Final report for ONE22-418

Project Information

The benefits of buckwheat to the soil are obvious, but today's modern grower needs to know that buckwheat can pack a bigger punch with more impact to both acreage and revenues. This project seeks to understand the environmental, sustainability, and financial viability of double-cropping no-till buckwheat after wheat harvest.

We want to answer the following questions:

- What planting dates produce a viable buckwheat yield?

- Which planting dates provide an optimal amount of vegetative growth?

- Which planting dates allow the grain to mature enough for harvest before frost?

- Which planting dates result in acceptable seed fill (test weight)?

- How much contamination from the prior grain ends up in the buckwheat (which must be gluten-free)?

- Can buckwheat growers double-crop after wheat, thus taking advantage of normally idle acreage and increasing revenues

- How are yields impacted if using no-till practices?

- Can buckwheat improve soil conditions for future crops, thus increasing yields and raising revenues for growers on those crops?

At the height of the American buckwheat boom in the 1860s, over 1 million acres were planted. Nothing could beat buckwheat’s ability to grow quickly in unimproved soil (maturing to harvest in 90 days, much quicker than wheat at over 200 days) and feed people. With more nutritional value than traditional grains, it was unrivaled as a fast “pioneer crop.” “Buckwheat is one tough customer,” says Klaas Martens, a third-generation farmer in Penn Yan, New York. “You can throw it in dust and it’ll sprout.”

But, as chemical fertilizers came on to the scene, production of buckwheat decreased.

“The balance [of nutrients] in the soil is something that farmers picked up intuitively over the years but were ‘freed from’ when we started inventing synthetic fertilizers and pesticides,” he explains. “[The fertilizers and pesticides] allowed us to plant whatever we wanted or made the most money on.” Klaas knows about this firsthand. He originally worked his land conventionally, but he ultimately experienced negative health effects that he related to the use of chemical herbicides on his fields.

Looking at his own farm, Klaas was inspired by the idea that farming methods and crops like buckwheat could hold the solution to pest and weed control and show the way beyond chemical fertilizers. Plants need phosphorous, but it is typically chemically bound to other minerals and unavailable. Buckwheat roots can dissolve those chemical bonds, freeing phosphorus in amounts that exceed what the plant itself needs for growth. In essence, buckwheat unlocks the door, helping transition the soil and create a supportive environment for subsequent crops without the need for chemical fertilizers.

Why in the Northeast?

The Birkett Mills is one of the largest buckwheat mills in North America, and the only one east of the Mississippi River. The Birkett Mills continues to see increased demand for its products because buckwheat is gluten-free, packed with health benefits, and a versatile grain that can be used in a variety of ways. This means The Birkett Mills has an acute demand for more buckwheat, and will be a consistent marketplace for growers to sell their buckwheat. If our experiment yields positive results, it could substantially increase potential revenues for local growers.

There is a potential to 'unlock' several thousands of acres in our local region if more growers adopt buckwheat as part of their rotation. With the current market rate of buckwheat, growers could generate revenue anywhere between $350-$500 per acre in just 90 days from planting to harvest. This presents a huge economic opportunity to local growers and potentially idle land. This means this grant could lead to potentially $500,000+ in economic impact to local growers and our economy.

Changing Climate

Planting later, when days are shorter, would induce buckwheat to be less vegetative. This double-cropping scenario would then greatly increase the number of growers who would consider contracting buckwheat. Farms near the Finger Lakes and Lake Ontario have substantially warmer fall weather than the surroundings, making double-cropping a possibility.

Environmental Benefits

No-till, or reduced till, is widely used by growers in the relevant region. Adoption in recent years has resulted in growers hoping for additional benefits from the practice. No-till buckwheat after wheat has been successful in Ohio. With recent climate change, the autumn in Central New York has been warm enough for this technique to work here.

No-till planting would reduce erosion. Buckwheat also loosens the soil enough that planting the following spring is likely to use gentler soil preparation or disturbance.

Cooperators

- (Researcher)

- - Producer

- (Educator)

Research

To do this experiment, we used 100 acres on Hemdale Farms - located in Seneca Castle, New York. Hemdale Farms has been using a mixture of no-till/minimum till practices for several years, and has access to all the proper equipment in order to conduct this experiment under Dr. Bjorkman's design.

