Final report for ONE17-294

Project Information

Raising animals outdoors on deep-rooted, perennial pastures can have significant benefits for the environment, animal welfare, and human health. Yet, today, pastured meat remains a niche market. What would it take to make pastured systems the mainstream model of animal agriculture? And how might scaling up affect land use and the environment? This is a complex problem, involving daunting challenges in production, marketing, and distribution. As a starting point, it’s important to understand just how much land and feed it takes to produce pastured animals, and where some of the bottlenecks for more efficient production may lie.

Working with 11 diversified pastured livestock farms in Pennsylvania, we have found that pastured systems take 2.2 to 3.5 times more total land than confinement systems to produce a unit of marketable meat, when animal groups are viewed separately. However, our data indicate that as integrated systems, multiple animal groups (cows, pigs, and broilers) can work together to use land more efficiently than as separate farming enterprises. Moreover, while they use more land total, they use almost exactly as much annual cropland as analogous confinement systems.

Across our sample farms we found large differences in efficiencies; for instance the pounds of feed grain needed to produce a pound of pork varied by 100% between top and bottom performing farms. These numbers show great potential for these farmers to learn from each other and find shared opportunities for improved land and feed efficiency.

At a regional level, we found that feeding Pennsylvania’s 12.8 million residents with 6 ounces of meat per day through pastured livestock farming would require 2.2 times more acres than confinement systems, although nearly all of the additional land would be in deep-rooted, perennial pastures with soil-building, and water quality benefits. For pastured livestock to become the mainstream method of livestock farming, farmers will need to take advantage of opportunities to boost efficiency, and citizens may need to embrace an overall lower level of meat consumption.

Our objective is to establish shared benchmarks for productivity and profitability on pastured livestock farmers, so that farmers can clearly understand how their performance varies over time and how their farm compares to peer farms. Collaborating farmers will help develop a common recordkeeping framework for sharing data on animal numbers, live weights, and meat yield, as well as data on expenses and revenues, separated by poultry, pig, and beef enterprises.

We will develop a flexible record keeping framework that will allow for paper-based and spreadsheet approaches, but we will also engage participants with modern decision support tools, including FarmOS, an open source farm management application, and Quickbooks, a structured financial record keeping program. Project staff at the Pasa Sustainable Agriculture will help organize this data into community benchmarks for production and profitability that will be shared with the network of collaborating farms through reports, workshops, and field days.

Workshops will involve exploring detailed reports of farm data and benchmarks, identifying common management challenges, and exploring new strategies for improved outcomes. Results will also be shared with a wider agricultural community through field days, a factsheet archived on Pasa’s website and presentation at Pasa’s annual conference.

Raising animals outdoors on deep-rooted, perennial pastures can have significant benefits for the environment, animal welfare, and human health. Yet, today, pastured meat remains a niche market. It’s estimated that less than 5% of the 32 million beef cattle, 5% of the 121 million hogs, and 0.01% of the 9 billion broilers produced in the U.S. in 2017 were raised and finished on pasture. What would it take to make pastured systems the mainstream model of animal agriculture? And how might scaling up affect land use and the environment?

These are complex questions that involve daunting challenges in production, marketing, and distribution. As a starting point, we know that pastured livestock farms must be profitable businesses in order for the pastured livestock market to grow. This means it’s important to optimize the two biggest expense categories for any pastured livestock farm: land and feed. Additionally, it’s important to understand how much land it takes to produce pastured meats, so that we can estimate how much land it would take to scale up production in a given region.

To explore these interconnected questions of efficiency and scalability, Pasa Sustainable Agriculture worked with 10 diversified pastured livestock farms in Pennsylvania to develop feed and land efficiency benchmarks for three of the most common meat animal groups: beef cattle, pigs, and broilers. With these benchmarks, pastured livestock farmers can work to improve efficiency or cut costs.

We also used these benchmarks to offer insight into how different livestock models translate to different land use scenarios for a state or region. With these benchmarks and insights in mind, we can work to better understand what sustainable meat production—and consumption—looks like in practical terms for farms and communities.

Cooperators

- (Educator and Researcher)

- (Educator and Researcher)

- (Researcher)

- (Researcher)

- (Researcher)

- (Educator and Researcher)

- (Researcher)

- (Researcher)

- (Researcher)

- (Researcher)

- (Researcher)

Research

We conducted detailed interviews with 11 pasture-based livestock farms in Pennsylvania raising combinations of grass-finished cattle, pastured pigs, and pastured broilers. All of the farms provide animals with continuous access to pasture, except during farrowing and brooding periods for pigs and broilers. We also consulted the farmers’ 2016 and 2017 records on production, processing, feed rations, and grazing practices.

