Final report for LNE22-446

Project Information

A robust regional seed system is vital to the economic and ecological health of Northeast farming communities. Farmers are increasingly interested in producing seed for personal/community use or as an opportunity to expand production and diversify enterprises, and Northeast seed companies including High Mowing, Fedco and the Hudson Valley Seed Company (HVSC) have interest in increasing sourcing of regionally produced seed. In order for growers to be successful, they need to learn the horticulture and economics of expanding from growing vegetables for food to seed.

Additionally, ancestral communities throughout the Northeast are working to improve the quality and availability of heritage seed varieties in order to successfully preserve culturally-significant seed lineages to increase seed and food sovereignty. Doing so also increases community access to traditional recipes, cooking practices, and traditional gardening techniques.

In order to meet the needs of growers interested in producing seed, we developed a comprehensive online course with synchronous and asynchronous content designed to provide a solid horticultural foundation and create a community of learners. During the winters of 2023 and 2024 growers and seed keepers were enrolled in the recently-developed Organic Seed Alliance (OSA) seed production online course after it was tailored to the Northeast by our content experts. Each week's course materials were complemented by Zoom trainings to address specifics of Northeast seed production, contracting with regional seed companies, and seed economics. Growers were able to meet with mentors monthly throughout the growing season for additional support with specific crop questions. In person field meetings brought learning communities together each year to share experience and see different seed processing systems and equipment.

The research component of this grant focused on examining the utility of protected culture in northeast seed production. We conducted replicated trials comparing seed yield, quality, and profitability from high tunnels versus field culture with a biennial (onion) and annual (lettuce) crop in 2022 and 2023, paired with two non-replicated on-farm sites per season. The research indicated significant benefits to growing these model crops in protected culture.

This project worked with 174 commercial vegetable farmers and 25 ancestral seed keepers over three years to expand production of quality, regionally adapted and culturally significant seed. In the two years in which growers reported on their seed production, they produced $253,000 worth of seed. Ancestral seed keepers from the class improved their techniques for seed keeping and strengthened their network of seed keepers but did not report seed increases.

Sixty-five commercial farmers and thirty ancestral seed keepers will increase the quality, production, and distribution of Northeast grown seed, resulting in $150,000 increased revenue from 4 acres of seed sold to Northeast seed companies and growth of one hundred and eighty pounds of heritage seed for community use.

Farmers are increasingly interested in producing seed for personal/community use or as an opportunity to expand production and diversify enterprises, and Northeast seed companies have interest in increasing sourcing of regionally produced seed. In order for growers to be successful, they need to learn the horticulture and economics of expanding from growing vegetables for food to seed.

Additionally, Native American communities throughout the Northeast are working to improve the quality and availability of ancestral seed varieties in order to successfully preserve culturally-significant seed lineages to increase seed and food sovereignty. Doing so also increases community access to traditional recipes, cooking practices, and traditional gardening techniques.

Growers and seed keepers expressing interest in expanding their seed work were enrolled in the recently-developed Organic Seed Alliance seed production online course after it was tailored to the Northeast by our content experts. This course was offered during January, February and March, and was complemented by a series of Zoom trainings to address specifics of Northeast seed production, contracting with regional seed companies, etc. The local learning communities met monthly with a compensated regional seed mentor as an opportunity to learn from each other and consult with an expert grower. In person field meetings brought learning communities together for on-farm learning.

The research component of this grant focused on determining whether seed production in the Northeast benefits from protected culture. We conducted replicated trials comparing seed yield, quality, and profitability from high tunnels versus field with a biennial (onion) and annual (lettuce) crop in 2022 and 2023, paired with two non-replicated on-farm sites per season.

This project worked with 174 commercial vegetable farmers and 25 ancestral seed keepers over three years to expand production of quality, regionally adapted and culturally significant seed. In the two years in which growers reported on their seed production, they produced $253,000 worth of seed.

Cooperators

- (Educator)

- (Educator)

- (Educator)

Research

Primary: Dry seeded crops produced in the Northeast will have lower disease incidence and higher quality grown under protected culture than in field conditions, and increases in yield and quality of tunnel grown seed will justify the added expense of utilizing high tunnel space.

Secondary: Northeast grown heritage seed currently carries diseases which can be identified through lab testing and mitigated using available techniques, leading to increased quality of heritage seed lines

Primary Hypothesis: Dry seeded crops produced in the Northeast will have lower disease incidence and higher quality grown under protected culture than in field conditions, and increases in yield and quality of tunnel grown seed will justify the added expense of utilizing high tunnel space.

Treatments:

A) High tunnel: Precipitation can be eliminated and soil moisture regulated, ensuring optimal harvest conditions.

B) Open field: A more inexpensive option for most crops, but lacking ability to control precipitation, dew and field moisture.

Year One Methods: We conducted a paired comparison of high tunnel vs field production of two crops: onion and lettuce. The research farm included 3 replicated plots of 85 onion bulbs and 3 plots of 25 lettuce plants in the tunnel and 3 in the field. On-farm research sites in this season only included lettuce because we didn't have enough onion bulbs to send to daughter sites. Each daughter site had 20 lettuce plants inside and 20 outside.

