Final report for ONE17-301

Project Information

Five farmer landowner groups were offered conversations facilitated by a mediator. Each group was offered four sessions. The targeted farms needed to have their primary operation on leased land. Participant farms were in the beginning farmer phase (1-5 years in business).

Each landowner and farmer group had an initial one of one conversation to share concerns and discuss issues and topics they wanted to address in the sessions with the mediator.

None of these groups were seeking mediation at the time. Groups were navigating lease relationships. It was not hard to find groups willing to participate- of the five I reached out to five were willing to participate and viewed it as an opportunity for support.

Of the five participating farms three used four sessions, one used three sessions and one used one session. Farmers and landowners reported that working with the mediator was a positive experience.

This study outlines the themes and topics that groups discussed. It normalizes the tensions and discussions inherent in a lease relationship- both with themes that would come under a legal written lease and the more interpersonal relational issues that don’t show up in a formal lease agreement.

This pilot project created a discussion guide and two worksheets to guide initial conversations between a mediator and landowner or farmer. This project produced a webinar designed to train mediators in the farm lease context.

Over the course of this pilot project the Coalition of Agricultural Mediation Programs (offering mediation to farmers in 41 states) were granted case expansion to include lease mediation. Lease mediation is now an easily assessable free service available to farms nationally. This may be the first research into the value of lease mediation- and is significant as a first study.

Given our experience we know that mediation is useful for farmers and landowners when both parties are willing to work with a third party neutral during a crisis or conflict. Mediation is generally used as a conflict intervention tool for crisis.

A mediator’s skill can also be used proactively to help parties avoid or manage conflict. Mediators are trained to help parties discuss complex substantive issues, including those when emotions are high. They are experts in facilitating collaborative planning. This project delves into applying mediation as a preventative intervention pairing landlords and farmers with a mediator to facilitate dialogue in what we are terming lease mediation. Proactive lease mediation could be an effective support system for farmers and landowners to strengthen their partnership to work collaboratively and to address conflicts that will inevitably surface.

Leasing is important strategy for farmers at all stages. Leasing land helps beginning farmers affordably access land to start a farm without taking on mortgage debt. Many new farmers, often from non-farm backgrounds, lack the funds to cover the costs of land, equipment, and operating all at once. The National Young Farmers Coalition’s survey of 1000 young farmers (2011) reported access to land (68%) and working capital (78%) as top obstacles to beginning farmers. Leasing a farm can have a significant impact on a farmer’s ability to get started. For established and scaling up farmers as well, leasing offers year-to-year flexibility, access to better land and infrastructure, while keeping scarce capital available for other business investments. There are both successes and failures with lease arrangements. Often whether a situation works out for the farmer and the landowner hinges on their ability to communicate well and resolve differences. “The relationship between the landowner and the farmer is always more important than the written document…” (From Farmland Tenure and Leasing, A Legal Guide by UVM Center for Sustainable Agriculture). When farmers have relationship breakdowns with landowners on their primary farms – and are either forced to relocate or choose to - they confront major financial and business setbacks. A failed lease situation hampers a farmer’s ability to not only establish and grow a stable business, but also to build equity. Leases are a practical tool for farmers to get started, but the lease relationship can be complicated. New York State Agricultural Mediation Program (NYSAMP) is seeing an increase in requests for lease mediation. Sometimes both parties are willing to mediate and reach workable solutions. Other times relationships are too far deteriorated and one party is unwilling to come to mediation. While data on the cost of failed lease situations is lacking, given the prevalence of leasing in the farm economy – and the importance of leased land to beginning and established farmers – the costs are likely to be high. More support is needed for both farmers and landowners beyond the initial stage of establishing a tenant-landlord relationship.

Leasing a farm can have a significant impact on a farmer’s ability to get started. Often whether a situation works out for the farmers and the landowner pair comes down to their ability to communicate well and resolve differences.

Mediators help define issues, emphasize common goals, keep conversations focused, facilitate the development of discussion and of options. NYSAMP currently mediates leases when there is a crisis or breakdown in farmer landowner relations. When both parties are willing to come to the table mediation has a high success rate. This project will offer mediation for maintaining communication rather than for addressing a crisis, to farmers and landowners in quarterly meetings. These case studies will allow us to gauge the value of using mediation at the front end of a relationship.

In addition to the direct mediation services, this project will produce educational materials for training mediators in understanding farmer landowner needs and interests. This project will produce educational materials for the landowners and farmers to reflect on and review their current working relationships. These educational materials will be shared through NYSAMP and Land For Goods websites. Results of the pilot project will be shared widely through NYSAMP, Land For Good, Hudson Valley Farmlink (American Farmland Trust), and through Cornell Cooperative Extensions Beginner Farmer programing. In addition materials and results will be shared with the Coalition for Agricultural Mediation which has programs in 30 states.

Cooperators

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

Research

To date we have completed the four sessions with three sets of farmer- landowner pairs.

A fourth farmer and landowner pair completed one session with positive outcomes. The farmer and landowner will not need the rest of their sessions due to some restructuring of the farmers business. This restructuring involves taking on a retail location which is distant from the current farm location. They expect potential changes to the farm due to this new venture.

Our last set of farmers has used two sessions and would like to use the final two as well but have been focused on business restructuring process. They have moved from a farm co owned by three farmers to a farm co-owned by two farmers and have just finalized that restructuring for the new year. We will be scheduling final sessions this spring.

April to July 2107

Recruited farmer/ landowner pairs in NY and NH

LFG- created webinar to train mediators in lease context and created discussion materials for farmers and for landowners

NYSAMP and LFG reviewed, trialed and revised materials

LFG materials completed

Mediator preparation and training with webinar with discussion session (7/12/17 -1

mediator, and 2 NYSAMP staff for review)

August-September 2017

Mediator preparation and training with webinar with discussion session (9/26/17 -4 mediators)

Decided to include intake process with farmers and landowners meeting with mediators first separately

initial intakes and first mediation sessions

October -December 2017

intakes and mediation sessions (detailed below)

To date all five farms participating have had intake sessions with their mediator. These sessions were an opportunity for the farmer/ farmer co-owners to speak with the mediator and share concerns and goals they have for the mediation sessions. In addition the mediator was able to review the Farmers Worksheet; Initial Questions.

Laurel Schulteis and Micah Witri: (8/6/17)

Jeff Backer and David Viola: (8/29/17)

Maggie Cheney, Angela Defelice and D. Rooney: 10/02/17

Aviva Skye: 11/03/17

Jenny Parker, Aliyah Brandt, Lauren Jones: 11/03/17

To date all five participating landowner teams have had intake sessions with their mediator. These sessions were an opportunity for the land owners to speak with the mediator and share concerns and goals they have for the mediation sessions. In addition the mediator was able to review the Landowners Worksheet; Initial Questions.

Carol and Steve Sullivan and Rich Sullivan (8/7/17)

Carl Wallman (8/31/17)

Brooke Lehman and Gregg Osofsky: 10/05/17

Laura Sink: 10/30/17

Joanna Tipple: 11/03/17

To date three farmer/ landowner teams have had their first two facilitated mediation sessions.

Laurel Schulteis and Micah Witri (farmers) and Carol and Steve Sullivan and Rich Sullivan (landowners)

session one: 08/07/17

session two: 11/16/17

Jeff Backer and David Viola (farmers) and Carl Wallman (landowner)

session one: 10/05/17

session two: 11/28/17

Maggie Cheney, Angela Defelice and D. Rooney (farmers) and Brooke Lehman and Gregg Osofsky (landowners)

session one: 11/14/17

session two: 11/21/17

To date one farmer/landowner team has had its first facilitated mediation session.

