Final report for ONE22-412

Project Information

Through a collaboration with 3 farms in northeast Connecticut, this project was designed to gain a complete understanding of the use of antibiotics on farm and the impact of that usage on off-farm transport and soil bacterial community gene expression and assemblage. Our partner farms were all family run dairy farms, one larger and two of small to medium size for the region. All farms reported occasional usage of antibiotics across a variety of classes, all of which were analyzed in this project. Though some of the farms had animals other that dairy cows as apart of their operation, this study focused on dairy derived manure and potential contaminants. We analyzed manure and surface water for antibiotic residues and soils for antibiotic resistance genes and community composition. We also analyzed groundwater, surface water, and precipitation for stable water isotopes to generate a better understanding of hydrologic flow paths engaged at each farm. We detected 4 antibiotics and caffeine in surface waters, and 5 antibiotics and caffeine in manure. We detected antibiotic residues year round in both soils and waters tested. We detected antimicrobial resistance to the antibiotics detected and also resistance to antibiotics for which the residues were not detected. Thus far, we have communicated these results to the partner farmers, the scientific community through public presentations, and to undergraduate students through incorporation of results into curricula. We will continue to share these results through peer reviewed and public facing products.

Our broad objective is to understand the transport and impact of antimicrobials in the environment from animal agriculture. We will achieve this by adding additional analyses (antibiotic residues, resistance genes, and soil microbial communities) to an existing project (USDA NIFA AFRI Workforce & Development Postdoctoral Fellowship), allowing us to draw broader impact assessments of antimicrobial usage on dairy farms in Connecticut. Specifically, our objectives are to:

(1) Understand linkages between surface water antibiotic residues, soil microbial communities, and antibiotic resistant genes in soil on dairy farms.

(2) Partner with appropriately compensated farmers to ground this study in on-farm applicability across farm sizes.

(3) Communicate the results of this work to scientific, agricultural, and public audiences to increase cross-sector understanding and support.

Antimicrobial resistance is a global threat, with action and surveillance plans outlined by the United Nations Environmental Program, the European Union, and the Pan American Health Organization among others (UNEP, 2022). Despite championing a one-health approach to addressing this issue, the environmental perspective is lacking from policy-level decisions. The conversation is being driven by human and livestock health professionals while complete environmental assessment of the legacy and impact of antibiotic residues, resistant genes, and bacteria in soil and water systems is given less consideration. Where there has been research in this realm, rarely does it connect multiple or all three of these environmental contaminants and legacy effects to inform agricultural land management.

Anthropogenically sourced antibiotics move into the environment through waste streams. These streams can be from residential wastes via septic systems or municipal wastewater treatment, hotspots tend to be focused around hospital discharges, and through livestock wastes. Because the vast majority of antibiotics sold are for use in animal agriculture, it is critical to understand this pathway. Farm sustainability has depended on the judicious use of antimicrobials in animals and the health of the landscapes. Because of the potential for legacy contamination, and soil microbial and aquatic organism impact, the use of antimicrobials may leave an imprint on the landscape longer than exceeds the awareness of the experts who manage these fields. The long-term goal of this work is to understand the movement and impact of agriculturally sourced antimicrobials through the landscape to inform management practices that limit the chronic impacts of these medical tools and ensure farm sustainability through improved understanding of soil microbial community health and antibiotic residue transport. This proposal supports the development of improved resiliency on farms to address and deal with new microbial diseases and reduce antimicrobial resistance in the disease populations by lowering the selective pressure for those individuals on farms that contain residues in their waste streams. This understanding will benefit not only the sustainability of the farms partnering in this study, but will provide a basis for other farms to work from to ensure sustainability across the region.

To address the above challenges, we will establish paired samples through time with surface water antibiotic residues, soil microbial community composition, and antibiotic resistance genes presence to understand the interactions between these three distinct data sources over the course of the year. In addition, we overlay these samples with a parallel project addressing human dimensions of these contaminants and stable water isotopes as temporal water tracers in the landscape (USDA Workforce and Education Development Grant; PI: Dr. Georgakakos). The fusion of these components will allow for holistic watershed wide understanding of antimicrobials in Woodstock, CT, an agriculturally dominated watershed in Northeast Connecticut.