'New York Early' onion bulbs were overwintered in a 34 degree walk-in cooler. Bulbs were nested upright in pine shavings three layers deep. The bulbs were removed from storage and planted on May 15th in a one-by-one foot grid spacing in three rows across a bed. After planting the bulbs were mulched with straw for weed control and two rows of drip were installed for irrigation. Floral netting was installed to support the flower heads as they emerged. Seed heads were fully mature and harvested on August 17th. They were dried on mesh covered benches in a high tunnel and then stored at 65 degrees in a barn until processing.

'Garnet Butter Gem' lettuce plants were seeded in the greenhouse April 29th and transplanted to the field on May 29th. Plots were a single row with one-foot in-row spacing. Lettuce seed was mature and harvested on August 27th. Entire plants were clipped one foot below the inflorescence and dried on mesh covered benches in a high tunnel and then stored at 65 degrees in a barn until processing.

Year One Data Collection:

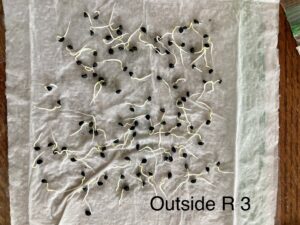

Research farm data collection: At harvest the final plant and seed head count were recorded per plot in onions, and the final plant count was recorded for lettuce. Intact seed heads (onions) and plants (lettuce) were dried in a high tunnel with shade cloth and stored in a dry barn pending seed extraction. All seed was hand-threshed to ensure maximum extraction and to minimize damage. Onion seed was cleaned using hand screens and a Winnow Wizard. Lettuce seed was cleaned using hand screens and an Office Clipper. Final seed weights were recorded by plot. Germination testing was conducted on site using 100 seeds per plot. Seed sub-samples were sent to the Iowa State Seed Lab for testing.

Daughter site data collection: Data from partner farms was not extensive enough to draw meaningful conclusions.

Year Two Methods: We continued the paired comparison of high tunnel vs. field production of two crops: onion and lettuce. The research farm included three replicated plots of 75 onion bulbs and 3 plots of 25 lettuce plants lettuce in the high tunnel and three in the field. Daughter sites were not employed in year two.

'New York Early' onion bulbs were overwintered in a 34 degree walk-in cooler. Bulbs were nested upright in pine shavings three layers deep. The bulbs were removed from storage and planted on May 18th in a one-by-one foot grid spacing in three rows across a bed. After planting the bulbs were mulched with straw for weed control and two rows of drip were installed for irrigation. Floral netting was installed to support the flower heads as they emerged. Seed heads were fully mature and harvested on August 29th. They were dried on mesh covered benches in a high tunnel and then stored at 65 degrees in a barn until processing.

'Italianischer' lettuce was seeded on April 15th and transplanted on May 30th. Plots were a single row with one-foot in-row spacing. During bolting, deer entered the caterpillar tunnel and outdoor plots and browsed many of the flower stalks, resulting in a crop failure.

Year Two Data Collection:

Research farm data collection: Unfortunately, heavy deer browse both outside and in the high tunnel made the lettuce data unusable. At harvest the final plant and seed head count were recorded per plot in onions. Intact seed heads were dried in a high tunnel with shade cloth and stored in a dry barn pending seed extraction. All seed was hand-threshed to ensure maximum extraction and to minimize damage. Onion seed was cleaned using hand screens and a Winnow Wizard. Germination testing was conducted on site using 100 seeds per plot. Seed sub-samples were sent to the Iowa State Seed Lab for testing.

We added a small non-replicated trial in the high tunnel comparing large onion bulbs to small onion bulbs in terms of yield of seed. We wanted to determine if growers needed to cull out small (2-2.5 inch diameter) bulbs compared to the large (3-4 inch diameter) bulbs.

Year Three Methods: We repeated the lettuce paired comparison in year three in a space with deer fencing. Space was limited so we only included 30 plants inside and 30 outside. We included a third year of allium paired comparisons, expanding our examination to shallot to see if there were differences between allium species. Three plots with 30 bulbs each were planted inside and outside. Shallot bulbs were distributed to two daughter sites.

'Ed's Red' shallots were overwintered in a 34 degree walk-in cooler. Bulbs were nested upright in pine shavings three layers deep. The bulbs were removed from storage and planted on May 25th in a one-by-one foot grid spacing in three rows across a bed. After planting the bulbs were mulched with straw for weed control and two rows of drip were installed for irrigation. Floral netting was installed to support the flower heads as they emerged. Seed heads were fully mature and harvested on August 13th. They were dried on mesh covered benches in a high tunnel and then stored at 65 degrees in a barn until processing.

'Garnet Butter Gem' lettuce was seeded on April 20th and transplanted on May 30th. Both indoor and outdoor plots were planted on black plastic mulch in a double row. Between-row spacing was 18 inches, and in-row spacing was one foot. Lettuce was mature and harvested on September 5th.

Year Three Data Collection:

At harvest the final plant and seed head count were recorded per plot in shallots and the plant count was recorded in lettuce. Intact seed heads and plants were dried in a high tunnel with shade cloth and stored in a dry barn pending seed extraction. All seed was hand-threshed to ensure maximum extraction and to minimize damage. Shallot seed was cleaned using hand screens and a Winnow Wizard. Lettuce seed was cleaned using hand screens and an Office Clipper. Final seed weights were recorded by plot.

