Final report for GW22-235

Project Information

An essential aspect of making agriculture economically, environmentally, and socially sustainable is to look at food production holistically. From a crop being planted to being brought home to eat, assessing how to increase the sustainability of all steps is fundamental. In vegetable systems, the challenges of intense labor shortages across the USA, increased consumer demand for diverse and locally sourced produce, and a changing climate underscores the need for versatile integrated management tactics. Yet, little research has been done to jointly assess weed management, climate change, and value-added market opportunities on organic vegetable farms. To address this knowledge gap, this research and education project combined on-farm research with experimental plots and growth chamber studies to 1) define the critical period of weed control (CPWC), 2) assess the impact of elevated CO2 on weed-crop competition, and 3) investigate value-added market opportunities in organic vegetable production. Due to their high market value and management challenges, this project used carrots (Daucus carota var. sativus) as a model crop. Additionally, we used radish (Raphanus sativus var. French breakfast) due to its successful emergence in growth chambers and the impact of weed/crop competition on its biomass. By assessing yield, quality, and labor needs, results from this research will improve growers’ quality of life by enabling them to optimize inputs, crop quality, value-added products, and net returns. To secure the adoption of our results, education outcomes included field days, a short video, Extension articles, and community outreach. In addition, plots and research results have been used as educational tools to explain ecologically-based crop management in various classes at Montana State University.

Research Objectives

- Objective 1. Determine the length of the critical period of weed control (CPWC) in organically grown carrots (Kubinski, Brown, Gustafson, Chance, Burgess, Menalled)

- Objective 2. Evaluate the impact of elevated CO2 on radish growth and weed competition (Kubinski, Menalled)

- Objective 3. Investigate value-added products for vegetables in the Great Plains, specifically those impacted by weed competition (Kubinski, Walsten, Williamson, Burr, Ebel, Menalled)

- Objective 4. Estimate enterprise budgets for carrot production that include the different weed management scenarios (Kubinski, Ebel, Menalled)

Educational Objectives

- Objective 1. Develop and deliver an off-campus education program aimed at enhancing the sustainability of vegetable farms (Kubinski, Brown, Gustafson, Chance, Ebel, Walsten, Williamson, Burr, Burgess, Menalled)

- Objective 2. Enhance student active learning on the sustainable management of vegetable farms (Kubinski, Ebel, Burgess, Menalled)

Cooperators

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

Research

Objective 1. Determine the length of the critical period of weed control (CPWC) in organically grown carrots

We expanded our 2021 pilot study by conducting complementary studies during the 2022 and 2023 growing seasons at Townes Harvest Garden, Bozeman, MT, the MSU research and education farm (https://townesharvest.montana.edu/), and cooperators’ farms. Specifically, we assessed the length of the CPWC, the period in which weed removal is necessary to avoid yield loss, in organically managed vegetable crops. At Townes Harvest Garden, the experiment followed a Randomized Block Design with four replications and four rows of carrots each. Seedbed preparation followed the farm manager's practices and included multiple tillage passes to achieve a fine seedbed to ensure carrot seed germination and manage weeds before crop planting. Before seeding, soil compaction was measured using a soil penetrometer at four locations per plot and at four depth ranges (0–15, 15–30, 30–45, and 45–60 cm). Soil nutrient content was evaluated with two randomly located soil core samples per rep. The soil was separated by depths (0-6 and 6-24 cm) for each sample and analyzed for Olsen P, potassium, calcium, organic matter, and pH.

Experimental plots (2.5m x 4 rows) consisted of eight randomly applied weeding treatments, selected based on the 2021 pilot study: 1) weedy up to the 2-leaf stage, 2) weedy up to the 6-leaf stage, 3) weedy up to the 10-leaf stage, 4) weed free up to the 2-leaf stage, 5) weed free up to the 6-leaf stage, 6) weed free up to the 10-leaf stage, 7) season-long weedy, and 8) season-long weed free. To encompass a wide range of environmental conditions, six trials were carried out with different planting dates (June 3rd and June 23rd in 2021, June 28th and July 14th in 2022, and May 30th and June 17th in 2023). Below and aboveground carrot biomass, marketability, and Brix sugar content were measured at harvest.

To fully understand the impact of the proposed weed management tactics, it was necessary to expand the research beyond yields and evaluate weed communities1. This information is crucial for assessing the potential input of unwanted weed seeds into the seed bank, particularly from perennial rhizomatous weeds like Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense) and field bindweed (Convolvulus arvensis), both of which pose considerable threats to carrot production2,3. To assess weed communities, all weed species and their abundance were recorded along a 10-meter by 0.2-meter (length, width) transect of rows of carrots at Towne Harvest Garden.

To evaluate the applicability of our results, a reduced version of this study was conducted by our farmer collaborators at Amaltheia (2022), Chace Farm (2022), and Bodhi (2022 and 2023). At each farm, treatments included weedy up to the 4-leaf stage, weed-free up to the 4-leaf stage, season-long weedy, season-long weed-free, and weed management based on farmer’s practices. A farmer’s practice treatment allowed us to compare the production and market benefits or shortcomings of using the CPWC to make management decisions. Like the experimental plots at Towne Harvest Garden, carrot belowground biomass, aboveground biomass, marketability, and Brix sugar content were collected at harvest from the on-farm plots.

Data analysis.

