Final report for ONE20-364

Project Information

Commercial swine farms in Northern New England (NNE) are adapted to the environmental and economic conditions of this region. Some of these swine herd management adaptations are recognized as “high risk” in the context of infectious disease biosecurity for swine. For example, NNE swine herds are most commonly raised outdoors where they are likely to have contact with wildlife; commercial hog diets are supplemented with human food waste products; swine herds are comingled with other livestock species on the same premises and agritourism opportunities are realized with minimally restrictive farm visitation policies. We proposed that unrecognized infectious disease threats play a critical role in NNE swine producers' low-biosecurity approach to herd management, rather than a lack of awareness of biosecurity principles.

In this project, we used a series of surveys and on-farm audits to record and analyze the NNE commercial swine industry demographics and management practices including philosophical and actual approaches to farm biosecurity. We conducted virtual and onsite farm-specific training for participants in biosecurity management and documented improvement in biosecurity practice through post-intervention surveys. To increase the value of the biosecurity training, participating swine herds were sampled for an array of endemic infectious diseases of swine. These results provided immediate feedback to the participant about their herd’s current health status and vulnerabilities, which was intended to prompt greater “buy in” to the biosecurity teachings of this study. 50% of participants report that they have increased their biosecurity preparedness as a result of their participation in this study. These project interventions were most successful at influencing partner farmers’ biosecurity behaviors in the areas of: farm visitation policy, livestock quarantine procedures and manure/mortality management.

Project updates and distribution of products developed during this study were presented at multiple venues throughout the study period. This enabled the study team to reach a wide audience, including private practice and regulatory veterinarians, Cooperative Extension agricultural service providers, swine farmers, livestock producers other than swine farmers and farm interns.

The primary objective of this project was to document, analyze and improve the management of Northern New England swine farms relative to infectious disease biosecurity practice. Participating farmers were trained on effective principles of biosecurity tailored to their farm’s infrastructure and goals.

The secondary objective of surveying the regional swine herd for endemic infectious disease was intended to provide the basis for creating outreach materials for preventative herd health management. The results of individual herd disease surveillance studies reinforced the importance of biosecurity practice on that farm and the collective results provide accurate, regionally specific disease prevalence information to industry support groups such as veterinarians, Cooperative Extensions and Departments of Agriculture in Northern New England.

Participating farmers have developed the tools necessary to maintain or improve their swine herd’s health and productivity, even in the face of emerging and endemic diseases. These farmers are armed with known methods for preventing locally identified infectious diseases and possible, future Foreign Animal Disease (FAD) introductions. Lastly, the results of this study may be utilized to provide an accurate representation of the Northern New England swine herd and may serve as a model for use in other states or for expanding disease surveillance activities in the region as may be supported by future funding opportunities.

African Swine Fever is an emerging Foreign Animal Disease (FAD) currently circulating in Europe and Asia. According to the OIE’s March 26 2020 report (1) , over 42,000 pigs were lost in Asia alone over a two-week period, with wild boar and backyard swine playing a significant role in the epidemiology of this disease. The North American hog industry is bracing for the possible introduction of ASF and is actively looking to mitigate current risk sources, including feral and backyard or "transitional" swine. In this context, the Northern New England swine industry may be regarded as a threat to the biosecurity of the national swine industry. This is because the management style of Northern New England swine production is classified as "transitional" and commonly features outdoor-housed pigs, feeding of food waste products and contact between swine herds and wildlife and other livestock species. This management style is in conflict with the recommended biosecurity practices which are already in place in the larger confinement hog industry.

In addition to minimal implementation of preventative biosecurity practices, it is generally uncommon that smaller scale hog producers seek a specific cause of herd production loss through diagnostic investigation. This results in a lack of awareness surrounding the specific infectious disease threats in our region, possibly contributing to the perception that biosecurity practice is not a crucial component of successful livestock management. A compounding factor to this situation may be that of the 53 veterinary practices on the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry (ME DACF) Large Animal Vet List, only three identify swine as a species their business services. More evidence of this apparent lack of veterinary support has come from swine producers requesting consults from the DACF on general animal management issues despite services from the Department being regulatory in nature. A 2019 survey (2) of transitional (outdoor) swine herds in New York State confirmed that producers generally feel that skilled veterinary support for their swine operations is limited.

The USDA National Animal Health Monitoring System (NAHMS) reported several concerning trends with respect to swine health and management on small swine farms in the Northeast. (3). The report describes “Despite porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) being widely dispersed throughout the swine industry, no operations … reported a known or suspected problem with the disease in sows, gilts, or weaned pigs…Nearly 10 percent of operations ... did report difficulties with Mycoplasma pneumonia in their weaned pigs. Perhaps there is some confusion between the two diseases, since about 50 percent of all operations reported no familiarity with PRRS.” This is a concerning conclusion because this chronic viral disease of pigs may be more prevalent than producers are aware of, aiding its spread in our region and continued negative impact on the productivity and welfare of swine. Alternatively, with little exposure to PRRS virus symptoms and disease control measures, the swine industry in this region is unprepared to recognize and respond quickly to an introduction of this virus.

Diseases of high consequence that are not yet present in Northern New England or the United State are preferentially responded to with effective preventative action. Our solution will provide swine producers and veterinarians access to regionally specific swine disease prevalence information and biosecurity education to aid development and adoption of an affordable, effective preventative health care plan for their herd.

Cooperators

- (Researcher)

- (Educator)

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

Research

Objective 1: Farm Biosecurity Evaluation and Farmer Training

Recruitment and surveying

The initial study period (September-October 2020) was spent designing the study survey and creating the partner farmer enrollment forms. These forms were drafted in alignment with the State of Maine’s liability policy and fiscal procedures and with Northeast SARE's requirements.