Data analysis: Data from the research plots were analyzed using two sample t-tests.

Secondary Hypothesis: Northeast grown heritage seed currently carries diseases which can be identified through lab testing and mitigated using available techniques, leading to increased quality of heritage seed lines

Treatments: Laboratory testing

This hypothesis was not tested because ancestral seed keepers were unwilling to send seed to the lab for testing. Our first proposed alternative was to send live plants in for disease testing, but this was also rejected and it was made clear no lab testing was desired. As an alternative, these growers received supplemental education about how to identify diseases in their crops and how to rogue seedborne diseases and administer in-season preventative treatments to reduce disease spread. There is room to expand this work in the future as relationships and trust continue to be rebuilt.

The replicated trial data were our primary source of useful information from these studies.

Year one lettuce trial data from research farm: Data collected included the total weight in ounces of the seed harvested from each replication, the final plant population that survived to harvest, seeds per gram, which provides relative seed size between treatments, and the ounces of seed per plant per replication. We used seed per plant for statistical comparisons. Percent germination is an industry standard measure of quality and essential information for the end user (grower).

Table 1: Year one lettuce trial data

| Treatment | Rep | Weight total (oz) | Final Plant Population | Seeds per gram | Oz seeds per plant | % Germination |

| Indoor | 1 | 14.7 | 23 | 1110 | 0.64 | 96% |

| Indoor | 2 | 14.85 | 23 | 1080 | 0.65 | 99% |

| Indoor | 3 | 12.55 | 24 | 1130 | 0.52 | 100% |

| Outdoor | 1 | 15.5 | 26 | 1220 | 0.60 | 98% |

| Outdoor | 2 | 13.55 | 24 | 1110 | 0.56 | 99% |

| Outdoor | 3 | 11.75 | 25 | 1360 | 0.47 | 99% |

A pooled two-sample t-test was conducted to compare seed yields of lettuce grown indoors versus outdoors. There was no significant difference (p= 0.18) between tunnel grown (mean 0.60 oz per plant) and outdoor grown (mean 0.54 oz per plant).

Seed lab results: Both indoor and outdoor lettuce samples tested negative for the seedborne disease panel that Iowa State uses. Seed test results 2 2023 Seed test results 2023

Germination rates for indoor and outdoor treatments are consistently above the minimum industry standard.

Year one onion trial data from research farm: Alliums make two to three seed heads per bulb, so in addition to collecting the total seed weight per plot and plant population, we also counted the number of seed heads per plot. For yield comparisons, the seed yield per bulb was used.

Table 2: Year one onion trial data

| Treatment | Rep | Weight total (oz) | Final Plant Population | Seed Head Count | Oz seed per bulb | Oz seed per head | Number of seeds per gram | % Germination |

| Indoor | 1 | 32.83 | 83 | 289 | 0.40 | 0.11 | 225 | 94% |

| Indoor | 2 | 29.36 | 77 | 281 | 0.38 | 0.10 | 230 | 98% |

| Indoor | 3 | 22.59 | 73 | 226 | 0.31 | 0.10 | 235 | 98% |

| Outdoor | 1 | 11.66 | 70 | 242 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 250 | 96% |

| Outdoor | 2 | 13.65 | 71 | 249 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 235 | 90% |

| Outdoor | 3 | 12.03 | 71 | 253 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 255 | 99% |

A pooled two-sample t-test was conducted to compare seed yields of onion grown in the tunnel to seed yields grown outdoors. There was a significant difference (p=0.0013) between tunnel grown (mean 0.36 ounces per bulb) and outdoor grown (mean 0.18 ounces per bulb).

Statistical analyses: Onion t test 2023 Lettuce t test 2023

The disease panel from the Iowa State Seed Testing Lab came back negative for all seedborne diseases in both the indoor and outdoor treatments. Onion results indoor Onion results outdoor

Germination rates for indoor and outdoor treatments are consistently above the minimum industry standard.

Images, from left to right: Outdoor onion seed plots after pollination, indoor onion and lettuce after pollination, an outdoor diseased onion umbel, and lettuce seed reaching full maturity indoors.

Images, from left to right: onion umbels drying on insect netting in the high tunnel, onion seed germination test, Natasha hand threshing lettuce seed.

Year two onion trial data from research farm: Data categories collected were identical to data from year one, but the initial and therefore final plot count was slightly lower due to issues with overwintering the onions. A non-replicated comparison of small and large bulbs was included in the indoor plots to provide some initial information for further study.

