Final Report for FW14-012

Project Information

European starlings on dairy barn

European starlings on dairy barn

European starlings are an invasive species in North America

European starlings are an invasive species in North America

The purpose of this study was to examine possibilities for natural predators, primarily native birds of prey, to serve as biocontrols for pest birds and rodents on Washington dairy and berry farms. We estimated bird and rodent damage on dairies in Washington State through farmer surveys; performed bird counts on 10 Whatcom County dairies within <1 mile of fruit crops; implemented measures to enhance the presence of native birds of prey in Whatcom County agricultural areas; introduced and encouraged bird abatement falconry on dairies; worked on youth, farmer, and general public outreach highlighting the ecosystem services of farmland birds; hosted a conference and an on-farm demonstration related to agricultural birds; created and posted an educational video about using native raptors and trained falcons for nuisance bird control; developed and distributed a laminated bird ID card; and successfully collaborated with additional researchers to build a longer-term project as we realized the scope of the problem of European starlings on dairy farms.

Introduction

Wildlife damage to fruit crops in Washington and Oregon has been cost-estimated from $400- $3000/acre/year in grapes, cherries, blueberries and apples (1). With expansion of blueberry acreage in Whatcom County and other western Washington counties over the past decade, dairies are increasingly located adjacent to blueberries. The invasive European starling is responsible for much damage to both fruit and stored dairy grain and forages, but other birds and rodents are also implicated. Though not rigorously examined previously, estimated losses to dairy operations range from $2000-$10,000/herd/year or more with a typical 1,000-bird starling flock easily consuming a ton of silage each month (2).

The pattern for starlings includes roosts at dairies, where high energy foods are available at open faces of bunker silos, in grain rations fed to cows in feeding areas, and in manure lagoons. Starlings on dairies contaminate feed, water, and housing year-round, and eat and contaminate fruit during blueberry season. They also damage silage tarps. Similar patterns may be seen where livestock feeding occurs near other fruit crops (e.g. beef feedlots/dairies near Yakima cherry orchards in eastern Washington).

Rodent problems include rats eating corn and grain on dairies and chewing silage tarps and wiring, and voles chewing roots and bark in fruit crops (3).

Use of scare tactics such as propane cannons and bird distress calls are widely perceived to be ineffective; these measures also disturb farm and non-farm neighbors. Lethal management methods include trapping, shooting, and poisons. Farm employees may have little time or ability to distinguish between "pest" and "beneficial" birds, sometimes using a guiding principle that "the only good bird is a dead bird." Starling and rodent traps can remove individuals but may inadvertently trap beneficial birds such as swallows and raptors, or harm other non-target species. Poisons have potential to move through the food chain, harming beneficial species such as raptors and even domestic cats and dogs (4,5).

The intent of this project was to quantify the extent and impact of bird damage on dairy farms. Using interview and survey tools, we quantified annual feed losses attributable to birds (feed consumption and fecal contamination) and time and money spent on shooting, trapping, poisoning and other techniques. Adjacent blueberry growers were also interviewed about damage.

Several dairies with proximity <1 mile to fruit crops were selected for implementation of ecologically sustainable, biocontrol techniques including installation of barn owl and kestrel falcon nest boxes.

We connected area falconers to dairy owners willing to allow falconers access to their facilities. Placement of carrion (undiseased dairy placentas and stillborn calves) for natural decomposition in sufficiently isolated fields (under Washington State Department of Agriculture regulations) was tested as a means of keeping natural predators in the targeted study area.

Cessation of rodenticide use was requested on participating dairies to minimize risk of secondary poisoning or trapping of raptors. Dairy owners and employees were provided with bird identification instruction to prevent shooting of beneficial and non-target species. We also encouraged adjacent fruit growers to discontinue rodenticide use and shooting of non-target birds.

Bird counts were taken at each of the chosen dairy field sites. Each dairy farmer was asked to estimate damage levels and perceptions of effectiveness of the various techniques attempted. Based on these numbers (pest counts, farmer estimates of damage, and farmer perception of effectiveness), a few techniques were selected for highlighting at a conference and a demonstration event to which area dairy producers were invited.

Area 4-H and FFA youth helped with this project by meeting with falconers and installing kestrel falcon nest boxes. Additional outreach included presentations and emails to Washington State Dairy Federation (WSDF) members; presentations to dairy farmers at two Whatcom Conservation District (WCD) annual workshops; presentations to scientists, farmers, and other agricultural employees at conferences; articles on the Washington State University (WSU) Extension webpage; an educational nest box webcam; a native raptor and falconry video posted on WSU and Whatcom Family Farmers (WFF) websites; bird and wildlife stations at several agriculture education events; and a bird identification card distributed to farmers, rural landowners, and other citizens.