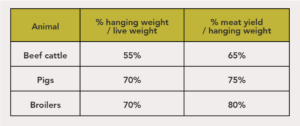

Farmers reported processed animals as an average hanging weight per animal, or the weight of the animal after it has been slaughtered, blood drained, and offal removed. Because the conversion from hanging weight to marketable meat yield varies from processor to processor, we standardized values for converting from live weight to hanging weight, and from hanging weight to meat yield, using values from farmer experience and published references (Table 1). For beef and pork, we estimated meat yield as bone-in retail cuts, while for chicken we estimated meat yield as whole, dressed birds.

Table 1: Processing ratios used to estimate marketable meat yield.

To estimate the total amount of land needed to raise animals on each farm, we inventoried hay purchased off the farm and divided feed mixes for each animal type into their component crops. We then used 2017 Pennsylvania yield data from the National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) to estimate the land area needed to produce these crops. We standardized hay quantities to 87% dry matter. While some of the farmers we interviewed sourced non-GMO feeds, none were certified organic. This is important to highlight since organic crop yields in the U.S. are on average approximately 20% lower than conventional yields, which will tend to translate into lower land-use efficiency for organic livestock operations.

We used an annual time-step to gather and analyze records for each of the 10 farms we examined. Essentially, this means that we accounted for all the animals coming in or out of a farm in a given year, without tracking individual cohorts of animals that may take more than a year to mature (e.g. beef cattle), or that may be born in the fall of one year and slaughtered in the summer of the next (e.g. pigs). We also did not account for feed or hay that may have been stored on a farm over winter, and instead assumed that the winter inventory is fairly constant year to year.

Our benchmarks include land and feed needed to support the entire herd of cattle or pigs, including breeding stock, replacement heifers or sows, and weaned animals that won’t be processed until the following year. For farms that sell or purchase live stocker calves or feeder pigs, we estimated the meat yield “embedded” in those animals based on their live weight at the time of purchase. We then added or subtracted this from the farm’s annual total meat yield.

For each farm and animal type, we estimated a gross meat yield and an adjusted meat yield. The gross meat yield is the marketable meat yield from all animals processed and marketed by the farm in the study year. The adjusted meat yield takes into account the marketable meat embedded in purchased stockers or feeders, or in live animals sold to finish on other operations.

For example, if a beef farm processed 20 animals for a combined hanging weight of 13,000 pounds, we would estimate the gross meat yield as:

= 13,000 LBS. HANGING WEIGHT * (65%) = 8,450 LBS.

If this same farm also bought three stockers from another farm that were about 300 pounds live weight at the time of purchase, then later sold six stockers that were 500 pounds live weight at the time of sale, we would then estimate the adjusted meat yield as:

= [13,000 LBS. HANGING WEIGHT * (65%)] - [3 * 300 LBS. LIVE WEIGHT * (55%) * (65%)] + [6 * 500 LBS. LIVE WEIGHT * (55%) * (65%)] = 9,139 LBS.

For broilers, farmers received days-old chicks from hatcheries, but we were unable to estimate the “embedded” resources required to support hens at the hatchery. Therefore, the gross meat yield and adjusted meat yield is the same for broiler operations.

By taking this annualized approach, we are assuming that 2016 and 2017 were fairly typical years on these farms. If a farm was in the process of significantly scaling up or scaling down its herd size, then the annual time-step approach won’t be accurate. Likewise, if a farm stored significantly more hay or feed over the winter than usual, that could skew our numbers. Still, although the annual time-step approach has these shortcomings, it’s a practical method for benchmarking efficiency using records that most farms can easily maintain. And by averaging over multiple years and multiple farms, we can hone reasonable benchmarks.

Farmers interested in benchmarking their pastured livestock farm’s land and feed efficiency can work with Pasa to calculate benchmarks for their farm using the methods outlined in this resource. Our spreadsheet can be accessed at pasafarming.org/land-feed-benchmarks-worksheet or contact research@pasafarming.org for more information. As more farmers contribute data using these tools, we can improve the accuracy of our benchmarks and help highlight more innovative practices that improve efficiency.