Aviva Tilson (farmer) and Laura Sink (landowner)

session one: 12/4/17

To date one more farmer/landowner have first session scheduled.

Jenny Parker, Aliyah Brandt, Lauren Jones (farmers) and Joanna Tipple (landowner)

session one: 01/08/18

In total their have been ten initial meetings (intake sessions) and seven mediation sessions. The remaining thirteen mediation sessions will be scheduled in 2018 with the majority of the sessions occurring during the winter.

January- August 2018

After deciding to include a more elaborate intake process then initially planned and getting a late start, we were able to catch up on our proposed timeline and finished up some of up some mediation sessions over the winter. We are experiencing some delays due to farmer circumstances and requests around timing with one farm.

These farmers would like to use the final two but have been focused on business restructuring process. They have moved from a farm co owned by three farmers to a farm co-owned by two farmers and have just finalized that restructuring for the new year. We will be scheduling final sessions this spring.

Jenny Parker, Aliyah Brandt, Lauren Jones (farmers) and Joanna Tipple (landowner)

session one: 01/08/18

session two: 3/26/2018

session three: 1/29/2019

Maggie Cheney, Angela Defelice and D. Rooney (farmers) and Brooke Lehman and Gregg Osofsky (landowners)

session three: 02/15/18

session four: 03/30/18

Laurel Schulteis and Micah Witri (farmers) and Carol and Steve Sullivan and Rich Sullivan (landowners)

session three: 02/22/2018

session four: 08/20/2018

Jeff Backer and David Viola (farmers) and Carl Wallman (landowner)

session three: 02/08/2018

session four: 05/09/2018

August- September 2018

Not too much happening at this time. Communicating with farmers in a business re structure re preferences around participation and timeline of this project.

October-December 2018

Project coordinator collecting evaluations and notes from each session and beginning to write up case studies for each farm that will be used to evaluate the overall impact of the program and possible future directions. These will be part of the final report. Reaching out to partners with brief updates and reminders that we will meet to discuss the project this spring.

January -March 2019

Finished third session with Ironwood Farms and decided this would be the last due to pressing issues going into the season with a co-owner business restructure and both current owners having new babies and challenges around these changes needing to be prioritized.

April-June 2019

Reviewed cases with Claudia Abbott-Barish our NYS mediator to go through session notes for each farm. Identified themes. Met with Cara Cargill of Land For Good and NH Agricultural Mediation Program to review cases and identify themes. Wrote up initial descriptions of themes and sorted issues and items into each theme across farms.

I discussed the confidentiality issues with both mediators and decided to present aggregated details. I also include individual case studies which share some details but not all since materials will be public and many of the conversations were personal in nature. While it would be easier to write up each case study as a very specific detailed story, it feels more respectful to the farms that participated to offer a more general case study. To be meaningful and nuanced enough and to be useful to those that might like to learn from this work I list out specific types of examples that were discussed for each theme.

Introduction

A core tenant of the mediation process is confidentiality. While farmers and landowners agreed to participate in this pilot project, and are a part of the research effort, many of the conversations that occurred mixed business and personal content. For this report, data points are sorted into themes (Part I and Part II) and are not attributed specifically to any group. This is to preserve some of the confidentiality that is a core tenant of the mediation process, while also giving the reader a nuanced understanding of the themes through specific details.

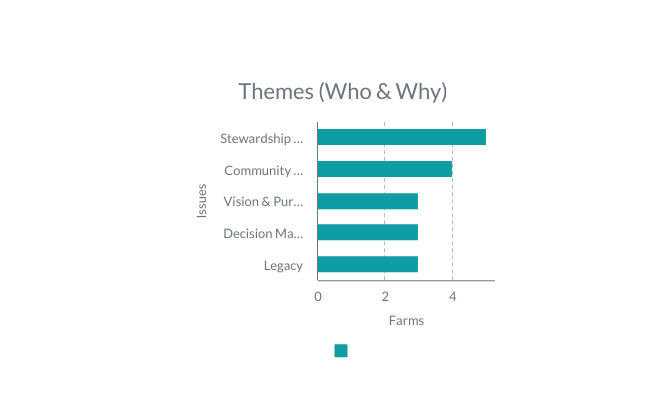

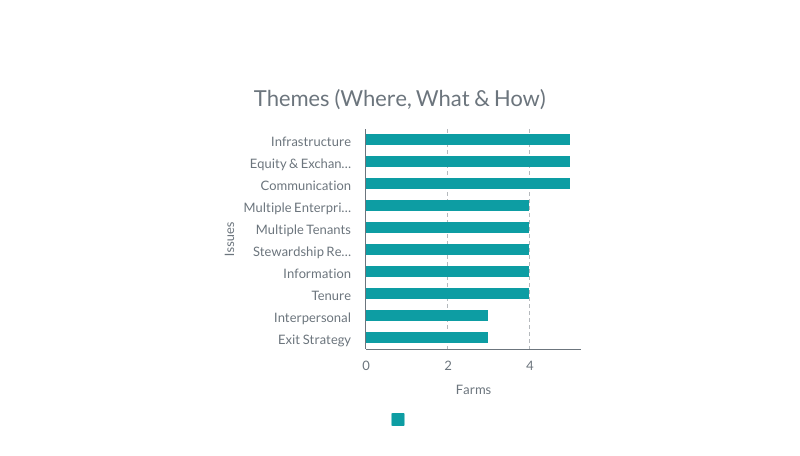

Part I identifies themes related to the questions of who and why. Part II identifies themes related to the questions of where, what, and how. Each theme is described and then followed by several examples of specific conversations. The graphs show the number of farms and their discussions—showing what fell under which theme.

Part III details outcomes by farm, with an overview description of the farmer’s operation and the landowner’s connection to the land, as well as a sense for some of the content that was discussed. A few also include an update at the end.

Part IV discusses the themes, outcomes and other findings. Part V offers some conclusions and ideas about further inquiry.

Part One: Themes-Big Picture (Who & Why)

Stewardship Values: Stewardship as a value pertains to “care” and might include conservation or best practices in production. It might also simply mean whether a property looks cared for, visually. Ideas around stewardship are often subjective and implicit. Groups worked to gain clarity on what stewardship meant to each person and made explicit any unexpressed assumptions, which both farmer and landowner had considered, around what it means to care for the land.

Some of the stewardship values included conservation, soil health, and water quality protection. Others are related to the care and upkeep of the property and to a sense of beauty, cleanliness, and overall order of farm operations.

For example, an unmown hedgerow could meet the farmer's values for biodiversity but might not meet the landowner’s need for order and care around the property. Another example is a landowner wanting the cows to be fenced off from a brook in a wintering area, to maintain good water quality.

Community Dynamics: Exploring and articulating needs and desires around the farm’s relationship to their community. Examples of issues discussed include:

- Landowner wanting to make sure neighbors are not negatively impacted by pigs being raised on the farm.

- Landowner wanting to make sure the public has access to a trail that crosses through a field.

- Discussions and concerns around hosting educational or public events on the farm.

- Farmer’s concerns for CSA customers at pick-up, and for farmworkers with neighbors shooting guns and riding ATV’s.

- Discussions around maintenance and landscaping issues, related to community’s first impressions of the farm.

- Discussions about maintaining productive relationships within the local community.

Vision & Purpose: Articulating and identifying the farmer’s & landowner’s vision and purpose. Examples of issues discussed include:

- Landowners articulate how meaningful it is to be able to help a new generation of farmers get started.

- Landowners have a vision of the land as a sanctuary for agricultural tourism, though this had not yet been achievable.

- Landowners would like the farm to be contributing as a healing element within the community.

- Conversations deepened to discuss a shared purpose, leading to improved relations.

- Farmers and landowners discover a shared purpose and a mission for social justice.