Table 3: Year two onion trial data

| Treatment | Rep | Weight total (oz) | Final plant population | Seed head count | Ounces seed per bulb | Ounces per seed head | Seeds per gram | Germination % |

| Inside | 1 | 32.9 | 69 | 300 | 0.48 | 0.11 | 220 | 97% |

| Inside | 2 | 39.8 | 72 | 345 | 0.55 | 0.12 | 230 | 90% |

| Inside | 3 | 25.8 | 62 | 294 | 0.42 | 0.09 | 210 | 95% |

| Outside | 1 | 20.1 | 70 | 324 | 0.29 | 0.06 | 260 | 92% |

| Outside | 2 | 23.8 | 70 | 332 | 0.34 | 0.07 | 280 | 92% |

| Outside | 3 | 23.5 | 75 | 338 | 0.31 | 0.07 | 250 | 95% |

| Small bulbs | 1 | 11 | 30 | 125 | 0.37 | 0.09 | 220 | 94% |

| Large bulbs | 1 | 11.3 | 27 | 115 | 0.42 | 0.10 | 200 | 97% |

A pooled two-sample t-test was conducted to compare seed yields of onion grown in the tunnel to seed yields grown outdoors. There was a significant difference (p=0.0067) between tunnel grown (mean 0.48 ounces per head) and outdoor grown (mean 0.31 ounces per head).

Statistical analyses: Onions Year 2

Germination rates for indoor and outdoor treatments are consistently above the minimum industry standard.

Images, from left to right: onion umbels in the tunnel nearing maturity, onion umbels outdoors with significant purple blotch infection, and a diseased onion umbel from an outdoor treatment.

Deer predated the lettuce trial in year two, resulting in a crop failure. Lettuce was replanted in year three.

Year three lettuce trial data from research farm: a miscommunication resulted in the three replications being consolidated in processing, making a statistical analysis impossible. However, the yield of seed indoors was more than double the yield outdoors.

Table 4: Year three lettuce trial data

| Lettuce | Weight total (oz) | Number of Plants | Oz of seed per plant |

| Indoor | 16.64 | 34 | 0.49 |

| Outdoor | 6.56 | 34 | 0.19 |

Daughter sites with allium seed production: Due to issues with onion bulb quality, shallots were distributed to daughter sites in 2024. The number planted varied by farm, and the yield was fairly consistent across sites both inside and outside. Because we only have one year of data and growers used a wide range of cultural practices, this experiment should be revisited.

Table 5: Year 3 shallot trial data

| Lbs Seed | Heads | Bulbs | oz per head | oz per bulb | |

| Indoor 1 | 0.15 | 25 | 11 | 0.10 | 0.22 |

| Indoor 2 | 0.24 | 30 | 15 | 0.13 | 0.26 |

| Indoor 3 | 0.23 | 49 | 15 | 0.08 | 0.25 |

| Outdoor 1 | 0.39 | 114 | 30 | 0.05 | 0.21 |

| Outdoor 2 | 0.46 | 104 | 29 | 0.07 | 0.25 |

| Outdoor 3 | 0.45 | 85 | 26 | 0.08 | 0.28 |

There is no statistical difference between the indoor and outdoor plots in the year three shallot data.

The location of the research plots in year three was not optimal for early season management because the irrigation system was not turned on until the end of May. The shallot bulbs that were outside received rainfall that helped establish them; the indoor plots became very dry during establishment and nearly half of the shallot bulbs failed to survive to maturity.

General discussion:

The timing of rain events during pollination and maturation of dry seeded crops has a significant effect on seed yield but has not, in these experiments, had an impact on seed quality as related to seed size or disease incidence. The onion crop had statistically significant differences in the yield of protected culture versus field grown seed, with the protected culture seed crop yielding nearly double the field grown. We hypothesize that this is because in both years of this study we had rainy periods during bloom time and throughout seed maturation. While we did not see any increase in seedborne diseases due to the precipitation, we did see an increase in botrytis and purple blotch. The botrytis caused individual seed balls in the seed head to abort, and the purple blotch generally weakened the plant during the period of time when it needed to send energy to the seed heads. This key period extended from bloom in mid-June through harvest in mid-August.

The lettuce crop has a slightly shorter critical period from peak bloom to maturity in which precipitation is detrimental, extending from early August to early September in our study. During the first year of our study we had no precipitation during this time, and saw no difference in lettuce yields in protected culture versus outside. However, in the third year of the study we had regular precipitation during this period. The resulting yield loss due to botrytis and failed pollination indicates that protected culture is very beneficial in years with rainfall during the critical period.

We were generally pleased that all seed we tested came back free of seedborne diseases, indicating both that the stock seed we used was disease free and that we did not introduce these diseases during the growing season. We were also pleased that our germination rates were consistently above industry standards, indicating that our methods produced quality seed.

The use of caterpillar tunnels to protect dry-seeded crops from precipitation at key developmental periods results in significant yield increases, particularly in seasons with frequent rain events. In both seasons of our project we saw statistically significant increases in seed yield in our onion seed crop grown in the tunnel. During the first growing season, our yield was double inside the tunnel versus outside. Notably, the tunnel yields are also approximately double the expected yield for onion seed production (1).

Our lettuce seed yield results will benefit from additional years of data collection to better understand likelihood of yield depression based on precipitation. During the first year of the project we had no precipitation while the seed heads were maturing, making indoor and outdoor conditions nearly identical. In year two of the project we had regular rain events for approximately two weeks before seed harvest, which negatively affected seed head development and subsequent yield. Similarly to our onion seed crop, we saw over double the yield of seed in the tunnel as compared to outside when the crop was exposed to precipitation during seed maturation. As is often the case, weather largely determines the need for protected culture. However, when the need for protection is present, the effect is substantial.