For each animal type, we summarize key benchmarks for feed and land efficiency in the tables below. We also share farm-scale indicators that provide context for the size and structure of each farm enterprise.

Beef Cattle

Feed efficiency

The most efficient of the five beef cattle farms we examined produced 164 pounds of meat per ton of hay, while the two least efficient farms produced 28 pounds of meat per ton of hay.

Land efficiency

The most efficient of the five beef cattle farms we examined produced 71 pounds of meat per acre of pasture and hay acres, while the least efficient farm produced on average 31 pounds of meat per acre.

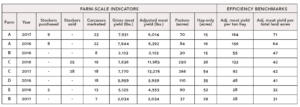

Table 2: Production benchmarks for 5 grass-finished beef farms*

*Many farms harvest some of their hay from pasture acres that they also use for grazing, while also purchasing additional hay from other farms. In this table, “hay-only” acres refers to the acreage needed to produce the additional hay purchased on other farms, while “adjusted meat yield per ton hay” includes all hay fed, including purchased hay or hay harvested from grazing pastures.

Farmer Insight: Locally-Adapted Genetics. Bill Callahan of Cow-A-Hen Farm in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania relies on locally adapted genetics as a key way to boost the efficiency of his pastured cattle herd, which has been exclusively bred on-farm for 25 years (Photo 1). He began his operation with a Holstein dairy herd, and has since brought in Charolais, Simmental, and Hereford genetics through bulls as the herd has become steadily more adapted to the unique environment of his pastures. He carefully selects mother cows based on breeding success and calf survival. While many farms favor cows that birth large calves, because large calves can lead to higher value stocker cattle or to more marketable meat per animal, Bill finds that with smaller calves he has very few problems with cow and calf mortality. Additionally, smaller-bodied animals take less time to mature, helping maintain cash flow on the farm.

Pastured Pigs

Feed efficiency

The most efficient of the eight pastured pig farms we examined produced 0.16 pounds of meat per pound of feed, while the least efficient farms produced 0.08 pounds of meat per pound of feed.

Land efficiency

The most efficient of the eight pastured pig farms we examined produced 1,186 pounds of meat per acre of cropland used to grow feed, while the least efficient farm produced on average 313 pounds of meat per acre of cropland.

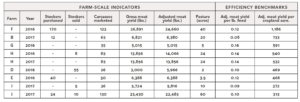

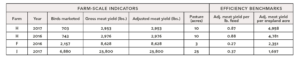

Table 3: Production benchmarks for 8 farms raising pastured pigs.

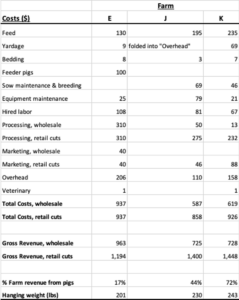

Three farms also shared detailed per-animal production costs and average revenues for their pastured pigs. These data show a range different profitability scenarios for wholesale and retail market channels, with a 111% difference between high and low farms (Table 4). We discussed these numbers in a pastured livestock learning circle at the 2018 PASA conference. Farmers zeroed in on access to affordable/ high quality feed and relationships with processors as consistent factors that determine their profit margins. Access to markets and the ability to efficiently direct market retail cuts were another big factor.

Table 4: Wholesale and retail enterprise budgets for three pastured pig farms.

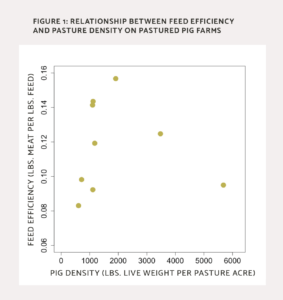

Farmer Insight: Supplementing Feed with Forage. Some farmers in our cohort wondered if pastured pigs can offset their feed consumption by foraging for roots and other resources. If access to pasture did indeed help to reduce feed consumption, we might expect to see a negative relationship between feed efficiency and the density of animals on pasture. Our data don’t support this hypothesis—we didn’t find a significant correlation between live weight per acre of pasture and meat per pound of grain fed (Figure 1). These data don’t prove that pastures can’t be managed in a way that offsets some feed costs; they only show that our sample of farmers weren’t realizing any feed offset from pasture. Moreover, these data don’t speak to other benefits of greater access to pasture, such as improved animal welfare or more nutritious meat.

Figure 1: Relationship between feed efficiency and pasture density on pastured pig farms.

