Final report for FNC15-985

Project Information

Martha and I began our operation in 1982 with 2 acres of blueberries. Through the years, we added additional blueberries, blackberries, gooseberries, plums, shiitake mushrooms, elderberries, a restaurant and a commercial kitchen in which we add value to our produce as well as doing processing for other farms in our region. We conduct a year-round mail-order business shipping our jams, sauces, syrups and baked goods. We find that the primary attraction for our guests is our you-pick blueberry operation, which sets the tone for our farm guests. Our dependence on our blueberry operation is why this project is vital to our farm. We have 75 acres, which includes all cultivated land, buildings and parking areas. Currently we have about 7.5 acres of blueberries, 1 acre of blackberries, .33 acre of elderberries and a few rows of plums and gooseberries. The farm and our processing operation is my full-time work. We have 5 full time workers and a book-keeper. Beyond being a sustainable agribusiness, the mission of our farm is three-fold, First: to provide a family farm destination experience with top quality direct-to-the-consumer produce and products. Second: To provide a healthy, positive environment for families and friends to enjoy harvesting their own high-quality food and to enjoy farm-to-table dining, and Third: To provide our employees with a good place to work and stable employment throughout the year.

During the 30+ years we have been raising blueberries in the Missouri Ozarks, we have noticed a decline in the vigor and productivity of a field after it reaches 20 to 25 years of age. Typically at that time, in our area, growers who have found it necessary to replant in the same location have had problems getting new plants established. This is particularly a problem on you-pick farms where all of the farm facilities such as parking lots, check-out buildings, store, restrooms, restaurant, etc., are adjacent to a declining blueberry field. In this project, we are attempting to establish a protocol that will allow us to renovate, replant and reestablish an integral field, rebuilding it to once again be a productive part of our operation. I would also like to mention here that each phase of this project has captured the interest of our farm guests and provided an educational opportunity for them to better understand our approach to sustainable farming practices, from cover-cropping to planting. The project has not only generated many questions but it has our repeat customers pulling for our efforts to renovate one of their favorite fields.

There are five components of this project: Field Cleanup, Cover Crops, Preparation of Soil Amendments, Planting and Data collection/Data Analysis.

We have completed four of these primary project components successfully and have had two rounds of data collection and completed analysis for the new field’s first and second growing seasons. As we anticipated, we feel that a second year of data collection has been valuable as trends in data have changed significantly. This change is likely due to the typical nature of the blueberry root growth during the first year in the field. Blueberry roots have a tendency not to grow much out of the existing root ball over the first growing season. We feel that this characteristic minimizes any effect that our soil amendments could have had on first year plant growth. This theory seemed to be validated in the first year by an observed inverse relationship between the growth and vigor of a plant and the application of amendments. While finding that a certain amendment might have a deleterious impact on plant growth or vigor, I felt that we needed an additional growing season to see better what was going on. An alternative explanation might be that soil moisture could have been impacted by the addition of the full complement of soil amendments used. We requested and received an additional unfunded extension for this project through the 2017 growing season, to be completed with the final report completed by December 15th of 2017. In addition, we will also continue Fall data collection over the next 3 years so that we will have a more complete view of the impact of these amendments. This information will be made available in outreach efforts as well in years to come.

Preparation of field for one of four sorghum sudan cover crops.

Our project is progressing well with regard to our objectives. Specifically, objectives achieved include:

1. Field clean-up (Completed July 2012) a. Old plants were removed, including the roots as fully as possible. b. Previous irrigation lines were removed. c. Soil that was previously mounded for the raised beds was distributed over the field so as to expose it to full cover crop treatments and to facilitate cultivation of cover crops and solarization of soil.