Under our existing USDA funding, we are obtaining surface water samples downstream of three farms to analyze for antibiotic residues, and calculating antibiotic residue loads to the watershed with the addition of stream discharge measurements. Under this funding, we will expand this monitoring campaign to sample more frequently, and with soil samples from active pasture and field crop fields where manure is spread to assess the impact of residues on the resistance genes present in the soil and the structure of the soil microbial community. Together, these data will allow us to calculate off-farm transport of antibiotic residues in surface water, and pair these measurements with the impact of that transport on the surrounding soil health. We will share detailed results with each of the farms involved, and provide a discussion of possible solutions to off-farm antibiotic transport if results suggest such a management change would be beneficial.

Cooperators

- (Researcher)

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

Research

The study design of this and our parallel funded proposal paired five data types to allow a wholistic understanding of the hydrologic flow paths and impact of antimicrobials on the surrounding soils. We collected stable isotope water data from surface water, soil water, and precipitation to understand the residence time of water through each system and will survey watershed residents (Fall 2024) to assess human perception and impact on these contaminants. We sampled antibiotic residues in surface waters and antibiotic resistance genes and microbial communities in soil. The isotope and human dimensions components along with a portion of the residues were funded under our existing USDA grant. This proposal allowed for the addition of genetic and microbial community analysis and the expansion of antibiotic residue sample analysis to address new, unanswered questions. We sampled three farms within the same watershed (supplementary material, Figure 1). We also sampled the region down stream of all three farms for stable water isotopes and antibiotic residues, through our previously funded project, while this funding allowed for riparian soil analysis for antimicrobial resistance.

Sample collection:

Water and soil samples were collected May 2022 through June 2023 twice monthly using grab sampling methods. This sampling scheme allowed us to see temporal changes in antibiotic residues, resistance gene abundance and soil microbial communities, and also gave us sufficient replication to average samples seasonally to determine variability. Our sampling schedule was approved by the partner farmers to ensure this study did not impact normal farm operations but would still able to capture field and farm runoff of manure-derived contaminants.

Antimicrobial residue analysis:

We have sampled surface water for antimicrobial residues and completed analysis of this component. We also sampled residues found in manure prior to field application to obtain direct source data. Water sampling sites were located immediately downstream of farm runoff confluences. We analyzed for a suite of emerging contaminants through a two-phased approach: we surveyed farmers to obtain a list of all antimicrobials used on the farms and targeted these antibiotics in each sample. Following this targeted analysis, we also preformed a untargeted analysis on a subset of the samples to determine other highly concentrated contaminants. This analysis was completed at the Center for Environmental Sciences and Engineering (CESE) at the University of Connecticut with the mentorship of Dr. Anthony Provatas. Using this approach, we captured the broad story of contaminants derived from both livestock and human sources as well as some breakdown products. All residues samples have been collected and analyzed, with data analysis and modeling remaining to be completed. Emerging contaminant concentrations will be paired with discharge measurements to allow calculation of contaminant loads throughout the year (Spring 2024).

Soil microbial community and antimicrobial resistance analyses:

Soils were collected twice monthly in tandem with soil and manure samples to examine microbial communities and levels of antibiotic resistance. At the time of sampling, we measured temperature, moisture level, and pH of each soil sample. We sampled microbes using Zymo Xpedition Soil/Fecal DNA Miniprep kits and protocols. We analyzed microbial communities by Illumina© sequencing libraries generated by PCR amplification of 16S bacterial and ITS fungal sequences. We examined antibiotic resistant genes (tetM, AmpC, and Sul1) using quantitative PCR methods. All resistance analysis was be completed Fall 2023. All microbial sequences were processed, cleaned and taxonomically assigned using the pipeline DADA2. Subsequent analysis will be done in R v. 3.5.2.

We completed 28 field campaigns collecting soil and manure samples for microbial analysis, along with surface water and manure samples for antibiotic residue analysis and soil water, surface water, ground water and precipitation for stable water isotope analysis. Each field campaign is also accompanied by collection of meta data on soil temperature, water temperature, soil moisture, and stream discharge and soil pH.

Analysis of stable water isotopes occurred throughout the sampling period at the University of Connecticut in the Ecohydrology Lab. Analysis of microbial communities and resistance genes occurred at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies. Analysis of antibiotic residues in surface water and manure is planned for this spring at the Center for Environmental Science and Engineering (CESE) at the University of Connecticut. Below are our results to date all analytes across sites. We have continued to collect samples at these sites beyond the originally planned 1 full year at a reduced frequency. That reduced frequency data is not reported due to delays in analysis. Farms are referred to as Farm 1, Farm 2, and Farm 3 to protect the privacy of the farms, as will be the case in published manuscripts.