Pastured Broilers

Feed efficiency

The most efficient of the eight pastured poultry farms we examined produced 0.88 pounds of meat per pound of feed, while the least efficient farms produced 0.27 pounds of meat per pound of feed.

Land efficiency

The most efficient of the eight pastured poultry farms we examined produced 4,958 pounds of meat per acre of cropland used to grow feed, while the least efficient farm produced on average 1,697 pounds of meat per acre of cropland.

Table 5: Production records for 3 farms with pastured broiler flocks.

Interestingly, although eight of the 10 farms in our group raised poultry, only three farms were able to generate production benchmark statistics for broilers. Most farmers raising broilers were also raising laying hens and turkeys, and a common practice was to feed all poultry animals from the same feed bins for at least part of the year. Feeding broilers, laying hens, and turkeys all from the same bins makes it impossible to accurately estimate the amount of feed invested in broilers. Although it’s often convenient to feed different poultry groups from a common feed bin, this practice may lead to significant gaps in business planning and enterprise budgeting. Without being able to break down feed expenses by animal group, it is impossible to know if and when poultry enterprises are making or losing money. Developing record keeping practices to separate feed consumption by animal type is an important step forward in making pastured poultry farms more profitable and efficient.

Farmer Insight: Predator Control. Brooks Miller at North Mountain Pastures in Newport, Pennsylvania finds that predator control is a key aspect of an efficient pastured poultry operation. Losses from predators anywhere in the production cycle significantly increases the total amount of feed needed to bring a bird to market. In 2016, Brooks developed a new brooder design using second-hand steel shipping containers (Photo 2). These containers virtually eliminate losses of chicks to weasels, rats, and other predators. He’s also installed automatic feeders and waterers in the brooders. He finds that by keeping feed and water consistently available, chick growth and survival rates have also greatly improved.

What do these feed and land efficiency benchmarks mean for scaling pastured livestock farms to become the mainstream method of meat production?

First, it’s clear that many pastured livestock farms likely have the ability to become significantly more efficient at translating feed and land into marketable meat. In our study, we saw a range of 56%, 74%, and 66% from the least to most land-efficient farms for grass-finished beef, pigs, and broilers, respectively.

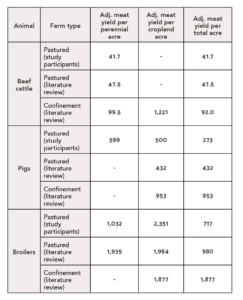

For a more comprehensive comparison, it’s helpful to consider the land efficiency of confinement livestock farms where animals are kept indoors and fed grain. We consulted the scientific literature to summarize results from life-cycle analysis studies for confinement beef cattle, pigs, and broilers, in which scientists have conducted a comprehensive accounting of the resources needed to raise an animal from conception to processing. To put our own land efficiency estimates into context, we also reviewed published life-cycle analyses of grass-finished beef, pastured pig, and pastured poultry systems. Because deep-rooted perennial pastures and hay fields can build soil health and protect water quality, while crop fields used to grow annual grains typically require much more intensive soil disturbance, it was important to distinguish between land efficiency for land used for perennial pasture and hay versus land used to grow annual crops.

Reviewing these numbers, we find that pastured operations are typically much less land-efficient than confinement farms (Table 6). Cattle are by far the least land-efficient animal type, with the all-grass farms typically half as efficient with perennial land than confinement systems that typically blend grass-raised stockers and feedlot finishing phases. Pastured pork farms are approximately half as efficient as confinement pork farms at turning grain and cropland into meat, while our study participants were about 13% more efficient than the pastured systems analyzed in other published studies. Broilers were the most land-efficient animal type, and, perhaps counterintuitively, these data reveal pastured broiler operations may be 5 to 20% more efficient with cropland than confinement operations. This result might suggest that while pastured broilers may grow more slowly or burn more calories moving around on pasture than broilers in confinement, they can also supplement their feed with foraged seeds, insects, and vegetation.

Table 6: Median land-use efficiency for beef, pigs, and broilers.

*Note that conventional beef production in the U.S. typically involves grazing during the calf and “backgrounding phase”, with animals finished on grain in feedlots for the final 160-180 days, or about 25% of their life span. Confinement hog and broiler operations are typically fed grain in confined conditions from birth to processing.