1: Knott's Handbook for Vegetable Production, Fifth Edition. Maynard and Hochmuth, 2007. P. 519.

Education

Engagement:

During year one articles were published in The Natural Farmer and Cornell Small Farms Quarterly: TNF article

Outreach was also conducted to previous Seed Conference attendees, through listserves of The National Young Farmers' Coalition, on the OSA Seed Commons, through Cornell Cooperative Extension regional newsletters, and to the Ujaama Collective directly. We successfully recruited 65 commercial growers for the online course and 110 people for the Seed Conference through these channels. Tina Square was able to recruit 20 Seedkeepers for year one of the course through the Intertribal Agriculture Council.

During year two of the project we promoted the project through the Small Farms Program again as well as through additional extension channels throughout the northeast, which increased interest from Rhode Island, Vermont, and Western New York. We were able to recruit 111 participants to the second year of the commercial seed course through these channels. Tina Square was able to recruit 5 additional ancestral seed keepers, and the 2023 cohort remained involved in the project.

Learning:

All participants of the 2023 and 2024 learning cohorts were invited to participate in the bi-annual 2023 Northeast Seed Conference, although attendance of the conference is not mandatory for project participation. The primary goal of conference attendance is to create a cohesive learning community. The first session of the conference can be found here.

Online courses: Two years of the seed course were successfully completed for commercial growers and community seed keepers. Here is an example of one of the live classes.

Although there are two learning cohorts, community seed keepers and commercial producers, many of the learning objectives are similar and related. The following content is similar for both cohorts:

1) Crop planning: students can determine isolation distances to produce pure seed, minimum population sizes, and understand how to integrate seed production with food production.

2) Plant health and seed production: students understand the relationship between healthy plants and healthy seed, and are introduced to horticultural recommendations for each crop. Students learn about critical diseases and control measures in each of the selected crops.

3) Assessing seed crops for quality and maturity: students are able to successfully assess seed maturity, time harvests, and are able to identify seedstock likely to yield healthy, vigorous seed versus seedstock that should be culled.

4) Seed harvest, cleaning and storage: Students are aware of tools and techniques available to make seed harvests more efficient and successful. They understand the optimum storage conditions for different types of seed and how to create these conditions. During year two of the class, research results from the project informed the content of these classes.

Unique to commercial seed growers:

1) Introduction to seed sovereignty: Native American seed mentor Angela Fergusen facilitated discussions with commercial seed growers about issues surrounding seed sovereignty, and ways that commercial growers can honor and respect ancestral seed.

2) Economics of seed production: Growers were introduced to the OSA seed enterprise budgeting tool https://seedalliance.org/publications/seed-economics-toolkit/ and used it complete an enterprise budget on their chosen seeds. They learned about seed contracting from Fedco contractor Emily Pence.

Learning cohorts and mentorship: During both years of the class demand for mentorship was low enough that we were able to consolidate our meetings by crop group. We held bi-monthly mentorship meetings based on crop groups, and Heron and Amirah each established office hours for folks who had specific questions.

Field meetings: During 2023 we held 5 grower demonstration/field meetings in total across 3 states. In 2024 we held 3 commercial grower field meetings and had 3 meetings for ancestral seed keepers.

Evaluation

The primary measure of success is based on each individual’s ability to successfully grow a quality seed crop. We asked each grower to document their plots with photos and weigh the final seed grown and harvested, and record square footage grown. They largely did not send us square footage information, but we do have many photos and most of the growers' final yields and prices if seed was sold. Almost no growers opted to send seed for testing; perceived seedborne issues were far fewer than we anticipated.

Formative assessments were built into the OSA/project online course in order to assess learning during the modules and to highlight areas which need additional attention. A summative (final) assessment was completed at the end of both years of the commercial production course.

Ancestral seed keepers did not create assessments to judge their changes in seed production, and the loss of our project coordinator at the end of year two made rigorous follow-up difficult. We measured success by the number of seed events that were hosted by these communities during years two and three of the project. Seed work was centered in the Intertribal Agriculture Council's Eastern Regional Conference in both 2023 and in 2024; multiple multi-nation seed sharing events were planned in the winters of 2023 and 2024, and we were invited to participate in three educational events that attracted dozens of people each in the winters of 2023 and 2024.

Milestones

Engagement: 1780 growers learn about the project through a release published in the ENYCHP monthly newsletter (750 subscribers, November ‘22); the Cornell Vegetable Team Newsletter (900 subscribers, November ‘22), and as direct outreach to previous seed conference vegetable session attendees (130 growers, November ‘22). Growers receive invitations to participate in the Northeast Seed Conference to kick off the project. 80 growers from these groups do so, and an additional 20 learn about the project while at the conference (January 2023). 30 ancestral seed keepers are invited to attend the Seed Conference; 20 are able to do so.

Status: Completed

Year one accomplishments: 1780 growers learned about the project through the ENYCHP monthly newsletter, 39,000 learned of it through Small Farms Quarterly, and 19,000 learned of it through The Natural Farmer. We decided to cap year one participation at 65 commercial growers and have 20 ancestral seed keepers are participating. We had a wait list for 2024.