The scope of the problem was so much greater than anticipated that a second and larger WSARE Research and Education grant project was created to measure bird impacts on cow welfare. This project is now successfully underway in conjunction with WSU and USDA/APHIS collaborators.

The expectation of this Farmer-Rancher WSARE project was that enhancement of habitat for birds of prey, or other means of providing "natural" controls for pest birds and rodents, could prove economically beneficial for farmers, while reducing direct and indirect mortality of raptors and other beneficial species (6,7). Farmers were able to envision economic benefits of native raptors and biocontrols, increase public perception of the value of agriculture for wildlife species, and improve the overall quality of rural community life through these efforts.

1. Anderson et al 2013. Bird damage to select fruit crops: The cost of damage and the benefits of control in five states. Crop Protection 52:103-109.

2. Johnston 2013. Coping with sky-high feed. Successful Farming (Nov):BI1-2.

3. Ashkam 1988. A two-year study of the physical and economic impact of voles on mixed maturity apple orchards in the Pacific Northwestern US. Proceedings Vertebrate Pest Conference 13:151-155.

4. Rattner et al. 2011. Acute toxicity, histopathology, and coagulopathy in American kestrels following administration of the rodenticide diphacinone. Environmental Toxicology & Chemistry 30:1213-1222.

5. Thomas et al. 2011. Second generation anticoagulant rodenticides in predatory birds: Probabilistic characterisation of toxic liver concentrations and implications for predatory bird populations in Canada. Environmental International 37:914-920.

6. Baldwin et al. 2014. Perceived damage and areas of needed research for wildlife pests of California agriculture. Integrative Zoology 9:265-279.

7. Steensma et al. 2016. Bird damage to fruit crops: a comparison of several deterrent techniques. Proceedings Vertebrate Pest Conference 27:xx-xx (in press).

Original objectives of the project proposal / measured performance:

- Estimate bird/rodent damage to dairies through farmer surveys. About 22% of Whatcom County dairies, and about 21% of surveyed dairies across the state, responded to the survey. Of respondents, 98% indicated birds were a problem on their farm(s) and 49% indicated rodents as at least a slight problem.

- Measure numbers of pest birds and rodents at dairies and adjacent fruit fields through field data collection. Bird counts were conducted at 10 Whatcom County dairies over 2 seasons. Numbers ranged from 100-4,000/dairy/day at peak times. Rodents were not counted directly.

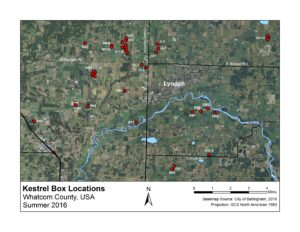

- Implement bio-control methods for managing problem birds and rodents in dairies/adjacent fruit. In Whatcom County: Kestrel falcon nest boxes were installed/maintained at 38 sites; owl nest boxes were monitored at 3 sites; and carrion feeding stations were established at 2 sites.

- Estimate any changes in pest damage levels and raptor presence resulting from project implementation. In Whatcom County: Kestrel box occupancy was 5-10%; owl box occupancy was 66%; and carrion feeding drew eagles and turkey vultures each time carrion was placed, but these raptors were transient. The limited duration of the raptor enhancement project prevented accurate estimates of changes in pest damage levels.

- Host demonstration days at dairies. A falconry and raptor nest box demonstration was hosted at a Whatcom County dairy in fall 2015. This demonstration, along with additional similar demonstrations targeted to youth and adults through various events in 2015-2016, educated at least 1,200 people, including at least 300 directly employed in agriculture. Additionally a “virtual demonstration” by means of a video link about birds on dairies reached 1,200 views within a week of being posted online.

Cooperators

Research

- Estimate bird/rodent damage to dairies through farmer surveys

Six Whatcom County dairy farmers and 2 berry farmers were interviewed in 2014 to determine their perception of bird and rodent damage on their farms. Based on these interviews, we designed a one-sheet survey that was distributed at the November 2014 WSDF annual meeting in Clark County, and again at a WCD/WSU dairy workshop in January 2015 in Whatcom County. Additionally, an invitation to participate in an electronic version of the survey was distributed by WSDF in December 2014 to all dairy farmers in the state with an email address in the WSDF database, which totalled 250 email addresses (more than half of the 430 dairies registered in the state at that time). We received a total of 53 responses, which represented 21.2% of the 250 dairies with email addresses. Within Whatcom County, the response rate was slightly higher at 22%.