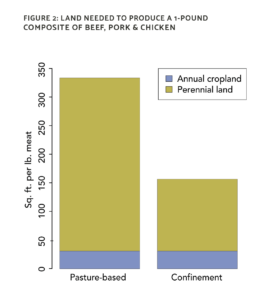

So far, we’ve looked at land use separately for each animal group, but on many pastured livestock farms cows, pigs, broilers, and other animals will interact in ecologically important ways. Pigs or chickens may follow beef cows in different phases of a rotation and work to control weeds, break up pest cycles, and provide additional fertility to the grazing pastures. So, how much pasture and cropland are needed to produce a mix of beef, pork, and poultry meat, given that U.S. meat production is roughly 26% beef, 26% pork, and 42% chicken by total pounds produced? We calculated the amount of land needed to produce one pound of this “composite” mix of meat products on an integrated farm where cows, pigs, and poultry share pastureland, as compared to a one-pound meat equivalent from three separate confinement operations.

Figure 2 shows that while pasture-based farms use more land in total than confinement operations, this additional land is mostly deep-rooted perennial pasture—not annual cropland with potentially associated soil disturbance, pesticide and fertilizer applications, and fossil fuel consumption. In fact, the annual cropland needed by pasture-based farms is almost equivalent to the cropland needed by confinement farms. Essentially, the total land base of a pastured livestock farm might be greater than a confinement operation, but its ecological impact could be considered not only lesser than the confinement model, but can even be viewed as ecologically regenerative in a well-managed system.

Figure 2: Land needed to produce a 1-pound composite of beef, pork, and chicken.

A bigger land-use footprint means more land needs to be devoted to agricultural production. Using Pennsylvania as an example, how many acres would it take for pastured livestock farmers like the 10 in our study to provide meat for all of Pennsylvania’s 12.8 million residents?

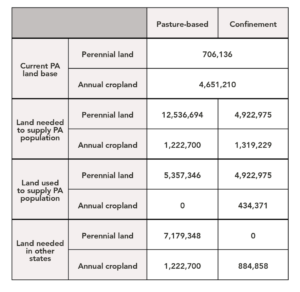

According to the 2017 Census of Agriculture, Pennsylvania has approximately 706,000 acres of pasture-land and 4.6 million acres of cropland. Assuming all residents are consuming the USDA recommendation of 6 ounces of animal protein per day (many probably eat considerably more meat on a given day, some eat none, and nutritionists continue to study how much and what kind of meat is best), a rough calculation shows that we’d need to convert all of the state’s existing cropland into perennial pasture plus we’d need to utilize an additional 7.2 million acres of pastureland and 1.2 million acres of cropland outside of the state to feed all of these animals from farms that hit our average land use efficiency benchmarks (Table 7). In contrast, if all of these animals were raised using confinement methods, we’d need to convert 4.9 million acres of pasture and 434,000 acres of cropland in Pennsylvania, plus we’d need to utilize an additional 885,000 acres of cropland outside of the state—in other words, far less land than the pastured model requires.

Table 7: Current and hypothetical land-use implications (in acres) of producing a meat supply for Pennsylvania’s population.

It’s clear that if we all chose to eat pastured meats, we’d have more land in deep rooted, perennial pastures that protect water and enrich soil. While some of that expanded pasture land would replace cropland currently used to grow feed grains for confinement operations, we’d also have to convert substantial areas of cropland that could be used to grow food grains, veggies, and other crops directly consumed by people. Pastured livestock systems still have plenty of room to scale up in Pennsylvania and nationally as a farming method, but if it is to be our default method of meat production we will also need to make informed choices about how much meat we choose to consume to enable a healthier and more environmentally sustainable model of meat production to succeed.

Education & Outreach Activities and Participation Summary

Participation Summary:

Workshop: Advanced farm management using FarmOS, 4.5.17

Speakers: Brooks Miller, North Mountain Pastures

Location: Village Acres, Farm and FoodShed, Mifflintown, PA.

Farmers need to manage a complex web of information to build a successful business. Pasa Sustainable Agriculture is working to help farmers leverage the power of information using FarmOS, a free, open-source, web-based application for farm management, planning, and record keeping. FarmOS can be flexibility organized to track assets and operations on a variety of farm types, including produce, livestock, and dairy farms. FarmOS can make it easy to track planting and harvest dates, feed inventories, and pest management applications. FarmOS can run on smartphones and tablets, making it easy to stay on top of recordkeeping in the field and make better decisions all season-long.