Year two accomplishments: We once again promoted the course through the Small Farms Program (e-blast) and shifted our other outreach to extension channels in Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and through MOFGA in Maine. We had 111 growers registered for the seed course this year. The Ancestral Seed Course recruited an additional 5 participants and rolled the 20 existing participants into a second year of programming.

2) Learning: 100 commercial growers attend project orientation and networking sessions at the 2023 Northeast Seed Conference, learning about the scope of the project and deciding whether participating is a good fit. 20 seed keepers attend networking events, strengthening seed community ties.

Status: Completed

Accomplishments: 110 growers attended orientation sessions. 10 seed keepers attended networking sessions.

The 2023 Northeast Seed Conference hosted by NOFA-NY had both seed course participants and non-participants. The session attendance was as follows:

- Human Perspectives on Seed – 110 attendees

- Grower Roundtable on Seed Production – 100 attendees

- Seed Economics – 85 attendees

- Overview of the Seed Production Course – 60 attendees

The recordings of the conference were uploaded to the Course site for folks who couldn’t attend the conference to watch (note that the links are included above).

View counts of the recordings

- Human Perspectives on Seed – 63 views

- Grower Roundtable on Seed Production – 60 views

- Seed Economics – 58 views

- Overview of the Seed Production Course – 20 views

The seed conference survey results indicated that growers found the sessions to be very informative and helpful, as well as inspirational. Feedback was overwhelmingly positive and these sessions set the stage for an energized cohort to enter the course.

3) Learning and Evaluation: 65-80 growers and 30 seed keepers participate in the OSA online course (February-March 2023). 65 growers and 30 seed keepers commit to growing seed crops as part of the project, select crops, and are assigned learning cohorts (March 2023). Key knowledge gains which will be assessed via survey in commercial growers following the course: crop planning, plant health and seed production, assessing seed crops for quality and maturity, cleaning, harvest, and storage of seed crops, economics of seed production, contracting, and an introduction to seed sovereignty.

Status: Completed

Year one accomplishments: 65 commercial growers completed the course in year one. 20 seed keepers completed the course. All surveys are posted below.

During the market farmer course live meetings, we had the following attendance:

- Crop planning and reproductive biology - 63 participants

- Seed production basics and crop group breakouts – 58 participants

- Plant and soil health for seed production – 53 participants

- Assessing seed maturity, harvest and post-harvest drying – 53 participants

- Seed cleaning and storage – 47 participants

- Seed sovereignty, seed security and intellectual property rights – 43 participants

- Viable livelihoods in seed production – 40 participants

- Seed course wrap up session - 35 participants

We had participants who were entirely asynchronous due to schedule conflicts and were able to watch recordings and participate on the course forums.

Recording numbers

- Crop planning and reproductive biology – 2 views

- Seed production basics and crop group breakouts – 4 views

- Plant and soil health for seed production – 10 views

- Assessing seed maturity, harvest and post-harvest drying – 11 views

- Seed cleaning and storage – 4 views

- Seed sovereignty, seed security and intellectual property rights – 2 views

- Viable livelihoods in seed production – 3 views

- Seed course wrap up session – 2 views

We used the survey information to fine tune our content for the 2024 course, and to make the decision to offer nearly the same course in year two and allow year one participants to take it again in order to access the same topics more deeply. We heard consistently that a lot of information was being provided, and that hearing it more than once would be beneficial.

Year two accomplishments:

4) Learning: We had proposed dividing the group into annual and biennial learning cohorts, but after learning about biennial production nearly everyone opted to grow an annual. The few folks doing biennials received one-on-one consultation. Annual seed crop producers were invited to begin monthly cohort meetings by major crop type with their mentor starting in April 2023 for year one growers and in April 2024 for year two growers. Ancestral seed keepers met with their mentor as a large group, and did individual consultations.

Status: Completed

Year one accomplishments: We taught information about both annual and biennial seed crops during the course, and offered one-on-one mentorship and guidance to biennial growers in the winter and spring.

During the course of the growing season mentorship was provided for participants growing seed crops. Online Zoom meetings were held twice a month to answer questions by crop family and one-on-one mentorship was also provided. We had 114 attendees in total in mentorship sessions over the summer.

5) Evaluation 2023: At the beginning of the 2023 growing season ancestral seed keepers with heritage seedstock will submit samples for lab testing to determine if any seedborne diseases are present. Appropriate control strategies will be employed, and samples will be taken during the last year of project seed is grown (either 2023 or 2024 - most seed keepers have committed to two seasons growing the same crops). Changes in disease incidence will be a measure of project success. Additionally, all participants will use photos to document their progress and will record the total amount of useable seed produced each season. Ancestral seed keepers will work with their mentors to develop any other useful metrics for the project. Commercial growers will report marketable seed produced and total seed sales."

Status: Completed, with modifications below

Year one accomplishments: After learning about how seed testing worked, none of the ancestral seed keepers opted to use this service. They felt that the testing was too obtrusive to the seed, and were distrustful of the seed labs, fearing that their seed would be stolen. Participants did learn about diseases that their crops may carry in seed, and about plant diagnostic clinics where they could send plant material to have it tested as an indirect measure of seed infestation.

