hulls |

27.5 |

|

Rolled Corn |

33.0 |

|

Alfalfa Pellets |

33.0 |

|

ASU- Premix Mineral |

2.5 |

|

Molasses |

4.0 |

Table 2. Nutrient Content of ASU Ram-20 Basal Ration

|

Ingredients |

% D.M. |

% Protein |

% TDN |

% CF |

% ADF |

% NDF |

|

Cotton Seed Hulls |

91.0 |

8.1 |

34.6 |

45.6 |

65.3 |

79.3 |

|

Corn |

89.1 |

9.1 |

88.1 |

2.3 |

3.6 |

9.95 |

|

Alfalfa Pellets |

90.0 |

17.0 |

52.6 |

26.2 |

34.0 |

45.0 |

|

Molasses |

73.1 |

8.8 |

72.0 |

3.6 |

0.4 |

0.8 |

All 23 lambs were given a seven-day adjustment period to adapt to the housing in individual pens. Once the conditioning phase began on August 13th, the seven “familiar” lambs were fed cotton daily for nine days. The eight averted lambs were fed cotton for nine days and dosed with LiCl (150 mg/kg BW) when intake of cotton remained 100 percent for a two-day period. If the intake of cotton was above zero percent after being dosed with LiCl, the lamb was re-dosed the following day to form a taste aversion. Cotton was fed for nine days and intake was monitored daily. Eight “naïve” lambs only received their basal ration daily. Fresh water and trace minerals were provided ad libitum. A basal ration of Ram-20 was offered at 2.5% BW to all lambs daily regardless of treatment during the conditioning phase to meet maintenance requirements of the lambs (NRC 2007).

The grazing portion of the trial began on September 16th and continued for six days. While foraging on cotton plots, bite counts by plant species were recorded for individual animals. Each animal within a treatment was observed for 30 minutes of foraging. After each treatment was grazed for 30 minutes, the lambs were placed in a pen and fed Ram-20 at 2.5% BW once a day to maintain the energy demands of the lambs. At the end of the grazing trial, line transects were measured to determine the percentage of weed cover on the ungrazed (control) and grazed plots.

Data were analyzed using repeated measures analysis of variance with treatment (familiar, naïve, averted) as the main effect and day as the repeated measure. Lambs nested within treatments served as replications for intake of cotton during conditioning and while foraging on cotton/weed stands. Differences in weed cover at the conclusion of the study were determined by analysis of variance with treatment as the main effect and plots serving as replications. Means were separated using Tukey’s protected LSD when (P ≤ 0.05). Data were analyzed using the statistical package JMP (SAS 2001).

Objective 3:

Identify best-suited perennial and annual forage management options for converted land

Trials were planted at Texas Tech’s Quaker Farm in Lubbock, Texas, in spring 2023 with four mixes (Table 1) in spring 2023. In late winter 2024, due to large-scale weed infestations in the plots at Quaker Farm, we decided we would re-plant plots at Texas Tech’s Native Rangeland in spring 2024. Plots were planted in a randomized complete block design at the Texas Tech Native Rangeland in Lubbock, Texas in May 2024. There were three blocks, and each mix was planted once per block. Individual plots were 8 ft wide and 33 ft long. The plots have received no supplemental water or fertilizer, and we have not applied any mechanical or chemical treatments to control volunteer vegetation since the plots were planted.

Table 1. Mixes planted by Texas Tech personnel. PLS = pure live seed.

Cover and Biomass Sampling

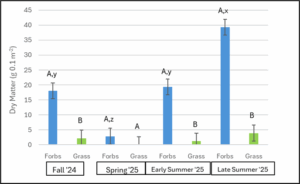

Biomass and cover sampling took place in November 2024 and April, June, August, and October 2025. During each sampling period, cover and biomass measurements were taken using a 0.1 m2 frame along a 10-m transect with cover collected at ~2.5, 5, and 7.5 m and biomass collected at ~2.5 and 7.5 m. Cover categories included bare ground, litter, total forbs, total grass, and individual grass and forb species. Biomass was clipped to the ground level and separated into two functional groups: grasses and forbs. Following drying at 48 – 72 hrs at 60 ºC, biomass samples were weighed to determine dry matter per 0.1 m2. Prior to statistical analysis, cover data were arcsine square root transformed to meet normality requirements. Back-transformed values and 95% confidence intervals are shown in the figures with the cover data (Figures 1 and 2).

Soil Bulk Density Measurements

In fall 2025, soil samples were collected to evaluate the bulk density in the plots and adjacent unplanted, control areas. Samples were collected with an AMS bulk density soil core sampler and were dried for 48 hours at 60 ºC prior to weighing.

