Progress report for SW22-936

Project Information

Sweet potato is economically and culturally important in Hawaii. Sweet potato was the highest revenue-generating vegetable crop in Hawaii until challenged by multiple pests, in particular the sweet potato weevil (Cylas formicarius elegantulus). While weevil feeding may cause vine damage, the more serious problem is to the tubers. Larvae tunnel resulting in spongy tuber that is dark in color. Additionally, larval feeding causes tubers to develop  a bitter taste and a terpene odor. Losses to the weevil range from 30 to 97% across farms. Producers in Hawaii have turned to pesticide-intensive management tactics spanning the time from planting to harvest. Growers sometimes rely upon weekly insecticide applications to ensure a marketable crop. Non-chemical based integrated pest management strategies are needed and entomopathogenic nematodes (EPN) are a promising candidate.

a bitter taste and a terpene odor. Losses to the weevil range from 30 to 97% across farms. Producers in Hawaii have turned to pesticide-intensive management tactics spanning the time from planting to harvest. Growers sometimes rely upon weekly insecticide applications to ensure a marketable crop. Non-chemical based integrated pest management strategies are needed and entomopathogenic nematodes (EPN) are a promising candidate.

The weevils are susceptible to Heterorhabditis sp. and Steinernema sp. These EPN have met with some success in managing sweet potato weevils in other growing areas. We propose to use EPN-infected larvae, sometimes called living bombs, to control the sweet potato weevil. Living bombs, or EPN-infected larvar, entail placement of the EPN-infected insect cadavers into the field rather than aqueous application of Infective Juveniles (IJ) that have exited the cadaver and been collected.

One objective will be to demonstrate the efficacy of H. indica and S. feltiae in reducing weevil damage in sweet potato in Hawaii. Traditional EPN application methods utilize inundative release of billions of EPN/ha in an aqueous solution. Delivery of the EPN in cadavers will allow for lower numbers and a consequently less expensive tool for growers. Another objective will be to compare the efficacy of different delivery methods of H. indica and S. feltiae. All EPN applications (sprays or bombs) will be compared to the standard practices of cooperating sweet potato producers. Since the focus is to transfer pipeline technologies to growers, our final objective is to convey the information to growers and other practitioners. We will develop videos, extension publications, newsletter articles, and scientific publications to share information. Initially, we will serve as a source for the EPN via a fee-for-service while the nascent demand for EPN builds and before commercial operations enter the Hawaii market. The potential impact of the project is the adoption of environmentally safe and sound biological control for sweet potato weevil by the key sweet potato producers that will then model and influence adoption by fellow sweet potato growers. The co-PIs have statewide connections to share project outcomes through social media, e-mail lists, and newsletters. The project team will work closely with leading growers and extension agents to foster adoption. Our longterm goal is to promote sustainable sweet potato cultivation through economic and environmentally sound pest management.

We propose to use Entomopathogenic Nematode (EPN) infected cadavers, or living bombs, to control the sweet potato weevil. We have two research objectives and three educational objectives. Our research objective 1 will be to demonstrate the efficacy of Heterodera indica and Stienernema feltiae, different species of EPN, in reducing weevil damage in sweet potato. Research objective 2 will be to compare the efficacy of spray applications to living bomb delivery of H. indica and S. feltiae documenting that fewer EPN are needed for effective weevil management when delivered as living bombs. Our educational objectives are (1) to impart knowledge about EPN for IPM control of sweet potato weevil, (2) to illustrate the application of EPN living bombs, and (3) to demonstrate the utility of EPN living bombs as an additional IPM tool for control of sweet potato weevils.

|

|

Year1 |

Year 2 |

Year 3 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Q1 |

Q2 |

Q3 |

Q4 |

Q1 |

Q2 |

Q3 |

Q4 |

Q1 |

Q2 |

Q3 |

Q4 |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Research Objectives |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

EPN culture |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

1. Efficacy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Field demo 1 |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Field demo 2 |

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Analysis |

|

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

2. Application Comparison |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Field demo 1 |

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Field demo 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Field demo 3 |

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Field demo 4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Analysis |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Educational Objectives |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

1. Impart knowledge field days |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

2. Illustrate living bombs workshops |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

3. Assess utility |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Videos |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Newsletters |

|

X |

|

X |

|

X |

|

X |

|

X |

|

X |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Publications |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Reporting |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Drafting and Writing |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

|||||||||||||||||

The boxes show the initiation and the completion of the different activities. Field days and workshops boxes represent the quarter in which the one-day events will be held. For newsletters, the boxes represent publication quarter.