A list of prospective partner farmers was compiled based on historical collaboration with Cooperative Extension staff in Maine and New Hampshire, private practitioner recommendation, regional industry group recommendation and internet searches for “pastured pork producers” in Maine and New Hampshire. In total, 32 farmers were sent an email to invite interest in participating in the project, with a follow up phone call if an email response was received. Most farmers were busy and appreciated the follow-up calls to further explain the project and build context for this study. Phone communication proved a more successful method of contact for most farmers, likely due to the overwhelming volume of emails received on a daily basis. The initial period of enlistment was October through December 2020. From this enrollment effort, 14 partner farmers were recruited though four of these enrolled farms ultimately declined to complete the entire project. Reasons for dropping out included time constraints, privacy related to herd health concerns, a family medical emergency, and unknown due to a failure to return communication.

Project enrollment forms and the first two surveys were delivered electronically to participants in a single email to condense the number of contacts required of the partner farmers and improve the rate of response. The study surveys were delivered using Google Forms (13) or in hard copy (1) as each partner farmer preferred. The first survey distributed was a Participant Farm Profile, intended to capture information about the size and management of each farm. The second survey was the Farm Biosecurity Profile, intended to assess initial biosecurity knowledge and practice. The responses to these surveys demonstrate the current level of biosecurity practice implemented on their farms and elucidate participant’s current understanding of and attitude towards farm biosecurity concepts.

Participant training

Preliminary results of the project's first two surveys were analyzed in December 2020 in collaboration with representatives from the University of Maine. This discussion focused on how best to summarize the data received via survey response and what valuable correlations may be identified. A secondary takeaway from this meeting was a discussion of how to use survey responses to shape the content and delivery style of the project's Biosecurity Training webinar. For example, no farm reported having a written biosecurity plan so this item was incorporated into the design of the webinar. This initial analysis also endeavored to determine if biosecurity practice as reported by study participants is directly related to biosecurity knowledge, or if producers are aware of more biosecurity principles than they report practicing. With this information we planned to isolate which biosecurity practices are commonly accepted and identify barriers to those recommended practices which are not.

The Swine Health and Biosecurity webinar was developed collaboratively by the Maine DACF research team and University of Maine partners. Representatives from the University of New Hampshire Cooperative Extension and the New Hampshire Department of Food and Markets were invited to attend the webinar. The seminar was delivered via electronic meeting (Zoom) in January 2021, during which participating farmers remained anonymous while tuning in and contributing answers to audience poll questions throughout the event. The webinar content included a summary of the project's introductory survey results, presented as a collective summary so as not to identify any individual partner farmer. The remainder of the webinar focused on biosecurity training for a lay person audience. The presentation introduced 5 major livestock disease transmission routes using examples relevant to northern New England swine farms followed by specific examples of how to implement basic biosecurity principles to mitigate disease introduction via these pathways. Partner farmers completed live "poll" questions throughout the webinar to gauge their understanding of the information presented, to gather more detail on some of the trends highlighted in the study's first two surveys, and to capture changes in opinion or learning. Prior to the webinar, all participants were mailed hard-copy biosecurity plan templates and sanitation guidance for note-taking during the presentation. Electronic copies of these resources are included below:

- Disinfectant Use Charts – from the Center for Food Security and Public Health colorful charts on “Characteristics of Selected Disinfectants” https://www.cfsph.iastate.edu/Disinfection/Assets/characteristics-of-selected-disinfectants.pdf and “The Antimicrobial Spectrum of Disinfectants” https://www.cfsph.iastate.edu/pdf/antimicrobial-spectrum-of-disinfectants

- Biosecurity Plan Template – fillable pdf format from the Healthy Farms Healthy Agriculture website https://www.healthyagriculture.org/prevent/biosecurity-plan/

- Checklist for Outdoor Pigs – from Secure Pork Supply ”Self-Assessment Checklist for Enhanced Pork Production Biosecurity: Animals with Outdoor Access (2109)” https://www.securepork.org/Resources/SPS-Biosecurity-Checklist-for-Animals-with-Outdoor-Access.pdf

A copy of the Northeast SARE Swine Biosecurity webinar slides is provided in the Outreach section of this report. The presentation was recorded and posted for public reference on the DACF Animal Health Division website.

On-farm biosecurity evaluations

The field study phase of this project included a real time observation of each farm's biosecurity management practices. Partner farmers were interviewed using the Biosecurity Assessment template from the Healthy Farms Healthy Agriculture website: https://www.healthyagriculture.org/prevent/biosecurity-plan/. Though several outdoor swine biosecurity audit forms where available, the HFHA form was chosen because of its extensive investigation of common farm management practices characteristic of small farms in the Northeast. Ultimately however, we found that the HFHA assessment tool was too long and contained redundancy that did not enhance the value of the audit. The length of the survey made it cumbersome to fill out in the field.

We completed the HFHA evaluation through a combination of candid conversation and observation of each farm's management style along with structured conversation guided by the survey questions. The evaluation phase worked well as a two-person endeavor: in general, one investigator led the structured assessment by asking the survey's questions at the appropriate site on the farm and the other prompted the farmer to offer more information on their management style. This portion of the visit took from 1 to 2 hours, based on the interest and time constraints of the farmer being interviewed.

Most partner farmers seemed to remain interested in this audit process and used it as a learning tool, asking questions of the researchers and seeking feedback on current or planned farm management practices. During these conversations, we refrained from making specific herd health recommendations such as vaccination plans, instead focusing more broadly on farm infrastructure and management goals that would improve overall farm biosecurity. These farm-specific comments were captured as a typed addendum to each farm's complete HFHA audit form. The addendum and completed audit were provided to each participant within 7-10 days of the site visit.

Before leaving each farm, the participant farmer was presented with a supply of basic biosecurity tools intended to help them implement the recommendations discussed with the research team. This biosecurity tool kit included: signage indicating authorized parking areas and restricted access areas, two boot wash tubs and long handle bristle- brushes, and where relevant, weather resistant public health signage educating farm visitors on disease prevention practice.