- Discussions around vision lead to a farmer joining the landowner’s stewardship and conservation group as a guiding committee member

Decision-Making: Clarifying who the decision-makers are and what the process and key relationships for decision-making are. Examples of issues discussed include:

- How decisions are being made around access to land or infrastructure use, and who is included in the decision-

- Landowner’s concerns because the farm they were making agreements with is a co-operative farm and the “who” of the farm may change over time.

- Landowners identified that they were the key decision-makers in the day-to-day relationship and that their children (heirs) would be the key decision-makers for any long-term tenure issues.

- Clarified key relationships in decision-making when multiple enterprises and/or tenants were involved.

Legacy: This has to do with vision and intention in terms of something created or maintained for the next generation.

Three of the landowner groups were actively working on legacy issues and were in the process of trying to protect the land for future generations, with trusts or easements.

Part Two: Themes (Where, What & How)

Infrastructure Issues: All the groups used discussion time to sort out issues and expectations around the use of buildings and equipment. Farm maintenance and upkeep, capital improvements to the property, and who would pay for what was also negotiated. Groups shared concerns and cleared up any misunderstandings. Groups navigated and decided on dollar contributions, labor, and timeframes. Sometimes groups needed to gather and share information to be able to move forward and to make decisions. Examples of discussions are broken into four categories: water issues, access roads, buildings and structures, and equipment.

Water Issues

- Repair and maintenance of a well pump

- Discussions on buying a new well for the farm

- Repairs for an existing well

- Discussions around a pond used for both irrigation and swimming, which ran low in a drought year. Information gathering and sharing helped to determine the impact on the pond level from irrigating and helped to inform agreements around usage. This group also crafted contingency plans for drought conditions, for when water resources run low in the future.

- Drainage issues

Access Roads

- Pothole repairs and maintenance

- Building a new road for CSA access to the farm—giving landowner more privacy.

- Laying gravel on a dirt access road for farm customers and delivery

- Snowplowing

Buildings & Structures

- Discussions on how to split the cost of repairs and improvements for existing infrastructure.

- Landowner wanting to be able to approve any building or structure of a permanent or temporary nature.

- Discussion around the responsibility of major repairs (above $500) and minor repairs (under $500).

- Clarifying expectations around building maintenance responsibilities

- Farmers being responsible for any structures they install or construct

- Residential structures for farmer or farmworker housing

- Discussions to gain clarity on financial costs for repair and maintenance of the farm buildings and vehicles.

- Discussions around the need for cold storage

- Permanent pasture fencing

Equipment

- Tracking use across multiple enterprises when equipment is shared; what is the best way to split costs for use and maintenance?

- For small tools that are shared (like weedwhackers), what happens if something breaks and who oversees repairs?

- Identifying which equipment is not available for use by farmers

- For large equipment, like tractors, deciding who is responsible for the maintenance and large repairs.

Equity and Exchange: Deciding what is a fair and practical exchange for access to land and other infrastructure. Examples include the exchange of money, labor, or farm products for use of:

- Structures for office, equipment storage, processing, and product storage.

- Equipment usage—including tractors, greenhouses, fencing, and small tools.

- Land

Examples of other discussions include clarifying a process for rent increases over the term of the lease; clarifying whether farmers can sublet to other farmers to contribute to rental fees; and formulating a fair way to split up utility costs when utilities are shared.

In one case, farmers were washing and packing in a building that needed renovations to meet the landowner’s need for safety and stewardship of the property. While the farmers used the space, they could not afford to make any structural repairs to the building. Conversations occurred that clarified expectations for the space, future use, and responsibility for capital investments. Participants were able to arrive at a “value” by determining what farmers would opt for if they could not access this building. This helped to establish a “farm value”.

The difference between the value of repairs or capital projects to a farmer’s operation, versus the value of repairs from a landowner’s stewardship or aesthetic goals, came up in multiple groups. Arriving at the value of something, according to the farmers, and the question of fair and responsible expectations was complicated by spaces being used or valued for multiple purposes.

Communication: Determining how to achieve an effective communication process.

- Multiple groups discussed how their process was mostly informal and how they would benefit from a more formal process, going forward.

- Farmers expressed gratitude for communication with landowners based on mutual respect.

- Farmers expressed wanting the opportunity to clarify expectations through consistent communication.

- Multiple groups agreed to review their lease annually, in the spring, and to schedule several check-ins over the course of the year.

- Multiple groups discussed who needed to be at various meetings, when it makes sense for a small group conversation, and when it makes sense for the whole group to meet.

- Farmers agreed to submit an annual plan each year, to the landowner, and to have consistent quarterly meetings.

Multiple Enterprises Sharing the Same Farm Property: All the farms had a landowner who lived on the farm property or close to the farm operation. Three farms had farmers living in residential rentals on the property. Two farms had farmworkers living on the property. One farm did not include any residential farm lease. Examples of issues discussed include:

- Placement of compost piles

- CSA distribution sites

- Events—planning around on-farm public access

- Visual issues—keeping the viewshed open for guests on the property

- On-farm worker housing and how this impacts landowner

- Discussion around adding working pets—farmers wanting to add a dog for the farm or a cat for the greenhouses

Three different landowner groups all ran their businesses on the same farm property: a retreat center, a glamping business, and another agricultural enterprise. A fourth landowner was very involved in nature conservation efforts and had developed public trails on the property. A theme here was around integrating business efforts to enhance “mutuality” by collaborating in ways where each business was positively influencing the other. In three groups, landowners saw their farming partners as adding value to their business efforts.

Multiple Tenants: Three of the farms had relationships with at least one other farming tenant, who shared the land beside the farm participating in our mediation session. In one case, a biochar operation was operating on the farm property. In another, a livestock farmer rented pastures for grazing. In the third, fields were leased for haying. Discussions focused on coordinating overlapping uses. Other discussion topics included:

- Farmers who were hoping to gain access, over time, to more ground

- Restrictions for land use when two businesses need the same ground

Stewardship Responsibilities: This relates to the actions of stewardship and to who is going to perform those actions. What are some strategies to meet stewardship goals, for both the landowner and the farmer?

- Discussions around roles and timelines for action items

Information Exchange: Groups shared any changes made to business plans and operations. They also detailed personal life changes. Examples of personal changes shared:

- One farm had hosted a farmer’s wedding and two farmers were expecting new babies, so they shared information about the celebration and discussed the implications of these changes.

- Landowners shared information on job changes and retirement shifts, as well as their intentions about downsizing to a house off-property.

Examples of information sharing about business issues:

- Two farms shared details about ownership changes, each having bought out a third partner.

- Farmers shared changes to business plans, for expanding their operations and making them more viable.

- Farmers updated landowners on changing and evolving business plans and shared the financial details of the operation.

Tenure Issues: Security & Access

Security means that the farm operator lives relatively free from the fear that they will be arbitrarily kicked off the land, or that the terms of use will be altered without due process. It also means that the length of the lease agreement is sufficient for the farmer to meet their goals. Examples of issues discussed around security:

- One group had a ten-year lease in place that would expire in a few years. The landowners were trying to move the land into a conservation easement, but farmers had concerns about the impact this would have on their business. Landowners did not have enough information at this “work in progress”

- Farmers wanting to find out more about the landowner’s long-term plans for the property.

- Farmers wondering about the possibility of putting an OPAV on the property to potentially make the land more affordable for the farmer to purchase from the landowner.

- Farmers hoping to extend a lease from 2-years to a longer timeframe.

- Farmers wanting to know what might be possible in terms of a long-term solution, such as a 99-year lease or simply buying the farm.

- One farm needed a longer lease to be able to apply for NRCS grants which would, consequently, increase the viability of their operation.