Critical Period of Weed Control. To generalize our results, the carrot leaf stage was correlated with growing degree days (GDD) accumulated from crop emergence to reduce seasonal variability and better align with crop stage4. We used a four-parameter log-logistic regression analysis to assess the length of the CPWC4:

Y = [C + (D - C)] / {1 + exp[B(log X – log E)]} (Equation 1)

Where Y = relative response of the studied variable (percentage yield, Brix sugar, or marketability of the season-long weed-free response), C = lower limit, D = upper limit, X = time expressed in GDD, E = GDD giving a 50% response between the upper and lower limits, B = slope of the line at the inflection point. Then, using the curve the model created, an estimated effective dose of 5% acceptable yield loss was applied to identify the start and end of the CPWC in GDD. All analyses were conducted utilizing the drc Package of the R statistical environment (http://cran.at.r-project.org). We use the plotrix, sciplot, and ggplot packages of R to graphically represent the impact of the length of crop-weed competition on yield, biomass, sugar content, and marketability. Simple linear regressions were conducted to evaluate the relationship between carrot measurements.

Weed community composition. We assessed weed species richness and diversity using the R statistical environment (Vegan) with appropriate linear mixed-effects models. Weed composition community composition was evaluated with a permutational multivariate ANOVA (perMANOVA) in combination with unconstrained multivariate ordination analyses such as nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS).

Objective 2. Evaluate the impact of elevated CO2 on radish growth and weed competition

Our initial Objective 2, "Evaluate the impact of on-farm generated biofertilizer as a soil amendment on carrot growth and weed competition," was modified due to various issues. The inability to track and account for the variability of input into the biodigesters created potential inconsistencies in the biofertilizer amendment. Therefore, pinpointing which aspects of the biofertilizer specifically influenced weed-crop competition would have been challenging. Furthermore, some of the stored biofertilizers froze over the winter, and their biotic components may have been altered, potentially contributing to further inconsistencies in the amendment. In addition to difficulties with the biofertilizer, we could not achieve a successful, consistent crop emergence in a greenhouse setting due to carrot seeds' small size and sensitivity.

Given these challenges, we modified Objective 2. to "Evaluate the impact of elevated CO2 on radish growth and weed competition." This objective follows the core topic of evaluating changes in weed-crop competition with the addition of fertilizer by applying CO2 as a gas fertilizer amendment. Modifying this objective allowed us to expand the evaluation of the length of the CPWC (Objective 1) by incorporating the impacts of climate change into the scope of the research project. Specifically, we evaluated how the CPWC will change with predicted CO2 levels. In the face of climate change, weed management should be adaptive, and studying how the competitive ability of weeds and crops will shift provides critical information to producers to develop preventive steps in their management practices5.

Using growth chambers (model CMP6050, Conviron 6050), we compared weed-crop competition in the ambient and predicted elevated CO2 levels. Rather than carrots, we used radishes due to their ability to grow quickly and consistently under growth chamber conditions. For our weed, we used Bromus tectorum (downy brome, cheatgrass) and Fagopyrum esculentum (common buckwheat) due to their ability to grow in a growth chamber and their prevalence in the region. Like the field study on the CPWC (Objective 1), we established six treatments of weedy up to or after different growth stages and a season-long weedy and weed-free treatment for each weed species. Five replications of each treatment were carried out in ambient (419ppm) and elevated (720ppm) CO2 conditions, and the whole study was repeated twice for each weed species. Our proposed modified objective gives us more precise and dependable results while maintaining the initial goal of studying weed-crop competition by adding fertilizer.

Data analysis.

Plant emergence. For each species, we estimated the mean time of emergence (MTE) as:

MTE = ∑nidi / ∑nI (Equation 2)

Where ni is the number of seedlings at time I, and di is the number of days from the beginning of the experiment to time i.

Percentage emergence inhibition (EI%) was also calculated as follows:

EI% = [(Eambient – Eelevated)/ Eelevated] * 100 (Equation 3)

Eambient and Eelevated are the number of seedlings that emerged with ambient and elevated CO2, respectively.

Critical Period of Weed Control. The analysis of the CPWC followed the methods described in Objective 1. Radish growth stages were based on GDD accumulated from crop emergence. As in Objective 1, a four-parameter log-logistic regression analysis was used to assess the length of the CPWC4 as:

Y = [C + (D - C)] / {1 + exp[B(log X – log E)]} (Equation 1)

Where Y = relative response of the studied variable (percentage yield, Brix sugar, or marketability of the season-long weed-free response), C = lower limit, D = upper limit, X = time expressed in GDD, E = GDD giving a 50% response between the upper and lower limits, B = slope of the line at the inflection point. Then, using the fitted model, an estimated effective dose of 5% acceptable yield loss was applied to the curve created by the model to identify the start and end of the CPWC in GDD. All analyses were conducted utilizing the drc Package of the R statistical environment (http://cran.at.r-project.org). The plotrix, sciplot, and ggplot packages of R were used to graphically represent the impact of the length of crop-weed competition on yield.

Objective 3: Investigate value-added products for vegetables in the Great Plains, specifically those impacted by weed competition

Assessing possible value-added products of rejected vegetables can contribute to farms' economic and environmental sustainability by increasing profitability and reducing waste. This is especially relevant to crops such as carrots that may not be market-ready due to aesthetic concerns. Our preliminary study found that carrots with higher weed competition scored a lower qualitative marketability rating given their smaller size and often misshapen appearance (Figure 1). Despite these unmarketable carrots being inadequate for the market, they can be incorporated into value-added products such as juices, jams, and pickles instead of tossed away. To investigate this possibility, we evaluated the potential market values of otherwise unmarketable products in collaboration with two locally owned food processing companies: Farmented Foods and Root Kitchen and Cannery.

Figure 1. Example of unmarketable carrots and potential candidates for value-added products

Farmented Foods (https://www.farmented.com/) is committed to reducing food waste through the fermentation of local, unmarketable vegetables and is evaluating the potential processing of weed-impacted carrots and estimating their marketability within value-added products. Roots Kitchen and Cannery (https://www.rootskitchencannery.com/) was founded in 2012 to craft canned goods using locally sourced fruit and produce. The products evaluated for incorporating unmarketable carrots were curried carrot pickles by Roots Kitchen and Cannery and spicy carrot chips by Farmented Food. Both companies provided an estimate of the labor cost and the potential price they would pay the farmer for the raw vegetables. This information was incorporated into the enterprise budgets (Objective 4). In addition, they identified potential shortcomings in adopting the produce into their products.