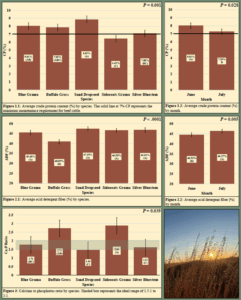

Study of Nutritive Value and Minerology of Native Grass Species

Project Rationale and Description

Due to delays in planting plots and the slow establishment of plantings, we decided to evaluate nutritive value and minerology of native grass species in established native stands in the Texas High Plains and Rolling Plains. The following five native grass species were evaluated: blue grama (Bouteloua gracillis), buffalograss (Bouteloua dactyloides), sand dropseed (Sporobolus cryptandrus), sideoats grama (Bouteloua curtipendula), and silver bluestem (Bothriochloa laguroides). Blue grama and buffalograss were included in our plantings in the grassland rehabilitation study. Sites for plant material collection included the Matador Wildlife Management Area, Paducah, TX (Rolling Plains location) and the Texas Tech University New Deal Research Farm, New Deal, TX (High Plains location). Vegetation has been collected monthly from June to October 2025 by grab sampling to represent the grazing behavior of domestic livestock. Samples collected in June and July have been analyzed, while August – October samples will be analyzed in fall and winter 2025. Crude protein was determined by the LECO Nitrogen and Protein Analyzer by combustion. Acid detergent fiber (ADF) was determined by using the ANKOM 200 fiber analyzer, and mineral content was determined by ICP-OES.

Objective 4: Products and Outreach

- Economic Analysis

Objective four was aimed at the development, delivery, and testing the public resources, economic decision support tools, and stakeholder resources for continued education and assessment of sheep-weeding practices.

Economic analyses compared the incorporation of small ruminants to the current enterprise system of organic cotton production. Key financial variables included forage value, cotton consumption, change in revenue and profitability. Changes in revenue and expenses were calculated in order to give an estimated change in profitability for the different treatment combinations used in this study. Potential changes were examined in the revenue earned in cotton and forage production as well as in the cost differences of herbicides, fencing, labor.

2. Disseminate two reusable learning modules (RLMs)

Objective 1

Exploring How Texas Organic Cotton Producers Make Decisions to Implement Sheep Cropping Techniques

We used a qualitative interview approach to explore how Texas organic cotton producers

make decisions about on-farm use of sheep cropping techniques. Qualitative interviews are often used to study a single case or situation that is small in scope and size but provides valuable evidence that could be used as a foundation to further study in a particular area. For our study, we interviewed five organic cotton farmers in West Texas. These five farmers are part of a small group of farmers who grow organic cotton in the state (~125 farmers). We answered two research questions in our study.

RQ1: What factors do Texas organic cotton farmers consider when making decisions about transitioning to sustainable sheep cropping techniques?

Table 1: List of Themes and Subthemes for RQ1

|

Theme |

Subtheme |

|

Challenges |

Sheep Management |

|

|

Resource Availability |

|

|

Labor |

|

|

Rain/Water |

|

Conservation |

Improve Soil Health |

|

|

Regenerative Agriculture |

|

|

Crop Rotation |

|

|

Too Much Experimenting on Land |

|

Economic Considerations |

Success/Cost |

|

|

Market Conditions |

|

Personal Beliefs |

Perceptions of Research |

|

|

Acceptance of Innovation |

|

|

Personal Conviction |

RQ2: What are information seeking behaviors of Texas organic cotton farmers when making decisions about adopting sheep cropping techniques?

Table 2: List of Themes and Subthemes for RQ2

|

Theme |

Subtheme |

|

Direct Contact |

Local Demonstration/Observation |

|

|

Peers |

|

|

Experts |

|

Growth Through Experience |

Personal Experience |

|

|

Trial and Error |

|

|

Succession |

|

Indirect Contact |

Social Media |

|

|

Books |

|

|

Conferences |

Using Dimensions 4 and 6 of Neef and Neubert’s Participatory Research Framework to Describe Organic Cotton Farmers’ Participation in Research

We used an integrative literature review approach Torraco (2016) to describe the characteristics of how organic cotton farmers choose to participate in research and the benefits they perceive from participating in research projects. Using the interaction attributors of dimension four and benefits attributors of dimension six of Neef and Neubert’s (2011) participatory research framework, we identified descriptors of organic cotton farmers’ participation in research. We developed the research protocol using Torraco’s methods and refined it using Paré et al.’s (2016) guidelines. The sample consisted of articles published between 2006 and 2023 (N=26) that were gathered using Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Research Rabbit. The initial search used the terms “organic cotton,” “sheep cropping,” and “herbicides,” but did not provide a large sample. Thus, we added “livestock cropping.”

RQ1: How is Dimension 4 of Neef and Neubert’s participatory research framework described in the organic cotton farming and sheep cropping literature?

Table 3: Interaction Descriptors for Dimension Four of Neef and Neubert’s (2011) Participatory Research Framework

|

Dimension Attribute |

Descriptor |

|

Interaction type |

I attend the farm field days hosted by county extension. |

|

Grower meetings are valuable for gaining information on improving my production. |

|

|

Grower meetings are valuable for gaining information about new practices. |

|

|

I am open to Extension-based intervention plans that will help me. |

|

|

I am open to virtual workshops and activities. |

|

|

I am interested in receiving a visit from my AgriLife Extension agent to receive recommendations for my operation. |

|

|

I am interested in receiving seasonal calls from my AgriLife Extension agent to receive recommendations for my operation. |

|

|

Programs that frequently provide beneficial scientific information would benefit my operation. |

|

|

I prefer to receive information from experts (i.e., researchers, Extension specialists, industry representatives). |

|

|

I prefer to receive information from influential farmers in my social network. |

|

|

Interaction frequency |

I am interested in receiving seasonal calls from my AgriLife Extension agent to receive recommendations for my operation. |

|

Interaction intensity |

I attend the farm field days hosted by county extension. |

|

I am open to virtual workshops and activities. |

|

|

I am interested in receiving a visit from my AgriLife Extension agent to receive recommendations for my operation. |