2. Cover Cropping a. Sorghum Sudan cover crop (prepped field, planted, chopped up and incorporated by turning in with plow in Springs of 2012, 2013, 2014 & 2015) b. Mustard cover crop (prepared field, planted, chopped up, incorporated and rolled field to maximize bio-fumigative impact (early Spring 2013) (Late crop of Sorghum Sudan was also planted in 2013.) We have used cover cropping since we began our farm in the summer of 1982. We have noticed anecdotally a direct relationship between the number of cover crops a field has had and the health of that field's plants. In that the cost of a field failure would be especially great in blueberries, we spent several years cover cropping to help insure this field's success. The cost benefit of such extensive cover cropping would be valuable in itself.

3. Plants selected, acquired and scheduled to arrive just prior to planting time. We selected the variety Duke as the trial variety, in that it has typically been a strong variety for us and it is an early variety appropriate for planting close to the location where farm guests enter our fields.

4. Preparation of soil amendments (Preparation was necessary to make sure soil amendments/treatments were ready for the time of planting.)

a. Worm casting tea. I attended a composting class which included a vermiculture component, conducted by Dr. Hwei Yiing Li Johnson of Lincoln University. This added to my composting knowledge and aided us in establishing two worm beds for use to inoculate our worm casting tea.

b. Inclusion of worms into planting holes. We planted five worms at each planting site included in the project. We had to first select a variety of worm that would 1) have the desired impact and 2) could function in a blueberry root zone environment. Our research led us to Alabama Jumpers, which are large composting worms that work well in breaking up clay, which is one of our field issues. We tested these worms in soils rich in each of the amendments we were planning on incorporating and found that they did well in a mixture of all the amendments incorporated into soil. Alabama Jumpers were acquired and scheduled to be delivered at planting time.

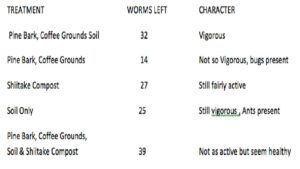

Various media buckets were prepared and 40 worms were placed in each bucket with indicated media to determine if the worms were compatible. They were left for 34 days. The worms seemed most compatible with the full complement of amendments where nearly all of the worms remained in that media bucket.

c. Ground pine bark. We have used pine bark in the past on the farm and have found in a mini study, that we conducted, that it worked as well as sphagnum peat moss as a soil amendment . We located a fence mill that stripped the bark from pine logs and we acquired approximately 40,000 pounds of bark. We ran it through a shredder that produced an amendment with smaller than ¼-inch pieces. This was piled in a conical pile 8 to 10 feet tall. It heated up considerably prior to use but did not fully compost.

d. Composted shiitake logs. In that our farm has a good supply of spent shiitake logs and mushroom compost can be very beneficial in some planting circumstances it made sense for us to reuse this resource. Our own spent shiitake logs were ground up using a rented commercial chipper. This process took a bit over a week and yielded two piles of shiitake log chips that were composted. We monitored the core temperatures of the piles and turned when temperature began declining. We added some nitrogen in the form of urea at a very low rate when we turned the piles as per Dr. Hwei-Yiing Li Johnson.

e. Spent coffee grounds. Several years ago I was approached by a company that had access to significant amounts of spent coffee grounds locally. They asked if I would like to try it as a mulch for our blueberries. We accepted their offer and applied the mulch in the Spring to about 7 to 10 3-year-old plants and realized an increase in the rate of growth of the plants that were mulched with the coffee. Approximately 45,000 lbs. of spent coffee grounds were obtained from a commercial coffee brewing plant that produced iced coffees. These grounds were delivered to the farm and covered prior to incorporation into the soil.

5. Planting was accomplished in The Early Spring of 2016.

a. Field was plowed and disked.

b. A blade was used to throw up the raised beds for planting, as is the Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for planting blueberries at our farm. (Blueberries are planted in raised beds for drainage, preventing the roots from remaining in standing water.)

c. Beds were further cleaned up, smoothed with a drag, and large rocks were removed from the field.

d. Our planting lister/sub-soiler was used to open up a planting trench down the middle of each raised bed

e. We used our mulch wagon to haul and apply coffee grounds, ground pine bark and composted shiitake logs down the middle of each trench, with the exception of row 81, in which we tested each individual amendment separately.

f. Row 81 was laid out so that the first 5 plant spaces were guard plants with no amendments. The next 14 plant spaces were marked for the first amendment, then 5 more guard plants with no amendments, then 14 more for the second amendment and so on. Each amendment trial was marked with a metal stake with it's trial # related below.

