Final report for GNC14-195

Project Information

Improved livestock distribution and grazing efficiency across the Northern Great Plains has led to structurally homogenous rangelands that greatly limit rangeland plant and animal biodiversity (Toombs et al. 2010, Becerra et al. 2013). Some range scientists have called for a shift to managing rangeland ecosystems for structural heterogeneity and biodiversity at larger scales, rather than managing for even grazing distribution (Fuhlendorf et al. 2012, Freese et al. 2014). However, typical management focuses on optimizing beef production (Ortega-S. et al. 2013, Sliwinski 2017), by promoting preferred forage species and increasing the efficiency of the grazing process (Vallentine 2001). Additionally, fire and burrowing mammals, such as prairie dogs, have been eliminated in an effort to maximize rangeland beef production (Freese et al. 2010, Augustine and Derner 2012, Fuhlendorf et al. 2012). These management decisions homogenize the landscape, thus decreasing habitat available to different wildlife species (Fuhlendorf and Engle 2001).

Because management decisions concerning rangelands are primarily made by private landowners, it is important to understand the attitudes that landowners, primarily ranchers, have about the processes that increase heterogeneity and about cross-boundary management to achieve conservation at larger scales. Thus, the first objective of this research was to examine ranchers’ attitudes about management across boundaries and strategies to create vegetation heterogeneity, and to determine the factors that influenced these attitudes. A second objective of this research was to determine what factors predicted behavioral intentions related to vegetation heterogeneity and cross-boundary management. We used qualitative and quantitative data to understand ranchers' attitudes about habitat heterogeneity and wildlife conservation.

In 2016 we completed the qualitative data analysis with data collected from 11 interviews, which resulted in seven themes: maintain control by reducing risk, wildlife are not our focus, the miracle of animal impact, managing to the middle, perceptions of the good rancher, trust insider, mistrust outsiders, and love of grasslands. We then developed a survey to collected quantitative data from landowners in Nebraska, South Dakota, and North Dakota. We received 595 usable surveys after distributing the survey to 2873 landowners. The analysis of these data indicated that attitudes about fire and prairie dogs were important predictors of a producer’s intent to use management that promotes vegetation heterogeneity or crosses property boundaries.

With the information gained from the interviews and survey, we developed an outreach publication that was mailed to the individuals who completed the mail survey. The publication included general results from the survey related to the topics that were most important to creating heterogeneity, including fire, prairie dogs, and threatened and endangered species.

The first objective of this study was to explore ranchers' perceptions of habitat heterogeneity and the processes that can create habitat heterogeneity in the Northern Great Plains. This objective was met through a qualitative interview process, to understand ranchers’ opinions of habitat heterogeneity across landscapes. We completed 11 interviews in Nebraska, South Dakota, and North Dakota.