|

|

I prefer programs that provide information but minimal agent/consultant involvement. |

|

|

Information type |

I am open to Extension-based intervention plans that will help me. |

|

I am open to virtual workshops and activities. |

|

|

I would be interested in an educational program that caters to farms of a similar capacity to mine. |

|

|

I would like to know more about financial programs related to my operation. |

|

|

Programs designed specifically for the age of my farm interest me. |

|

|

Programs that frequently provide beneficial scientific information would benefit my operation. |

|

|

Resources and payment investment |

Programs that reduce farming costs through equipment and technology interest me. |

|

I would like to know more about financial programs related to my operation. |

|

|

The possible monetary profits of sheep cropping interest me. |

|

|

The possible increased yields because of sheep cropping interest me. |

|

|

I do not see the value of scientific data on my operation. |

|

|

Management of weeds is a top priority for me. |

RQ2: How is Dimension 6 of Neef and Neubert’s participatory research framework described in the organic cotton farming and sheep cropping literature?

Table 4: Benefit Descriptors for Dimension Six of Neef and Neubert’s (2011) Participatory Research Framework

|

Dimension Attribute |

Descriptor |

|

Innovations, improved practices |

Grower meetings are valuable for gaining information on improving my production |

|

Programs that reduce farming costs through equipment and technology interest me. |

|

|

I am interested in using sheep for weed control in my organic production |

|

|

The environmental benefits of sheep cropping interest me. |

|

|

Knowledge and awareness creation |

Programs that frequently provide beneficial scientific information would benefit my operation. |

|

I would like to adopt sheep cropping practices but need help and information to do so. |

|

|

Skills improvement |

I use the information I learn at field days and apply it to my operation. |

|

Grower meetings are valuable for gaining information on improving my production |

|

|

Empowerment and social capital |

My heirs' knowledge about keeping soil healthy is important to me. |

|

The economic benefits of sheep cropping would help my family. |

|

|

Livelihood improvement |

My heirs' knowledge about keeping soil healthy is important to me. |

|

The economic benefits of sheep cropping would help my family. |

Sheep Integration for Diverse and Resilient Organic Cotton Systems: A Q-method Study

We used Q methodology to characterize cotton producers in regards their on-farm decisions. Q methodology is “a research technique, and associated set of theoretical and methodological concepts, originated and developed by William Stephenson, which focuses on the subjective or first-person viewpoints of its participants” (Watts & Stenner, 2012, p. 3). Q methodology is unique in that it incorporates similarities of each to explain rigorous research questions or objective and emphasizes “contextual human subjectivity,” while the statistical components (e.g., correlation and factor analysis) provide rigor (Leggette & Redwine, 2016, p. 58). Our sample includes 22 organic cotton farmers who would be among the population to consider integrating sheep into diverse and resilient organic cotton systems.

RQ1: Identify common viewpoints of organic sheep farmers as they relate to integrating sheep into diverse and resilient organic cotton systems

RQ2: Identify the interaction and benefit descriptors that organic sheep farmers agree are important and not important

Table 5: Q-set of Statements About Common Viewpoints of Organic Cotton Farmers Related to Integrating Sheep into Diverse and Resilient Organic Cotton Systems

|

No. |

Statement |

|

1 |

I value grower meetings for gaining information about new practices. |

|

2 |

I value grower meetings for gaining information on improving my production. |

|

3 |

I am interested in having an AgriLife Extension agent visit to provide recommendations for my operation. |

|

4 |

I am interested in having seasonal calls from my AgriLife Extension agent to provide recommendations for my operation. |

|

5 |

I am interested in using sheep for weed control in my organic production. |

|

6 |

I am open to Extension-based intervention plans that will help me. |

|

7 |

I am open to virtual workshops and activities. |

|

8 |

I attend the farm field days hosted by county extension. |

|

9 |

I do not see the value of implementing scientific data on my operation. |

|

10 |

I prefer programs that provide information but minimal agent/consultant involvement. |

|

11 |

I prefer to receive information from experts (i.e., researchers, Extension specialists, industry representatives). |

|

12 |

I prefer to receive information from influential farmers in my social network. |

|

13 |

I use the information I learn at field days and apply it to my operation. |

|

14 |

I would be interested in an educational program that caters to farms of a similar capacity to mine. |

|

15 |

I would like to adopt sheep cropping practices but need help and information to do so. |

|

16 |

I would like to know more about financial programs related to sheep cropping |

|

17 |

I consider managing weeds a top priority. |

|

18 |

I believe my heirs' knowledge about keeping soil healthy through innovative technologies is important. |

|

19 |

I am interested in programs designed specifically for the age of my farm. |

|

20 |

I believe programming that frequently provides beneficial scientific information would benefit my operation. |

|

21 |

I am interested in programming that reduces farming costs through equipment and technology. |

|

22 |

I believe the economic benefits of sheep cropping would help my family. |

|

23 |

I am interested in the environmental benefits of sheep cropping. |

|

24 |

I am interested in the possible increased yields because of sheep cropping. |

|

25 |

I am interested in the possible monetary profits of sheep cropping. |

|

26 |

I believe the effects of sheep cropping techniques on crop yield is important. |

|

27 |

I believe the challenges of integrating a livestock commodity into my farm operation are too difficult. |