Measuring farmer learning and management changes

A final, "post-intervention" biosecurity survey was developed by the main research team with critical input and review from our collaborators at the University of Maine Cooperative Extension. This survey aimed to capture feedback on the utility of the biosecurity training webinar, educational materials provided and the on-farm biosecurity assessment and report. This final survey also solicited feedback that would indicate changes in participant learning and farm management practices. The survey was delivered electronically via the same Google Forms format as the study's first two surveys. This final biosecurity survey was delivered to partner farmers to complete no sooner than four (4) months after their site visit to allow time for consideration and implementation of the research team's recommendations.

Objective 2: Infectious Disease Surveillance Study

Swine herd disease surveillance study

On-farm biosecurity assessments were paired with sample collection for infectious disease surveillance in participating herds. The results of the disease surveillance project were intended to reinforce biosecurity training concepts by providing a tangible and relatable point of reference. Testing for all participating herds was conducted between January and July 2021. Direct phone calls were made to each participant to ascertain:

- designated parking areas,

- comfort with use of the snare to restrain pigs,

- explanation of risks involved in the blood sampling procedure

- permission for photos and video and

- approval of attendance of other veterinarians.

A reminder email was sent to the participant within 5 days of the visit to confirm the time and personnel involved as well as any recent concerns for COVID-19 exposure.

Site visits averaged 3-4 hours, influenced by the degree of containment of the animals, amount of animals tested and number of people available for assistance. Supplies required for surveillance sampling included:

- 16 G x 4 inch needle with 12 cc disposable syringes

- Red top blood tubes (no additive)

- Sterile synthetic (dacron) swabs (2 per animal)

- Rectal swab vials: 5 samples/pool in 5 cc phosphate buffered saline

- Tonsilar swab vial: 5 samples/pool in 5 cc phosphate buffered saline

- Fecal sample vials

- Commercial hog snare

- Commercial hog oral speculum (large)

- Collapsible metal camp table

- Sharps container

- clean coveralls (machine washed and dried on high for a minimum of 20 minutes)

- sanitized boots soaking in disinfectant solution (Virkon)

- disposable nitrile gloves

- ear plugs, eye protection

- log book

- Styrofoam cooler and frozen ice pack

Sampling focused on mature swine as defined by attaining the age of 4 months or greater, with a preference for those herd members identified as "breeder swine" due to their presumed longevity in the herd's population. Mature swine were the preferred sample group as they would be more likely to reflect the herd's stable disease profile through serology testing. In all herds, any pig meeting the age requirement was included in the surveillance group as all herd sizes were small enough to prevent excluding any eligible animals. This resulted in a maximum of 23 pigs and a minimum of 9 pigs sampled at a single site. The cumulative sample size (185 pigs) fell well short of the projected 300 pigs intended; however, this sample size is still statistically valid based on an assumed average disease prevalence of 2.00% and a statewide inventory of 4700 hogs (NASS 2014) according to the USDA Sample Size Calculation Matrix.

Animal handling and sampling collection was performed in accordance with industry standards and protocols for USDA program disease surveillance. At no point were the animals involved in the study removed from their farm of origin or under the care of the study investigators. Pigs for sampling were confined in small groups or singly in the smallest space possible within the available infrastructure. To safely snare one pig in a group of pigs, the farmer and others were enlisted to use pig boards to manage interference from the other animals. This protected both the sampler and the contained animal. If a sow was nursing piglets, she was removed from their area before attempting to place the snare. The snare was applied to the upper portion of the snout and secured behind the canines. The snare was operated by a member of the research team or handed off to the animal owner in cases where they wished to participate. Care was taken to apply steady back pressure in a manner that safely controlled the animal and positioned the head for safe and successful blood collection.

- 10 cc of blood was collected from the jugular vein or vena cava and was allowed to clot at room temperature for 1-3 hours.

- Rectal swabs were collected by rotating the dacron swab against the rectal lining and collected into pooled sample tubes, 5 pigs per submission.

- Nasal swabs were collected by insertion of dacron swabs into the nares and rotating the head of the swab firmly against the lining of the nasal cavity. Both nares were sampled and swabs were collected into pooled sample tubes, 5 pigs per submission.

Test sensitivity was increased for the final 7 herds by adapting the nasal swab technique through use of the oral speculum and collecting tonsillar swabs instead. The oral speculum was inserted under the upper canines and rotated downwards against the lower jaw to leverage the mouth open for access to the soft palate. The head of the swab was scraped firmly across the tonsillar area and samples were pooled 5 animals/ collection jar. Rectal swab and nasal/tonsillar swabs were agitated in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), the swab was discarded and the inoculated solution was stored on ice (chilled, not frozen). A fresh, environmental fecal sample was collected to represent the intestinal parasite exposure of the sample group. Approximately 10 grams of fresh fecal material was collected into a clean 20ML sample collection jar and stored on ice (chilled, not frozen). All samples were labeled with the sample type, farm name, date of collection and individual animal ID. These ranged from animal names, identifying characteristics, ear notch numbers, farm management ear tags or official ID ear tags. Samples were delivered to the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry State and Federal Diagnostic Lab for storage and subsequent shipment to the Iowa State Veterinary Diagnostic Lab. The diseases and test types included in our final surveillance program were:

- Lawsonia intracellularis ELISA,

- Influenza A Virus NP ELISA,

- PRRSV x3 ELISA,

- M. hyopneumoniae PCR,

- Circovirus INgezim,

- Brachyspira SD Screen PCR,

- TGEV/PRCV Differential ELISA,

- APP ApxIV ELISA,

- M. hyorhinis IgG ELISA,

- Fecal Float

Results from each herd surveillance testing effort were generally available within 7-10 days. The report from the Iowa State Veterinary Diagnostic Lab was delivered by email to the participant farmer along with the HFHA audit and farm-specific recommendations addendum. Participants were interested in discussing the surveillance testing report and these conversations ranged from 30 minutes to 2 hours. Questions regarding disease ecology, treatment and vaccine options and requests for referral for a farm veterinarian were the most common topics visited in these discussions. Most participants verbalized appreciation for the information and time spent both on the farm and in the follow up discussion.