The survey had questions regarding basic farm parameters (herd size, acreage, crops, adjacent fruit acreage, feeding technique), perceived losses due to birds and rodents, history of pest control practices on the farm, and perceived effectiveness of various deterrent techniques.

Cows competing with starlings for feed at the feed bunk

Cows competing with starlings for feed at the feed bunk  Starling night roost at a dairy

Starling night roost at a dairy

- Measure numbers of pest birds and rodents at dairies and adjacent fruit fields through field data collection

Based on reported farmer observations, the European starling count increases in autumn and peaks in winter. Thus we modified our counting protocol to focus on the fall transition season and made initial counts at two farms throughout November 2014. Bird numbers quickly increased as the weather cooled. The scale of the problem was most evident where thousands of European starlings were roosting each night in dairy barn rafters, defecating throughout the barns and competing directly with cows for feed in feed bunks.

Through an interview process we chose 8 additional dairies spread throughout Whatcom County on which to conduct an earlier and more thorough set of bird counts in September and October 2016. All 10 dairies had known European starling populations, were willing to allow us access to their farm(s), and provided background information on their practices.

In 2016, we conducted intensive bird counts at all 10 sites as corn harvest was occurring and nighttime temperatures were cooling. Counts were made by visiting dairies twice per day, at least once per week, for at least 4 weeks. The researcher drove to a previously-selected viewpoint and remained in a car, using the car as a “blind” because birds tend to be more reactive to a person on foot than to a vehicle. Counts consisting of more than two dozen birds were estimates, made by viewing roosting spots, counting a fraction of the birds present, and then extrapolating based on the total area of the roost. The researcher spent 20-30 minutes onsite during each counting period. Counting visits were initially timed within two hours of sunrise and sunset at each dairy, but as it became apparent that some dairies had a different pattern in which birds visited temporarily at various times during mid-day, some mid-day counts were added at these dairies.

Birds other than European starlings, such as pigeons and Eurasian doves, were also noted and estimated, and raptors in the visual perimeter of the researcher were noted.

Though not insignificant, rodents were not perceived to be as much of a problem as birds by about half of dairy farmers according to our interviews and the survey. Although 49% of responding dairies indicated anywhere from a slight-to-serious problem with rodents, only about 26% of respondents listed a problem in the $1000/year or more range. For that reason, and due to logistics of rodent trapping, rodents were not counted. Many dairy operators felt that their barn cats kept rodents under control, and this appeared to be the case in our visits. However, at least one of the 10 dairy farmers participating in our bird count field data collection admitted to recent use of over-the-counter anticoagulant rodenticide due to a rat problem. Tragically, a neighboring farm cat known to be an excellent rat catcher ate one of these poisoned rats during the data collection period and became ill. Unfortunately, this cat was beyond hope of successful treatment and was euthanized by a veterinarian. The veterinarian performed a post-mortem that indicated internal bleeding as a cause of illness. Toxicology tests on liver tissue from the cat performed by the Washington Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory and the Michigan State University toxicology lab included a detailed anticoagulant scan to identify the specific fatal toxicant. An ingredient in a common over-the-counter rodenticide was identified and cited as the cause of death.

- Implement bio-control methods for managing problem birds and rodents in dairies/adjacent fruit

Dave Timmer placing kestrel nest box

Kestrel falcon in Whatcom County cherry tree

Kestrel falcon in Whatcom County cherry tree

Pair of kestrels atop a nest box

Pair of kestrels atop a nest box

Kestrel falcon nest boxes: In late spring/early summer 2014, we visited dairies in the two most dairy-intensive areas of the state (Whatcom County and Yakima County) to ascertain the feasibility of kestrel falcon nest boxes in those regions. Yakima County has more total dairy cattle and also had many kestrel nest boxes already in place, particularly in fruit orchards. The eastern side of the state generally has a far higher kestrel population than the western half.

There are more individual dairy farms on the west side of the state in Whatcom County than in Yakima County, but far fewer kestrel falcon nest boxes. Kestrel falcons have been in low numbers overall or in decline for at least two decades in Whatcom County. We therefore decided to focus on Whatcom County for implementing the nest box effort. Boxes were located in either dairy or berry farm areas, but usually in proximity to both. Some of the existing boxes dated back nearly 10 years and were in disrepair. We purchased enough new boxes and rebuilt, repaired, and relocated enough existing boxes in the county to reach 38 functional boxes by late summer of 2016.

GPS points were taken for each box and a map was created showing locations. Boxes were monitored in summer 2014, 2015, and 2016 to determine what species, if any, were present in the boxes. Kestrel counts were anecdotal in Whatcom County for other times of the year.