|

28 |

I currently participate in NRCS conservation-based programs. |

|

29 |

I currently participate in USDA conservation-based programs. |

|

30 |

I am aware of the benefits of sheep cropping. |

|

31 |

I read the newspaper to be updated with Extension news. |

|

32 |

I connect with influencers on social media, including YouTube. |

|

33 |

I read books to be up to date on organic farming techniques. |

|

34 |

I attend conferences to learn more about organic farming. |

|

35 |

I use the information I learn from radio (farm reports and updates) on my operation |

|

36 |

I use the information I learn from TV on my operation. |

|

37 |

I use the information I learn from Extension-based communication on my operation. |

|

38 |

I use the information I learn on social media on my operation. |

|

39 |

I need visual evidence from on-farm demonstrations that sheep cropping practices work. |

|

40 |

I am motivated by competition with neighboring farms to implement sheep cropping practices. |

|

41 |

I consider productivity and yield when deciding to implement sheep cropping practices. |

|

42 |

I consider economics when deciding to implement sheep cropping practices. |

|

43 |

I value the opportunity to share information with other producers about sheep cropping. |

|

44 |

I am interested in helping other farmers implement sustainable practices on their operations. |

Objective 2

Both growing seasons so far were extremely hot and dry in West Texas. In 2022, San Angelo experienced the hottest July on record (in 116 years), with an average daily high of 103.5 F and average temperature of 89.7 F. The area received only 3.37 inches of rain from January through July (71% below average for this period). Due to these conditions, all summer annual forage trials failed (as all sites were non-irrigated). In 2023, record high temperatures were observed in June (daily record of 115 F) and the area experienced the hottest August on record. The sheep-in-cotton trial was irrigated as frequently as possible throughout the season, enabling enough plant growth for crop and weed measurements, but water was inadequate for harvestable cotton production in both years.

In the first year of the sheep-weeding trial, grazing intensity had the greatest effect on total weed biomass (p = 0.036), weed canopy (p = 0.024), and the cotton to weed ratio (p = 0.074). The most intense grazing treatment (target 100% removal) at the 8-leaf initiation resulted in 89% and 49% greater weed biomass reduction than the least and moderately intense treatments, respectively. Similarly, the most intense grazing treatment at the mid-bloom initiation reduced weed canopy cover 33% and 80% more than the least and moderate intense grazing, respectively. Final weed biomass was less due to 8-leaf initiation with 100% weed removal (21 kg ha-1) than mid-bloom initiation with 100% weed removal (77 kg ha-1), 4-leaf initiation with 100% removal (180 kg ha-1), as well as the weedy check (244 kg ha-1) (Figure 1). Grazing initiation time had the greatest effect on total amount of sheep grazing minutes required for each plot (p < 0.0001). To achieve the same weed biomass removal as the 4-leaf grazing initiation, 8-leaf and mid-bloom initiations required 46% and 135% more sheep grazing minutes, respectively. As sheep were introduced into each plot, they all were not eating at the same time and/or throughout the entire time in the plot. The SGM unit allows for a more quantifiable metric to determine how long sheep should be grazing in the plot, rather than time (e.g., 30 minutes, 1 hour). Weed management treatments did not influence cotton canopy or final cotton biomass, likely due to a season of severe drought. Timing (cotton growth stage) of grazing initiation also did not influence cotton canopy, cotton biomass, weed biomass, and weed canopy to the same effect as grazing duration.

Figure 1: Sheep-weeding effect on ultimate weed biomass at the end of the 2022 season. Weed canopy coverage before and after grazing at each time and intensity in 2022.

Over both seasons (2022 and 2023) combined, grazing intensity effects were not significant within initiation timings, although a consistent relationship was observed with greater reductions of weed biomass at the later grazing timings, and in the weed free check, compared to the earlier grazing timings and the weedy check (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Sheep grazing timing and intensity effects on ultimate weed biomass compared to a weedy check (WC) and weed-free check (WFC).

As grazing intensity was ultimately insignificant in our measured responses across years, a simplified analysis was conducted comparing only sheep grazing initiation timing to the weedy and weed-free checks. This showed that ultimate weed biomass was reduced in the sheep weeding treatments initiated at the 8-leaf growth stage and mid-bloom, although this reduction of weed biomass did not result in increased cotton biomass (Figure 3). Sheep spent considerably more time grazing weeds than cotton (Figure 4, 5), but as greater herbivory on the cotton occurred at earlier growth stages, we conclude that even slight early-season grazing damage to the cotton resulted in ultimately reduced/compromised yield potential. As the cotton matured, sheep grazed cotton only ~10% of the time compared to ~15% at earlier stages; however, by this point in the season the damage to cotton yield potential via weed competition had likely already occurred.

Figure 3: Effects of sheep grazing initiation timing on ultimate weed vs. cotton biomass compared to the weedy check (WC) and weed-free check (WFC).

Figure 4: Proportions of sheep grazing time spent eating weeds vs. cotton relative to cotton growth stage.

Figure 5: Graduate student Mathew Stewart planting cotton for sheep grazing trials and weed population difference between grazed (right) and non-grazed(left) plot in 2022.