In this workshop, Brooks Miller helped attendees set up a FarmOS account for their farm and start organizing recordkeeping tasks. Brooks is the co-owner North Mountain Pasture, an 80-acre diversified livestock farm in Perry County, Pennsylvania. Since 2013, he has been using FarmOS to track farm operations, and has found that efficient recordkeeping has really helped improve productivity and profitability. Brooks assisted attendees with getting started in FarmOS and shared some case studies for how this tool has improved his business. He also offered some ideas for how FarmOS can be used to support farmer-driven research and to share knowledge across the sustainable farming community.

9 attendees (9 farmers) , 89% increased knowledge, 100% likely to implement skills or knowledge.

Workshop: Pastured-Livestock Research Group: Boosting Land and Feed Efficiency, 8.30.17

Speakers: Brooks Miller, North Mountain Pastures; Dean Carlson, Wyebrook Farm; Franklin Egan, PASA

Location: Wyebrook Farm, Honey Brook PA

At this workshop, Franklin Egan (Pasa Sustainable Agriculture) shared insights from 2017 research on the land and feed conversion efficiencies of Pasa livestock farms. Brooks Miller (North Mountain Pastures) and Dean Carlson (Wyebrook Farm) lead a discussion about feed conversion efficiency in pastured pigs and explored opportunities to boost productivity and profitability. Brooks Miller also provided a general introduction to FarmOS, a free and powerful tool for organizing farm records and planning for the future.

16 attendees (11 farmers). No evaluations were returned.

Newsletter Article: Can Pastured-Livestock Become a Bigger Part of our Food System?

PASA E-news, 12.13.17.

This e-news was sent to 20,279 email addresses; 2,945 people opened the email, and 215 people clicked-through to the article. Since being added to our blog, a further xx people have accessed this article

Conference Workshop: Learning Circle: Pastured-Pig Costs of Production

Speakers: Brooks Miller, North Mountain Pastures; John Hopkin, Forks Farm; Joanna Michini, Purely Pig Farm.

2.10.18, State College, PA

Pigs are a fixture of many pastured-livestock farms, but knowing the true costs of production is crucial to making pastured pigs work economically. John Hopkins (Forks Farm) and Brooks Miller (North Mountain Pastures) will share detailed numbers for their pastured-pig operations. This will be a discussion, so bring your farm’s expense numbers for feed, processing, labor, and infrastructure, and we will collaboratively explore opportunities to cut costs and increase profits.

27 attendees (18 farmers) , 33% increased knowledge, 100% likely to implement skills or knowledge.

Conference Workshop: Set Your Records Straight: Hands-on Farm Record Keeping Intensive, Speakers: Brooks Miller, North Mountain Pastures; Mike Stenta, FarmOS

2.8.18, State College, PA.

Organizing your records can provide invaluable insight into the patterns and history of your farm, and enable you to boost production and profitability. This workshop will provide a hands-on introduction to farmOS, the open source, community-maintained farm record keeping system. Participants will learn how to map their farm, record their daily activities and observations, and manage their plantings, animals, and equipment. Attendees are encouraged to bring a laptop and will leave with a functional, mobile-ready record keeping system.

38 attendees (32 farmers) , 55% increased knowledge, 72% likely to implement skills or knowledge.

Conference Call: Pastured-Livestock Research Group: Boosting Land and Feed Efficiency Conference Call

Speakers: Brooks Miller, Franklin Egan

Location: Virtual, 8.23.18

During this call, farmers reviewed preliminary benchmark tables for beef, pig, and broiler systems. Farmers expressed interest in the benchmarks and an enthusiasm for continuing to collect data. Farmers were very interested in seeing the enterprise budgets for pastured pigs, and wanted to see more financial benchmarks. This led to discussions about some common expense and revenue categories for accounting. Following this call, Brooks and Franklin produced some template spreadsheets for people to use, although we’ve so far had limited luck getting farmers to use them.

11 attendees (11 farmers). Evaluations were not collected for this event.

Field Day: Pigs on Pasture, Hogs in Hedgerows

10.23.18. Blackberry Meadows Farm

Natrona, PA

This workshop explored how to incorporate pastured pigs into a vegetable operation for production and profit, but also for working activities like clearing brush and making use of wastes and fallen fruits and nuts. Host Greg Boulos from Blackberry Meadows Farm showcased how they fit pigs into their vegetable farm, while also highlighting the usefulness of the Pasa Sustainable Agriculture research project for tracking meat yield and feed consumption by the pigs.