Note: although a translocation permit for orphaned falcons was in place during 2014-2015, no orphaned falcons became available for translocation from the east side of the state to the west side, so that enhancement possibility could not be pursued.

Barn owl nest boxes: In 2014, 2015, and 2016 we also monitored three owl boxes already in place on dairies. One of the successful owl boxes had a location with accessible Wi-Fi, so in 2014-2015 we installed a nestcam with live streaming on a web site for the public. This webcam was online for several weeks and owls with young owlets were present. The focal length of the camera lens was too close, however, so the visual was limited to close-ups of feathers. Eventually the owls ripped the wiring loose so that the camera shut down. We did not re-build the camera set up because we ran out of time and funding.

Hawk kites: Analysis of other data from a fruit damage study (see citation 7, Introduction) indicated this technique might only be minimally effective, so we did not implement it due to lower priority.

Raptor perches: All dairy farms working with us on bird counts had adequate raptor perches in the form of trees, dead snag trees, and/or utility poles already present so we did not need to install perches.

Carrion feeding station (carcass lower right) attracting bald eagles (in trees on left)

Carrion feeding station (carcass lower right) attracting bald eagles (in trees on left)

Carrion feeding: Over a period of four weeks in November and December 2014 and 2015, we placed stillborn calf carcasses and placentas within ½ mile of two dairy barns with starling populations to test for attraction of large raptors such as bald eagles and turkey vultures to the decomposing material. We counted raptors and watched for any subsequent effects of raptor presence on the starling populations.

Master falconer Tony Lapsansky with bird abatement falcon

Master falconer Tony Lapsansky with bird abatement falcon

Falconry. We obtained the cooperation of a commercial bird abatement falconer in flying his falcon at a dairy barn during fall 2015. Although starlings were not present on that date, we did see the effect of the falcon on pigeons that were present. A professional videographer filmed the event to include in a “virtual demonstration” video. Several dairy families were present at this demonstration. We conversed with the falconer on ideas for use of trained raptors in the dairy farm setting, and also on potential net-exclusion techniques that could be implemented in the future on barns that can be completely closed off as starling nighttime roosts.

- Estimate any changes in pest damage levels and raptor presence resulting from project implementation

In November and December 2016 we interviewed the 10 participating dairy farmers regarding perception of value/effectiveness of various biocontrols. We noted that in the worst starling depredation cases, further data would have to await the larger WSARE-funded project. Bird count data collected on these farms was compared for days on which raptors were seen in the vicinity, to days when raptors were not seen. We also interviewed attendees of the WCD Animal Health Dairy Workshop in November 2016 to gain their perceptions of biocontrol effectiveness.

- Host demonstration day at dairy

In September 2015 we invited farmers to a conference and subsequent demonstration (see 3 above) to view nest boxes and falconry, and discuss the overall pest bird problem. The demonstration of falconry and overall discussion centered on various low cost beneficial techniques for raptor enhancement.

To reach a broader audience beyond the demonstration day attendees, we also employed a professional videographer to create a video depicting bird problems on dairies and showing the potential benefits of kestrel falcon nest boxes, owl nest boxes, and professional falconry. This was posted on both WSU and WFF websites, including the WFF Facebook page, in January 2017.

Additionally, throughout 2015-2016, raptor demonstrations and presentations were held for 4-H groups, Ferndale Middle School and High School classrooms (including an “at-risk” group of students), Lynden High School and Lynden Christian High School FFA classes, two elementary school field trips, other agricultural events, and at the Northwest Washington Fair.

Personnel

Prof. Karen Steensma, Trinity Western University and Steensma Dairy, spearheaded the project, wrote reports, and made multiple presentations. Dr. Susan Kerr, Washington State University, served as technical advisor and veterinary advisor, and assisted with reports, presentations, survey design and hosting, and organization. Mr. Dave Timmer, natural resources biologist, and Mr. Tony Lapsansky, master falconer and bird biologist, helped investigate initial bird issues in Whatcom County and make presentations. Mr. Brian Garries, biologist, helped with data collection, GIS map creation, interactive presentations, and data analysis. Ms. Deanna Leigh, bird biologist, whose MS thesis was on effectiveness of kestrel falcons in cherry orchards, assisted with data analysis and mapping for the project. Mr. Ben Steensma, AA Mechatronics, was hired to assist with kestrel box installation and repair work and recording GPS points of nest boxes. Ms. Kira Banner and Ms. Joy Marconato, 4th year Biology/Environmental Studies majors at TWU, assisted in interactive educational events by wearing a bald eagle costume and using bird puppets to discuss farmland birds with children and adults. Ms. Dina Roberts, 3rd year Environmental Studies major at TWU, helped with data collection. Ms. Ellie Steensma, 2nd year Agriculture Education major at Dordt College, helped with data collection, design and production of the laminated bird identification cards, interactive presentations, and bookkeeping. Mr. Brad Felger, professional bird abatement falconer / owner of Airstrike Bird Control, demonstrated falconry at the Lynden High School FFA Barn and at a local dairy.