Access addresses the user’s rights to access and control the land sufficiently to meet their farming goals. If a farmer owns the land, they enjoy maximum rights and control. Whereas tenancy offers a farmer access to the property, subject to the conditions outlined in their agreement. Most of the access discussions were around the possibility of negotiating access to more acreage or to building infrastructure for the farmer’s expanding business.

Interpersonal Issues: This relates to clearing up tensions between the landowners and farmers. Examples of issues discussed include:

- Sharing information around a conflict the landowner had with a neighbor. Discussing expectations and figuring out what works so that farmers don’t feel like they are “walking on eggshells”.

- A discussion around who will be a part of the farm operation, as it evolves, and how that will be navigated over time.

- Clearing up tensions with a third-party regarding their relationship to the land and to borrowed equipment.

- Landowners seeking to gain a greater social connection with the farmers.

Exit Strategies: What happens if the farmers stop farming? How does the current relationship end if either party wants out? Examples of issues discussed include:

- How do farmers leave the land? Should former pastures be reseeded?

- What happens to the house lease if the farmers stop using the land? Would there be a set time in which the farmers would need to move out of the house?

- One group realized that their arrangement could provide neither the farmers nor the landowners with what they needed financially. This group worked on timelines for shutting down the farm and on strategies for preserving relationships during the closing process, including communication on how best to share their decision with the community.

Part Three: Outcomes by Farm

Descriptions of each farmer/landowner group includes this fundamental information:

- Description of the farm operation

- How long the business has been in a lease arrangement

- Landowner’s background and relationship to the property, including if they operate a business on the same location, and whether they live on the property.

- Whether farmer lives on the farm, and other enterprises that lease the farm.

Apis Apotheca

Aviva Skye has been running Apis Apotheca for two years as sole proprietor. At the time of the mediation session, she was in the middle of her first season growing at Gatherwild. Apis Apotheca grows products primarily for their line of herbal skincare products, which are sold online, in shops, and at farmer’s markets alongside fresh herbal offerings.

Skye connected to landowner Laura Sink through a mutual friend. She had learned about the opportunity through an ad on Craigslist, where Sink had posted that she was looking for someone to farm her land and had included a farmhouse rental in the offering.

Sink runs a Glamping Business called Gatherwild, which offers rental yurts and stays through Airbnb, and of which she is the innkeeper. She has been in business for about two years and sees the active use of land by a farmer as an added benefit and a draw for her hospitality business.

Their lease agreement was informal and considered an agreement between friends.

Mediator Statement: The intake session was critical for the farmer and helped her to get clear and organize her thoughts. For both parties, the intake session included questions on where they were coming from and where they were going.

Outcomes:

For this session, several short-term issues were addressed. Prior to the mediation session, rent had been paid through hourly labor exchange, but the farmer felt this was difficult to provide when her own business was so labor intensive. The farmer researched going rates and came up with a proposal to which the landowner agreed.

The use of tools and shared equipment was another topic that was reviewed as some clarification was needed. Landscaping issues around the farm being used for different purposes—both for hospitality and production—were also discussed.

In terms of interpersonal issues, and with a new baby in the picture, separating Sink’s dwelling place from the farm’s activities was an important change to discuss.

The discussion around long-term issues included infrastructure for the future, if the farm were to stay and grow—such as irrigation, since a well would need to be added to the farmstead—along with the possibility of investment in shared tools. They also discussed integrating business efforts and collaborating in ways so that each operation was positively influencing the other.

This farmer/landowner group felt that one session got them to where they wanted to be, and they did not need to use the full pilot set of four sessions.

UPDATE: Skye is currently fully employed with her business Apis Apotheca. She relocated her business and gardens to “a perfect little homestead” in Elizaville, NY.

Ironwood Farm

At the time of the mediation sessions, Ironwood Farm had been in business for a few years. The farm grows certified organic vegetables and herbs on seven acres in Ghent, NY. They also sell produce at farmer’s markets, sell CSA shares, and sell wholesale to restaurants and resellers across the Hudson Valley.

They are co-owned and operated by Jenny Parker, Lauren Jones, and Aliyah Brandt. Over the course of this pilot, they restructured with Jones and Brandt buying out Parker, as she left the partnership to pursue a farming opportunity in Idaho. 2019 will be the first year where Jones and Brandt are co-owners.

Ironwood Farm leases about 8.5-acres tillable, plus creek access for irrigation, a greenhouse site, and parking and storage areas, from the Tipple family, who have strong roots in the local community and are part of a multi-generational farming family. The family used to operate a grain business and relatives still operate a farm equipment business adjacent to the property. Dave Tipple is also a minister at the local church.

After looking at several land lease offers, Ironwood Farm chose to work with the Tipple family, beginning their operation on the land that sits right across the road from the Tipple farmhouse and adjacent to their barn.

The farmers do not rent any residential housing from the Tipples—they live in adjacent towns. The Tipples use the adjacent barn for both equipment storage and for housing their horses. Ironwood Farm has repaired a small outbuilding to use for storage and as a pack shed.

Mediator Statement: Normalizing tension and differences, continuous routine review, and a trajectory were important for this group. Given regular meetings and the opportunity to clear up tension, the group felt like they were in more of a partnership. The structure and focus were also useful, which encompasses things like deciding what to talk about, meeting preparation, and making the time to meet.

Outcomes:

Interpersonal issues around transition were a theme for this group, as farmers went through an ownership transition and co-owner partners also went through personal family changes, such as marriage and each family having babies. The landowner couple was also adjusting to job transitions and to retirement.

Farmers and landowners clarified the process around issues with infrastructure, sorting out repairs to a well, road access, and drainage issues—including the responsibilities for costs, labor, and timeframes. This group also reviewed and adjusted timelines and expectations around existing agreements for infrastructure use and improvement, sharing achievements and their hopes for the next steps.

Farm partners addressed tenure questions for long-term security, and landowners clarified their intention for the land to remain in farming but also said that their children would have to decide what they wanted to do, when they passed the land along.

Discussing a neighbor relationship helped to clear tensions and clarify expectations.

Rock Steady Farm & Flowers

Rock Steady Farm & Flowers is a woman and queer-owned cooperative farm, rooted in social justice and growing specialty-cut flowers and sustainable vegetables in Millerton, NY. D. Rooney, Maggie Cheney, and Angela DeFelice co-owned and founded Rock Steady but, during the timeframe of the mediations, DeFelice transitioned from a co-owner/operator to a remote consultant.

Rock Steady is a cooperatively owned farm, offering opportunities for equity to staff members after a trial period. The farm shares land with, and feeds the kitchen of, The Watershed Center, a social justice retreat and resource center for changemakers.

The Watershed Center offers seminars, workshops, consulting, and organizational retreats. Brooke Lehman and Gregg Osofsky own the land, are founding members, and are on staff at The Watershed Center. Gregg Osofsky has strong roots in the local farming community with his family being in the dairy business. Rock Steady came to the land after a flower grower who leased there had relocated. This is the second farmer lease relationship for the landowners.

During these mediation sessions, the farm experienced a challenging weather event when a microburst touched down on the farm, collapsing their office structure. In addition to the office being ruined, one co-owner suffered a concussion and experienced some health challenges associated with healing.

Mediator Statement: This group came away with a renewed appreciation for the challenges they were each facing and the thinking that went into decision-making. They were able to address some challenges around water and the ridge field, which had created a rift in trust, and did some overall repairing of their relationship. While they did not come up with answers to security questions nor to long-term tenure, talking about tenure and sharing their concerns and intentions helped to create a partnership and a sense of security around being able to work things out in the present.