17 attendees (9 farmers) , 88% increased knowledge, 100% likely to implement skills or knowledge.

Conference Workshop: Learning Circle: Pastured Livestock

Speakers: Franklin Egan, Pasa

2.8.19, Lancaster, PA

Land and feed costs are typically among the biggest expenses in a pastured livestock operation. Through Pasa’s Pastured Livestock Land and Feed Efficiency research project, Pasa farmers are benchmarking production and costs to learn what’s typical - and what’s possible- raising poultry, pigs, sheep, or beef on pasture. In this learning circle, we’ll share some preliminary data and troubleshoot opportunities for cutting costs and improving efficiencies, while respecting the land, animals, and people that make a farm work.

23 attendees (18 farmers), 0% increased knowledge, 50% likely to implement skills or knowledge.

Conference Workshop: Set Your Records Straight: Hands-on Farm Record Keeping Intensive, Speakers: Brooks Miller, North Mountain Pastures; Mike Stenta, FarmOS

2.9.19, Lancaster, PA.

Organizing your records can provide invaluable insight into the patterns and history of your farm, and enable you to boost production and profitability. This workshop will provide a hands-on introduction to farmOS, the open source community-maintained farm record keeping system. Participants will learn how to map their farm, record their daily activities and observations, and manage their plantings, animals, and equipment. Attendees can bring a laptop and set up their own farm in the workshop.

17 attendees (17 farmers) , 67% increased knowledge, 83% likely to implement skills or knowledge.

Field Day: Land & Feed Efficiency on Pastured Livestock Farms

7.10.19. Cow-A-Hen Farms

Lewisburg, PA

Bill Callahan, a contributor to Pasa’s Pastured Livestock Land & Feed Efficiency Study, has pasture-raised poultry, pigs, and cattle at Cow-A-Hen Farm for more than two decades. During this field day, he shared his effective, low-tech approach to keeping the comprehensive records he needs to monitor and evaluate the efficiency of his operation. We also explored some of the opportunities and challenges at the farm for improving efficiency and profitability, including developing pig farrowing systems to reduce weanling mortality, cattle breeding strategies to help the herd adapt to the farm, and using an innovative pastured-broiler pen designed to substantially reduce predation on a farm surrounded by woodland. We concluded the afternoon by reviewing Cow-A-Hen Farm’s finances and discussing what constitutes true profitability on a family farm.

16 attendees (10 farmers) , 30% increased knowledge, 67% likely to implement skills or knowledge.

Conference Workshop: Raising Happy, Healthy Organic Pigs on Pasture

2.5.20, Alice Percy, Treble Ridge Farm

2020 Sustainable Agriculture Conference, Lancaster, PA

Author and farmer Alice Percy provided an in-depth introduction to the nutrient requirements of hogs, intensive and extensive pasture systems, breeding and genetics, and hog healthcare. Percy drew on her own farm experience and data from Pasa’sPastured Livestock Land and Feed Efficiency Study to benchmark weight gain to feed input targets for hogs and to appraise strengths and limitations of different hog ration approaches. Percy also stressed record keeping for feed expenses, production, and survival as an essential strategy for farm success.

19 attendees (19 farmers) , 55% increased knowledge, 100% likely to implement skills or knowledge.

Two of the four educational tools identified above were incorporated into the final bulletin and benchmark calculator spreadsheet:

Bulletin:

Scaling Up Pastured Livestock Production: Benchmarks for Getting the Most Out of Feed & Land

Summarized land and feed efficiency benchmarks for grass-finished beef, pastured pigs, and pastured broilers. Explores the implications of these benchmarks for scaling up pastured livestock to become a dominant method of livestock farming in Pennsylvania.

PASA-2020_Scaling-Up-Pastured-Livestock-Production

Benchmark Worksheet:

A spreadsheet tool that farmers can use to calculate benchmarks for land and feed efficiency for grass-finished beef, grass-finished sheep, pastured pigs, pastured broilers, and pastured turkeys. Farmers can compare numbers from their farms to peer benchmarks and share their responses with Pasa Sustainable agriculture as part of a collaborative research project.