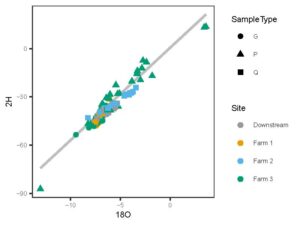

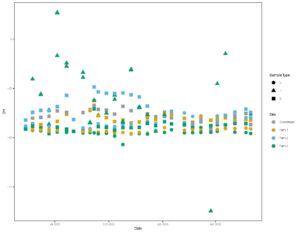

Together, figures 1 and 2 indicate that the three study farms are defined by unique hydrologic flow paths and estimated difference in water residence times in the environment. We use this data to model water ages to determine molecule residence times in the landscape from precipitation event through to discharge from the site. We then pair these residence times with antibiotic signatures in stream water to better understand risk of contaminant transport off these sites, and impact of residence times on soil microbial community and extent of antibiotic resistance gene presence.

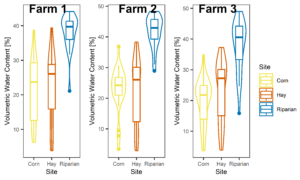

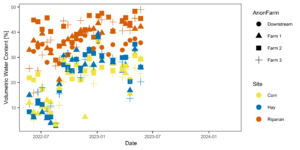

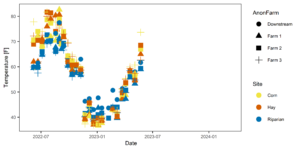

Figures 3-6 display the meta data collected alongside soil and water samples for analysis. These factors (soil moisture and temperature) influence microbial community structure and are therefore important data to have alongside microbial community analysis.

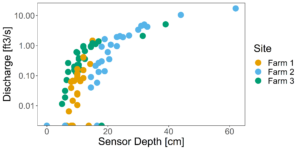

Figure 7 and 8 depict the flow characteristics of the three streams studied. Two of the three sites (Farms 1 & 2) were dry during the months of July and August 2022, while the third site (Farm 3) which displayed stable water isotope signatures similar to the groundwater signatures, continued to flow throughout the dry months. These differing hydrologic regimes may be caused by a variety of factors, which we will explore through modeling exercises.

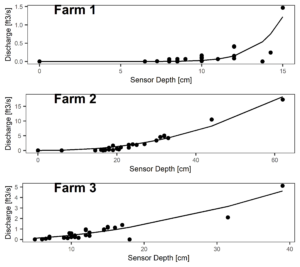

Figure 9 displays the antibiotic concentrations detected in stream water at each study site across time. This figure depicts only those antibiotics (and caffeine) that were above detection in at least one sample. Figure 10 displays the same data as Figure 9, versus discharge to begin to understand when pulses of antibiotic residues are entering stream systems.

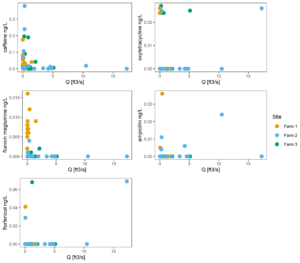

Figure 11 tracks concentration vs discharge, to better understand if higher or lower concentrations tend to be associated with large or small storm events. This figure suggests that this correlation is largely absent from the watershed we studied.

Figure 12 depicts a test for correlation between different residues in the same samples. No residues show significant correlation, suggesting that different flow paths may be taken for different residues, distributing the impact of these contaminants over time.

Figure 13 displays all the residues detected in manure samples over time, while figure 14 shows the same data averaged across all samples. The dramatic difference in the residues detected in manure versus those found across farms in the surface water suggests usage alone of these pharmaceuticals does not predict extent of environmental contamination downstream. From Figures 10 and 14 we can also determine that differences between farms do not necessarily suggest higher or lower concentrations when averaged over time. Instead, certain compounds are more likely to be detected at higher concentrations than others.

Figure 15 suggests that organic carbon-water partitioning coefficients may be helpful in predicting upper limits of antibiotic concentrations observed in streams. However, of the 10 antibiotics tested, only 4 (plus caffeine) were detected in surface waters, so this relationship is not the only controlling factor on compound transport.