Cooperators

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

- (Educator and Researcher)

- - Producer

Research

Entomopathogenic nematodes (EPNs) are deadly to certain insects and consequently have great potential as biological control agents. Two of the most important aspects for EPN to be successful biological agents are their ability to be mass produced and properly formulated. EPNs are usually applied as foliar sprays or via irrigation without much formulation. The Infective Juveniles (IJs) perish rapidly in low oxygen, at elevated temperatures, low humidity, or when exposed to ultraviolet radiation (UV), necessitating protective methods to maintain their viability and infectivity. Infected-host cadavers are a novel application method in which the insect cadaver protects the EPN from UV and desiccation and thus enhance the efficacy of the EPN.

Demonstration of the efficacy of H. indica and S. feltiae (Objective 1): Demonstrations will be established in each producers’ field. The demonstrations will consist of a no-weevil treatment, standard producer practice (this varies among the cooperators), and EPN applications of H. indica, S. feltiae, or O. tipulae. Plots size and layout will vary and be tailored to each cooperators operation. EPN will be applied within 3 weeks after planting and monthly until harvest. The EPN will be applied at 2 x 109 IJs/ha as an aqueous spray and as EPN-infected cadavers. Aqueous applications will be directed under the leaves and at the plant stems. EPN-infected cadavers will be placed on the ground near sweet potato stems at regular intervals to achieve the desired rate. At harvest, sweet potato yield will be recorded. Weevil damage to the swollen roots will be evaluated and a random 1 kg swollen root sample will be assayed for weevil population density and life stages. As general target, plots will be 2 beds wide by 5 m long. Treatments will be randomized with 4 replications on each farm. Data will be analyzed for variance and differences among treatments. A field day will be held to highlight difference and educate other growers of the potential for EPN as a management tool.

Comparison of application methods (Objective 2): Similar to Objective 1, demonstrations will be established in each producers’ field consisting of a no weevil treatment, the standard producer practice, a postplant aqueous application of the EPN, an EPN-infected cadaver, and a postplant application of EPN formulated in sponge. EPN applicaiton will commence 2 weeks after planting and continue monthly until harvest. Application rates will all be equivalent to 2 x 109 IJs/ha. At harvest, sweet potato yield will be recorded. Weevil damage to the swollen roots will be evaluated and a random 1 kg swollen root sample will be assayed for weevil population density. Data will be analyzed for variance and differences among treatments.

Outreach: Video will be taken of the spray application and bomb application to educate growers in the appropriate techniques to apply EPN for sweet potato management. Field days will be scheduled to highlight efficacy and differences among treatments and to educate other growers of EPN as a management tool.

In demonstrating EPN efficacy, we experienced extremes in sweetpotato weevil pest pressure. In two demonstrations, the sweetpotato weevil pressure was so extremely high, EPN applications were ineffective. The EPN were overwhelmed by the weevil population and any reduction in sweetpotato weevil populations were not sufficient to produce a marketable crop. In other demonstrations, the untreated controls yielded similarly to the EPN treatments because there were not sweetpotato weevils to control.

EPN Efficacy

We compared water applications of EPN to an EPN infected-cadaver application. EPN application rates were 2×109 Infective Juveniles (IJs)/ha for all EPN treatments. Three days after application of EPN-infected cadavers, 100% of cadavers were located demonstrating that the cadavers were not eaten by birds, ants, geckos or other scavengers. The application method (water vs cadaver) did not have a statistically significant impact on sweetpotato yield. A numerical difference in yield was noted between the EPN treatments compared to the untreated control. The aqueous application of Steinernema feltiae and the cadaver application of Heterorhabditis indica increased sweetpotato yield the most (P<0.05). We did not detect the sweetpotato weevil in the first or second repeat of the experiment. All sweetpotato yield was marketable due to the lack of sweet potato weevil damage in the first repeat. In the second repeat, the plots suffered from substantial stem borer damage. Of the little sweetpotato yield obtained, none suffered from weevil damage. The EPN treatments had no effect against the stem borer.