Herd surveillance data was collected into a single table to reflect the prevalence of these targeted diseases on a population level. The collectivized information prevented identification of any one participant farm and suggested regional herd health characteristics that are distinct from those known about commercial swine herds in the Midwest. This collective information was presented to regional groups at conferences, continuing education events and producer group annual meetings.

Objective 1: Farm Biosecurity Evaluation and Farmer Training

PRE-INTERVENTION SURVEYS

Fourteen partner farmers enrolled in the project and completed the initial surveys. Four participants did not complete all components of the project, and the final survey collected responses from ten remaining participants. The summarized results of the initial surveys are below (Biosecurity 1 and Partner Farmer Profile as summarized using Google Poll).

SUMMARY_FINAL_Swine Biosecurity Survey 1

FINAL SUMMARY_Partner Farmer Profile

The Partner Farmer Profile survey captured basic information about partner farmer demographics and their farm management practices:

- The range in maximum number of pigs varied from 30 to 650 head, which is considered very small by commercial industry standards. This implies different infectious disease risks and transmission dynamics; therefore, scale-sensitive infectious disease prevention tools and concepts may be necessary for this population.

- 60% of farmers identified their operation as "farrow to finish" which means all age groups are continued on one location. This differs from commercial industry practice which may focus on a single production stage at each facility. These different production systems may be associated with different infectious disease risks and transmission dynamics; therefore, production style- specific infectious disease prevention tools and concepts may be necessary for this population.

- Almost 80% of the farmers fell in the age range of 30 to 49 years and were evenly distributed by years of experience from 0 to 20 years. This was expected to correlate with a more tech savvy and social media friendly group who may also be inclined to learn from one another using these technologies.

- Farmers reported seeking information regarding swine management mainly through internet searches, other farmers, veterinarians, books, and Cooperative Extension/Universities/Experts. 60% reported that they belonged to an industry association. This response indicates several valuable outlets for communicating with the demographic of this report.

- Almost 80% sold piglets and pigs directly from their farm and the same percent report participating in retail sales of pork products directly from their farm. These direct sales represent a potential significant biosecurity concern for these farms; however this is a critical component of many of these farm businesses.

- Only one participating farm was certified organic. Further discussion on this topic indicated that farmers felt that their small scale, transparent production methods were valued by their customers and seen to supersede the value of organic certification.

- Almost 20% of farmers reported that they did not contract with a farm veterinarian. Based on participant feedback gathered during the project this was more commonly due to perceived lack of need or utility rather than lack of opportunity

- All but one responder indicated that they raised other livestock on their farm with the most common types being poultry (chickens, ducks, turkeys) followed by cattle then sheep, goats, llamas. Comingling of livestock species carries increased risk for direct or indirect contamination with infectious disease agents, and is particularly concerning with respect to shared influenza viruses between swine and poultry. This may be one distinguishing and significant feature of small scale swine production systems in the Northeast.

The Swine Biosecurity Survey collected information about responders' operational management, preventative herd health practices and disease transmission risk awareness:

- 60% permitted off-farm visitors access to the swine management areas and of those, 50% report visitors are allowed direct access to the pigs. While this practice is known to be a significant biosecurity risk, agritourism in this region is one of the most common ways to ensure economic viability of small farms.

- While partner farmers report practicing basic biosecurity when visiting other swine operations, such as washing and disinfecting footwear, they did not report requiring that of visitors coming to their farms.

- The majority of responders (85%) offered outdoor swine housing, including pasture and woodlots. For those animals that were not exclusively housed outdoors, the pigs at least had free access to the outdoors. Four responders report seasonal confinement of their hogs with open/natural ventilation. These housing practices exemplify an important difference between these example Northern New England transitional swine herds and confinement raised industry swine. This lack of environmental control in the NNE swine population is a significant consideration for disease prevention and control planning.

- Related to this emphasis on outdoor housing, all partner farmers reported their pigs had potential contact with wildlife like rodents, birds and scavenger species like racoons, skunks and opossum.

- 85% of respondents felt only "Somewhat Confident" or "Not Confident" about being well-protected from contagious disease vs. 15 % feeling "Confident" or "Very Confident".

- The three most common reasons responders cited to explain low levels of biosecurity on their farms were:

- 1. Expensive

- 2. Too Time Consuming

- 3. Don't Know Which Recommendations Are Right for My Farm.

Using the results of these two Pre-Study surveys, the study team designed a 2-hour Swine Biosecurity Training webinar intended to resonate with the reported philosophical and managerial characteristics of the audience. The webinar addressed some of the participants' unique situations and perceptions and described the "how" and "why" of farm biosecurity using familiar or likely scenarios.

Healthy Farms Healthy Agriculture Biosecurity Audit (On Farm Assessment) was used as an additional tool for site specific biosecurity training for study participants. A copy of the completed Healthy Farms Healthy Agriculture (HFHA) farm biosecurity audit and site specific recommendations addendum was returned within 7-10 days of the farm visit. Delivering these recommendations in tandem with the farm's infectious disease surveillance testing report provided a concrete point of reference for the significance of this biosecurity evaluation. In addition to a variety of site-specific observations and recommendations, every participant was uniformly encouraged to (1) assign a site biosecurity coordinator, (2) develop a site map indicating the Perimeter Buffer Area and Line(s) of Separation, and (3) implement or increase signage on site to inform visitors, customers and service providers of the site's biosecurity protocols. To support participant efforts in implementing this last recommendation, the research team produced and distributed custom Farm Biosecurity signage using photos of the pigs in this study. The design of these signs was intended to connect with the farm operators and potential farm guests by featuring heritage breed pigs in familiar environments with simple biosecurity messages.

This on farm evaluation and the Final Biosecurity Survey (See "Post Study" report) revealed two additional areas commonly identified for biosecurity improvement: (1) manure and mortality management and (2) quarantine practices for new or sick animals. Specific recommendations were provided to each farm to assist with maximizing their current infrastructure and resources in these categories.

