Final report for FW18-039

Project Information

Our first objective was to determine the influence on feed efficiency and whole-season productivity in pastured laying hens of feed (1) Hydration; and (2) Fermentation, relative to feeding dry mash. Our second objective was to carry out an economic analysis of different feeding systems using our field data and market data, in order to help other farmers assess the potential value of feed hydration or fermentation in their own production system, given the extra labor requirements.

Cooperators

- - Technical Advisor (Researcher)

Research

All diets in this study were prepared from the same complete mixed ration, a whole-grain mash (Naturally Free Organic Layer, 16% protein, from Scratch and Peck Feeds). The diets and their preparation methods were:

1. Dry feed, presented to the birds as-is;

2. Hydrated feed, soaked in water at a ratio of 3.2 parts feed to 3.3 parts water just prior to feeding;

3. Fermented feed, soaked in water at a ratio of 3.2 parts feed to 4 parts water for 48 h prior to feeding.

The birds used for the study were Golden Sexlink laying hens. One hundred chicks arrived at Foothills Farm on 10 Oct 2018, at one day of age. They were brooded together and fed with dry feed. At 13 weeks, the birds were transitioned to pasture. At 16 weeks, on 30 Jan 2019, feeding of the experimental diets began.

The birds were separated into nine experimental groups. One group consisted of ten hens in a pasture house. Each pasture house was assigned to be fed with Dry, Fermented or Hydrated feed. There were three houses (replicates) assigned to each type of feed. The houses were arranged in a 3 x 3 grid with each feed type represented once in each row and each column, i.e., a Latin Square design (see photo).

A predetermined weight of feed was delivered to each house daily. At weekly or two-week intervals, leftover feed was collected and weighed, allowing the calculation of feed consumed during that period. Hens had access to drinking water ad libitum. Eggs were collected and counted daily. Between June and October 2019, on nine occasions, a sample of eggs was collected from each house and weighed to estimate egg size in each treatment. Feed and egg measurements reported in this document were taken between 3 Mar and 10 Oct 2019.

Data were analyzed statistically using linear mixed-effects models with Diet as a fixed effect and row and column of the pasture-house grid as random effects. The threshold for determining statistical significance of diet overall and of pairwise differences between diets was alpha = 0.05.

The full text of results and discussion are in the attached trial report, including text and figures.

Foothills Farm study_Full report

Statistically significant results from the data collection period 3 Mar - 9 Oct can be summarized as follows (feed data are dry-basis):

- Dry-diet birds reached full production (0.8 eggs per bird per day) soonest, at 153 days vs 164 days for Fermented-diet birds and 167 days for the hydrated diet.

- Fermented- and Dry-diet birds sustained full production longer than Hydrated-diet birds. Fermented-diet birds spent 155 days at full production; Dry-diet birds, 125 days; Hydrated-diet birds, 92 days.

- In the summer and fall, Fermented-diet birds produced significantly more eggs per hen-day-1 than either Dry- or Hydrated-diet birds. Hydrated-diet birds produced significantly fewer eggs per hen-day-1 than Dry-diet birds.

- While birds on Fermented and Dry diets produced eggs of similar weight over the course of the year, birds on the Hydrated diet produced significantly heavier eggs (71.6 g vs 69.3 g for Fermented and 68.4 g for Dry). Throughout the experiment, all eggs sampled for weighing could be classified as USDA Extra Large.

- Feed consumption tended to be lowest in the Hydrated-diet groups through the year. In fall, feed consumption was significantly greater in Dry-diet birds (159 g per day) than in Fermented- (144 g dry basis) or Hydrated-diet birds (136 g dry basis).

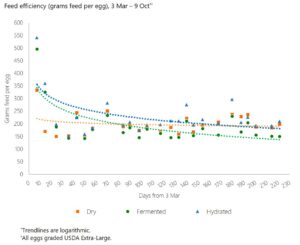

- Feed per egg values were significantly less for Fermented-diet birds than for other groups in summer and fall (174 g per egg for Fermented-diet birds in summer vs 196 g for Dry and 221 g for Hydrated; 163 g per egg for Fermented-diet birds in fall vs 207 for Dry and 206 for Hydrated). See the feed efficiency graph.

A graph of feed per egg (y) over time for birds fed Dry, Hydrated and Fermented diets. All feed values are dry-basis. - In the economic analysis, greater egg revenues from the Fermented-diet system offset its extra labor requirements and made it more profitable than a Dry-diet system. The Hydrated-diet system was least profitable.