- Bird-rodent damage survey. Survey results included a number of interesting trends:

- Nearly all dairy producers responding (98%) indicated bird problems

- Many farmers responding to the initial survey indicated only little to moderate confidence in identifying all the bird species present on their farms

- Of those providing a loss estimate, most farms estimated bird damage levels between $1,000-2,000/year

- Nine farms estimated bird damage at $20,000/year or higher

- One farm estimated damage as high as $200,000/year

- European starlings were by far the top pest bird, with pigeons second

- Sparrows and waterfowl (primarily geese) were critical problems for a few producers

- USDA Wildlife Services trapping was rated "most effective" by a number of producers , but also "not" and "somewhat effective" by many producers

- Shooting was used by the greatest number of producers but was largely seen as only "somewhat effective"

- Only 4 producers listed raptor enhancements as something they were already attempting, and only one of those listed this as the "most effective" method

- Bird numbers tended to show a positive correlation with number of cattle on dairies

- The largest bird population estimates (greater than 50,000 birds) included a dairy with 7,000 milking cows and two dairies between 500-1,200 milking cows

- Rodent damage was noted as an issue by about 49% of respondents, with about 26% estimating damage above $1,000/year and 17% estimating damage of $5,000/year or more

- Bird counts in Whatcom County. November 2014 bird counts on two dairies showed a pattern of one dairy with up to 275 birds, primarily starlings, each morning but not roosting overnight, and a second dairy with an estimated 4,000 starlings consistently present morning and night with an established night roost in the free stall barn. Only a tiny number of additional pest bird species were present at this second dairy. September-October 2016 counts on 10 dairies showed a range of 100-4,000 starlings per dairy per day, with numbers building significantly over the course of the study as temperatures cooled and silage harvest occurred. Combined attractions of both shelter and high energy feed on dairies contributed to the seasonal bird problem for producers, with some dairies showing establishment of winter night roosts during this time period.

- Biocontrol implementation.

Kestrel falcon nest boxes. Kestrels begin courtship, mating, and nest choice in early spring. At the start of the project in 2014, only about 20 existing kestrel nest boxes in Whatcom County were functional, and 2 appeared to be occupied by kestrels that year, for a success rate of 10%. Numbers were similar the following year. Nest box repair, relocation, and new installations brought the Whatcom County total to 38 functional, mapped boxes by late summer of 2016. Unfortunately a lack of labor force in the critical nesting period earlier in that year delayed box checking until post-fledging, so it was difficult to determine whether additional kestrels had been present. In all years, at least 15-20% of boxes showed starling activity. Property owners were encouraged to monitor and prevent starling nests in their nest boxes.

Kestrel box locations in Whatcom County as of summer 2016. Boxes placed by 4H and FFA youth are not included.

Kestrel box locations in Whatcom County as of summer 2016. Boxes placed by 4H and FFA youth are not included.

Barn owl nest boxes. Of three existing owl boxes that were monitored, two were successful each year of the study, for a rate of 66%. The barn owl nest box with the camera installation also received 375 online views during the time the camera was active. The third box had been successful for at least a decade, but owls disappeared around the time neighboring land use switched to blueberries with extensive rodenticide placements. This was also near the location of the rodenticide-poisoned cat, which was confirmed to have toxic levels of diphacinone at 2.0 ppm in the liver attributable to use of rodenticide by a neighboring dairy frequented by this cat. Diphacinone is an ingredient in over-the-counter rodent poisons widely available in retail stores, and not requiring a pesticide applicator license. Cats, as domesticated animals serving in top predator roles similar to owls, might be expected to suffer similar mortality rates when eating poisoned rodents. The story of this incident was relayed to attendees at the November 2016 WCD presentation, as well as in other presentations, as an example of the food-chain issue with rodenticides.