Objective 4. Estimate enterprise budgets for carrot production that include the different weed management scenarios

Enterprise budgets help producers make informed decisions when allocating limited resources such as land, labor, and equipment. We adapted the protocols developed by Iowa State University 6 and farmer input to create enterprise budgets that evaluated the financial impact of proposed weed management tactics and potential income from value-added products (Objective 3). We collected the following data: fixed and variable production costs, including land and irrigation, labor, capital, machinery and equipment, and capital, using information provided by local vegetable producers, the Montana Department of Agriculture, and Kwantlen Polytechnic University budget estimates. The returns were based on standard prices and yields received by local farmers. Labor was valued using survey results of local producers collected by Sophia Lattes, a graduate student at Montana State University. Yields were obtained from our field trials (Objective 1). All estimates were developed on an acre basis for ease of conversion to smaller areas if needed. The enterprise budget did not include marketing and transaction costs as they vary based on whether products are distributed through a community-supported agriculture share, wholesaler, or farmers’ market outlet. While the estimated budgets may not reflect individual farms' specific environment and labor, they can be used to train farmers on approaches to maximize net returns based on market goals, weed pressure, and production costs (see Education plan below).

References – Research Methods and Analyses

- Neve, P., J. Barney, Y. Buckley, et al. 2018. Reviewing research priorities in weed ecology, evolution, and management: a horizon scan. Weed Research 58: 250-258.

- OAEC, 2013a. A survey report on the research and educational needs of organic grain producers in Montana. http://www.oaecmt.org/reports.html.

- OAEC, 2013b. A survey report of the research and educational needs of Montana's organic vegetable and herb producers. http://www.oaecmt.org/reports.html

- Knezevic, S. and A. Datta. 2015. The critical period of weed control: revisiting the data. Weed Science Special Issue: 188-202.

- Prato, T. 2008. Conceptual framework for assessment and management of ecosystem impacts of climate change. Ecological Complexity. 5(4): 329–338.

- Menalled, F., D. Buhler, and M. Liebman. 2005. Composted swine manure affects germination and early growth of crop and weed species under greenhouse conditions. Weed Technology 19: 784-789.

Objective 1. Determine the length of the critical period of weed control in organically grown carrots

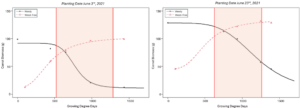

As expected, weed competition reduced carrot yields, with carrot biomass decreasing on average by 31.2% ± 10.5 (mean±SE) in plots subjected to season-long weed competition compared to weed-free plots. All weedy and weed-free treatments up to the pre-determined growth stages also caused some level of yield loss compared to the season-long weed-free treatment. Based on the fitted model and with a 5% acceptable yield loss, the CPWC was determined for early and late-planted carrots in each growing season (Figure 2). Notably, variability was observed between the different trials in both the timing of the CPWC and its duration. While GDD was used to reduce variability across growing seasons, planting dates, and weather patterns by relying on temperature accumulation, differences in the CPWC may still arise due to environmental conditions, variations in weed communities, or pre-sowing weed management1.

Figure 2. Predicted CPWC for organic carrots in 2021, 2022, and 2023 at varying planting dates based on an acceptable yield loss of 5%.

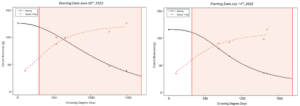

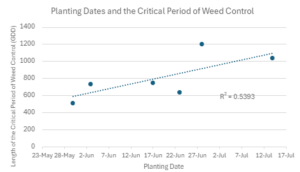

To help explain the observed variability, we evaluated the relationship between the length of CPWC and planting date, especially since planting timing has been found to influence the CPWC in conventional carrot production2. In agreement, we observed an increase in the length of the CPWC with later planting dates (linear regression, R2= 0.5, p-value= 0.09) (Figure 3). This suggests that the later carrots are planted, the longer the period during which weed management is necessary.

Figure 3. Linear regression of planting dates and length of the critical period of weed control (R2= 0.54, p-value= 0.09)

The observed trend between planting date and the CPWC may be attributed to the emergence patterns of dominant weed species. Our analysis of weed communities identified redroot pigweed (Amaranthus retroflexus) as the region's most prevalent weed on vegetable farms, especially within carrots. Redroot pigweed typically begins emerging from late spring to early summer and continues to emerge throughout the growing season3. With later planting dates, this dominant, highly competitive weed will likely have a greater emergence and density and, therefore, may explain the increased time needed for weed management during the growing season. Furthermore, due to its late-season emergence relative to other common weed species, redroot pigweed may avoid being controlled by early-season weed management practices, such as preparing a false or stale seedbed. Other dominant species observed in carrot crops included Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense), common sowthistle (Sonchus oleracus), and quackgrass (Elymus repens). Another possible explanation for the extended CPWC in later plantings is reduced labor availability for weed management before sowing carrots. Managing weeds in carrot beds before planting is crucial to minimizing weed pressure during the growing season, with farmers suggesting cultivation as frequently as every ten days until sowing (Mac Burgess, personal communication, 4 June 2024). As more crops are cultivated later in the season, fewer resources may be available for weed management before planting, potentially extending the CPWC with those carrots that are sown later in the season.