We note that feed collection was difficult to measure in the field and that evaporative water loss from Hydrated and Fermented feed treatments may have inflated feed consumption values. Feed was left outdoors in feed troughs for up to 13 days between feed delivery and leftover-feed collection and weighing. During this time, some feed dried and caked onto the feed troughs, but the values recorded by trial staff do not account for this evaporative water loss. Nonetheless, this type of wastage would probably also occur in a typical commercial flock – one reason why it is so important to carry out an experiment such as this in a setting representative of typical farm practices. It is of note that fermented feed performed well economically despite the likely over-estimation of raw consumption and feed-per-egg values.

Although overall performance suggests the nutritional status of the Fermented-diet birds was generally better than that of the Dry-diet birds in this study, they were slower to attain full production (Table 1). This could be explained by a period of adjustment when the experimental diets were introduced at 16 weeks. Engberg et al. (2009) reported that broilers introduced to fermented feed at 16 weeks initially appeared to find it less palatable or were less able to digest it. This effect may have constrained the productivity of Fermented-diet birds in our study relative to their full potential during the early part of the experiment, underestimating egg production in a Fermented-diet system where fermented feed is introduced earlier to the pullets.

Birds in the Hydrated feed treatment laid fewer, heavier eggs than birds on Dry or Fermented feeds in this study. Nutritional status of the hen is known to influence egg production, and sub-optimal nutrition can delay onset of lay (Bain et al. 2016; Bouvarel et al. 2011), leading to heavier eggs throughout the laying cycle (Rajendran 2011). Over the experimental period, birds on the Hydrated diet consumed less feed than other groups. In combination with their laying pattern, this suggests their nutritional status was less good than that of hens on Dry and Fermented diets. One possible explanation is swelling of the grains. The mash used for this experiment was whole-grain and contained wheat, barley and pea grains which swell up in water. While the Fermented feed was soaked for long enough to soften and break down the largest particles in the feed, the Hydrated feed may simply have become so bulky that the birds were unable to consume enough. It is probable that previous research demonstrating nutritional advantages associated with wet feed (Forbes 2003) used cracked or ground feeds with smaller particle size.

Research outcomes

Education and Outreach

Participation summary:

The Fermented Feed study was first introduced to members of the public during a Farm Walk event coordinated by the Washington State University Food Systems Team and Washington Tilth in 2018. The event was hosted at Foothills Farm on 9th July. There were 20 participants. Matt Steinman, the owner-manager of Foothills, showed the participants his feed fermentation equipment and demonstrated his feed delivery system: a tank of fermented slurry is transported on a trailer behind a gator to the field, where it is piped into troughs as the gator slowly drives down the field. With this system, feed delivery to a 500-bird flock takes just thirty minutes. However, the fermentation process represents extra labor and equipment relative to feeding dry mash, creating an incentive for Matt to find out whether it is worthwhile.

Louisa Brouwer provided a brief overview of the feeding trial, explaining the experimental goals, treatments and design.

The experimental flock of Golden Sexlink chicks arrived at the farm in October 2018. Data collection was carried out March - October 2019.

Matt Steinman presented on the trial at the 2019 Tilth Conference in Yakima. Around 20 people attended the session; 12 filled out evaluation forms. Evaluations were all positive and comments reflected a strong interest in on-farm research among the audience. A handout was created for the event and is attached here. Foothills farm project handout for Tilth 2019

Louisa Brouwer and Paul Weidner presented results of the trial at the San Juan Islands Agricultural Summit on Orcas Island in February 2020. Around 25 people attended the session and engaged in an energetic discussion of the fermented feed for poultry. Many participants were fermenting feed for small-scale flocks and were curious about the potential impacts on hen health. A factsheet summarizing the trial was distributed at this event and is attached here. Factsheet: Foothills Farm fermented feed study

A professional videography team, Serotonin Creative, created a video describing the trial. Filming took place at Foothills Farm during 2019 and 2020 so that the trial could be filmed in action and final results presented. The video is hosted online on the Youtube Channel of Scratch and Peck Feeds; Scratch and Peck also featured the video in an issue of their Flock's Journey member newsletter. At the time of writing (August 2020), the video has had 534 views.

An article about the Foothills Farm research written by Louisa and Matt was published in the September 2020 issue of Acres Magazine. Acres has 8,000 paid subscribers.

Matt and Louisa completed an interview with Mike Badger of the American Pastured Poultry Producers Association in June 2020. Mike intends to feature the interview on his podcast, Pastured Poultry Talk (1,000 subscribers), and the APPPA newsletter, Grit (distributed to 850 farms, estimated readership 1,300 people). He will also share the project video and the fact sheet through those channels.

With these outreach efforts, we estimate we may have reached some 10,000 people with what we hope is helpful and practical information about the potential of feed fermentation to improve pastured poultry economics.

Education and Outreach Outcomes

Pastured poultry

Benefits of fermented feed