Outcomes:

This farmer/landowner group has a high level of overlap, due to physical proximity and shared land, as well as ideological overlap between multiple enterprise visions and missions. Two farmers and the landowners live on the property, in proximity to one another. In addition, the land hosts two businesses—Rock Steady the farm and Watershed the retreat center—which share a tight footprint. This group’s sessions required a good deal of sorting things out and created clarity.

Roles, entities, and key relationships in decision-making were clarified. Discussions occurred around the businesses sharing ideological purpose and alignment—collaborating in ways where each positively influences the other.

Stewardship issues were discussed for the landscape, used for different purposes by two separate operations, with questions on how best to integrate things and decisions about different uses for the property.

The group discussed infrastructure improvements and who pays for what, though not everything was resolved. Infrastructure issues around capital investments, versus farm business investments, were also discussed.

The tension around a season that included drought and water shortages, affecting a shared pond for farm irrigation and a swimming hole for retreat center guests, was explored, and a plan was put into place for future drought seasons.

Both groups—landowners and farmers—had concerns about long-term tenure and security. Rock Steady had a rolling ten-year lease in place and were in their second year with the lease. Landowners were trying to move the property into an easement and were gathering info, by learning and mapping out details. Farmers had concerns about how these changes might impact their business, but landowners were unsure at the time as everything was still a work in progress.

Since the landowners of this group also have a business on the same property, they also had concerns about tenure. The landowners wondered about agreements that they had made with this cooperative farm team now affecting them, as the cooperative owners might change and evolve. What input did they have regarding business ownership, as members transition in and out? They discussed security and tenure in all its complexity and how that would get navigated.

This group will continue to work on their written lease agreements together and look for solutions—including legal advice and tenure models—to achieve long-term security. Their evaluations specified the need for more help navigating the issues that surfaced, and content expertise around leasing options and language.

Short Creek Farm

Short Creek Farm was founded in Northwood, New Hampshire in June 2015 by friends Jeff Backer and Dave Viola. The farm operation is situated on 200-acres of field and forest. The farm produces pastured pork, grass-fed beef, and heirloom vegetables in an ecologically conscientious manner.

Landowner Carl Wallman established Harmony Hill Farm on the land that Short Creek Farm leases in 1969, and he lived there and raised cattle until 1994. Even after Carl moved off the farm, he continued to keep an office in the farmhouse and grew a garden there for family use. Carl was a conservation-minded pioneer who put the land into several conservation easements foreseeing that, in the future, this larger parcel of land might need to be farmed by multiple operators, so he wanted future farmers to have the ability to acquire portions of the land. Carl had a deep appreciation for the natural world, was a steward of the land, and believed that the land should be accessible to the community. He was one of the founding members of the Northwood Area Land Management Collaborative (NALMC), whose mission was very much in alignment with his belief system.

Before coming to Northwood, Jeff started Potter Hill Farm, in Grafton, Massachusetts, where he grew a wide variety of heirloom vegetables and flint corn and raised pork and beef on pasture. Over five seasons, both he and Potter Hill Farm became fixtures in the lives of many families in the community. Jeff brings that same ecologically rooted agricultural management that he practiced at Potter Hill Farm to Short Creek Farm, with the goal of improving the quality of the farmland while at the same time producing nourishing foods from it.

Dave has had a hand in progressive food companies throughout New England; notably, he developed well-respected charcuterie programs at Farmstead in Providence, Rhode Island, and Moody’s Delicatessen and New England Charcuterie in Waltham, Massachusetts. Dave recognized the need for farmers to be able to turn their goods into high-quality finished products. This is Dave's role at Short Creek—taking the incredible meats and vegetables grown on the farm, making them last longer, and making it easier for you to turn them into a delicious meal at home.

Carl had a long-standing and separate handshake arrangement with another farmer, Tony Matras, to hay some of the fields included in Short Creek Farm’s lease. Tony hayed the land free of charge in exchange for building the fields’ soil health and maintaining the hedgerows around each of the fields. The landowner wanted Jeff and Dave to work with Tony to figure out how both farm businesses could work together, and to figure out how best to allow each to utilize the fields, so that both the land and their separate businesses would benefit.

Mediator Statement: The farmers wanted to develop longer-term security for the farming operation, and the first step was to move from a 2-year rolling lease to a 5-year lease. The farmers also wanted to understand the landowner’s long-term plan for the land as the farmers had an interest in purchasing it (if possible). Furthermore, the farmers wanted to gain more control over decision-making around how to utilize the fields included in their lease, and this involved figuring out how best to share the fields with a hay producer, who had a long-standing handshake agreement with the landowner. The landowner valued community connection and wanted the leased property to be accessible and welcoming to both the immediate NALMAC community, as well as the greater Northwood community. He had concerns about whether his farmer tenants shared those same values. At the start of the pilot program, the landowner had not yet developed clarity on what his vision was for the future of the farm and, therefore, was not sure what he was willing to commit to in terms of offering the farmers long-term security in their lease.

Outcomes:

The farmers were able to establish a 5-year lease with the landowner, in which they could utilize more of the fields and have greater decision-making power around how best to use the land for their farming enterprises.

Part of Carl’s decision to extend the length of the lease was based on previous conversations with the farmers, around his values of stewardship of the land, and the importance of the land being connected to the community. Carl’s early reservations about extending the lease were due to his not being certain that the farmers shared these values. As a result of addressing this concern during mediation, Jeff chose to join Carl at some of the NALMC meetings and, eventually, became a member of the NALMC Steering Committee.

In the final mediation session, after completely reviewing the lease, the conversation turned to long-term security for Jeff and David. Topics such as building their farming business; investing in infrastructure; and planting firmer roots in the community were all discussed. The farmers also discussed their goal of building a farming business that would allow them to make a reasonable living wage and build equity on the land. Furthermore, they have a short-term business goal to build a barn that houses livestock, for the animal’s welfare during the winter months. To build Class A improvements, though, they needed a lease with enough time to recapture the cost of their investment.

At the time of the mediation sessions, Carl was not yet ready to discuss increasing the length of the lease beyond five years. He expressed his desire to revisit this conversation towards the end of 2018, or in early 2019. In the meantime, Jeff and David will think about how long and what type of lease could offer them the security they need for their farming business goals.

Another point of discussion was the possibility of whether a Land Trust placing an OPAV on the property would make the farm affordable enough for Jeff and David to purchase. The Forest Society, which holds the conservation easements on the property, is not interested in pursuing holding OPAVs. The Southeast Land Trust is looking into whether this is something they want to pursue, and they may be interested in holding the OPAV on Carl’s farm property.

UPDATE: Before Carl’s passing, he made the decision to donate the farm property to the Southeast Land Trust (SELT) on the condition that they amend the conservation easements, including OPAV language, and then offer the property for sale to Jeff and Dave. The money from the sale of the property will be used to start a fund at SELT to facilitate more OPAV projects.

Jeff and Dave are currently in the process of purchasing fifty acres of the farm, including the house, and will be leasing the rest from SELT with an option to buy in the future. The closing is expected to be within the next several weeks.

Jeff reflected during a follow up conversation, “It's clear to me that Carl was thinking of our continued success here, towards the end of his life. I was touched by his generosity in thinking about us, in addition to thinking about the fate of the farm itself. I'm sure that the dialogue started during our mediation sessions contributed to this outcome—our security on the land and then Carl's peace at the end, in knowing that we would try our absolute best to be good stewards of his beloved farm”.

Sullivan Center for Sustainable Agriculture

Description of Farmers and Landowners:

The Sullivan Center for Sustainable Agriculture (SCSA) was established by Carol and Steve Sullivan and Rich Sullivan in 2011, after all three had retired from their former careers. SCSA is comprised of Angel Wing Farm—owned by Carol and Steve Sullivan, which produces a variety of organic vegetables and fruit—; a BioChar business owned and operated by Rich Sullivan; and an educational center in its developmental phase. In 2016, SCSA began to think about who the next generation of farmers would be, to take over the different enterprises, and placed an ad out looking for successors.