In addition to evaluating how the CPWC can be used to enhance yields with less weeding requirements, we also determined that it can be used to optimize the marketability of carrots. Across all trials, the average CPWC to maintain carrot quality/marketability with a 5% acceptable loss in marketability score ranged from 648.9 ± 82.7 GDD (mean±SE) and 1971.0 ± 214.6 GDD (mean±SE). Compared to the CPWC for optimizing yield, the CPWC for marketability occurs slightly later in the season, requiring more GDD accumulation. Nevertheless, there is substantial overlap between the two, suggesting that the CPWC can achieve both desired yields and marketability. Notably, carrot biomass and quality rating were positively correlated (R2 = 0.32, p-value < 0.001), indicating that larger carrots tended to have higher quality. This correlation may contribute to the observed overlap in the CPWC for marketability and yield.

The on-farm plots provided valuable firsthand experiences demonstrating how the timing of the CPWC can vary year-to-year and farm-to-farm, especially given the variability in weed densities and management practices. Across all on-farm plots, weed-free carrots consistently had the highest biomass compared to all other treatments, including farmer-managed plots, while the weedy season-long had the lowest. At Amaltheia, farmer-managed carrots exhibited greater biomass than weedy and weed-free up to the 4th leaf stage, likely due to the relatively low weed pressure observed on the farm. In contrast, at Chance Farm, farmer-managed carrots had lower biomass than both weed-free and weedy carrots at the 4th leaf stage weed and weedy carrots. This can be attributed to the abandonment of cultivation in the carrot bed for the season due to high weed pressure. At Bodhi Farms, in both years, the farmer-managed carrots were smaller than weed-free up to the 4th leaf stage and smaller than the weedy up to the 4th leaf stage. This may be due to high weed pressure or the high-density planting of carrots on the farm.

Objective 2. Evaluate the impact of elevated CO2 on radish growth and weed competition

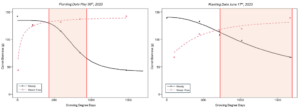

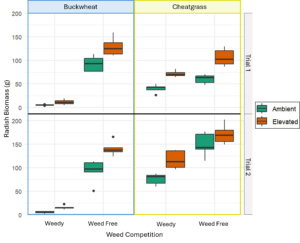

Distinct differences were observed between elevated and ambient conditions in the growth and competitive effect of radish, buckwheat, and cheatgrass. In all three species, greater biomass was observed in plants grown in elevated CO2 conditions. Notably, radish yields were higher in both weedy and weed-free season-long conditions for both weedy species when grown in elevated CO2 (Figure 4). We also evaluated the impact of CO2 on plant emergence (Table 1). MET was not impacted by changing CO2 conditions for radishes and only marginally shifted for weedy species. EI% between the ambient and elevated CO2 conditions had greater differences across species. Radish emergence was inhibited by elevated CO2, while the opposite was observed in the weedy species. Therefore, although the timing of emergence was similar, the number of seedlings emerging varied considerably between ambient and elevated CO2, favoring weedy species.

Figure 4. Comparison of radish biomass with no weed competition throughout the experiment (weed-free season-long treatment) and weed competition for the entirety of the experiment (weedy season-long treatment) for cheatgrass or buckwheat under ambient and elevated conditions.

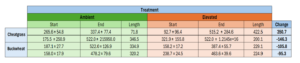

Table 1. Average Mean Emergence Time (days) and Percentage Emergence Inhibition (%) of radish, cheatgrass, and buckwheat in ambient and elevated CO2 conditions.

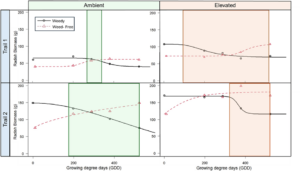

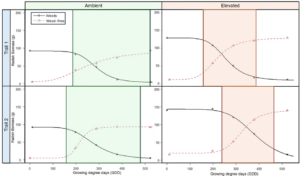

Results assessing the impact of CO2 on the CPWC varied by weed species (Table 2). In competition with cheatgrass, the radish CPWC had inconsistent results, with an increase in Trial 1 by 350.7 GDD and a decrease in Trial 2 by 146.3 GDD (Figure 5). Even though cheatgrass seeds were sourced from the same population, differences between trials may be explained by the high plasticity and genetic variability within cheatgrass populations4. In contrast, the radish CPWC in competition with buckwheat had more consistent results. Unlike cheatgrass, buckwheat is a volunteer weed commonly used as a cover crop. As such, buckwheat populations are less likely to have extensive genetic variability and plasticity compared to an invasive grass like cheatgrass. Our results show that in competition with buckwheat, the radish CPWC decreased in elevated CO2 conditions by 105.8 GDD in Trial 1 and 95.3 GDD in Trial 2 (Figure 6). Specifically, the CPWC ended earlier in both trials under elevated CO2 conditions, indicating that weeding could be stopped earlier in the season without resulting in significant yield loss. The increased competitive ability of radish in elevated CO2 may be due to its enhanced aboveground competitive ability. In the buckwheat CPWC trials, radish aboveground biomass increased by 47.1% ± 4.8 (mean ±SE), while buckwheat aboveground biomass only increased by 35.7 % ± 4.4 (mean ± SE). This may explain the shift to an earlier end of the CPWC if the larger amount of aboveground biomass enabled the radish to outcompete the buckwheat.

Table 2. Differences in the range and length of the radish critical period of weed control between species under ambient and elevated CO2 conditions.