The experiment tested four planting dates: 0 days, 5, 10, and 15 days after wheat is harvested. Again, we wanted to test how well wheat can be 'double-cropped' using buckwheat.

There were five different fields of varying plot sizes. At each planting date interval, we had three replications. For example, at 0 days after wheat harvest, planted on Field A, Field B, and Field C. At 5 days after harvest, we planted on Field D, Field C, and Field E, ... etc. The idea behind using 5 different fields is to allow us to have enough acreage to test, but also account for varying soil conditions, etc

Specific instructions were given from Dr. Bjorkman to the Hemdale Farms team during each planting, plus he gave instructions for crop management (swathing), combining, pickup and delivery.

With state of the art testing and cleaning equipment, we were able to quantitatively test the following:

- At The Birkett Mills

- Overall yield per acre of food grade quality buckwheat

- Test weight

- Moisture

- Percentage of glutinous grain

- At Hemdale Farms

- Increase yield of future crops where buckwheat was planted

We were also able to test qualitatively at Hemdale Farms the overall soil health improvement, looseness, etc.

Because of the late wheat harvest, we were only able to plant buckwheat on 52 acres of land versus the original 100 we had planned. We planted the 52 acres across 2 different sites and 4 planting dates. When we initially started the project, the goal was to use a swather in order to cut the buckwheat to then direct combine 7-10 days later. Finding an acceptable swather proved difficult & Hemdale Farms elected to direct cut the buckwheat. In the past, this has lead to slower harvest & lower yields than swathing & that was no exception here.

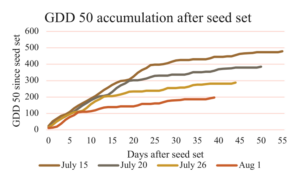

This year’s temperatures were quite normal. July 15 through October had 1467 GDD50. The average is 1434, with a range of 1116 to 1721 in the last 50 years. The soil was fairly dry at planting, but emergence was rapid and plants grew well. The temperature cooled off about September 21, causing growth to slow. The leaves were killed by a light frost on October 18. The recent mean date of first frost is October 11, with a 10% chance before October 1. The growing degrees during seed fill varied greatly among planting dates

It takes about 350 GDD50 to get a ripe crop. From climate data, the likelihood of having enough heat can be calculated for each planting date. See attached graph showing how this looked based on planting date.

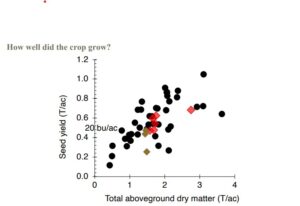

The crop grew to a fairly typical size of about 1.5 tons of dry matter per acre. Black circles are historic data from commercial fields of Koto buckwheat. The red diamonds are the from the Ma site. The brown diamonds are the SH site, with the lowest seed amount in the last, August 1, planting. A somewhat larger biomass around 2 tons would have more yield potential.

There is inevitably some volunteer wheat after wheat harvest. These fields had lodged some, resulting in more seeds than usual and more long straw in the chaff strips. That provided a good opportunity to assess the effect.

The chaff row grew and yielded poorly. That accounted for about 10% of the field. It is likely that it is not worth doing anything in the buckwheat crop and just accepting the lower yield. Alternatively, it could be worthwhile to spread the chaff more uniformly and to kill the wheat seedlings better.

Seed set was determinate. The late planting date and modest fertility caused the plants to be effectively determinate, making seed on the axillary inflorescences at nodes 4, 5 and 6, and having a terminal head. This pattern of seed set is ideal.

The combine delivered very clean seed with low dockage. The moisture content was acceptable, albeit above what is obtained with swathing. The moisture in the 7/26 planting was slightly higher than the 7/20 planting.

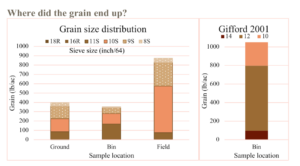

Small Seed. Of the grain that was on the plants, about 600 lb/ac was large enough to use (Sieve >10). The later planting resulted in shorter seed fill for the late-set seeds, resulting in smaller kernels. Undersized grains accounted for about 30% of the seeds, where 20% is normal (See Gifford 2001 Koto sample for comparison.)