#15 Composted Shiitake Logs

#19 Coffee Grounds

#150 Pine Bark

#12 Worm Casting Tea

#155 Earthworm Inclusion

g. A rototiller (approx. 18 inches wide) was used to till in amendments.

h. Irrigation line was laid out in preparation of planting.

i. Plants were spaced at 4-foot intervals in the row this provided each plant with 2 emitters.

j. As a row was completed, irrigation line was fine tuned near the plants and the plants were watered in by turning on the irrigation system.

k. Each row was mulched with hardwood chips, as per farm SOP for planting blueberries.

l. Plants were maintained, as per farm SOP

i. Weekly fertigation -- Not the best situation with young plants the first year but this block was a portion of a mature block that required fertigation.

ii. Weekly foliar fish emulsion.

iii. Irrigated as needed.

6. Data Collection

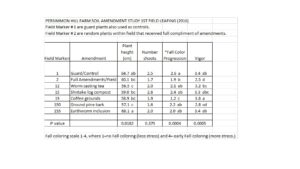

a. Plants were maintained through the growing season and data was collected after the plants became dormant in the Fall of 2016 and 2017. We chose a time for data collection when most plants were well into their Fall coloration.

b. Four data items were collected for each plant in test row 81. We are including data from the guard plants -- the 5 untreated plants between each trial -- as controls. We also recorded the same observations from a random sample of plants from the remainder of the planting that received what we termed full treatments (all amendments, worm inclusion, worm castings tea, ground pine bark, composted shiitake log and spent coffee grounds.)

i. Height of plant measured to its longest cane.

ii. Number of viable new shoots sent up.

iii. Grower interpretation of its vigor, with 1 being least vigorous and 4 being the most vigorous. All observations were made in the same day by the same person, and attempts were made to be consistent in evaluation of all plants.

iv. Fall coloring scale 1 - 4, where 1 = no fall coloring (low stress), and 4 = full fall coloring (relating greater stress)

7. Data analysis was accomplished using SAS software to evaluate the differences among and between individual treatment means, using the 0.05 significance level. SAS assigns one or more subscripts to a treatment mean in order to be able to make such comparisons. If two means have the same letter subscript, then the difference between those two treatments is not statistically different. If two means have different subscript letters, then the difference between the two numbers is statistically significant and the difference is most likely due to a factor other than chance.

After considering the data collected in the Fall of 2016, we decided that in that it was so inconsistent with our expectations, that we should extend the project an additional year prior to submitting the final write-up. This decision was based upon the following:

- Control plants without soil amendments were rated as having higher vigor than the fully amended plants and greater than those whose soil was amended with ground pine bark alone.

- Control plants without soil amendments had longer cane growth than those inoculated with worm tea or amended with ground pine bark.

- Control plants without soil amendments showed less fall color change (a plant stress indicator) than did plants with all amendments.

- Plants whose soil was amended with coffee grounds showed less fall color change than did control plants. (This was the only statistically significant positive effect of any of the soil amendments.)

- There was no statistical difference in the number of shoots produced by plants across all soil amendment categories.

As we compare the various trial groups, it seems important to collect data through an additional growing season because either many of the amendments have had the exact opposite effect than anticipated, or as previously related, the roots have yet to extend out of the root ball far enough for the soil amendments to impact the plant's growth. We greatly appreciate SARE's willingness to prolong this project's data collection phase.

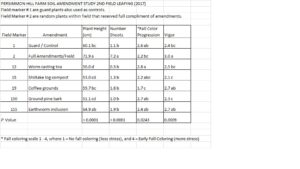

The data collected in the Fall of 2017 showed very different trends than did the first round of Data.