Lamb Conditioning and Grazing Preference

Exposure and Aversion to Cotton

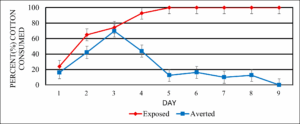

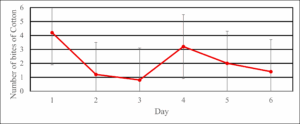

After day 3, intake of cotton decreased (Figure 1). From day 5 through day 8 the intake of cotton remained approximately 15%. This was largely a function of some of the lambs decreasing intake but continuing to consume some cotton. Those individuals were re-dosed with LiCl at the same rate until intake was zero for all individuals. The last lamb was averted to cotton on day 8.

Seven of the 15 lambs were randomly allocated to Familiar treatment. These were also fed fresh cotton daily. Intake increased daily until day 5 of exposure (Figure 1). Thereafter, lambs consumed all of the cotton offered each day. Lambs in the naïve treatment were not exposed to cotton during this phase of the study.

Figure 1. Percent of cotton consumed (intake) during the conditioning phase of this study. “Averted” lambs were dosed with LiCl on day 3 of the study to create an aversion to cotton. “Familiar” lambs were not dosed.

Individual Day Cotton Bite Analysis

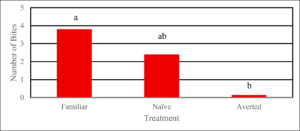

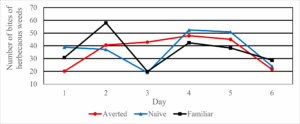

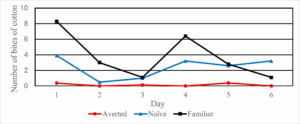

The number of bites of cotton was low for all treatments. Averted lambs took fewer bites of cotton. Conversely, familiar lambs selected cotton more frequently than averted lambs (Figure 2). The number of bites of cotton taken by naïve lambs was similar to familiar and averted lambs. Selection of cotton also differed by day (Figure 3). All lambs, regardless of treatment, selected more bites of cotton on day 1 and 4 of the study.

Figure 2. The mean number of bites of cotton consumed across in each treatment (familiar, naïve, averted) measured per grazing period throughout the six-day trial.

Figure 3. The mean number of bites of cotton consumed across of all treatments by lambs over six days of grazing cotton plots.

The treatment by day interaction also differed for both selection of herbaceous weeds and cotton (Figure 4A and 4B). Regardless of treatment, lambs typically selected herbaceous weeds (grasses and forbs) and avoided cotton (Figure 4A and 4B). The mean number of bites of cotton varied across six-day trial (treatment by day interaction differed) (Figure 4B). When cotton was selected, familiar lambs selected cotton more frequently than averted lambs. Throughout the 6-day grazing trial, the selection of cotton for lambs averted to cotton remained near zero. On day 1, both naïve and familiar lambs consumed cotton. Selection of cotton decreased on day 2 and 3 followed by an increase on day 4. Selection of cotton declined after day 4 for both familiar and naïve lambs. Selection of cotton was not correlated with selection of herbaceous weeds (r2 = 0.02).

Figure 4A. The number of bites of herbaceous weeds (grasses and forbs) consumed over six days for grazing on cotton plots

Figure 4B. The number of bites of cotton consumed over six days for grazing on cotton plots.

Weed Cover

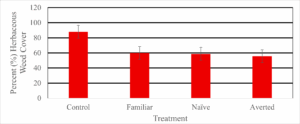

After the grazing trial was completed nine of the grazed plots and three of the non-grazed plots (control) were measured for percent weed cover. After six days of grazing the plots the three treatment plots had similar cover of herbaceous weeds averaging 55 percent to 60 percent weed cover (Figure 5). The ungrazed control plots averaged 87.9 percent in weed cover.

Figure 5. The average percent (%) cover of herbaceous weed cover within the “control,” “familiar,” “naïve,” and “averted” treatment plots measured after the grazing trial.

Objective 3.

The ratio of grasses to forbs included in the mix had no main or interactive effect with any other variable. Cover % was influenced by the interaction of sampling date and cover type (Figure 1). Cover by volunteer forb species has increased from fall 2024 to 2025, while bare ground has decreased (Figure 1). No forbs that were included in the mixes germinated between fall 2024 – fall 2025. The primary volunteer forb species include kochia, Russian thistle, and bitter sneezeweed. Grass cover has been low (< 10%) at each sampling event (Figure 1). Of the three grass species included in the mixes (blue grama (BOGR), buffalograss (BODA), and western wheatgrass), two have been recorded in the plots so far and both are increasing in cover as the study progresses (Figure 2). Volunteer grass species include sandbur and windmill grass. Both of these species have decreased in cover since fall 2024 (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Grass cover percentage of three grass species during Fall, 2024 and Spring, Early Summer and Later Summer 2025.

Figure 2: Volunteer grass cover percentage o during Fall, 2024 and Spring, Early Summer and Later Summer 2025.

Biomass Production

Biomass production was influenced by the interaction of sampling date and functional group (grass vs. forb) (Figure 3). The ratio of grasses to forbs included in the mix had no main or interactive effect with any other variable. Dry matter from volunteer forbs increased from fall 2024 to late summer 2025. During almost all sampling periods forbs produced more biomass than grass. Total grass biomass was similar at all sampling points, but values indicate a numerical increase with time since planting. Similarly, grass species composition is changing as indicated by the cover data.