Figure 5. The critical period of weed control of radish under cheatgrass competition in elevated and ambient conditions

Figure 6. The critical period of weed control of radish under buckwheat competition in elevated and ambient conditions

Objective 3: Investigate value-added products for vegetables in the Great Plains, specifically those impacted by weed competition

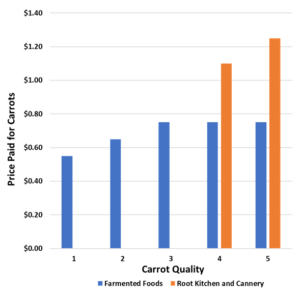

When collecting data for CPWC, the sugar content of different carrot qualities (1-5) was measured to evaluate the impact of competition on taste. We found weak evidence (linear regression, R2 = 0.017, p-value= 0.0013) for a correlation between sugar content and marketability. This suggests that the marketability/looks of a carrot does not impact its taste. Due to this, unmarketable carrots provide an excellent opportunity to explore developing value-added products with unmarketable produce. We worked with two local food processors on the carrot value-added product they produce: Farmented Foods and their “Spicy Carrots” and Roots Kitchen & Cannery and their “Curried Carrot Pickles” (Figure 7). Farmented Foods “Spicy Carrots” consists of sliced carrots chips pickled with spices. Roots Kitchen & Cannery’s “Curried Carrot Pickles” use carrot sticks pickled with spices. Despite the similarities in products, there were distinct differences in the companies’ ability to use unmarketable carrots.

Figure 7. Value-added products created with unmarketable carrots: Farmented Foods “Spicy Carrots,” and Roots Kitchen & Cannery, “Curried Carrot Pickle.”

According to our survey, Roots Kitchen & Canney was unwilling to use lower-quality carrots. The company expressed interest in only purchasing carrots of the high and highest quality (categories 4 & 5) as they were unable to use unmarketable carrots due to inconsistencies in their length and thickness that would make them difficult to process. Even from a marketability score of 5 to 4, Roots Kitchen and Cannery estimated labor demands would be increased by 20 lbs. an hour. For the highest quality, they were willing to pay $1 and for high-quality carrots, $1.10 (4), a 12% reduction in price paid (Figure 8).

Alternatively, Farmented Foods was willing to purchase the carrots at any quality stage. At the highest quality (5), high quality (4), and medium quality (3) categories, Farmented Foods was willing to purchase the carrots for $0.75/lb. For low carrot quality (2), Farmented Foods was willing to pay $0.65/lb, a 13% reduction in price, and for the lowest quality (1), $0.55/lb, a 27% reduction in price (Figure 8). The main limitation identified by Farmented Foods for using unmarketable carrots was additional labor time. Specifically, many of the low and lowest quality carrots had forking and would require more time to clean and ensure all dirt was removed. As a result of the increased labor demand, Farmented Foods would not pay as much for these higher-quality carrots but still would be willing to use them.

Figure 8. Price food processors are willing to pay for 1lb of each carrot quality category (1-5).

The difference in unmarketable carrot quality usability in value-added products between Farmented Foods and Roots Kitchen & Cannery was largely due to product type. Because Farmented Food’s product uses sliced carrots, they are less limited by uniformity among them. Alternatively, Roots Kitchen & Cannery’s product uses carrot sticks, which require more consistency with their carrots in length and thickness. Therefore, food processors are more likely to purchase unmarketable produce if the product being created does not require distinct shapes of the carrots, for example, juices or pulps. Surveys also found for both companies that the additional labor required for processing lower-quality carrots was a significant barrier to their adoption. Rather than the look itself, a more substantial concern of food processors is the added labor time cleaning or processing them would take. These results suggest that to create more market opportunities for value-added products using “ugly” produce for farmers, products must not require uniform carrot sizes and ideally have low labor requirements for processing.

Despite these limitations, results show that “ugly” vegetables impacted by weed competition still have the potential to be used in value-added products. Growers can sell this otherwise unmarketable produce to food processors of value-added products or make them their own, resulting in additional revenue from vegetables that would otherwise be composted (See Objective 4).

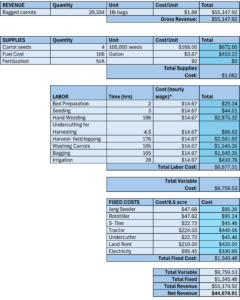

Objective 4. Estimate enterprise budgets for carrot production that include the different weed management scenarios

The budget was developed using diverse resources to attain the most realistic estimations, including data collected directly from this project and others at Montana State University, as well as direct consultation with farmers Dr. Mac Burgess, Sophie Lattes, and Nate Brown. Additionally, on-farm data was collected on farm operations at Towne Harvest Garden by Dr. Mac Burgess, Sophia Lattes, and students enrolled in the Towne's Harvest Practicum (SFBS 296, Burgess) course. Lastly, budgets developed by extension and universities were referenced.

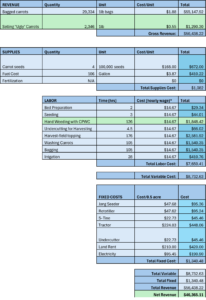

Based on these sources, we estimated that the profitability from an acre of carrots is $44,074.91, considering all fixed and variable costs aside from marketing (Table 3). In a weed-free scenario, we estimated higher profitability and increased carrot size and marketability, bringing the total revenue to $51,360.39. However, achieving and maintaining weed-free conditions is an enormous and, most often, unrealistic feat. Therefore, using the CPWC and the sale of “ugly” produce to companies creating value-added products provides a more practical approach for farmers to increase profitability. Using the CPWC, labor requirements can be reduced by over 1/3 when weeding weekly to maintain weed-free conditions. As a result, we determined that the CPWC can save farmers $1,026.58 in labor costs annually. Additionally, it is estimated that in farmer-managed carrots, ~8% are deemed “unmarketable” due to their appearance and size based on yield results. Incorporating the results from Objective 3, even if all these carrots were in the lowest quality rating of category 1, they still have the potential to be sold for a minimum of $0.55/lb. Therefore, farmers can potentially increase their gross revenue by $1,290.00. Combined, both weed management based on the CPWC and the sale of unmarketable produce have the potential to result in a net income of $46,365.11 (Table 4).