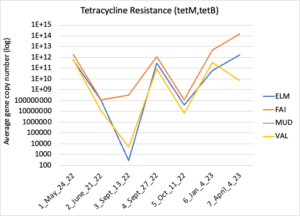

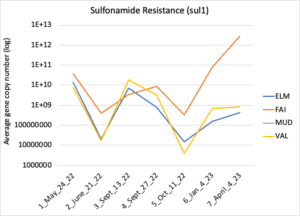

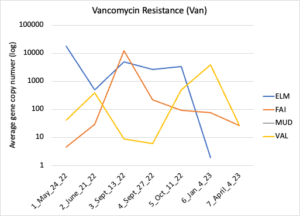

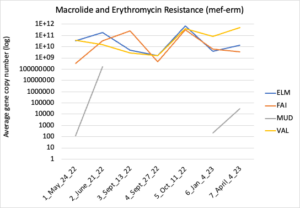

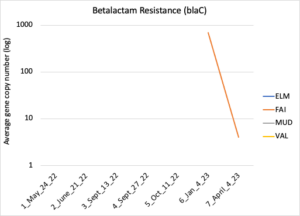

Figure 16 depicts the combined antibiotic resistance profiles detected in a subset of samples across time. These samples are averaged across sampling locations within the farms (i.e. hay, corn, riparian sites). Figure 17-21 depict individual resistances detected. Again, comparison between these plots and the manure residue plots suggests usage alone does not predict resistance patterns.

Figure 1: Dual isotope space of all samples across farms. Ground water (G) and stream flow (Q)samples were collected from all farms, precipitation (P) collected from Farm 3 only.

Figure 2: Time series of all isotope data, including groundwater and surface water at all sites.

Figure 3: Boxplots of all soil moisture data collected at each farm, not separated by season.

Figure 4: Temporal variability in soil moisture across farms (shapes) and sites (colors).

Figure 5: Temporal temperature patterns. Farms are represented by shapes in this figure, colors indicate site (riparian, corn, hay).

Figure 6: Temperature averaged across all sampling points split by site at each farm.

Figure 7: All rating curves plotted together. Y axis is log scale.

Figure 8: Rating curves for each farm with best fit nonlinear regression fit.

Figure 9: Antibiotic concentrations in stream water at each site across time.

Figure 10: Average antibiotic water concentrations averaged across all samples.

Figure 11: Concentration of antibiotics versus discharge at each site.

Figure 12: Test for correlation between differing antibiotics in water samples. Larger contaminant loads are represented by larger points.

Figure 13: Concentration of antibiotics versus time from each farm's manure sample

Figure 14: Manure average concentration of antibiotics across all samples.

Figure 15: Organic Carbon Water Partitioning coefficient of targeted compounds vs. concentration

Figure 16: Combined antimicrobial resistance at each farm on a subset of sampling dates.

Figure 17: Tetracycline resistance across time for each farm. Colors indicate sampling sites (Farm 1: orange; Farm 2: yellow, Farm 3: blue, Downstream: grey).

Figure 18: Sufonamide resistance. Colors indicate sampling sites (Farm 1: orange; Farm 2: yellow, Farm 3: blue, Downstream: grey).

Figure 19: Vancomycin resistance. Colors indicate sampling sites (Farm 1: orange; Farm 2: yellow, Farm 3: blue, Downstream: grey).

Figure 20: Macrolide and erythromycin resistance. Colors indicate sampling sites (Farm 1: orange; Farm 2: yellow, Farm 3: blue, Downstream: grey).

Figure 21: Beta lactam resistance. Colors indicate sampling sites (Farm 1: orange; Farm 2: yellow, Farm 3: blue, Downstream: grey).

Our complete results and conclusions are planned for publication in 3 upcoming manuscripts, one focusing on chemistry and occurrence of residues in these systems, the second focusing on stable water isotope modeling and using this tool in conjunction with residue data to understand hydrologic flowpaths, and the last on the impact of these residues and transport on soil microbial communities. These manuscripts are all in preparation with anticipated publication in 2025. The general objectives of this study were met, though our formation of formal results is ongoing. Importantly, this study allowed the establishment of a working relationship with all three farms whereby we have been given extended access to these sites for long-term monitoring.

Antibiotic residues are being transported off of farms through a variety of flow paths. That transport occurs both at farms that experience primarily surface water flow (Farm 2) as well as farms that experience primarily groundwater or subsurface flow paths (Farm 3). Despite having one of the higher average usage rates, Farm 3 has average to low water concentrations of antibiotics. This may be explained by the flow paths these contaminants travel and the effective filtering of soil in these cases.

Differences in concentration of contaminants was much more explained by contaminant than by farm. As a result, compound characteristics such as organic carbon-water partitioning coefficients were analyzed to determine potential predictors of elevated environmental concentrations.