Figure 3: Biomass production as influenced by the interaction of sampling date and functional groups (grass vs. forb).

Soil Bulk Density

In fall 2025, control areas and planted plots had similar bulk density (av. 1.52 g/cm3). There were no differences observed across different species mixes either.

Forage Nutrition

There was no species × month interaction for crude protein (P = 0.273) or ADF (P= 0.785) .

Sand dropseed had the greatest CP, while side oats grama had the least (Figure 1.1).

Side oats grama was the only species that didn't meet minimum maintenance requirements for dry beef cattle (7% CP).

CP content was greater in June than July, though it met requirements in both months (Figure 1.2).

Buffalo grass had significantly lower ADF than the other species (Figure 2.1).

There was an increase in ADF from June to July (Figure 2.2).

Ca:P ratio varied by species, and sand dropseed did not meet the ideal threshold.

- The lack of an interaction between species and month indicates all species had a similar seasonal response. Decreases in CP and increases in ADF from June to July reflect reduced quality with forage maturation. Buffalo grass had the best overall profile, likely due to its high leaf-to-stem ratio. Although sand dropseed had the greatest CP content, it did not have desired ADF and Ca:P values. This may be due to sand dropseed’s low leaf-to-stem ratio. Results suggest that protein supplementation may be necessary in late summer as CP is likely to decrease below requirements and energy is nearing the minimum threshold for lactation.

Winter Forage Trials

2023 Haygrazer Trials

2023 Yield Summary (Harvest 1)

|

Variety |

Source |

Coleman |

Rowena |

Combined Locations |

|

----------------------- lb ac-1 ----------------------- |

||||

|

Cow Candy |

Coleman Grain |

3771 a |

2230 a-c |

3007 a |

|

P849F |

Pioneer |

3847 a |

2017 a-d |

2939 a |

|

MegaGreen |

Jacoby's |

3375 ab |

2461 a-c |

2924 a |

|

Sugar Graze Ultra |

Turner Seed |

3014 a-c |

2788 a |

2908 a |

|

P859F |

Pioneer |

2519 bc |

2903 a |

2718 ab |

|

P877F |

Pioneer |

2658 a-c |

2658 ab |

2664 a-c |

|

SugarTex III |

Palmer's Seed |

2856 a-c |

2271 a-c |

2570 a-c |

|

Zacate |

Turner Seed |

2983 a-c |

2067 a-d |

2532 a-c |

|

Cattle King |

Coleman Grain |

3026 a-c |

1901 a-d |

2470 a-c |

|

P845F |

Pioneer |

2551 bc |

2174 a-d |

2369 a-c |

|

Hegari |

Turner Seed |

3216 ab |

1427 c-e |

2328 a-c |

|

Super Sugar DM |

Helena |

2532 bc |

1643 b-e |

2094 b-d |

|

Sweeter'n Honey |

Coleman Grain |

2571 bc |

1523 c-e |

2053 b-d |

|

Sugar Queen |

Turner Seed |

2542 bc |

1485 c-e |

2020 b-d |

|

Sweet Bites |

Helena |

2366 bc |

1379 c-e |

1879 cd |

|

Red Top Cane |

Turner Seed |

1909 c |

1160 de |

1541 d |

|

Piper Sudangrass |

Turner Seed |

2411 bc |

651 e |

1538 d |

|

*Within columns, values with the same letter are statistically not different (p < 0.05) |

||||

2024 Haygrazer Trials

All varieties were planted at 500,000 live seed per acre with a small-plot cone drill on 7.5” spacing in 5 × 20-ft plots with four replications.

|

2024 Haygrazer Variety Trial - Locations combined |

|||

|

Variety |

Source |

tons/ac (15% H2O) |

Letter Group |

|

849F |

Pioneer |

2.02 |

a |

|

845F |

Pioneer |

1.68 |

ab |

|

877F |

Pioneer |

1.65 |

ab |

|

Cow Candy |

Coleman Grain |

1.63 |

a-c |

|

MegaGreen |

Jacoby's |

1.51 |

a-d |

|

Cattle King |

Coleman Grain |

1.47 |

a-e |

|

SugarTex III |

Palmer's |

1.45 |

a-e |

|

Super Sugar |

Helena |

1.37 |

b-e |

|

Sweet Bites |

Helena |

1.23 |

b-f |

|

Zacate |

Turner |

1.14 |

b-f |

|

Super Sugar DM |

Helena |

1.09 |

c-f |

|

Piper Sudangrass |

Turner |

1.05 |

d-f |

|

Red Top Cane |

Turner |

0.98 |

ef |

|

Hegari |

Turner |

0.84 |

f |

Objective 4

Publish agronomics, economics, and communication research results with a specific focus on public accessibility. The PDs published Extension publications, disseminated videos focusing on communicating shared values related to sheep-weeding/cropping and its role in environmental sustainability. The videos will follow The Center for Food Integrity’s recommendations for building trust and earning a social license (https://foodintegrity.org/trust-practices/trust-model/). The videos will be hosted on SARE’s Learning and Resources webpage and disseminated through Texas A&M AgriLife’s social media accounts, including those of the individual PDs professional program accounts.