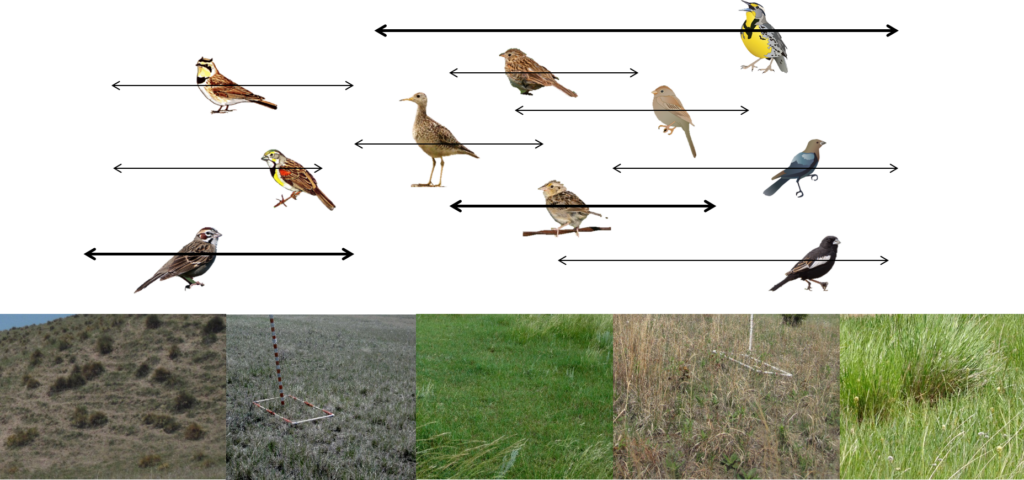

The second objective was to examine ranchers’ attitudes about vegetation heterogeneity, which is crucial for biodiversity in the Great Plains because different wildlife species require different types of habitat. For example, common nighthawks (Chordeiles minor) and mountain plovers (Charadrius montanus) nest on bare ground, whereas field sparrows (Spizella pusilla) and loggerhead shrikes (Lanius ludovicianus) require shrubby habitat (Figure 1). Additionally, we were interested in understanding ranchers’ attitudes about management across property boundaries, because ecosystem processes in the Great Plains, like fire, occur over large landscapes.

Figure 1. Birds in the Northern Great Plains require a variety of habitats, from bare ground to denser grass to shrubby. All of these habitats are required to ensure grassland biodiversity is achieved. (Photographs by M. Sliwinski)

The survey was mailed to ranchers in February 2016 after completing scale development and pilot testing. The variables that were assessed in the survey included attitudes about vegetation heterogeneity, landscape management, agreement with social norms, perceived control over ranch management, land use values, innovativeness, risk aversion, individualism, collectivism, and the intent to engage in behaviors that promote vegetation heterogeneity and landscape management. We also requested demographic information such as age, education, and amount of rangeland managed.

Cooperators

Research

To meet the first objective of this study, a qualitative, naturalistic approach was used, which involved in-depth interviews that resulted in rich and contextual qualitative data. This strategy was useful because it allowed participants to talk both broadly and deeply about topics related to vegetation heterogeneity, and allowed the researcher to explore and clarify topics that arose during the interview (Marshall and Rossman, 2010).

Interviews for this study were completed in the western semi-arid rangeland regions of Nebraska, South Dakota, and North Dakota. To identify ranchers for this study in Nebraska, key informants from the University of Nebraska Extension Service were asked for contact information of ranchers who might be willing to participate. In South Dakota, an NRCS agent and members from the South Dakota Grasslands Coalition provided contact information of ranchers. In North Dakota, mentors from the North Dakota Grazing Lands Coalition, who are ranchers, participated in interviews. Eleven interviews were completed with twelve individuals (one interview was with a husband-wife team): four in North Dakota, four in South Dakota, and three in Nebraska.

The survey was mailed to ranchers in February 2016 after completing scale development and pilot testing. We targeted the western portions of Nebraska, South Dakota, and North Dakota, because those are areas that still contain a large area of native grassland. We also targeted only landowners with >1000 acres of land, because we wanted to understand the attitudes of those individuals with control over larger areas of land, where managing for heterogeneity is more feasible. We received 595 usable surveys in February-April 2016. Data entry was completed by a lab assistant over the summer of 2016. Data analysis was completed in the fall of 2016, in consultation with the Nebraska Evaluation and Research Center. We used structural equation modeling to analyze the data, because there is inherent error when measuring attitudinal variables.