Antibiotic resistance genes were detected for antibiotic residues detected in manure as well as residues not detected in manure. This generalized increase in resistance with exposure to a suite of residues over time tracks with results other researchers have observed. We will continue to parse apart the antibiotic resistance data to understand broader impacts of spreading manure with resistance genes. Resistance gene presence also fluctuated across time, with closer agreement between farms that might be expected given the different usage rates the 3 farms displayed. Such tight correlation might suggest that these resistance genes are also controlled by other environmental factors.

Conversations with our partner farms have suggested surprise at detection of antibiotics in their water systems. These conversations spurred interesting follow-up conversations regarding other contaminants (hormones, dewormers, etc) that might also be moving around their farms. Such conversations are critical to initiating change in behavior around the usage of these compounds on farms.

Education & outreach activities and participation summary

Participation summary:

The results of this work will be disseminated through several publications and in-person conversations as planned after publication of peer reviewed manuscripts. Due to the one-health nature of this problem, it is critical that information is spread beyond the academic environmental contaminant silo and into the other areas using and contributing to antimicrobial resistance. These areas include agricultural communities for their use of antibiotics in livestock, scientists studying contaminant transport and environmental effects of antimicrobials, and the public which uses antibiotics for health reasons.

The Partner Farmers:

All results will be shared with the partner farmers both in the form of copies of publications as well as through an in-person, end of study meetings. One of these meetings has happened to date, along with a report of findings of the study. These meetings allowed for a dialog about on-farm research, suggested future research directions, and results specifically applicable to the partner farmer and the agricultural community in general.

The scientific community:

Final results will be published in 3 manuscripts submitted to the Environmental Science and Technology. All data will be made publicly available through USDA’s Ag Data Commons for future use in modeling and informing broader synthesis studies. Publication of these manuscripts is on-going.

Agricultural community:

Several publications in local trade magazines will communicate the results of this study to the farming community. Specifically, we will submit pieces to Hoard’s Dairyman to reach the dairy community at the national level, and cooperative extension blogs and newsletters (e.g. CCE SCNY Dairy and Field Crop Team Blog) to discriminate these results in the regions not directly involved in the study. These publications will begin following manuscript publication and acceptance.

The public:

The results of this study will also be shared in regional newspapers (e.g. The Hartford Courant) to facilitate public understanding of on-farm systems and the one-health approach to antimicrobial resistance mitigation. We will also participate in a public in-person and virtual science conversation at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies. This science conversation is an opportunity for researchers to explain their work to the broader public and answer questions. Additionally, I have run one Master Teacher Training Workshop series which has shared results of this study alongside methods for evaluating water quality concerns with K-12 teachers around New York State, and plan to run this workshop annually, incorporating this and other data.

Undergraduate Students:

I have included results from this study in several courses I teach at SUNY ESF (ERE 496: Engineering Sustainable Agriculture Systems, ERE 133: Intro to Engineering Design, ERE 340: Engineering Hydrology and Hydraulics) and in courses where I have been invited as a guest lecturer (ERE 132: Intro to Environmental Engineering, SRM 498: Agroforestry). Inclusion of this data has excited learners and peaked interest in careers that merge environmental sciences and sustainable agriculture. My course Engineering Sustainable Agriculture Systems was inspired by the interdisciplinary nature and impact of this work.

Learning Outcomes

After sharing results from their farm and the other partner farms from this study, all partner farmers expressed surprise at our detection of antibiotic residues in surface waters and manures. These conversations allowed us to engage in how veterinary tools can become contaminants, and the lasting impacts of long-term use on their soils and streams. All partner farmers were excited to engage in such a conversation, especially with data so relevant to their farms. By participating in this study, farmers awareness of antibiotics as environmental contaminants increased, though we did not formally assess this change.

Project Outcomes

Through conversations with partner farmers, it seems evident that this research and our results changed the way they think about contaminant flow in their landscapes. One partner farmer identified additional compounds, to consider for future monitoring (hormones), that they believed were equally ubiquitous across the dairy industry. Though our work does not directly tie back to efficacy of compounds in animals to point to lowering usage while maintaining herd health, this work does point to elevated levels of antimicrobial resistance in soils of all three farms.

The methods we applied in this study were effective at leveraging existing data to more fully understand the system in which we were working. Pairing water and residue data with soil and manure resistance data allowed us to connect drivers of antimicrobial resistance with monitored levels. I will continue to use this paired methodology to understand these drivers of contaminant transport. There is substantial need for additional work on this topic to determine fluctuations in microbial resistance in their connection to climatic drivers as their fluctuation seems to be independent of manure application timing, rates, and farm practices.