Herbicide costs

One of the potential benefits of using grazing as a form of weed control is the savings achieved by through reduced herbicide use. Texas AgriLife Extension budgets give typical herbicide expenditures for cotton production. The following table, based on these budgets, gives the expected expenditure on herbicide per hectare for cotton production in the region where this study was conducted. If grazing is successfully used to completely replace herbicide use, this results in a total savings of $105.17 per hectare.

Table 1: Herbicide Cost per Hectare

|

Herbicide |

Cost |

|

Glyphosate |

$31.51 |

|

2-4D Amine 4 |

$4.99 |

|

Trifluralin |

$10.21 |

|

Caparol |

$15.57 |

|

Mepiquat Chloride |

$4.32 |

|

Outlook |

$38.57 |

Fencing

The most common pivot size is ¼ mile long and covers approximately 50 hectares. A square plot containing this pivot has a perimeter of two miles or 10,560 feet. The fencing used in this study cost $1.70 per foot. The expected life expectancy of this fencing is 7 to 10 years. This results in an expected cost of per hectare.

Labor

A more complete analysis would consider the changes in labor costs associated with the different weed control methods. This would involve accounting for a decrease in labor use due to less chemical applications as well as the increased labor needed for animal management. These variables, however, were not tracked during the course of this project. For the purposes of this study it will be assumed that the amount of labor needed for using grazing as a means of weed control is not significantly different than the amount required with traditional methods.

Forage

The weeds consumed by sheep in this trial represent a valuable source of forage. For this study it was assumed that the plant matter had a similar nutritional content to Bermudagrass hay. Based on Texas Agrilife Extension budgets, this would put the value of forage at approximately $200 per ton. There was extensive variation in the study both between and within treatments. Weed removal by sheep was calculated in 2022 but not in 2023. This resulted in 4 observations for each treatment combination. The following table give the value of forage gained for these different combinations during the study. The row numbers correspond to grazing timing and the column numbers correspond to grazing intensity. For instance, grazing with timing 1 and intensity 2 resulted in utilization of $14.64 of forage. The average value of forage utilized across treatments was $72.19.

Table 2: Forage Values per Hectare.

|

Timing |

Intensity 1 |

Intensity 2 |

Intensity 3 |

|

Timing 1 |

$26.13 |

$14.64 |

$20.73 |

|

Timing 2 |

$177.33 |

$87.05 |

$43.63 |

|

Timing 3 |

$101.52 |

$107.11 |

$71.60 |

Cotton Consumed

While the sheep in this study did selectively graze more weeds than cotton. They also consumed some cotton plants. In order to analyze the change in cotton production, the weed controls were used as a baseline. Each treatment within a block was compared to the weed control in that block. The decrease in cotton production was calculated as the difference between the weed control and treatment. The current price of $0.63 per pound of lint was used to translate this into financial cost. This methodology gave eight observations for each treatment combination. The average costs of these are given in the table below. The average loss in revenue due to cotton consumption across all timings and grazing intensities was $65.03.

Table 3: Cotton Losses per Hectare

|

Timing |

Intensity 1 |

Intensity 2 |

Intensity 3 |

|

Timing 1 |

$84.76 |

$116.10 |

$16.83 |

|

Timing 2 |

$42.14 |

$69.29 |

$97.30 |

|

Timing 3 |

$67.61 |

$37.97 |

$53.30 |

Economic Summary

Combining the changes in these individual factors gives the expected net change resulting from switching from traditional methods to grazing as a form of weed control.

Table 4. Increase in revenue, cost and net change

|

|

Average Change |

Least Profitable: Timing 1 Intensity 2 |

Most Profitable: Timing 2 Intensity 1 |

|

Increases in Revenue |

|||

|

Herbicides |

$105.17 |

$105.17 |

$105.17 |

|

Forage |

$72.19 |

$14.64 |

$177.33 |

|

Increases in Cost |

|||

|

Fencing |

$42.24 |

$42.24 |

$42.24 |

|

Cotton Reduction |

$65.03 |

$116.10 |

$42.14 |

|

Net Change |

|||

|

|

$70.09 |

-$38.53 |

$198.12 |

The results of the study are promising with an average increase in revenue of $70.09 across all treatments. The worst scenario occurred when sheep were grazed at the 4-leaf stage to 90% weed removal. This treatment resulted in a loss of $38.53 per hectare, compared with chemical control methods. On the other hand, The best outcome occurred when grazing was conducted at the 8-leaf stage to 70% weed removal. This resulted in an increase of $198.12 per hectare. In addition to the ecological benefits, It appears grazing as a means of weed control is also potentially economic advantageous.

Education

Educational goals/deliverables included the two graduate thesis, development and dissemination of two reusable learning modules, six Extension and popular press articles, and two educational videos.

Graduate Research and Thesis Success Story I (Matthew Stewart)

M.Sc. student Matthew Stewart began his research on this project in May 2022, coordinated both years of field research trials integrating sheep into cotton systems, and graduated in May 2024. Matthew shared his research findings at six different academic conferences (photos below): in an oral presentation at the American Society of Agronomy Meetings (Baltimore, MD) in 2022, and as a research poster at the Texas Plant Protection Conference (Bryan, TX 2022 and 2023), the Beltwide Cotton Conferences (New Orleans, LA in 2023 and Fort Worth, TX in 2024).