Table 3. Enterprise budgets for 1 acre of organic carrots.

Table 4. Enterprise budget for 1 acre of organic carrots with the incorporation of the critical period of weed control and sale of unmarketable produce for value-added products.

References – Research Results

- Ramesh K, Vijaya Kumar S, Upadhyay PK, Chauhan BS. 2021. Revisiting the concept of the critical period of weed control. J Agric Sci. 159(9–10):636–642.

- Swanton CJ, O’Sullivan J, Robinson DE. 2010. The Critical Weed-Free Period in Carrot. Weed sci. 58(3):229–233.

- Mohler CL, Teasdale JR, DiTommaso A. 2021. Manage weeds on your farm: a guide to ecological strategies. College Park: Sustainable Agriculture Research & Education (SARE).

- Hufft RA, Zelikova TJ. 2016. Ecological Genetics, Local Adaptation, and Phenotypic Plasticity in Bromus tectorum in the Context of a Changing Climate. In: Germino MJ, Chambers JC, Brown CS, editors. Exotic Brome-Grasses in Arid and Semiarid Ecosystems of the Western US [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing; [accessed 2023 Aug 4]; p. 133–154.

Research Outcomes

Objective 1. Determine the length of the critical period of weed control in organically grown carrots

Before recommending what CPWC to use for organically grown carrots, variability between trails and farms should be considered when making recommendations. Specifically, we observed increased CPWC duration with later planting dates. The composition of the weed communities present may explain this. In areas with later-emerging weeds, competition may intensify later in the season, requiring additional weeding to minimize competition with the crop. Based on these results, to minimize weeding requirements, early planting should be prioritized to give carrots a head start against dominant, late-emerging weeds. If early planting is not feasible, growers can decrease weeding requirements through early-season weed management before carrot planting. Pre-sowing weed management could be done by frequent cultivation, ideally every ten days (Mac Burgess, personal communication, 4 June 2024). Additionally, cover crops can offer biological control for weeds by providing early season weed suppression1.

Averaging across all six trials carried out to account for variability, we determined that the CPWC in organically grown carrots generally extends from 490.9 GDD to 1331.3. GDD. Therefore, we recommend that growers aim to maintain their carrots weed-free during this time to maintain high yields and minimize resources required for weed management, but also consider how this period may shift depending on when their carrots are planted. Since not all farmers track GDD on their farms, this window can also be translated into growth stages. Specifically, we suggest maintaining weed-free conditions from the 4th to the 10th leaf stage of carrots.

In addition to optimizing yields, applying the CPWC can help growers maximize labor cost savings2. This is particularly relevant given the rising costs of farm labor, which account for approximately 10% of on-farm expenses, with higher labor demands on organic farms due to the need for hand cultivation for weeding3. By applying the CPWC, growers can reduce labor demands and lower costs (see Objective 3). However, while removing weeds after the CPWC may not enhance yields, late-season weed management may be necessary to prevent weed contributions to the soil seed bank. This is particularly relevant for growers with low weed pressure on their farms.

The CPWC can inform management decisions beyond weed control. Rather than solely focusing on weed competition, Sophia Lattes, a graduate student at Montana State University, is exploring how the CPWC determined in this study can guide the timing of interseeding cover crops in carrots. Since the CPWC identifies when carrots are no longer vulnerable to yield reductions from weed competition, this information could serve as a valuable guideline for determining the optimal time to plant cover crops that ensures that cover crops do not compete with the crop.

While we evaluated the weed communities on the farm and have indications that the dominant weed species may influence the variability in the CPWC, future research should focus on directly assessing the differences in weed communities. Ideally, a complete randomized block design for determining the CPWC would be established on multiple farms, with weed community data collected in each plot to identify differences in competition at a finer scale and facilitate direct comparisons across farms. Furthermore, pre-sowing weed management's impact on the CPWC length should be evaluated. This could be achieved by applying the same study design in carrot beds with varying levels of pre-seeding weed management, such as comparing flame weeding for a stale seedbed preparation or varying the number of cultivations performed before planting for a false seedbed preparation.

Our study demonstrated that applying the CPWC can also enhance crop marketability. In vegetable production, crop appearance and marketability directly impact farmers’ revenue4. We observed that increased weed competition led to lower marketability scores. However, there was a substantial overlap between the CPWC identified for carrot yields and marketability, indicating that managing weeds within the CPWC can both optimize yield and marketability, all while reducing labor demands.

Objective 2. Evaluate the impact of elevated CO2 on radish growth and weed competition

The study expands the body of evidence that climate change will impact weed crop competition and its associated management recommendations. Currently, most research on weed-crop competition has focused on the interactions between species without specifically addressing how these dynamics will directly influence weed management recommendations. We assessed how farmers may have to alter both the amount and timing of labor required to avoid yield reduction in their crops under predicted CO2 conditions.

We determined that the impact of CO2 on the length of the CPWC is species-dependent. Overall, our results suggest that elevated CO2 conditions may have variable impacts on the CPWC depending on the specific weed species and populations. Since many weed species have high plasticity, compounded with environmental variability in the changing climate, future studies should attempt to identify which factors may directly influence the CPWC through multivariate analyses and field studies.

While we observed variable results in our evaluation of the CPWC of radish competing with cheatgrass, we saw a consistent decrease in the length of the CPCW and an earlier end to required weeding in competition with buckwheat. These findings suggest that in elevated CO2 conditions, less weeding would be needed and that the radish may be more competitive. The lack of variability in results compared to the cheatgrass trails may be explained by buckwheat being a cover crop with reduced genetic variability and plasticity. Our findings also suggested that buckwheat is less competitive under elevated CO2 conditions. Given its rapid growth, buckwheat is often selected as a cover crop for weed suppression. However, if buckwheat becomes less competitive in elevated CO2, its weed-suppressive abilities could be reduced with climate change. This highlights the importance of knowing what weeds are present on farms to be able to predict how management will change under futureCO2 conditions.