Combine efficiency. The combine had a lot of trouble separating chaff from grain. The grain in the bin was very clean with 90% being over 10 sieve and dockage between 1 and 2.5%. However, about the same amount of seed went on the ground as in the bin.

Education & outreach activities and participation summary

Participation summary:

Dr. Björkman coordinated 5+ phone calls with team at Hemdale Farms in preparing & executing the study. Along with working with Hemdale Farms, he also spoke extensively to Klaas & Peter Martens as they have many years of experience in planting & harvesting buckwheat. The initial proposal was pushed by Klaas as he believes buckwheat can be a great crop for farmers to plant after wheat.

After setting up the study, Dr. Björkman was on site during the different planting periods to educate & oversee the team at Hemdale Farms. After planting, he continued to followup on the progress of the crop as he evaluated the different planting dates & the effect it had on yields for the farmer.

As it got closer to harvest time, he took a team from Birkett Mills to the different fields to educate them on the stages of buckwheat. Although Birkett's has been milling buckwheat for 200+ years, they do not have the expertise on the farming side that Hemdale / Martens / Dr. Björkman has. This education was helpful to the team at Birkett's, as it allowed them to better answer farmer calls regarding the readiness of their crop to harvest & what signs to look for.

During this time, Dr. Björkman also made multiple trips to the receiving house at Birkett Mills in order to evaluate the condition of the grain. He used the information gained here in his research report.

There will be several different layers of outreach that The Birkett Mills and Dr. Björkman will do.

Dr. Björkman prepared a detailed report. This report has been sent to different farmers / food who were interested in learning more about double cropping buckwheat in NYS. Dr. Björkman & Kyle Gifford from The Birkett Mills also presented at the Annual NOFA Conference in Jan 2023 on the report & of the strong market for buckwheat in NYS.

The Birkett Mills continues to educate local growers in the opportunity that exists to double crop wheat after buckwheat. As a partial outcome of this work, more acres of buckwheat were contracted in NYS in 2023 than any time in Birkett's long history.

Learning Outcomes

Planting buckwheat after wheat worked reasonably well. Buckwheat needs to be planted within a week of wheat harvest so that it will outcompete wheat volunteers and weeds.

In sites where the first frost is likely to be late, it can be planted as late as July 26. The proportion of undersized seed is likely to increase too much if planted later.

The lower fertility after wheat balanced the tendency to become overly vegetative on high-fertility soil.

The potential yield is modest, 600 to 1000 lb/ac.

A combine designed for buckwheat is necessary. Having a custom harvester who can both swath and pick up with a straw-walker combine would be ideal. That way each grower would not need specialized knowledge and equipment.

There are areas with significant potential to support a custom harvester in Western New York, including the area immediately north of Penn Yan.

Potential for double-cropping buckwheat after wheat in warm and fertile sites in New York.

Buckwheat is not normally raised on high-fertility soils because of excess vegetative growth and the low financial return if single cropped. Both of these limitations might be overcome by double cropping after wheat.

Double cropping has not been practiced in New York because the later planting date generally would not let the crop mature before frost. There may be enough time, at least in protected sites near lakes, due to the later frost dates in recent years.

We tested this proposition with a sequential planting at Hemdale Farm in Seneca Castle. The approach was to replicate what would work for a field-crop grower.

- No till drill after wheat harvest to minimize time and cost

- Control weeds and volunteer wheat with glyphosate

- No fertilizer or pest control to minimize time and cost, since residual fertility is

substantial. - Direct-cut harvest since that equipment is most available

Project Outcomes

Buckwheat can be double cropped as late as July 20, possibly July 26.

Wheat straw should be spread evenly to avoid suppressing buckwheat.

The JD rotary combine left about half the yield on the ground. The broken straw and leaves held the grain. Since most wheat growers have rotary combines that will have this problem, it is necessary to identify ways to harvest only with combines that separate well. Many buckwheat growers have used Gleaner combines from the 1960s, but almost all of those are completely worn out.

Swathing is worth examining. A local operator could provide that as a service, along with a pickup head or a relevant combine with pickup head. Let’s find out who is available now and what the business case would be.

Potential benefits include reduced input needs and the opportunity for double cropping on high-fertility soils.