In 2017, SCSA established a one-year MOU agreement with farmer Laurel Schultheis Witri and her husband Micah Witri. The MOU agreement was to be for Laurel’s first year as a startup and included a rental house (free of charge for the first year, owned by Rich Sullivan, and situated adjacent to the farm property), along with all the gross sales Laurel made from Carol and Steve’s Angel Wing Farm vegetable and fruit business. Laurel and Micah also had the opportunity to take over Rich’s biochar operation and earn some additional income through it.

Carol and Steve have a separate home on the property, located near the farm’s greenhouses, farm stand, and garage. For the first year, Carol and Steve worked alongside Laurel in the vegetable operation to mentor her on how they had been running Angel Wing Farm, in terms of both production and marketing. They also shared the farm’s financial records with Laurel, so that she could become familiar with the numbers and cover all the farm’s expenses for the first trial year. Micah had an off-farm job and helped with maintenance-type tasks, as time permitted, along with occasionally helping in the garden. Rich lived off the farm and was supportive of bringing along Laurel and Micah as successors but was not as involved in the day-to-day business of SCSA.

Laurel learned of the pilot mediation program and reached out for some guidance around planning how to transition from the current MOU agreement to a more detailed and longer-term lease agreement. The hope amongst all parties was for Laurel and Micah to take over Angel Wing Farm’s business fully, and then pay to lease the farm property and rent Rich’s house in the second year. There was also discussion and some effort made around Laurel and Micah taking over and eventually buying Rich’s biochar operation.

At the time of the mediations, Laurel and Micah were in the second half of their first year on the farm. All parties were open to having mediated discussions around developing a lease agreement for the farm operation; a separate lease for Rich’s house; and perhaps a third lease for taking over the biochar operation.

Mediator Statement: The MOU agreement served as a source for many implicit assumptions around short-and long-term expectations, for both the landowners and the farmers, and the mediation sessions allowed people to explicitly discuss what they hoped for, needed, and what was not an option. Key themes for this group were around communication, maintenance, and stewardship of the property—sharing resources, labor, developing boundaries, and detailing how the transition into the second year, and beyond, might look.

Outcome:

As part of the information gathering and business planning process, it was identified in the first mediation session that it would be beneficial for Laurel to take UNH Extension’s business planning class for agricultural producers, which she did. She then went on to work with a business consultant at Hannah Grimes Center, to further develop her business plan and to focus on how to make the farm a financially viable endeavor. All parties worked throughout the mediation period, exchanging financial information, and clarifying business, labor, and personal needs. Carol, Steve, and Rich also gained clarity around their needs, in terms of a successor for SCSA.

Improving communication was a priority for the group, in relation to the farm itself and to shifts in responsibilities, as Laurel and Micah switched from a trial period and towards establishing leases and taking over existing businesses. This group agreed to regular, formalized meetings; to discussing options; and to making decisions in between the mediation sessions.

The final mediation session occurred during late summer of Laurel and Micah’s second year on the farm. The group had collectively concluded that the MOU agreement could not continue beyond the current season and that, ultimately, their long-term goals did not align. They shifted focus towards determining a timeline for shutting down the current configuration of the farm operation. Though the outcome was disappointing to all parties, their intention was to preserve relationships, keep communication open, and to part on good terms.

Update: In 2019, Rich Sullivan sold his home adjacent to the farm. As a result, Angel Wing Farm lost some of their vegetable growing area. Steve and Carol Sullivan also closed Angel Wing Farm’s farm stand for 2019, to concentrate on bringing the garden spaces back to health. In 2020, they opened the farm stand back up but, due to Covid-19, had to shift to online ordering and curbside pickup. For help with the farm work, they developed a "work-for-shares" program, where hours were credited at an hourly rate in exchange for payment in produce. This worked well for everybody and is a program that they plan to continue. Steve reports that, at some point, he and Carol will revisit finding a successor but, for now, they are enjoying farming. Steve also shared that the process of the four mediation sessions, and additional resources shared through Land for Good, resulted in him and Carol feeling much more prepared to start the succession planning process in the future.

Part Four: Discussion and Findings

Methods: One change has been made from our initial description of the mediation process. All five cases included an initial pre-mediation session, before the farmer/landowner groups had their first session. In those sessions, mediators met with the farmer(s) and landowner(s), separately, to hear their concerns and gather notes about any issues they might like to address over the course of their meetings. Participants were also sent a farmer or landowner questionnaire, to help them clarify their thoughts and to guide the pre-mediation sessions. Mediators went through each question on the worksheet and listened to any other concerns. Through this process, mediators were able to learn about the farmer’s and the landowner’s history, in advance, and gained understanding of the participant’s unique context.

Notes on Mediation Style—NH groups and NY groups:

For this project, we had two mediators working in different states. One mediator used the facilitative style of mediation and the other the transformative. Many mediators are trained in both styles and use a combination, depending on the case and the parties being mediated, as well as their own preferred approach.

Differences in approach are highlighted below. Impacts on the different approaches, for the cases, are addressed later in the report.

New Hampshire: Facilitative Mediation

Cara Cargill is a mediator for New Hampshire Agricultural Mediation Program and works as the New Hampshire Field Agent at Land for Good. She practices the “facilitative” model of mediation. In addition to being a mediator, she is also a “content” expert and works with farmers on issues of farmland access, tenure, and farm transition. After mediation sessions were complete, she put on her advisor hat to guide the parties towards resources and gave them things to consider between sessions. In this sense, Cara’s role was a bit more directive than most facilitative mediations would be, as there’s not usually a content expert also acting in the role of mediator. She was able to transparently share when that role changed, from facilitator to advisor, throughout the sessions and with the groups.

In facilitative mediation, the mediator helps parties to set an agenda and outlines a process that will assist the parties in exploring their concerns. The mediator identifies and seeks to understand each parties' point of view, and then searches for underlying context beneath the positions taken. The mediator will ask open-ended questions, to gain clarity and make the implicit explicit and will assist the parties in exploring and analyzing options before tracking and drafting agreements and decisions.

New York: Transformative Mediation

Claudia Abbott-Barish is a mediator practicing the Transformative Mediation Model, for a Community Mediation Center following that model. She has roots in the farm community of the Hudson Valley, and experience with farmers leasing land, but would not be considered a “content expert” and does not work in farm advocacy.

With the Transformative Mediation Model, a mediator supports the continuous process of a party’s decision-making—including decisions about how the process is structured; topics for discussion; and potential options and outcomes.

Mediators follow and reflect on the participants’ conversation, giving them the opportunity to edit their own remarks. The mediator also asks questions for clarification—not open-ended questions—with the intention of helping the parties to reflect. Mediators listen and follow the developing themes, responding to any opportunities that arise in that conversation, with comments that allow parties to gain clarity and make their own choices. Mediators also consider, acknowledge, and respond to the perspective of the other party.

Mediators summarize areas of agreement and disagreement, being careful not to lead the parties in any direction. Mediators also track and draft agreements and decisions.