Objective 3. Investigate value-added products for vegetables in the Great Plains, specifically those impacted by weed competition

Results from this study indicate that weed-impacted vegetables can be incorporated into value-added products. Specifically, carrots are an excellent candidate given their sugar content or taste is unimpacted by their marketability score based solely on their looks. Incorporating “ugly” produce enables farmers to profit from produce that would otherwise be discarded or used for composting. Therefore, we suggest that the crop should not be abandoned if a farmer misses the opportunity to manage weeds during the CPWC or has other issues that could impact carrot looks. Given that 20-40% of produce is discarded before it gets to consumers, often due to cosmetic imperfections, using the “unmarketable” produce will also increase food availability4. There is an even greater opportunity to address food accessibility through value-added products if they are pickled and preserved. Future research should compare consumer willingness to adopt value-added products made with “ugly” produce versus purchasing them directly.

Objective 4. Estimate enterprise budgets for carrot production that include the different weed management scenarios

Combining the CPWC with information regarding alternative markets for rejected products indicated an increase in farm's net revenue by over 5%. Our enterprise budget provides needed information on estimating costs and revenue associated with small-scale organic carrot production in the NGP. Because the budget is detailed, farmers can adjust the numbers to fit their farms better if needed. These will guide additional enterprise budgets for crops and small, diversified organic vegetable farms.

References – Research Outcomes

- Błażewicz-Woźniak M, Wach D, Patkowska E, Konopiński M. 2019. The effect of cover crops on carrot yield (Daucus carota L.) in ploughless and conventional tillage. Hortic Sci. 46(2):57–64.

- Brown B, Gallandt ER. 2019. To each their own: case studies of four successful, small-scale organic vegetable farmers with distinct weed management strategies. Renew Agric Food Syst. 34(5):373–379.

- Census of Agriculture Farm Production Expenses: 2022 and 2017. 2022.

- Yuan JJ, Yi S, Williams HA, Park O-H. 2019. US consumers’ perceptions of imperfect “ugly” produce. BFJ. 121(11):2666–2682.

Education and Outreach

Participation Summary:

Our targeted audience included vegetable growers, Extension agents, agricultural educators, undergraduate students, and local community members interested in sustainable agriculture and food systems. Emma Kubinski, the graduate student working on this project, has led various educational and outreach activities. To do this, she worked in close collaboration with Drs. Menalled, Ebel, and Burgess who have a strong record of working closely with commodity groups and local producers to disseminate the results of their applied research to growers across the region and teach undergraduate and graduate courses.

To reach a large audience, Emma Kubinski engaged collaborators and used stakeholder participation to disseminate results from this study to organic and conventional producers and other interested groups. She has worked closely with the Montana Organic Association and farmer collaborators to promote an open invitation to producers and stakeholders who wish to view active field experiments involving weed management tactics and value-added markets. Furthermore, during Montana State University’s Field Days, attendees visited plots, discussed research objectives and results, and provided inputs and suggestions. Emma Kubinski coordinated with the project collaborators so that they had the opportunity to highlight their results and observations. Our results were shared at Montana State University field day at Towne’s Harvest and Western Ag Research Station, Corvallis, MT, in 2022, 2023, and 2024.

Our farmers and food industry collaborators will continue to be involved in developing and delivering the educational material through their involvement during the project. We will continue to share and discuss the project results with growers during field days and growers' meetings.

Objective 1. Develop and deliver an off-campus education program to enhance the sustainability of vegetable farms.

Information on ecologically based crop production practices has helped vegetable producers make informed management decisions considering labor availability, production aims, and economic goals. With our collaborators, direct communication with our audience was conveyed through presentations in workshops, field days, and stakeholder meetings. At Montana State University, during the summer and fall of 2022, 2023, and 2024, Towne’s Harvest Garden hosted four annual field days where we highlighted different aspects of the project with presentations by Emma Kubinski, researchers, and collaborators. We have also presented our results at the Western Ag Research Station 2023 and 2024 Field Days. In addition, Towne’s Harvest Garden provides weekly tours of the farm and hosts a community-supported agriculture (CSA) program that connects community members and home gardeners. During these tours, they visited our research plots and received information on weed management in carrots.

We have also had opportunities for outreach through on-farm experiments. Bodhi Farms, one of our collaborators, regularly conducted outreach events to connect with local community members, including a farm-to-table restaurant and Bodhi Farm Club. This organization invites community members to volunteer on the farm in exchange for learning more about farming. Bodhi Farm has an agrotourism focus that encourages people from the surrounding region to learn about agriculture. We used these outreach and educational opportunities to reach the local community via signage. We also discussed research with employees so they could present the research in their own outreach activities. We also shared our study with Camp Bodhi, an outdoor summer kids camp focused on outdoor education and farming held at Bodhi Farms through educational signage.

Lastly, we took the opportunity to share results with a broader audience by presenting them at meetings and conferences. The study results were presented at the 2022 and 2023 Montana Organic Association Conferences and included in round table discussions with producers. Additionally, the study was presented at the 2023 National Weed Science Society of America meeting to researchers in weed management and agricultural stakeholders from across the country. Furthermore, presentations were carried out at Montana State University, including the College of Agriculture Three Minute Thesis Competition and the Land Resources and Environmental Science Research Colloquium in 2022 and 2023. The results of the final study will also be published in peer-reviewed scientific journals such as Weed Research, HortScience, Agroecology, and Sustainable Food Systems. Additionally, results from this research will be featured on the Western Integrated Pest Management podcast series this upcoming winter.