Tubes used for placement of anticoagulant rodenticide in blueberry fields

Tubes used for placement of anticoagulant rodenticide in blueberry fields

Carrion feeding. At the two farms conducting trials of carrion placement to attract large raptors, the placement always attracted bald eagles within 24 hours of placement. Up to 8-10 eagles at a time would eat and dismantle a carcass. Different patterns were noted at the two dairies. At the first dairy, which has long disposed of stillborn calves in this manner, and was a smaller herd, starlings were a minimal problem (fewer than 2 dozen birds). It is possible that long-term, regular presence of eagles may have been part of the reason for the low starling numbers. At the second, larger dairy, which had never previously attempted the carrion technique, there were large flocks of starlings (up to 4,000 birds) with an established nighttime roost. Eagles kept the starlings at this dairy flocking and “nervous”, and may have at least temporarily lowered their numbers. However, depending on the size of the carrion, the eagles often stayed around for only 3-4 days and then dispersed. Starlings with a strong pattern of night roost might be much harder to dissuade from their established roost, especially by a raptor not focused on them.

Falconry. The professional bird abatement falconer who helped with presentations at the schools and participated in the demonstration day was able to show dispersal of pigeons from the roof of a dairy barn and a high school FFA barn during demonstrations. He has been successful in preventing establishment of bird foraging patterns in fruit crops as well. Although the price of using such a technique may be high, for farms needing to prevent establishment of night roosts in the fall, the cost effectiveness of this technique could be worth pursuing.

Brad Felger demonstrating bird abatement falconry to FFA students, Lynden High School

Brad Felger demonstrating bird abatement falconry to FFA students, Lynden High School

- Changes in bird damage and/or raptor presence resulting from this project. Ongoing efforts to improve kestrel falcon numbers through provision of nest boxes were supported, although occupancy rates were low. Anecdotally, kestrel falcons were seen in the county in larger numbers during the years of the study in comparison to the previous decades of decline. Attempts to confirm this information through comparison of citizen data through Christmas Day bird counts and other large datasets are being pursued. Similarly, barn owl box data have been gathered for 20 years by local citizen volunteers and could be used to pursue greater understanding of their numbers in the region. Bald eagles have been increasing for years and their winter use of Whatcom County habitat coincides with a need for starling deterrence; their ability to co-exist with starlings may not make them an ideal candidate for serious decreases in starling numbers, however. From the data taken at the 10 farms in fall 2016, there was definite indication that presence of raptors in general (eagles, red tail hawks, Cooper’s hawks, or other birds of prey) seemed to be related to lower numbers of European starlings. Producers interviewed at the November 2016 WCD meeting reported kestrel falcon and Cooper’s hawk presence in particular helped deter birds from their farms. Gaining consistent presence of these species, however, was seen as a challenge. Berry growers interviewed at the Washington Small Fruit Conference in December 2016 likewise indicated that native raptors, although helpful when present, were not reliable as the sole technique of pest bird deterrence. All berry growers interviewed agreed that use of professional bird abatement falconry was the best deterrent technique, although expensive.

- Demonstration day and video. The dairy demonstration day featuring falconry attracted 9 members of dairy farm families, representing 4 farms in total, who were impressed with the potential for falconry but concerned about potential cost. All stated support for native raptor nest box efforts as a low-cost enhancement, as long as there was monitoring and maintenance of kestrel boxes to prevent possible starling use when kestrels fail to occupy the box. Other presentations to youth, adults, and non-farm citizens reached an estimated 1,200 people with an in-person message and/or training regarding the value of native birds and the value of agricultural land. The video highlighting nest boxes and falconry reached an additional 1,200 views within one week of online posting on the WFF Facebook page and WSU website, and only positive comments were posted by viewers.

Research outcomes

Education and Outreach

Participation summary:

Ellie Steensma (far left) interacts with visitors to farmland bird display at 2016 Northwest Washington Fair in Lynden

Ellie Steensma (far left) interacts with visitors to farmland bird display at 2016 Northwest Washington Fair in Lynden

Brian Garries demonstrates eagle kite at 2016 NWWF display. Washington Farmland Birds poster and kestrel nest box are seen in the background.

Brian Garries demonstrates eagle kite at 2016 NWWF display. Washington Farmland Birds poster and kestrel nest box are seen in the background.

Kira Banner using eagle costume at 2016 NWWF bird display to interact with fairgoers

Kira Banner using eagle costume at 2016 NWWF bird display to interact with fairgoers

WFF Wildlife on Farms Station Plan

FFA presentation - 1st slide only

Online publicity for WCD presentation. Dairy farmers also received emails and postcards in the mail publicizing this workshop.