The qualitative data analysis resulted in seven themes: maintain control by reducing risk, wildlife are not our focus, the miracle of animal impact, managing to the middle, perceptions of the good rancher, trust insider, mistrust outsiders, and love of grasslands. The results highlighted that ranchers did not consider managing for heterogeneity reasonable, because optimizing harvest efficiency of available vegetation and livestock production were their primary objectives. There is no reason for producers to consider using tools that create vegetation heterogeneity when heterogeneity is not appreciated. However, many of the ranchers said they appreciated wildlife. The ranchers also suggested that “seeing is believing”, meaning that if ecologists and conservationists can show producers, rather than just tell them, that new management strategies are beneficial for both wildlife and livestock, they might be more willing to use those strategies. Ranchers often felt that ecologists and conservationists acted and spoke as though conservationists knew best and ranchers were not doing a good job. It is clear that there is not enough effort on the part of the conservationists to understand the intricacies and difficulties of raising livestock. Ranchers need to make a living; thus, beef production comes before wildlife management. The ranchers we spoke with suggested that monetary incentives can be strongly motivational, but that if the incentives don’t align with their pre-existing goals they are unlikely to be used. Alternatively, ranchers might manage for wildlife if ecologists can show that the new strategies are beneficial or neutral to livestock production.

The survey results indicated that attitudes about landscape management were generally positive, and that the participants understood that their management affected the larger landscape and future uses of the land. However, attitudes about fire and prairie dogs, two important ecosystem drivers in the Great Plains, were negative. Additionally, attitudes about fire and prairie dogs were important predictors of whether a participant was willing to engage in behaviors that promoted vegetation heterogeneity and landscape-scale management. Thus, fostering positive attitudes about fire and prairie dogs might be key to increasing vegetation heterogeneity and landscape-scale management in the Great Plains. We recommend that trusted advisors, such as University Extension staff, will have an important role to play in changing attitudes about fire and prairie dogs.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation summary:

We developed an extension-style report that summarized the results from the interviews and the survey, and also provided broad information about some of the strategies that can be used to create heterogeneity (e.g., prescribed fire, burrowing mammals). Our goal was to challenge a number of misconceptions that we identified, while also providing science-based information and links to resources that interested landowners could use to find more information. For example, one result in the survey was that most participants felt that fire provided similar management outcomes to livestock. Research has shown that fire can provide different benefits to wildlife than grazing alone, and together they can improve habitat even more. To counter the participants' conception of fire, we provided a number of reasons that fire can be beneficial, and also provided information on organizations that can help landowners conduct prescribed fires.

Project Outcomes

This research highlighted that ranchers often do not manage for wildlife, because livestock production was their primary objective. There is no reason for producers to consider using tools that create vegetation heterogeneity when the need for heterogeneity is not understood or appreciated. However, many ranchers indicated that they appreciated wildlife. Because there was very little prior research on the attitudes landowners have about habitat heterogeneity for wildlife, this research laid important groundwork for further studies that can drill down into the areas we identified as important barriers to the creation of heterogeneity. For example, we identified negative attitudes about fire and prairie dogs, two major contributors to habitat heterogeneity in the Northern Great Plains. We were also able to show that individuals with more positive attitudes about fire and prairie dogs were more likely to engage in behaviors that can create heterogeneity.

Because we identified some misconceptions about a number of topics related to habitat heterogeneity, we targeted an outreach publication to those areas with the goal of influencing attitudes and challenging the misconceptions. Although we did not measure attitudes after the publication was sent, our hope is that participants would have more positive attitudes about fire and prairie dogs, and have access to further information if they wanted to learn more about those topics.

This project highlighted the dichotomy between agricultural producers and academics. Producers are working hard on the land to ensure they can make a living to support their families, and they often felt that "outsiders" had very little appreciation for the difficulties they face. They also felt that academics have a "PhD attitude" that prevents useful dialogue from taking place. It is imperative for researchers to develop positive relationships with producers to be able to engage them in research and learn from them about their needs and the difficulty they may have in implementing new management strategies that are being studied.

One recommendation we have is for a future study to examine attitude changes after information is provided in an outreach report. It is also important for outreach reports to be based on the results of the research that was conducted with landowners, rather than simply an informational piece. Because ranchers can feel alienated and do not like the "PhD attitude", we were very deliberate in the language we used on the outreach report, the results we included, and in providing sources where the participants would be able to find more information. However, we were unable to examine how well participants received this publication, which would have been very useful. Including a postage-paid comment card or very brief survey along with the mailing could be useful and relatively easy for the participant to complete.