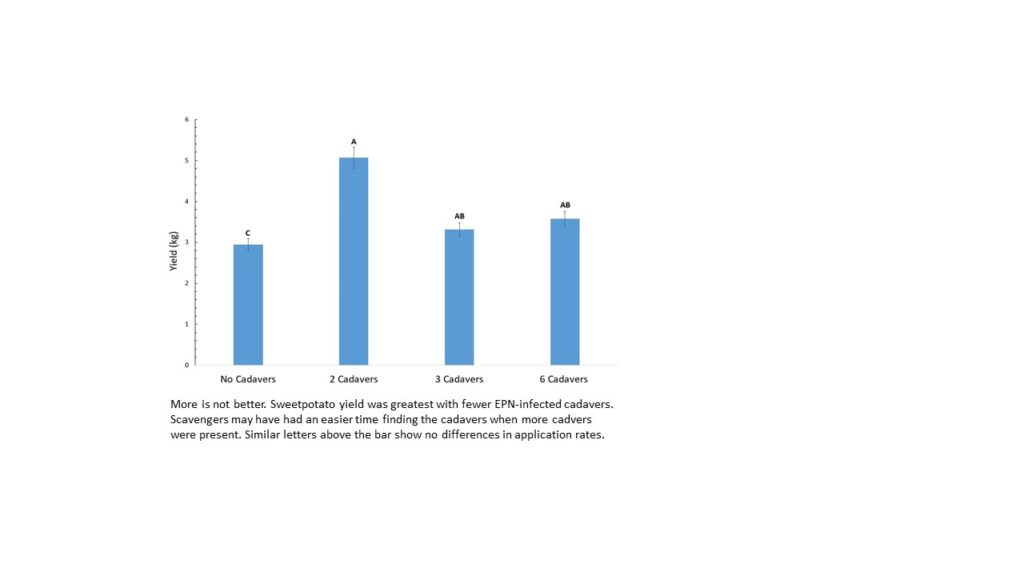

In a separate experiment, the efficacy of 2, 3, and 6 infected cadavers/m of row were compared. This was equivalent to IJ applications of 0.5X, X and 2X or 500 million, 1 billion and 2 billion IJ/ha. We found that increasing the number of cadavers/row did not increase EPN efficacy against sweetpotato weevil. Unexpectedly, the low cadaver application, ie. 2 cadavers/row, resulted in the least amount of sweetpotato weevil damage. We hypothesize that the increased number of cadavers made it easier for scavangers (like birds, geckos, slugs, or rodents) to locate and consume the EPN-infected cadaver, thus reducing the overall application rate of EPN and subsequent efficacy against the sweetpotato weevils.

The results from our field demonstrations prompted us the undertake two additional investigations. A more accurate measurement of sweetpotato weevil populations might allow adjustments to EPN applications to provide better management of the pest. Since EPN-infected cadavers were likely consumed by scavengers, alternatives that protect the EPN like the cadavers but are even less palatable to scavengers might also enhance EPN efficacy.

Sweetpotato Weevil Populations

Currently sweetpotato growers base their assessment of sweetpotato weevil populations on their experiences from the previous cropping cycle and plant their IPM strategies on that information. A few growers use pheromone traps to monitor sweetpotato weevil populations. Neither approach is particularly accurate or timely. Consequently, the growers employ a calendar-based pesticide application approach in most instances. Sweetpotato weevils are cryptic in nature. The insects are not particularly good fliers and females deposit their eggs near the soil line or follow cracks in the soil peds to lay eggs in the swollen roots of the sweetpotato. We evaluated pheromone traps, pit fall traps, Berlese funnels, sweep nets, and elutriation as methods for early detection and monitoring of sweetpotato weevils. In one field, we monitored using pitfall and pheromone traps. Over the 17 week crop growing period, nearly 1000 weevils were collected in the pheromone trap but only 2 weevils were recovered from 16 pitfall traps over the same time span. In a separate field, we placed pitfall and pheromone traps, collected soil samples, and used a sweep net to monitor sweetpotato weevil populations. The pheromone traps collected 5 weevils over the cropping period. The pitfall traps, the Berlese funnel, soil elutriation and the sweep net of the same field recovered no sweetpotato weevils. However at harvest, all of the sweetpotato roots collected were infested with sweetpotato weevils at a moderate level of 3-4 weevils/swollen root. We have not identified a timely method to determine sweetpotato weevil presence and population in the field. We have been targeting EPN application commencing at root swelling but have had the greatest management of sweetpotato weevil when monthly applications started 1 month after planting rather than at commencement of root swelling.