Rather than quantifying disease or even seed quantity, this cohort measured success by the number of additional seed-related events that were created or expanded on through the networking of this group of people. Seed swaps were initiated in Western NY, Central NY, and Northern NY, and in Massachusetts. I was invited to speak at 2 seed related meetings in 2023: Once building seed screens (17 sets) with a community group, and once to talk about seed saving more generally. Tina and Angela were present at all other events.

The commercial seed group shared their seed yields through surveys and we collected contract information. 2023 and 2024 numbers are reported below in Milestone 7.

6) Learning: During the winter of 2024 additional commercial growers were invited to join the project and take the 2023 online course asynchronously. Ancestral seed keepers continued into a second year of online class, included more cohort sharing, resource sharing strategies (seed cleaning and harvesting equipment ideas), and advanced seed production topics such as the continuation of disease management, scaling up seed production, and other topics identified by the learning cohorts. In-person winter meetings were organized in New Hampshire for commercial growers and in the Oneida Nation for ancestral seed keepers.

Status: Completed

Learning and Evaluation: 110 growers actively participated in the OSA online course (January - March 2024). 110 growers commited to growing seed crops as part of the project (February 2024). Key knowledge gains which were assessed via survey in commercial growers following the course: crop planning, plant health and seed production, assessing seed crops for quality and maturity, cleaning, harvest, and storage of seed crops, economics of seed production, contracting, and an introduction to seed sovereignty.

Status: Completed

Year two accomplishments: 110 commercial growers completed the course in year two. All surveys are posted below.

During the course live meetings, we had the following attendance:

- Introduction to course, expectations and meeting mentors and other students - 92 participants

- Introduction to crop reproductive biology - 86 participants

- Seed contracting (optional session) - 58 participants

- Seed production basics - 70 participants

- Mentorship group breakout sessions - 77 participants

- Soil and plant health for seed production - 67 participants

- Assessing seed maturity, harvest and post-harvest drying - 50 participants

- Seed cleaning and storage - 53 participants

- Viable livelihoods in seed production - 54 participants

- Seed sovereignty, seed security and intellectual property rights - 52 participants

- Course wrap up and season plans - 44 participants

We had participants who were entirely asynchronous due to schedule conflicts and were able to watch recordings and participate on the course forums.

Recording numbers

- Introduction to course, expectations and meeting mentors and other students - 32 views

- Introduction to crop reproductive biology - 30 views

- Seed contracting (optional session) - 32 views

- Seed production basics - 22 views

- Mentorship group breakout sessions - 13 views

- Soil and plant health for seed production - 4 views

- Assessing seed maturity, harvest and post-harvest drying - 3 views

- Seed cleaning and storage - 2 views

- Viable livelihoods in seed production - 2 views

- Seed sovereignty, seed security and intellectual property rights - 2 views

- Course wrap up and season plans - 3 views

Accomplishments: The year one cohorts indicated that returning to the same course for another year allowed them to deepen their learning more effectively than adding additional material at this point. Additionally, we had over 20 people on a commercial grower waiting list from 2023. Based on these two factors, we ran a modified version of the same course in 2024. We decided to open the course up to more educators and support staff who are looking to learn about seed production but who do not require mentorship. In total we had 95 new commercial growers enrolled, about 15 returning members, and about 20 educators, flower farmers, and beginning farmers enrolled. We encouraged the commercial growers to grow a commercial seed crop and others to take on smaller community projects which are still impactful but not commercial.

The Ancestral Seed Keeper group took a similar approach, adding 5 participants to the cohort and keeping the existing content. They prioritized developing a network of seed keepers, and had many educational events including seed keeping sessions at the Intertribal Ag Council regional meeting (CT) and at Seed Bees in Western NY, Central NY, and Northern NY. Natasha and I were again invited to participate in some of these events, including a community seed saving workshop with 60 attendees, another Earth Day event with 32 visits to our table to see hand-scale cleaning tools, and a fall Seed Summit with 30 attendees.

It was clear that we would have additional funds in our participant support line item even with the additional in-person meetings, so when we were approached by the farm at the St. Regis Mohawk reservation about cooperating on a white corn grow-out, we viewed this as an opportunity to conduct a season-long project with the farm. We planned to learn to better grow Iroquois White Corn from participant farmers, and we were able to share some organic farming practices not yet being used at Mother Earth Farm, including growing corn from transplants, increasing the fertility through soil test recommendations, and using tarps preceding planting for weed control.

Throughout the season we shared the progress of the corn and compared it to corn being grown on the reservation, and made plans for management together. In mid-September (one month ahead of direct seeded corn), farm members came down and harvested the corn, which was then dried and will be used for seed this year.

In coordination with this grant, Jean-Paul Courtens received a SARE farmer grant to create a mobile seed processing trailer. The trailer began touring the northeast last year, stopping in 5 locations. The effort continued in 2024, with 5 additional field days. These field days allowed for community building, hands-on education about key topics, and efficient seed cleaning.

One in-person winter meeting was held at the NOFA winter conference in January 2024. Approximately 40 people were in attendance, including some folks not yet involved in the grant. One seed session was included in the December 2024 New England Fruit and Vegetable conference as well, with 65 people in attendance.