Mediation Process: Farmers and landowners found the process valuable

Landowner and farmer statements about the value of the process:

“The formal framework of having a mediator was ‘very helpful’. I think other farmers in lease arrangements would find working with a mediator useful. It was very comfortable.” – Farmer

“Having people present in our conversation brought a greater integrity to the process. The mediator brought a level of listening and care that informed the nature of the dialogue and made the conversation generative.” – Landowner

“We addressed the basic communication and relationship challenges that we had been struggling with. We created a supportive ground on which to deepen our work together.” – Landowner

“Working in this way was healing in a sense and made a big difference in our ability to honor and respect each other’s perspective.” – Landowner

“I think just having someone in the room was the most helpful. It changes the dynamics—shifts the dynamic because we know we (or the group) will be supported if it gets hard. It pushes us out of some of our patterns of communication.” – Farmer

“It created a safer space to talk about contentious issues. At the most basic level, having someone present continually reminds us of our goals for communication and interaction, which we aspire to. It was also helpful to have someone reflect to us their needs, goals, and observations as we worked through murky stuff.” – Farmer

“By session three, I felt more comfortable bringing up issues in a more direct manner. It took a few sessions to break out of our old communication patterns and trust that we could be honest without it escalating.” – Farmer

“The mediator has the knowledge, communication skills, and demeanor to be able to help work through any differences between parties.” – Landowner

“The mediation session was helpful for “focusing” the conversation. Having someone there to direct the conversation helped us to have a conversation different than the one we would have as friends.” – Farmer

Making Sense of the Themes:

Four themes that showed up across all five farms in sessions:

- Stewardship

- Infrastructure Issues

- Equity and Exchange

- Communication

Since mediators did not lead conversations but rather facilitated the groups, towards creating agendas and topics, we can assume that these might be some common themes ripe for discussion in a lease situation.

Infrastructure issues were a starting point for most groups, with the need to clarify options and responsibilities, and to do some collective problem-solving when improvements were necessary. Infrastructure issues were concrete and observable—not based on opinions, beliefs, or values.

The other issues were more relational.

Stewardship issues were raised from a values or vision perspective with landowners and farmers conversing to gain understanding of each other’s needs and reasoning. Stewardship also got discussed on four farms, within the context of who is responsible for what—i.e., the doing part of stewardship.

Equity and exchange were discussed around ideas of generosity and flow, as well as determining what is “fair”.

Communication became something that groups planned together.

These themes showed up across four farms in sessions:

- Community Relationships

- Multiple Enterprises

- Multiple Tenants

- Stewardship Responsibilities

- Information-Sharing

- Tenure

Multiple enterprises and multiple tenants were situational and context specific.

Stewardship responsibilities included sorting and clarity around expectations.

Information sharing about business issues would be obvious, as businesses went through changes and evolved over the seasons.

Community relationships and how the farm functions, as part of a larger whole, were issues discussed across four farms. This could be a topic worth highlighting—it is related to the issues discussed, landing mostly outside of formal lease agreements. Being part of a place is experiential and is shared by the landowner and farmer. Individuals also navigated issues of public versus private space in a location, as well as the neighbor’s relationship to both the farm, the land, and the individuals—all which can affect quality of life.

As farms start to have viable businesses, and their focus shifts from year-to-year to the longer-term, getting clarity about the longer-term possibilities becomes a real concern for farmers. Four of the farms in this study had tenure concerns.

Making sense of the data not emphasized in the themes section:

It is helpful to understand the impact of the relationship between the landowner and farmer. In this small study, a substantial overlap between farmer and landowner, such as a shared residential footprint, or multiple tenants on the land—may indicate higher communication needs. Developing a substantial and structured communication plan may be a useful addition to a lease agreement. Also, it is advisable to plan for tension and expect it to occur, with a plan for getting help and talking through the tension with a mediation specialist. Anything that can be done to “normalize” the conflicts of interest and any needs that may arise could make the discussions much easier.

Answering “yes” to any of the following questions may indicate a relationship with high impact:

- Do farmer and landowner share a daily overlap on the land?

- Are both farmers (or farm workers) and landowners living on the land?

- Are there multiple enterprises on the land, with overlapping resource-sharing?

- Do farmer and landowner operate synergistic enterprises?

- Is the landowner an investor or partner in the farmer’s business?

The Who of the Farm Enterprise:

During the timeframe of this pilot, one farm went through a partnership/owner change and one farmer had a breakup with a farming partner, which shifted the business scope and goals. For the cooperatively structured enterprise, intentions existed to bring new worker owners aboard the business in the future, and one worker owner shifted to a remote consultancy status.

This may be indicative of some changes that happen early on in establishing an agricultural business on leased land, though this sample is too small to draw that conclusion.

This raises questions around what needs to happen when the “who” shifts in a business lease arrangement, from a landowner’s perspective. Do agreements shift in any way? What is the impact to a lease agreement if there is a change in business ownership?

The role of stress in startup-farming & multiple stressors pileup

Farming is a stressful and risky business, across all farming sectors. It is physically demanding and the learning curve when working in a complex natural system is steep. Startup farming is enormously capital intensive, as well, and production is weather dependent. Adverse growing conditions can stress even the most experienced of farmers. Also, the tight profit-margins of farming, the seasonal push, and the physical intensity of the work all combine to create a situation ripe for stress—and, when folks are stressed, they may not have the bandwidth to attend to relational tensions, which have a bigger impact when added to the stress of starting a new farming operation.

According to Mike Rossman, an expert on farm behavioral health and farm stress, “The worst threats to farming operations are financial insecurity; others include unpredictable events such as bad weather, disease outbreaks, personal health issues, market shifts, and other factors beyond our personal control. Most people can handle two stressors simultaneously, but three are usually beyond our capacity.”

All the farmers in this study were in startup mode: Ironwood and Rock Steady were advancing towards a stable market and production in their farm enterprises. Apis Apotheca was in year-one of production and in their second year as a skincare product line; Short Creek Farm was in year-two of a new enterprise; SCSA was in their second year on the land and were working out the details for the business to become their own.

Transitions: Any life transition can act as an additional stressor, as individuals adjust to the changes. There were changes that some of the farmers and landowners were going through, over the duration of this project, which did not relate to the lease relationship. Such as:

- Marriages and new babies

- Retirements

- Unexpected health issues

- Business partnership changes

- Relationship breakups

- Household relocations

Lease and Farm Transition:

In one of the groups, a lease arrangement was also part of a farm transition—with farmers retiring (downsizing) and bringing new farmers on as successors, with a lease arrangement that included land, housing, and access to infrastructure and equipment. Bringing on a new farming operation, retirement, and succession issues included many transitional layers, from both the landowner’s and the new business owner’s perspectives. Both sets have financial mapping and planning to work through, and additional financial consultation could be important for both farming groups, to create a farm transition with a clear understanding of the financial needs associated. A structured communication plan is indicated.

Other Topics:

The one-size-fits-all approach of this pilot:

The one-size-fits-all approach that we initially laid out for the pilot proved to be ineffective. The initial proposal involved each landowner/farmer group using four sessions over the course of a year. Three of the groups did use the four sessions, but in a timeframe longer than the initial year proposed. One of these would have liked additional ongoing support:

“We need more support over a longer period of time.” —Farmer

One group used three sessions, spanning well past the year goal, and was navigating a farm business partnership change, a marriage, and each owner adding a new baby to their separate families.

A fifth group used only one session and was satisfied with what they were able to accomplish. They did not feel the need for additional sessions.

Conclusions point to an effective lease mediation process being customizable to meet the group’s needs, with a mediator being drawn in over time, as the relationships and startup businesses evolve.