Online publicity for WCD presentation. Dairy farmers also received emails and postcards in the mail publicizing this workshop.

http://whatcom.wsu.edu/wam/jun15_s2.html

Birds on Dairies Survey article- Vet Med newsletter submission final

- Producer outreach. Whatcom County dairy farmers were involved in this project from beginning to end. We interviewed a few fellow producers initially and then performed surveys targeting all dairy producers in the state via direct presentation and online solicitation through WSDF; both avenues provided initial outreach on the project. A research update was provided through the WSU Extension website and educational events. Posters relating to raptors as pest control were presented at the Washington Small Fruit Conference in 2014, 2015 and 2016. We also created a one-page laminated weatherproof bird identification card for farm owners, employees, families and the public distinguishing agriculturally beneficial birds from pest birds. We hosted a demonstration field day for area producers to see and discuss the project. We presented a poster of the project and distributed bird ID cards at the November 2016 WSDF meeting in Ellensburg and at the December 2016 Washington Small Fruit meeting in Lynden.

- Youth outreach. We communicated to area 4-H leaders and FFA advisors at county high schools through personal phone calls to set up presentations. We recruited youth involvement by offering nest box building plans and box placement information and monitoring instructions for their own use. Nest box construction and sale was encouraged as a group fundraising activity. At least three privately built falcon nest boxes were placed because of this effort. We also presented in-person, interactive information about bird/wildlife habitat on farms to a total of 400 elementary students in Whatcom County during the WFF Whatcom Farm Circle event in October 2016, to 175 elementary students during field trips to Tennant Lake boardwalk in May 2015 and May 2016, and to at least 300 children accompanying their families to the Ag Adventure Center at the Northwest Washington Fair in August 2016. Several undergraduate college students in related fields helped collect and analyze data, design publications, and present information to other youth and to the public.

- Public outreach. We communicated to the public and the broader agriculture community via newsletters, social media, and press releases to local media. The recently posted video of falcon activity on dairy farms has already proven popular with the public. We will also continue to communicate with the public through the WSU Extension website and provide copies of our project summary sheet and nest box building plans for distribution through WSU Extension, WFF, the Northwest Washington Fair, and other locations.

We were able to measure success of our educational outreach by noting the following metrics:

Educational materials produced and distributed:

- Pre-research summary and survey explaining the project (400)

- Post-research summary with results of study distributed to participants (10)

- Laminated, double-sided farmland bird identification card (600)

- Project website through WSU including summaries of the project, details of research, and recommendations relating to biocontrol of pest birds and rodents

- Website pages with video of the project hosted by WSU and WFF (1,200 views)

- Posters, PowerPoint presentations, and interactive displays at four dairy and fruit industry meetings

- One 4-H, two FFA, one at-risk high school class, two middle school classes, and 14 different elementary classes reached though field trips, events, and other agricultural venues including the Northwest Washington Fair.

Education and Outreach Outcomes

Potential Contributions

The problem of pest birds on dairies was much larger, and far more serious in its implications, than we had expected when making this initial project proposal. Although all final outcomes of the project remain to be seen, there is greater knowledge of the project, and of beneficial raptors in general, amongst the Whatcom County farming community and likely statewide as well. Other farmers have contacted us for further information or nest box placement information because they heard about it from another farmer. The WFF organization, a non-profit group representing dairy, berry and other farmers in the county, has embraced the idea of farms as providers of wildlife habitat and is actively promoting raptor enhancement as part of their educational outreach.

The project fulfilled sustainable agriculture relevance as defined by Western SARE under these three categories:

- Economically viable. Natural raptor enhancement requires little or no cost to implement or maintain and reduces costs of pest damage and pest management.

- Environmentally sound. Natural raptor enhancement helps native species that have been in decline, such as barn owls and kestrel falcons, by providing habitat for them and reducing practices that actively harm them, such as rodenticides and shooting.

- Socially responsible. Natural raptor enhancement in the place of propane cannons, rodenticides, and shooting helps native species while improving the quality of life of farmers, employees, and non-farm neighbors and helps decrease food safety risks.

Specifically, this project contributed to sustainable agriculture in several ways:

- Initial interviews and the survey raised awareness of sustainable approaches. The initial investigation with dairy farmers and the interaction with adjacent fruit growers raised awareness of economic impacts of wildlife damage and ecological damage of toxics, trapping, and indiscriminate shooting, while also introducing these farmers to possibilities of an ecologically-sustainable set of biocontrols that could work for two different commodity groups.

- Estimates of bird and rodent damage provided information about agricultural food chain interactions. By estimating pest numbers themselves and allowing the counting of birds on their farms, participating farmers gained greater awareness of various species present, including beneficial species such as owls, hawks, falcons, and swallows.

- Introduction of biocontrol methods encouraging raptors has allowed farmers to consider ways of working with nature in a more sustainable system. Placing nest boxes, recognizing raptor perches, allowing falconry on their land, and making other efforts to encourage natural checks and balances for pest populations helped participants gain awareness of positive actions to increase ecological sustainability of their farms.