POST-INTERVENTION SURVEYS

Instead of repeating the exact questions we asked in the preliminary Biosecurity Survey, we designed new survey questions to capture indications of change in knowledge or biosecurity practice, as well any new intentions to implement practices learned about during the project. 10 of the original 14 partner farmers completed the entire project. A modest research participation stipend was provided to all partner farmers that completed the project, which may have positively contributed to the 100% response rate achieved for this final survey. Highlights of the final biosecurity survey results and accompanying analysis are presented below:

Reporting of Biosecurity Practice Post Project Intervention: Which of the following biosecurity practices (17) are in place on your farm? We identified the following 10/17 biosecurity practices that were common for the study group, as determined by 6 or more respondents answering “Yes”:

|

Practice |

Yes, not a new practice |

Yes, a new practice |

No, I don’t do it now |

No, will implement |

|

Keep records when I buy or sell pigs

|

9 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

|

Keep pig herd production records |

9 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

|

Have a herd vaccination protocol |

9 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

|

Quarantine protocol in place for new pigs |

9 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

|

Mortality disposal plan for multiple adult carcasses |

8 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

|

Isolation protocol in place for sick pigs |

8 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

|

No plate food waste allowed to pigs |

7 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

|

Hog feed is secure from insects, rodents, and birds |

7 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Disinfection plan for equipment |

6 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

|

Worker protocol to use clean boots and outerwear |

6 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

The results of this survey question highlighted a few areas of disagreement between self reported practice and that observed by the research team as guided by the HFHA evaluation. For example, while participants understood the need, reason and how to quarantine and isolate new or sick animals, field observations indicated that few sites were able to implement best practices for true animal quarantine. Additionally, most participants believed they had the ability to handle disposal of multiple adult pig carcasses via compost in the event of acute death or disease outbreak. In this case as well the research team found that best practice composting was not being implemented; rather manure piling and carcass burial was the norm.

In response to these observations, the research team developed a 1-page Quarantine Checklist and hosted an in-person learning opportunity featuring a nutrient management specialist from the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry and a composting subject matter expert from the Maine Department of Environmental Protection. This learning opportunity also featured guests from regional farm service support agencies such as NRCS, FSA, and the University of Maine Cooperative Extension.

A lingering biosecurity gap: Do you prohibit mixing of other livestock with pigs?

|

Practice |

Yes, not a new practice |

Yes, a new practice |

No, I don’t do it now |

No, will implement |

|

Prohibit mixing of other livestock with my pigs |

4 |

0 |

6 |

0 |

Most farmers allow mixing of livestock with their pigs, with 6 of 10 farmers claiming this practice. Free range poultry (various species) and pets were most commonly reported and observed while conducting the HFHA survey. This practice remained despite education from the study team delivered through the Biosecurity Webinar, the on-farm biosecurity assessment and written follow up recommendations. This practice may persist due to cultural values, infrastructure limitations, skepticism regarding the risks or other unknown reasons.

Six New Biosecurity Practices: We identified the following recommended biosecurity practices that were or will be newly adopted by study participants. These are areas where we feel the study made headway in learning and behavior changes:

|

Practice |

Yes, not a new practice |

Yes, a new practice |

No, I don’t do it now |

No, will implement |

|

Have a site map of my farm |

|

1 |

|

4 |

|

On-farm signage to inform visitors of protocol |

|

1 |

|

3 |

|

Assigned biosecurity coordinator |

|

2 |

|

2 |

|

Have a herd veterinarian |

|

2 |

|

1 |

|

Visitor protocol that assesses visitor risk |

|

2 |

|

1 |

|

Visitor protocol that limits direct contact with pigs |

|

2 |

|

1 |

Where we noticed the most inroads in terms of change of practice or intention to change a practice from this study were in the categories of (1) protocol for visitors and (2) starting a biosecurity plan with an assigned coordinator and a site map. To further support these preferentially adopted practices, the study team developed a single page Farm Visitors Checklist guidance document, and advertised "Biosecurity Office Hours" with the Maine DACF Livestock Specialist (Carol Delaney) for free biosecurity planning consults.

Additionally, two farmers had reported a new working relationship with a veterinarian and one planned to find one in the next year. This represents a 30% positive change in producer connection to swine veterinary resources, which we hope will support continued herd health and improve the pig health promotion practices of the farmers.

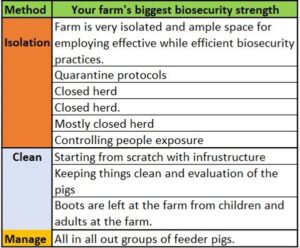

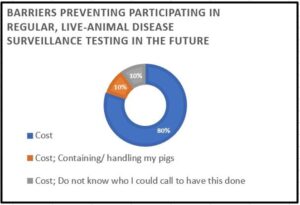

Partner Farmers self assessment: Through multiple biosecurity education components of this project, we hoped to teach participant farmers new biosecurity practices as well as identify what practices they may already have in place, whether or not they were recognized as "biosecurity." The following open-ended survey questions asked participants to identify their farms biosecurity strengths and weaknesses, drawing on their post-project intervention knowledge:

Regarding farm biosecurity strengths, the follow three strategies were commonly described by responders:

- Isolation

- Sanitation

- Management

We also asked participants to reflect upon their farms’ biggest biosecurity weaknesses. 5/10 responders identified farm visitors as their farm's highest biosecurity risk. The second most commonly identified biosecurity risk was herd exposure to wildlife or other livestock in contact with their pigs.