Notes About Content Expertise:

The two New Hampshire groups were able to draw on the mediator as a content advisor, when appropriate. Two of the New York groups relied on the communication expertise of the mediator and did not need the advice of a content specialist. The Rock Steady group really needed some content expertise, though, due to complex and complicated overlaps—especially related to potential tenure models. Their comments below point to this:

“We decided that we need more support in this work, possibly someone with legal and farm expertise to help us navigate some of the technical aspects of the agreement.” — Farmer

“I think I anticipated more active involvement on behalf of the mediator(s). Helping to push us towards clarity and making decisions. It felt very passive (which was fine) but also curious if a model of increased involvement, and more guidance, would have allowed us to get further in the conversations. More sessions are needed to really navigate a lease and all its components, especially when a relationship is as complicated as ours. — Farmer

I feel that this form of mediation is a good starting point for working through a lease but requires an additional component that creates space to formalize things, in a written agreement, and better understands legal implications and norms. —Landowner

This would suggest that a mediator should assess the needs of the group during an intake process and be able to refer groups to, or collaborate with, content experts in an advisory role, when needed—for information gathering and education on lease possibilities and structures. When content expertise is part of what the group needs, an integrated process would be beneficial for the farmer/landowner partnerships.

Part Five: Conclusion and Recommendations for Further Study

This pilot involved five startup farms in lease arrangements. As a pilot, this is not a large enough sample to draw conclusions on the benefits of agricultural lease mediation, at least for this population. In addition, since it focused on beginner farm operators, no conclusions can be drawn for the use of mediation for farmers who are in different phases of their careers than this study. However, some of the themes and issues that surfaced, across farms, normalize some of the kinds of tensions that landowner and farmer leases may experience. In fact, the normalization of tensions and the need to communicate is a positive outcome of this research.

Tenure is an area that still needs development— attention needs to go towards developing models and materials for different types of tenure arrangements.

While many of the topics that got mediated were things that a lease details, some were not and were relationship-based or interpersonal.

With business growth and the need for expansion, the infrastructure that a business starts with may not be what they need once they get to the point where they have a viable business with steady and stable markets. In this sense, a lease needs to remain flexible as the business evolves through a startup phase—meaning the leasehold conversation may be viewed as ongoing, at least in the early years of establishing a business.

Another recommendation is that services be available for startup farmers and that they remain free. With all the financial risks associated with farming—startup farming, in particular—most farmers would not be able to prioritize funding the expertise of a communication specialist.

“It would be great if there was funding available for ongoing support, as it would be hard to put mediation into our budget as a new farm.” — Farmer

Over the course of this SARE Pilot Grant, the Agricultural Mediation Programs that exist in forty-one states were granted case expansion in the 2018 Farm Bill. These programs now offer lease mediation to farm communities for free.

Farmers, landowners, and other agricultural service providers may not know about this completely free new service. Learning how to integrate agricultural mediation with existing programs like Land Links, Farm Transition Programs, and Agricultural Business Consultants, who work with startup operations—as well as other programs focused on land access—will all be necessary if mediation is to become a tool that a farmer and/or landowner can draw on, thereby creating a positive partnership within their lease arrangement.

Integrating lease mediation into an already-existing array of services for the farm community deserves more thought and attention. Participants, both farmers and landowners, were enthusiastic about participating in a mediation pilot study and it was not hard to find five farms that were willing to participate. At the beginning of this SARE Grant, lease mediation was a new concept. None of these farms were specifically seeking mediation though all found it valuable.

Recommendation for Further Study:

While the benefits of mediation for this small sample are only anecdotal, in nature, a recommendation for further study would be to research a larger sample of cases—exploring and articulating the benefits of mediation-applied lease situations. A larger research project might focus on the beginning farmer using a lease situation to access land for a startup but might also include other uses of lease land—for example, as a strategy for farm expansion when an operation needs to grow beyond its home farm borders.

In addition, there has not yet been research into the cost of a failed lease arrangement, such as when conflicts lead to the farmer choosing to leave, or to the landowner deciding not to continue. How does a failed lease impact a new farmer’s career trajectory, and how costly is lost land to a farm that relies on leased ground?

One further area of study, which may become important over the next decade, is using the farm lease arrangement as a trial for a farm succession, with one farmer retiring and another non-family member/new farmer coming onto the land, and into the farm business, as a leased or tenant farmer. This is a situation that gives both parties an opportunity to examine the possibilities for business and, in some cases, land transfer. Extra support may be needed for the unique needs of both the retiring farmer and new farmer, as well as help navigating the possible transition from tenant to owner of the business and land, in the future. Very careful communication and working agreements need to be utilized because of the levels of complexity around financial needs, for both the beginning and retiring farmers, as well as any life transitions and identity shifts that may occur during the transition.

Research Results

Previous to this pilot, NYSAMP mediated leases when there is a crisis or breakdown in farmer landowner relations. When both parties are willing to come to the table mediation has a high success rate.

This project offered mediation for maintaining communication rather than for addressing a crisis, to farmers and landowners. A mediator’s skill was used proactively to help parties discuss complex substantive issues. Mediators helped define issues, emphasize common goals, keep conversations focused, facilitate the development of discussion and of options.

This project seeks to discover if proactive lease mediation could be an effective support system for farmers and landowners and to gage the value of using mediation at the front end of a relationship.

Farmers and Landowners reported that the process was valuable. In addition case studies allowed us to draw out some of the common issues and tensions that were navigated and to produce educational materials for training mediators in understanding farmer landowners issues as well as a guide to help landowners and farmers reflect on their lease relationships.

Education & outreach activities and participation summary

Participation summary:

Land For Good Producer two worksheets. These were given to the five participating farmers and their corresponding landowners to prepare for an initial intake sessions.

1.) Towards, Quality, Durable Farm Leases- Initial Questions for Farmers: Lease Mediation-Farmer Worksheet

2.) Towards Quality, Durable Farm Leases- Initial Questions for Landowners: Lease Mediation-Landowner Worksheet

Land For Good produced Webinar in Land Lease to help mediators working in this pilot project understand the context. To date four mediators, working on the pilot project attended a two hour webinar session.

FarmNet Presentations 8/15/2017 and 8/17/17 : Included 15 minutes about Lease Mediation and our SARE Pilot Project to forty Farm Net consultants working throughout NYS during a one hour presentation on New York State Agricultural Mediation Program

American Farmland Trust, NY: 10/11-12/2017 panelist

NYS Ag. Mediation Project presented a Down to Earth Workshop on 10/25/17 in Hudson NY through Columbia Land Conservancy.The presentation included a power point on lease mediation and an overview of the SARE Lease Mediation Pilot Project.

CLC's description: Small conflicts can become bigger rifts between landowners and farmers. Agricultural mediation can empower both parties to find an inexpensive and lasting solution. Experts will help us understand the mediation process and how many conflicts can be avoided altogether.

NYS Ag. Mediation Program Tabling: NYS Ag. Society 1/9-10/2019- Let's Talk About Farm Your Lease

NYS Ag. Mediation Program Tabling: NOFA, NY 1/19-20/ 2019 -Let's Talk About Your Farm Lease

Coalition Of Ag. Mediation Programs: 5/10-12/2019 North East group meeting on lease case development

NYS Ag. Mediation Program: 12/10/2019 Webinar for Community Dispute Resolution centers in NYS- introducing lease mediation

NYS Ag. Mediation Program Tabling: Empire State Producers Expo, NY 1/14-16/2020- Let's Talk About Your Farm Lease

NYS Ag. Mediation Program Tabling: NOFA, NY 1/17-19/2020- Let's Talk Abut Your Farm Lease

Ag Mediation Program Training: 9/14/2020 Day long online training in Lease Mediation for NYS Ag. Panel Mediators including webinars, presentations and discussion groups and role plays.

Farm Leasing and Conservation Practices Pace Food and Law: Panelist 11/18/20

upcoming:

Farmland For A New Generation, NY: SARE Report and Discussion Guide will be sent to approx 30 Navigators in a newsletter this spring who work with farmers and landowners across NYS

Farmland For A New Generation, NY: Discussion guide will be sent to approx. 300 farmers and landowners on the farmlink mailing list