- Perceived economic value of biocontrol methods has encouraged the concept of “economic sustainability = ecological sustainability.” Though measurements of large economic benefits were outside the scope of this project, if farmers determine they saved time and money while contributing to ecological agriculture, even if this simply means decreased reliance on rodenticides or less time spent driving an ATV and shooting, or less time setting traps, they will view this as a sustainable practice.

- Youth involvement has raised awareness of sustainable pest control practices with the next generation. Explaining the principles of biocontrol and providing hands-on opportunities for 4-H and FFA youth to be involved in this project through nest box monitoring and falconry observation has planted the idea in young minds of an integrated pest management approach that is economically, socially, and ecologically beneficial. Undergraduate students in biology, environmental studies, agriculture, and mechatronics also gained knowledge, skills and experience in helping to collect and analyze data, design publications, and present information in public settings.

- Positive interaction with neighboring farmers has contributed to a strengthened agricultural community. Willingness to understand the complexities of wildlife in a varied agricultural landscape, cooperate with neighboring farmers, and show consideration for other farmers’ needs has strengthened the mutual respect needed for a diverse agricultural industry to survive and thrive in our region.

- Public awareness and outreach has raised awareness of the value of farmland in providing habitat for birds in particular, and for wildlife in general. Outreach with youth at the bird/wildlife station of the WFF-WSU Whatcom Farm Circle field trip in Lynden reached 400 elementary students and 100 adults with the message of farms as good habitat for birds and wildlife. Further field trips in 2015 and 2016 with 175 elementary students at Tennant Lake boardwalk provided similar information on bird habitat needs and the inter-connection of farmland and wildlife. Additionally, the farmland birds display and interaction with adults and children over the six days of the 2016 Northwest Washington Fair in Lynden resulted in conversations with at least 300 people, distribution of 100 farm-wildlife coloring books, and countless other viewers (total fair attendance was 184,000 people).

- Interaction with non-farm neighbors has been strengthened. Farmers have shown consideration for non-farm neighbors and the greater community by avoiding use of guns, loud propane cannons and bird distress calls, while encouraging aspects of nature most people find aesthetically pleasing and enjoyable, such as increased presence of raptors. Resulting support for agriculture within the rural community should increase.

- Interaction with bird-watchers and the environmental community has potentially been improved. To keep agriculture viable, farmers must increasingly prove the ecological sustainability of farms and even defend against those who do not understand or value agriculture, especially animal agriculture. The impression that ecological principles can be accepted and even embraced by conventional as well as organic farmers needs to be promoted. This will improve the public image of farmers across a broad audience.

- Viability of value-added or niche marketing could be enhanced through this project. When consumers are given the choice, they will choose fruit products that promote falconry and nest boxes as bird deterrent techniques over products in which bird deterrence involves toxins, trapping or shooting (8). This may be true for dairy products as well. The value of small independent dairies, as well as larger cooperatives’ brands, could be likely enhanced at least 10% by publicity related to this project. Additionally, eco-tourists and agri-tourists would find this raptor enhancement work appealing which could support a growing agriculture niche market.

- Potential protection of agricultural land use in the face of urbanization. Whatcom County, and western Washington counties in general, are facing unprecedented pressure from urban sprawl. If this type of project can improve appreciation and support for agriculture, it may ultimately help protect farmland from sprawl by making a case for the "ecosystem services" provided by healthy and diverse farms.

(8) Herrnstadt 2013. Consumer Reactions to Bird Management Practices on Fruit Crops, Research Brief, Department of Community Sustainability, Michigan State University

Future Recommendations

One of the biggest outcomes of this project was the additional support of two more researchers, Dr. Adams-Progar of WSU and Dr. Shwiff of USDA/APHIS, who visited the area, participated in the producer meeting and demonstration day, and subsequently worked with us to create a new research proposal subsequently funded by WSARE.

Future recommendations coming from this Farmer-Rancher WSARE include topics which will now be studied by the larger Research and Education WSARE:

- Study disease transmission issues associated with bird activity on farms.

- Investigate effect of nuisance birds on cow welfare

- Quantify impact of nuisance bird activity on dairy cow ration (formulated vs. actual) and subsequent effect on health and production

- Determine efficacy of bird deterrent methods such as exclusion netting, trained falcons, and drones

- Continue to promote awareness of positive aspects of native raptor enhancement and of dangers of rodenticide.

We are encouraged by the enthusiasm of the WFF organization and nearly every berry and dairy producer we have met locally to assist us with promoting natural predators as pest biocontrol agents. WSU, WCD, and the WSDF will continue to assist us in disseminating results statewide.