7) Evaluation 2024: Commercial growers documented their progress with photos through the season, and shared marketable seed weight and sales at the end of the season. At the end of the project, commercial growers completed a survey which assessed knowledge gains and asked about future plans for seed growing (acreage and anticipated revenue). Ancestral seed keepers did not share seed weights; we again measured success by the number of meetings held and the number of attendees at these meetings.

Status: Completed

Accomplishments: Many growers uploaded photos of their seed crops, but the key metric here is the marketable seed value. We were highly impressed by how much seed was produced, and were pleased that much of it went into on-farm and community use. The values used in our calculations are for retail seed, but it was noted when a crop was in fact wholesaled. The retail value represents the real value increase in regional seed generated by the project, and we felt like this was an accurate number to use. All of the seed crops and their values are linked in the Production Data document. The course summary provides a broad overview of the parts of the course participants found most useful each year.

As mentioned, the Ancestral Seed keepers did not want to share data on their seed, and success was measured by community building and a measured increase in the number of seed-centered events in their communities.

SARE Seed Production Course Summary

8) Engagement, Learning: 3-4 commercial seed growers or seed keepers will present about the project during the January 2025 Northeast Seed Conference, providing information for other aspiring seed producers and demonstrating their own skillbuilding.

Status: completed

There was no Northeast Seed Conference, so this deliverable was moved to the New England Fruit and Vegetable Conference. 65 farmers were in attendance and the event generated a great deal of excitement to include more seed programming in the conference in the future.

Milestone activities and participation summary

Educational activities:

Participation summary:

Learning Outcomes

Performance Target Outcomes

Target #1

65

Will increase the quality, production, and distribution of Northeast grown seed.

Resulting in 4 acres of seed produced

And $150,000 increased revenue from sales of seed

57

Will increase the quality, production, and distribution of Northeast grown seed.

Producing $253,000 in regional seed

On approximately 4 acres-- plots were very dispersed and hard to quantify accurately.

The commercial seed production courses were measured through changes in knowledge first, using in-course and post-course surveys that have been included in the narrative. At the end of the course a follow-up survey was administered to determine how many people successfully grew a seed crop and what happened to the crop. We know that some people who grew a seed crop did not complete the survey, so even though we met our benchmarks, the actual production is higher.

Getting our ancestral seedkeeper cohort's feedback was difficult in large part because our program lead in that effort, Tina Square, took a different position and was unable to complete the interviews and personal feedback collection that was planned before departing. We were able to complete 3 additional community meetings with Native American farmers with the cost savings from hosting online instead of in person meetings regionally, and had strong attendance at each, indicating good community interest in seed keeping. Independently organized regional meetings including the 2024 Intertribal Ag Council regional meeting in Connecticut included seedkeeping sessions which included members of our seedkeeping cohort, showing amplification of our efforts.

Our research shifted away from disease assessment with both the commercial growers and ancestral seedkeepers because of a general reluctance to have seed sent to the lab for testing. We had one grower who sent seed in for testing have it come back positive for bacterial speck after her plants looked suspect. However, most growers felt that their plants were healthy and opted not to send seed for testing. Ancestral seedkeepers declined on principal, as discussed in the narrative. All seed from the replicated trials was sent for testing and was disease free.

The partnership between this grant and Jean-Paul's farmer grant was a clear success. Having 4-5 meetings each year advertised to the seed class cohorts where they could experience the cleaning equipment helped them understand what was possible and how to overcome the largest barrier to seed production, which is cleaning. At least 2 seed production hubs are being formed or expanded in the Northeast because of this partnership.

Additional Project Outcomes

We received an OREI grant to work on seed agronomy as part of a national group. This work began in September of 2024 and will run through 2028.

A SARE farmer grant that ties directly to this work was funded and the project is benefiting participants.

I have never received as many positive notes from people as I have from this project, which I believe shows how much people wanted this particular information and were ready to move forward and make positive change. People continue to send updates even though the course is completed, including those like this one last week:

"I have finalized contracts with Sow True and Two Seeds in a Pod to grow herb seeds for them this season. Marshmallow and Skullcap for Sow True and Borage, Sweet Marjoram, and Winter Savory for Two Seeds in a Pod. So THANK YOU for the wonderful class in 2024 - I believe it's given me the tools that I need to do this. Super anxious but psyched to do this."

Many course participants plan to keep growing seed for personal, community, and contract use. Our representative from Fedco said of the experience, "On my end it was great overall. Communication was easy last winter/ spring with setting up contracts and most growers were successful. This course has been a huge benefit to Fedco and I am grateful for all the work you have both done to make it happen."

We have had two course participants in Massachussetts begin the process of creating their own local seed companies, which is a remarkable and unexpected outcome of the project. Being connected with a cohort of seed growers makes the sourcing for this endeavor possible.

On a personal level, our farm (Philia Farm) will continue to host the Mohawk with a white corn grow out every year. That partnership was extremely meaningful to us, farming here on ancestral Mohawk land.

Additional agronomic studies to determine potential yields for seed crops are desperately needed. This is the focus of the OREI grant, which is now funded and will be starting this year!