Second year growth (collected Fall of 2017) shows much greater cane growth (height), more new shoots, and a higher vigor for plants that received a full compliment of the soil amendments: Worm casting tea, shiitake log compost, coffee grounds, ground pine bark and earthworm inclusion.

The only variation in this trend was that plants that were amended with only coffee grounds exhibited less stress as indicated by later fall color change than did any other amendment combination. This validated the initial data collected in the Fall of 2016 which also saw less plant stress as related by later fall color change within the plants that received only the coffee grounds soil amendment. These plants exhibited less stress than the plants that received the full compliment of soil amendments.

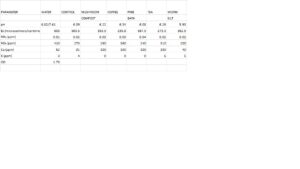

It appears that the combination of amendments either symbiotically adds to the general health of the plants or it could be that each amendment adds to the organic matter in which the plant grows. In this case, plants that received all soil amendments had considerably more organic matter in their root environment than did plants that were amended with single amendments. A soil with high organic matter is a critical component to the health of a blueberry plant. Further study is needed to understand this relationship better.

It is entirely possible that subsequent years could alter our results and we anticipate taking data for several years to monitor potential changes.

Cooperators

- (Educator)

- (Researcher)

- (Researcher)

Research

Through our experience and the experience of other growers we established a reclamation protocol which included the soil amendments selected for the acre of ground we are replanting within this study. The plan called for:

- Field Cleanup which included the removal of old plants as completely as possible, removal of all old irrigation system and the leveling of mounded rows so that cover cropping could be more effective.

- Goal here was to reduce disease reservoir

- Cover Cropping using sorghum sudan as primary cover crop in 2012 through 2015. Mustard (brassica) was used early in 2013 for its fumigative effect to the soil.

- Goal here is to further reduce pathogens and increase organic matter in the planting

- Plants selected Duke 18+" tall in pots.

- Goal here is to select disease free plants of a variety that has proved to be successful in the environment of our farm and fit well with regard to time of ripening in their location on our farm. Have these plants ready on planting date.

- Acquisition and preparation of soil amendments

- Goal here is to acquire pine bark & grind, evaluation and acquisition of proper variety of worm for inclusion, establishment of worm bed as source for inoculation of worm tea including set up of equipment to produce, source and acquire spent coffee grounds and grind shiitake logs and compost to soil. So that all amendments are ready at the same time for use in planting and ready to be tilled into the soil

- Preparation of field for planting

- Goal is to prep irrigation, throw up ridges to plant on, open planting trenches and have crew ready and trained for planting.

- Maintenance of planting through season

- Goal here is to maintain irrigation, weed control, mulch and fertilizer as per our SOP for our farm cultural practices.

- Data collection was conducted. We used 4 dependent variables

- They were selected due to their ease of collection and their ability to provide a good quantitative indicatior of the health of the plants. We used Length of tallest cane, # of new shoots, fall color progression (early Fall color indicated higher stress) and general vigor of plant.

- Analysis of data

- We used SAS software to compare the average values recorded for the various groups of plants that were treated with each soil amendment in order to determine whether the differences were statistically significant.

- Impacts

The data trend that we have seen in this the second year of data collection in this project gives us more confidence in our blueberry field reclamation protocol for our farming operation. We believe that the rather extreme cover cropping that we conducted prior to planting was beneficial in preparing the soil, controlling pathogens and in controlling problem weed species and thus helping to support the new plants in the field.

As a blueberry grower with over 35 years of experience growing blueberries in our Ozarks environment and from the data collected for the second leafing of this field I feel comfortable to say that this new field using this replant protocol is at least as successful at this point as other plantings that we have made in ground new to blueberries. This has significant impact on the future of our operation and information we are ready to share with growers in need of reclaiming fields in their operations.