Objective 2. Enhance student active learning on the sustainable management of vegetable farms

Emma Kubinski facilitated undergraduate student-engaged learning on the courses Menalled, Ebel, and Burgess taught at Montana State University. In 2021, MSU Sustainable Food and Bioenergy Systems program undergraduate students participated in establishing the field trial and presented the preliminary results to their peers. In 2021, 2022, 2023, and 2024 this study was presented at several undergraduate-level courses at Montana State University, including Weed Ecology and Management (ENSC 443, Menalled, with Emma Kubinski as TA), Research Methods (HHD 512, Ebel, Emma Kubinski as TA), Food System Resilience, Vulnerability and Transformation (SFBS 466, Ebel and Emma Kubinski as co-instructor), Towne's Harvest Practicum (SFBS 296, Burgess), Vegetable Production (HORT 337, Burgess), and Introduction to Horticulture (HORT 105, Kubinski guest lecture). In the fall of 2022 and 2023, ENSC 443 students had the opportunity to see the experiment in the field to learn about the CPWC. A lab activity was then carried out that consisted of a reduced version of the study in a greenhouse setting that enabled students to connect their results and observations to those witnessed in the field study regarding plant/weed competition.

Furthermore, this project has provided excellent research experience for undergraduate students. An undergraduate research assistant, Kevin Sheridan, took a leading role in the study assessing the impact of CO2 on the CPWC. Kevin participated firsthand in experimental design, implementation, data collection, and analysis. In addition, students Daniel Engen, Andrew Christensen, Reilly Stack, Tyler Kulak, and Meghan Rodriguez have participated in the project's implementation, gaining valuable research experience.

Outcomes of our educational plan include increased knowledge and awareness of our audiences on several topics related to the sustainable production and commercialization of vegetable garden products. These include ecological approaches to managing weeds, the impact of climate change on weed-crop competition, and increased market opportunities through added-value products. While our research focused on Montana, the principles learned in our study reach an audience across the Western USA.

Objective 1. Develop and deliver an off-campus education program aimed at enhancing the sustainability of vegetable farms.

Through various off-campus outreach, hundreds of people learned about our research in sustainable agriculture. Montana State University's research station field days have provided excellent opportunities to discuss results with producers, stakeholders, other researchers, and the public. Towne Harvest Garden has hosted four field days in the 2022, 2023, and 2024 growing seasons. Over the four Towne Harvest field days, over 260 attendants could visit the plots and see results firsthand. In addition, results were presented at the Western Agriculture Research Station in Corvallis, MT, in 2023 and 2024 to over 370 attendees (Figure 9). At both locations, questions, discussions, and feedback were directly received from local growers. Furthermore, Towne Harvest Garden had weekly tours and a CSA where residents were exposed to research plots and projects. Notably, surveys were handed out on field days, and several respondents reported they wanted to apply something new they had learned from the presentation. Others reported learning something new about the timing of cultivation.

Figure 9. Presentation at Western Agriculture Research Station Field Day.

In addition to presentations at Montana State University's Research Stations, we also carried out outreach on partner farms. Due to plots being set up on each partner farm, Amaltheia, Chance Farms, and Bodhi Farms, research was discussed with farmers and farmhands. Additionally, we set up outreach posters at Bodhi Farms, where guests staying for agrotourism and kids participating in Camp Bodhi could learn about the project. Furthermore, growers and agricultural stakeholders also learned about the project during the 2022 and 2023 Montana Organic Association Meetings.

Lastly, results from the study were shared with other researchers at professional meetings. At the 2023 National Weed Science Society Meeting, the project was presented at the three-minute thesis competition. The presentation was given twice due to proceeding to the finalist competition. Over 100 weed science researchers watched the presentation. Furthermore, results were also presented at the three-minute thesis competition in the College of Agriculture, where over 50 graduate students, faculty, and staff watched the presentation.

Objective 2. Enhance student active learning on the sustainable management of vegetable farms

Through the incorporation of this research into various Montana State University classes, including Weed Ecology and Management (ENSC 443), Research Methods in Human and Health Development (HHD 512), Food System Resiliency, Vulnerability and Transformation (SFBS 466), Towne's Harvest Practicum (SFBS 296), Vegetable Production (HORT 337), and Introduction to Horticulture (HORT 305) over 236 students were able to participate in active learning. In SFBS 466 and HHD 512, undergraduate and graduate students learned how to carry out research in sustainable agriculture and similar fields using this project as an example. In both classes, students were allowed to ask questions, discuss how the study was carried out, and apply these concepts to their ideas. Given that both ENSC 443 and SFBS 296 were during the growing season, students visited research plots and could see results from the study in person. In addition, in ENSC 443, results and concepts from the CPWC were used to explain the plant-plant associations, specifically competition. Results and photos from the project provided excellent learning tools for students. Furthermore, a lab was conducted where students set up a similar mini version of the experiment in the greenhouse using pots. Students saw results in their studies and compared them to those in the field. Using this information, students were instructed to write lab reports, using previous findings from the project and peer-reviewed literature to understand better crop-weed competition and how to write a research report.

This project has also provided research opportunities for undergraduate students. As mentioned, undergraduate student Kevin Sheridan took a leading role in assessing the impact of CO2 on the CPWC, participating in experimental design, implementation, and data collection and analysis. Using these experiences, Kevin was awarded the Montana State University’s Undergraduate Scholars Program Research Award. Furthermore, he presented the project at the Land Resources and Environmental Science Research Colloquium. Other undergraduate students, including Daniel Engen, Andrew Christensen, Reilly Stack, Tyler Kulak, and Meghan Rodriguez, have participated in implementing aspects of the projects and gained valuable experience. These opportunities will undoubtedly strengthen their ability to conduct research in sustainable agriculture and similar fields.