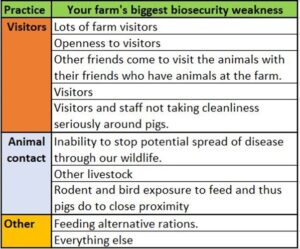

Infectious Disease Surveillance Test Reporting:

The majority of partner farmers indicated that the results of the infectious disease surveillance testing of their herd was in agreement with their assumptions. It's important to note that initial study surveys attempted to gather information about which disease agents the participants felt knowledgeable enough about to design a specific prevention plan for, including many agents that were part of this project's surveillance plan. Most participants did not specifically claim knowledge about these agents, so it's likely their assumptions were based on more general conclusion such as "freedom from disease" vs awareness of their herd's specific infection status relative to control practice needs or vulnerabilities. The value of these surveillance reports is to add specificity to these producer's assumptions about their herd's health status in order to direct their efforts in disease prevention to the most necessary and efficient methods.

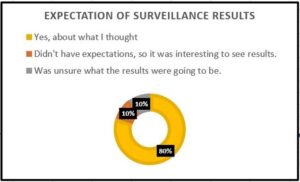

We also assessed whether partner farmers would want to continue this surveillance testing program with their herds as an indication of their valuation of this information. We first assessed if they would participate again in infectious disease surveillance activities if offered again with full external funding, and answer was a resounding 100% “Yes." To test the strength of their resolve and the value they placed on the disease surveillance testing, we then assessed whether partner farmers would again participate in infectious disease surveillance if there was no external funding available, and the response of “Yes” dropped to just 20% and the majority of responders chose “Maybe”. It was encouraging that no farmer chose “no”.

To ascertain the barrier to continuing disease surveillance we assessed: “What barriers may prevent you from participating in regular, live-animal disease surveillance testing on your farm?” The multiple choice answers options included: Cost, Containing/Handling my pigs, Do not like the snare being used on my pigs, Do not want to have other people on my farm, Do not know who I could call to have this done, Takes too much time, Do not think this is valuable, Worry that it would cause unwanted attention to my pigs from regulators, customers, other farmers, etc. or Other. All responders indicated that cost was the major barrier to their initiation of this type of investigation:

Once the cost of such a program is shifted to the farmer, they could not commit to continuation of this annual surveillance. Of note, the actual cost of the diagnostics performed in this study was not shared with study participants. Therefore, this question was answered based on the partner farmers' previous experience contracting with private practice veterinarians or their assumptions about the cost of this service. One possible area for future investigation could aim to elucidate the factors considered by NNE swine farmers in assessing their financial threshold or factors considered when making these decisions about seeking veterinary involvement for herd management versus herd illness or production issues.

Partner Farmer Confidence in Swine Herd Protection was assessed following surveillance testing and delivery of biosecurity education and training:

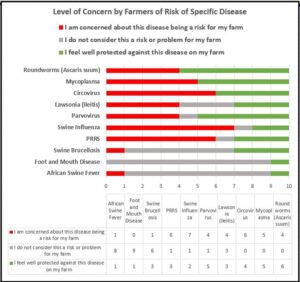

The diseases that appear to be of least concern to the study group are those categorized as Foreign Animal Diseases (FADs): Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD) and African Swine Fever (ASF). While of low concern to the study group, these FADs are of high concern and importance to USDA and State Departments of Agriculture. It's unclear if partner farmers are not concerned about these diseases because they feel well informed and actively protected from these disease introductions or if they are dismissive of this risk. This is an important potential area for further investigation in this population of livestock producers.

Swine Influenza (SIV) (70%) followed by PRRS and Circovirus (both 60%) then Mycoplasma (50%) were the diseases of highest concern to the study population. Circovirus and Mycoplasma were revealed to be common endemic infectious agents in our region, thus it is understandable that participants would rate them highly as a threat to their herd. The high threat rating participants indicated for both SIV and PRRS suggests that participants understood the negative impact of these diseases for their herd and their vulnerability should they be introduced, given this population's lack of innate or vaccinal immunity.

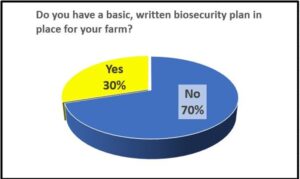

Study participant feedback regarding the project’s influence on their knowledge and behavior was solicited through a series of final questions identifying implementation of major biosecurity recommendations and self-rating of knowledge gained. Only 30% of project participants report that they have developed a written a biosecurity plan for their farm. However, at the inhiation of this project only 1 participant (10%) responded that they had a biosecurity plan. While this improvement is small, this gain indicates some positive impact for this study group and suggest a future focus area for livestock service providers. Identifying opportunities for supporting this sector was one goal for this project, so this result is doubly impactful.

In this final biosecurity survey we also solicited information from study partner farmers about their experience in the project and perceived value of participation. Some participants expressed that they had made significant time or financial investments in herd genetics and were motivated to protect this product and related markets. Additionally, small scale swine production with limited opportunities to capture efficiency is associated with significant costs, so disease prevention and control is necessarily one of the foremost concerns of NNE commercial pig farmers in limiting further challenge to these fragile production systems. In this post-study context, we again asked partner farmers: “How confident are you that your farm is well-protected from contagious disease?”

|

Responses |

Pre |

Post |

|

Not confident |

0 |

0 |

|

Somewhat confident |

9 |

0 |

|

Confident |

1 |

3 |

|

Very confident |

0 |

7 |

100% of responders indicated that they felt confident or very confident about their biosecurity practices' ability to protect their pigs from diseases entering their farms. This shift in confidence confirms that this project's partner farmers benefited from participating in this study. Further, when asked to rate their change in knowledge and understanding of biosecurity practice on NNE swine farms, 90% of participants rated this experience as a learning opportunity: “Based on your participation in all aspects of this study, do you feel your knowledge of infectious disease prevention through biosecurity practices has:”

|

Remained the same |

1 |

|

Increased |

9 |

|

Become less clear |

0 |

|

Other |

0 |

Future partner farmer interest in remaining connected to swine health resources and communicating needs to the study team was assessed though a series of multiple choice and free choice survey questions. The project leaders and partner farmers had developed a level of trust and connection throughout the study period. The research team was diligent in protecting participants' identity and offered unbiased, respectful feedback. Partner farmers shared personal farm information and opened their facility to evaluation by government regulators. To ascertain if the farmers valued this experience enough to continue working on the topic of farm biosecurity with this team, we assessed “Are you interested in continuing to address this topic of infectious disease control and biosecurity practice for pig farms? A tree map presentation of the selected responses is presented below, noting that no responders selected “No, not interested” or “Other."