Venues for sharing info include but are not limited to: Field visits, both formal and informal, The Missouri Blueberry School, meetings of the Arkansas Blueberry growers association, SARE Farmers conferences, Oklahoma Blueberry farmers (informal farm tours) planned by Mike Auxier (owner of Outback Farms) and others as they arise. Now with the trends that we are seeing with this field's success in recovering, it is time to take a more active role in sharing what we are finding. Mr. Patrick Byers, Mr. Andrew Thomas and Dr. Hwei-Yiing Li Johnson (all cooperators in this project) are kept abreast of our findings and all have educational components to their positions. Each will share information with other growers whom they are advising as the need arises.

Accomplishments

We have accomplished the development of a workable protocol for reclaiming a blueberry field into what we anticipate will mature into productive field. This protocol appears to be more successful than those used on our farm in the past and more successful than those used by other regional growers of which we are familiar. As with any research many questions are raised and a number of refinements could be made with further investigation of individual components. We will always use this new protocol for new plantings, individual replants and field reclaimations. Our new protocol includes the following:

- Clean up all parts of all plants tops and roots in the field as well as all irrigation equipment.

- Turn in as many cover crops as time allows including at least one crop of mustard. (We utilized Caliente TM Brand 199.) (Time cutting prior to rain, turn in and roll ground to achieve maximum effectiveness as biofumigant.)

- Amend soil by including Shiitake log compost, coffee grounds, ground pine bark, tilled into planting bed and inclusion of Alabama Jumper earthworms (Amynthus Gracilus) at each planting site. Data seems to indicate that there is a statistically significant symbiotic effect among the combination of all of these amendments that is not evident when used individually.

- Care for plants as per our SOP regarding irrigation, fertigation, foliar feeding and weed control.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation summary:

During the course of this project we have been visited by the local master gardeners program and conducted a full farm tour which included the Blueberry reclamation project. The Missouri Blueberry school class visited our farm previously. In both of these visits the concept of replanting blueberries was discussed. Since we have completed this study we are now in a position to relate our experience and make suggestions based on our experience.

My plan now is to develop a power point presentation to share with other growers when the subject arises.

I have participated in gatherings sponsored by the University of Arkansas Plant Science Dept. There we had discussions on problems with older plantings and the replanting of individual plants and whole fields where necessary.

Learning Outcomes

From this grant we refined our replant/reclamation protocol (based on the success we have experienced to date) to a point that we can more confidently take a field of berries that is not producing well clean it up, cover crop it, amend the soil and return it to what we believe will be satisfactory production.

I believe that we overcame our identified barrier in that we have a mechanism to reclaim fields that were no longer productive. Especially important in fields close to our guest facilities. We did this by way of developing the replant protocol as per above.

The advantages are that important land adjacent to our guest facilities (restrooms, restaurant, gift shop etc.) can be reclaimed and the integrity of our physical operation be maintained. I am not seeing disadvantages other than some additional cost in planting.

If other growers came to me with the concerns similar to the ones we had and addressed through this grant I would refer them to the final report and respond to questions as best I could.

**Item below**(# of growers gaining knowledge from this project is small because we just completed it and now feel confident of our protocol so we have had little time to share more.)

Project Outcomes

As stated previously we have adopted the protocol developed as a result of this grant for reclaiming fields that have lost their vigor for our farm going into the future and the field that we renovated is progressing as well as other fields initiated on new ground. This field was important to us in that it is adjacent to our physical operation and once again provides us with a good field for guests to pick close to our buildings and adjacent to guest services.

An additional question that was brought up by our study was: Just what is the cost benefit ratio of multiple cover crops? In our project we did 4+ cover crops. This could have potentially been an over kill. Our rationale for planting extra cover crops was that we anecdotally observed a relationship between multiple cover crops and a field's success. I believe totally in their benefit but it would be interesting to know the value of multiple cover crops. They take time and have an expense associated with them so refining their cost/benefit would be of value. Might 2 be enough? Such a study would take several years and have some implicit problems in vivo with regard to relating growth data from year to year, making comparisons of cover crop treatments difficult.