Matthew Stewart placed 2nd in the graduate student poster competition at Texas Plant Protection in 2022 and won 1st place in 2023, and placed 3rd in the Sustainability Conference at Beltwide in 2023. Matthew completed and defended his thesis and has started a job with a research farm in Georgia. Currently, we are working to submit thesis research as a peer-reviewed scientific publications.

M.S. student Matthew Stewart presenting his sheep weeding research poster at the 2023 Texas Plant Protection Conference.

Thesis by Matthew Stewart submitted for partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science and approved by Texas A&M University.

Available online: https://oaktrust.library.tamu.edu/items/75dbe821-ca4a-40f4-9fbf-56a654379c05/full

Two different M.S. students began working with Dr. Holli Leggette on the participatory research, communication, and outreach components of the project, but both left for reasons unrelated to this project. Another student has helped continue that part of the project, and Dr. Leggette has a plan to involve other students in the process as the work continues.

ASA, CSSA and SSSA Annual Meeting 2022.

Matthew Stewart presented the research work titled " Sheep as a Potential Tool for in-Season Cotton Weed Management.”

Available online: https://scisoc.confex.com/scisoc/2022am/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/143851

Citation: Stewart, M., Noland, R. L., McKnight, B., & Redden, R. (2022) Sheep As a Potential Tool for in-Season Cotton Weed Management. [Abstract]. ASA, CSSA, SSSA International Annual Meeting, Baltimore, MD. https://scisoc.confex.com/scisoc/2022am/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/143851

Beltwide Cotton Conferences, 2023

Sustainability Poster presented by Matthew Stewart at the Beltwide Cotton Conferences.

Beltwide Cotton Conferences, 2025

Abstract presented by Ryan Matschek at the 2025 Beltwide Cotton Conferences.

CANVAS. ASA, CSSA and SSSA Annual Meeting 2024.

Graduate student Ryan Matschek and Matthew Stewart presented the research work titled " Integrated Crop-Livestock Systems for Cotton Weed Management”

Available online: https://scisoc.confex.com/scisoc/2024am/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/162219

Citation: Matschek, R., Stewart, M., & Noland, R. L. (2024) Integrated Crop-Livestock Systems for Cotton Weed Management [Abstract]. ASA, CSSA, SSSA International Annual Meeting, San Antonio, TX. https://scisoc.confex.com/scisoc/2024am/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/162219

Graduate Research and Thesis Success Story II (Colbin Jack Briley)

M.Sc. Student – Colbin Jack Briley

Graduate student Colbin Briley completed his master’s degree and developed the research thesis titled "Using Lambs to Control Weeds in Cotton”

Thesis by Colbin Jack Briley submitted for partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science and approved by Angelo State University.

Dr. Reagan Noland (Texas A&M) and Dr. Cody Scott (ASU) (R-L) examine cotton crop after using sheep as natural weed control in summer 2022.

Dr. Reagan Noland (Texas A&M) and Dr. Cody Scott (ASU) observe lambs during implementation of sheep grazing as natural weed control.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation summary:

One direct consultation was made in the first year with a producer who had integrated similar practices previously and was considering options to continue using sheep on his organic cotton farm, and two consultations were made with producers in the second year. The project team also coordinated with 2 key producers to host RFD-TV America's Heartland film crew who featured SARE with a special feature (reported as an on-farm demonstration). This feature can be viewed here (beginning at 12 minutes 30 seconds): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C6c80w72S0s . The communications team from Angelo State University (collaborating institution) also featured our work in their January 2023 magazine "Fiat Lux" and on their Agriculture Department's website: https://www.angelo.edu/live/news/19128-research-at-the-ranch.

In 2023, this work was presented to two different groups of NRCS professionals at workshops geared toward livestock integration and stewardship (~30 per course). One of these events occurred in conjunction with sheep grazing events, so the participants were able to tour the field trial and observe the sheep grazing in the plots. The project was also shared at the 2023 Texas Youth Sheep and Goat Tour (32 participants on June 2023) and the Texas Sheep and Goat Field Day (~92 participants on August 2023).

| Event | Participants | Description | |

| February 2025 | Texas Farm, Ranch, and Wilflife Expo | 120 | indoor educational program |

| January 2025 | Red River Crops Conference | 60 | indoor educational program |

| August 2024 | Texas Sheep and Goat Field Day | 125 | indoor educational program |

| June 2023 | Texas Youth Sheep and Goat Tour | 32 | in-field demonstration of sheep in cotton |

| June 2023 | Plant Animal Interactions Short-Course | 32 | indoor educational program |

| June 2024 | Plant Animal Interactions Short-Course | 30 | indoor educational program |

| August 2023 | Plant Animal Interactions Short-Course | 31 | in-field demonstration of sheep in cotton |

Learning Outcomes

Project Outcomes

To-date, this project has primarily focused on coordinating field research trials and building relationships with collaborators and stakeholder groups. Actual quantification of project outcomes in terms of knowledge gained and practices adopted will be most evident in the final year of the project. This work has been leveraged for another grant proposal (with NRCS) which is currently pending.

Information Products

- Sheep as a Potential Tool for In-Season Cotton Weed Management

- Integrated crop-livestock systems for cotton weed management.

- Sheep As a Potential Tool for in-Season Cotton Weed Management

- Sheep as a potential tool for in-season cotton weed management

- Using Lambs to Control Weeds in Cotton

- Integration Of Sheep In Cotton Production As A Potential Weed Management