80% of responders indicated that they would engage in "Individual consultations with a livestock specialist to assist implementation of site-specific biosecurity plan." Though only 30% of this study's partner farmers currently have a written biosecurity plan, 80% of participants report that they value this and wish to complete one with assistance. This supports the conclusion that creating a farm biosecurity plan, even when using a preformulated template and receiving site-specific feedback, remains a significant burden or challenge. This group of responders indicate that the support of a partner in the form of consult from a livestock specialist is needed to assist with completion of this task. Many responders were also interested in Farmer Discussion Groups, facilitated by a swine specialist (7 selection) or by an industry association (6 selections). Responders also favored al carte educational offerings by state organizations (7 selections). There was also reported strong interest in regular consultations with private practice veterinarians (7 selections).

Objective 2: Infectious Disease Surveillance Study

Each partner farmer received the results of their swine herd's individual infectious disease investigation. The value of these disease reports to the individual farmer was to provide a point of reference for preventative health planning for their herd (vaccination and biosecurity practice), to use as an indication of their herd's current vulnerability to select infectious diseases and to serve as a basis for quantifying the level of success of their farm's current biosecurity practices. This amount of herd health surveillance data is rarely available to swine managers in NNE primarily due to the high cost of obtaining this data. Partner farmers appreciated the depth of this information about their herds and expressed interest in continuing to monitor select diseases from the overall surveillance plan that were identified as endemic in their herds.

The collective results were summarized and shared with the project partner farmers, regional swine producers and service providers including Maine and New Hampshire large animal veterinarians and Cooperative Extension staff. This information was shared at multiple events: (1) Large Animal Veterinarian Continuing Education (virtual) hosted by DACF (March 2021), (2) Maine Swine Producer's Association Annual Meeting (May 2022) and (3) Swine Health Education Seminar (October 2022). The collective results are valuable to the regional swine industry and their service providers as evidence of what infectious diseases to expect among the local swine population. This knowledge will help to direct service providers in their efforts to support this industry, resulting in targeted disease prevention guidance and awareness of the industry's specific vulnerabilities and resources for combatting these challenges.

Summarized results and analysis from the infectious disease surveillance phase of this project are below:

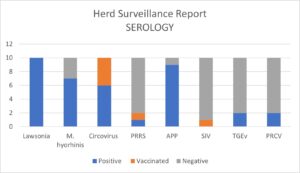

Collective Swine Herd Serological Surveillance results document multiple regionally significant trends.

All herds tested positive for antibodies to circovirus, indicating this is a common agent in NNE swine herds. Of this sample group, 60% of herds testing antibody positive were due to natural exposure to this virus; 40% were vaccine induced or possibly both. Many herds were vaccinated against M.hyopneumonia, so serological surveillance for M. hyorhinis was selected instead. 70% of the sample group tested positive for exposure to this mycoplasma species, none of which was expected to be vaccine induced antibody.

Exposure to Lawsonia and Actinobacillus pleuropneumonia was nearly universal, with few herds reporting recent outbreaks of disease, but several herds reporting subclinical levels of signs compatible with chronic herd level disease (diarrhea, stunting, sudden death).

In contrast to surveillance reports from commercial swine in the mid-west, Northern New England transitional swine were significantly less likely to demonstrate exposure to Swine Influenza Virus and PRRSv. One herd in this study group testing PRRSv antibody positive was a single antibody positive in an imported pig, with no additional positives in that group suggesting prior exposure with no onward transmission of virus. The second herd positive was a group of imported PRRS/SIV vaccinated gilts from a commercial producer in the Midwest, and this antibody detection was likely vaccine induced based on available origin-herd history.

Only two herds in the study group tested positive for exposure to two different coronaviruses of swine: one that causes primarily intestinal illness (TGEV) and the other causing primarily mild respiratory disease (PRCV). One of these herds was assembled from swine originating in the Midwest. The other herd was a low biosecurity herd with frequent movements of swine into and out of the herd from various suppliers.

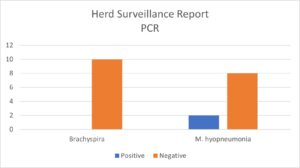

Collective Swine Herd Molecular Surveillance was less useful due to low detection levels of infectious agents in clinically normal animals. None of the animals included in this study group tested positive for brachyspira, the agent causing "swine dysentery" and only one animal was detected carrying mycoplasma hyopneumonia, the agent causing "enzootic pneumonia" of swine.

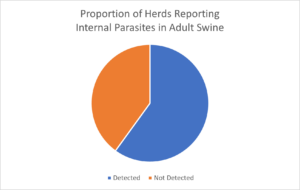

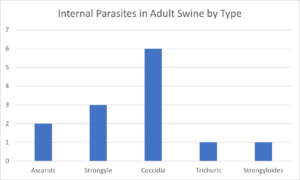

Collective Swine Herd Internal Parasite Surveillance results indicate that the majority of herds in this study group are affected by some type(s) of internal parasitism. This is notable because the representative fecal sample collected from each herd was from a mature animal group, indicating a stable herd level infection rather than young animals colonized due to immature immunity. The predominant internal parasite recorded was various coccidia species from asymptomatic adult swine. This result supports the importance of pre-farrowing treatment of sows and gilts and environmental sanitation practices in the farrowing house and young pig environments. Most participants expressed an interest in receiving recommendations for swine deworming practice, which is necessary for swine health and productivity as well as human public health. Importantly, most swine producers in this study are not able to handle individual animals easily, making oral administration of anthelminthic the only practical delivery route. Therefore, in this population we learn that maximizing management factors such as stocking density, pasture rotation, sanitation and strategic administration of appropriate injectable deworming agents, plays a critically important role in internal parasite control in the NNE swine industry.