Better Applications

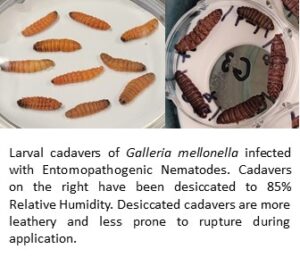

Infected-host cadavers, however, are fragile thus developing an EPN infected-cadaver that resists breakage would be beneficial. Laboratory experiments were conducted with Galleria mellonella and Tenebrio molitor infected with Heterorhabditis indica OM-160 or Steinernema feltiae MG-14 respectively. The cadavers were desiccated to 85% relative humidity with KCl. Cadaver weight of G. mellonella infected with H. indica was reduced by 40% with cadavers becoming leather-like and more resistant to rupture. Desiccated cadavers of G. mellonella infected with S. feltiae remained pliable and ruptured when handled. IJs of S. feltiae emerged prematurely from cadavers of T. molitor during the desiccation period and H. indica OM-160 reproduced poorly in T. molitor. Infective Juveniles (IJs) of H. indica collected from desiccated and non-desiccated cadavers of G. mellonella were evaluated for infectivity and viability on larvae of G. mellonella, T. molitor, and Oryctes rhinoceros. Desiccated cadavers of G. mellonella infected with H. indica yielded equal numbers of IJs compared to non-desiccated infected cadavers (P>0.05) with both averaging over 200,000 IJs of H. indica/cadaver. IJs of H. indica emerging from desiccated and non-desiccated cadavers killed 100% of G. mellonella larvae, 40% of T. molitor larvae, and 94% of O. rhinoceros larvae. The delivery of H. indica through infected cadavers of G. mellonella can be improved by desiccating the infected cadavers. The number, infectivity, and viability of IJs were not adversely impacted by desiccation.

While desiccated proved easy to handle, the may be prone to scavaging. Consequently, the survival, recovery, and infectivity of IJs of S. feltiae were formulated on cellulose and microfiber sponges and stored for 14, 30, and 60 days. Nematodes formulated onto 1 cm sponge cubes and stored at 15°C. IJ infectivity was assessed on larvae of G. mellonella. Both cellulose and microfiber sponges maintained IJs infectivity significantly better than the filter paper control. However, no significant difference was observed between the two sponge types, suggesting that either could be used as a substrate for further formulation. Storage duration significantly affected infectivity, with IJs stored for 14 and 30 days causing higher larval mortality within 24 hours compared to IJs stored for 60 days. No significant interaction was found between sponge type and storage duration. Cellulose and microfiber sponges preserve EPN viability for up to 30 days, while longer storage (60 days) reduced infectivity. Further optimization of formulation methods is necessary to address desiccation, ultraviolet radiation, and temperature protection to enhance the long-term EPN storage for biocontrol applications are required and these treatments can be compared to the infected-cadaver delivery method for efficacy.

Research outcomes

Our recommendations for the use of EPN in a sweet potato cropping system are multi-fold. EPNs can be an effective tool to manage sweetpotato weevil under the right application schedule. Timing of EPN application is critical. Evidence points that applying EPNs soon after planting is better that begining application when the sweetpotato roots begin to swell. Since sweetpotato weevils are cryptic and it is difficult to measure their population denisity, early control is necessary for effective biological control. EPNs need to be present early to prevent the sweetpotato weevils from laying eggs in the plant stems. EPN-infected cadaver (living bomb) applications are as effective as aqueous EPN applications but more cadavers are not better. To intensive EPN-infected cadaver application results feeding scavengers feassting on the cadvers and reducing the effective application rate of EPNs. To effectively use EPN for sweetpotato weevil control, the weevil population and subsequent pest pressure must not be too high. EPNs preform best at low to moderate pest pressure consequently, commencement soon after planting is recommended.

Education and Outreach

Participation summary:

Our education and outreach activities focused on written and video content. During the fall of 2024, we concentrated on video and web content development. Using soil health and biologically-based insect pest management we drafted material but encounted production issues that delayed final development. We presented 5 papers targetted to scientific audiences at the Society of Nematologists Annual Conference in Park City Utah; The Organization of Nematologists of Tropical America in Igaucu, Brazil; and at the College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resilience Research Symposium in Honolulu, Hawaii. The presentations were entitled "Precision EPN applications – Infected cadavers as an optimized tool for integrated pest management," " Organic approaches to manage sweet potato weevil (Cylas formicarius) using entomopathogenic nematodes and entomopathogenic fungi in Hawaii," "Effects of entomopathogenic nematodes and entomopathogenic fungi on nontarget soil surface arthropods and nematodes," "Management of Cylas formicarius using entomopathogenic nematodes," and "Evaluating microfiber and cellulose sponges for entomopathogenic nematode formulation and storage." Each presentation was made to an audience of 25-30 people.

Growers and agricultural pest managers recognize EPN as a possible biological control agent against insect pests. This assessment is supported by the questions asked and interest expressed in EPN for insect management and different venues. Growers are aware of the EPN alternative and seek more information around the use and availability of EPN for insect control.

Education and Outreach Outcomes

Our educational and outreach activites have highlighted producer interest in EPN. This interest can be facilitated and encouraged by providing addtional online resources for growers. This is motivation to keep EPN as biological control organisms in producers' minds. Growers seem to be more satisfied with in-person interactions than solely electronic interactions.

- Entomopathogenic nematodes

- Biological control options

Entomopathogenic nematodes