PASA-2020_Pastured-Livestock-Efficiency-Benchmark-Worksheet

Learning Outcomes

Our events reached 182 people, including 143 farmers. We measured changed in self-assessed change in knowledge following events using a paper evaluation survey. 53% of respondents reported a moderate or considerable improvement in knowledge against 1-3 learning objectives. We also asked farmers about their likelihood of applying skills or knowledge they learned at the event to their own operations. 84% of respondents reported that they were likely or very likely to apply skills and knowledge.

Key areas in which farmers reported changes in knowledge, attitude, skills and/or awareness

How to set up systems for tracking production and management records. 54% reported a moderate or considerable increase in knowledge.

How production and management records are necessary to understand which enterprises on a farm are making or losing money. 33% reported a moderate or considerable increase in knowledge.

Primary factors affecting profitability in pastured pig production systems. 47% reported a moderate or considerable increase in knowledge.

Different viewpoints for defining and achieving financial viability. 33% reported a moderate or considerable increase in knowledge.

Project Outcomes

A primary organizing question for our project was "how much land does it take to produce a unit of marketable meat using pastured livestock systems." Our project added much needed data to assess the land use footprint of pastured livestock systems. (Table 6). In addition to a breakdown of land use footprints for animal groups separately our data also offers a unique look at the land use, in terms of arable and pasture land resources, of mixed livestock groups as a whole (Figure 2). We also highlighted key areas where this can be improved, namely feed efficiency, pasture management, and genetics and breeding systems. Moveover, our data highlights substantial range in feed efficiency and other metrics across farmers, indicating the potential for substantial knowledge transfer and peer-to-peer learning in this community.

Although all of our collaborating farmers and many event attendees found these data valuable and interesting, changes in farmer practice were harder to achieve. Our project highlighted several record keeping gaps that probably impede effective business planning and decision making, namely that many farmers are unable to track feed inventory and consumption by animal group. Most farmers in our cohort expressed an interest in tracking this information, but were unable to successfully implement protocols to do so on their farms. We introduced over 80 farms to FarmOS as a record keeping tool, but only 2 livestock operations have consistently implemented the tool on their farm.

A few success stories on the record keeping front: one farmer was able to start separately tracking pig feed consumption from poultry feed consumption in 2017 after our interview process in 2016. Another farmer determined that broilers were not a sufficiently profitable enterprise after working with us to separate out turkey from broiler feed consumption. He discontinued his broiler enterprise in 2019, and is focusing on pigs, turkeys, and sheep, and he is happy with improvements to quality of life and income.

This project helped Pasa successfully apply for several grants supporting new benchmarking initiatives addressing soil health and financial viability:

- Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture Research Grant, “Building soil health and climate resilience through on-farm citizen science.” 2020-2021. $73,683.

- Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture Research Grant, “Improving farm viability through collaborative financial benchmarking.” 2020-2021. $71,268.

- Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture Research Grant, “Connecting soil health and best management practices with on-farm citizen science.” 2019-2020. $60,000.

- Conservation Innovation Grant, Natural Resources Conservation Service, “Setting and exceeding community benchmarks for soil health.” 2018-2021. $200,327

Although these grants do not directly address the livestock efficiency benchmarks explored in this project, they all involve benchmarking and apply perspectives on farm-based research and record keeping gained through this SARE project.

In terms of lessons learned and revisions to this project, I feel that we were far too optimistic about the record keeping systems farms would already have in place, and about our ability to work with farmers to implement better systems. Through direct consultation with our 11 core group of farmers, we identified many gaps in record systems, but lacked the needed staff time to persistently follow up with farmers and set up enduring habits for data management. In fact one farmer told us, "maybe you can just set up a bookkeeping service" and we'll pay you to do that. Many farmers appear to need intensive, ongoing support to improve their record keeping systems to understand if/how they are making a profit. We are excited by our ongoing partnership with farmOS and a new Farm Vitality grant program announced by the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture as potential opportunities to provide this in-depth work. At the same time, among the 11 farmers that directly participated in this study, we have successfully engendered a deeper appreciation of the value of detailed records, and to what numbers are truly valuable to track.

Despite some frustrating gaps in data on some farms, we were nevertheless able to assemble a valuable dataset, and we feel we have provided some fresh insight to our research objectives of understanding the potential to scale-up pastured livestock production. Farmers and service providers across the northeast would benefit from these data and the record keeping templates we have provided. Farmers nationwide would benefit from FarmOS as a record keeping tool and framework. Food system scientists and policy makers working to understand the "scalability" of pastured livestock systems would benefit from our data.