Our project successfully documented demographic information, farm management practices and changes in biosecurity knowledge in the Northern New England Swine industry through a series of online surveys. We also documented conformity of self reported biosecurity practice to that observed by the research team through use of a comprehensive on-site farm biosecurity evaluation. Lastly, we documented endemic infectious disease prevalence information for a representative group of NNE’s swine population, information that is rarely sought and shared regionally.

Multiple educational products resulted from this project, including a 2 hour virtual Swine Biosecurity Training webinar, two swine biosecurity checklists targeting areas of biosecurity opportunity identified through this project and several custom NNE swine farm biosecurity signs. The research team was able to repurpose funding resources during the project to respond to the management trends identified through these research surveys. This resulted in two additional opportunities to expand biosecurity training and support to swine producers in Maine and New Hampshire, including those external to the study group. These education events included distribution of biosecurity and compost management supplies, which significantly impacted farmer biosecurity management behavior as determined by follow up survey of audience members. This impact was especially strong in the context of an education event which described how and why to use these supplies. Survey responses from producers who attended an education event and accepted biosecurity supplies captured the fact that this distribution event eliminated "supply" as a barrier to use, and attendees reported that they did use the materials distributed as described in the seminar. Examples of biosecurity supplies provided at these two events included: a foot bath tub, visitor policy signage, compost thermometer for proper disposal management and single use boot/shoe covers. Supplies distributed to Agricultural Service providers in attendance at these events were later distributed through them to additional farmers that had not attended the specific training event.

This study combined farmer training, context building through demonstration and material support to effect change in biosecurity management practices on NNE swine farms. The products of this study, including the regional swine herd surveillance report and recorded biosecurity trainings, should provide an enduring and more widely distributed support to this industry.

Education & Outreach Activities and Participation Summary

Participation Summary:

Webinar: A 2 hour Swine Health and Biosecurity Webinar was delivered on January 20th 2021 to 14 partner farmers enrolled in the study. Their participation in this instructional presentation was intended to deliver introductory level biosecurity training, familiarize them with the concept of site-specific biosecurity planning, and prepare participants for the on-site biosecurity evaluation phase of the project. Feedback solicited from the 10 partner farmers who completed the entire project suggests that the webinar material was perceived to be relevant and understandable. A PDF of the webinar content is available: JAN20_SARE Swine Health Webinar. A recording of the project's Northeast SARE Swine Health and Biosecurity Webinar is here.

Veterinary Outreach: The Animal Health Program within the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry offers RACE approved veterinary continuing education credits. In March of 2021 Dr. Carolyn Hurwitz presented to this audience (23 attendees) on the preliminary stages of this study, including initial results of industry demography, reported biosecurity management and opportunities for access to the final study report and conclusions. This presentation was intended to characterize the region’s swine clientele for veterinarians that already do or will consider seeing swine in their scope of practice. This event was also used as an opportunity to advertise that swine herd surveillance data would be available at the conclusion of this project. It was anticipated that the herd surveillance data would provide focused information about locally prevalent infectious disease in this population of swine, which may impact considerations such as vaccination recommendations, differential diagnosis and biosecurity management recommendations.

On-farm demonstration: The study group contributed a short, hands-on training focused on farm biosecurity practices for visitors at an event hosted by the Maine Organic Farmer and Gardeners Association (MOFGA). This MOFGA sponsored workshop was hosted by one of the study’s partner farms in August 2022. We successfully captured this opportunity to expand the reach of our biosecurity education and support one of the study’s participant farms implementing new, elevated biosecurity practices for agritourism. The demonstration included a hands-on training for all participants to properly select and prepare a disinfectant and apply it to their farm boots before continuing into the livestock areas. We facilitated biosecurity-focused record keeping for this event by asking attendees to sign in and indicate if they had been in contact with other livestock in the previous 72 hours. Attendees of the MOFGA sponsored event reported that the additional biosecurity training was useful. (13 farmers/interns, 1 ag service providers)

In-person educational events: The study investigators presented a summary of the project’s surveys and disease surveillance results at the annual Maine Pork Producers Association meeting on May 12, 2022. At this meeting, we shared two new resources for swine producers that had been developed in response to partner farmer needs: the quarantine checklist and the farm visitation policy checklist. We also shared copies of custom- designed farm visitor-policy signage featuring images of common heritage swine breed in the region. These signs include a prompt for the farm owner to indicate contact information for their site biosecurity coordinator and discourage entry without permission. At the conclusion of the event, the research team shared additional biosecurity supplies with attendees for use on their farms to promote biosecurity practice as discussed in the presentation. (13 farmers, 2 ag. service providers)

A second, more comprehensive summary of the project results was delivered on October 28, 2022 at a day-long seminar organized by the study group. The intent of this seminar was to share the project conclusions with participants, regional Ag service providers and other swine producers in the region who had not yet been reached by the study organizers. The project summary was supported by additional educational content based on areas of need as identified through the project surveys and on-farm observations. The unifying principle of the days’ presentations was “nutrient management:” from manure and mortality management and planning, to food waste and using swine to repurpose those nutrients.

Several regional experts were invited to this seminar to present on these topics: (1) Dr. Mark King, Maine DEP Composting SME, presented on proper construction and maintenance of a farm compost pile for manure and mortality management. This presentation also introduced the concept of mortality planning for catastrophic events. (2) Mark Hedrich, Nutrient Management Specialist with the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry, offered subject matter expertise to attendees on the topics of carbon source selection and evaluation, and compost pile monitoring using the compost thermometers provided to attendees. (3) Luis Aponte, NRCS District Conservationist for York and Cumberland Counties presented on the topic of USDA funding opportunities for farmers planning to invest in nutrient management infrastructure at their operations. (3) Laura Thiboutot, Director of USDA FSA office, explained the funding opportunities and farm support programs available through their office and introduced attendees to tips for success in the application process. (5) Dr. Colt Knight presented on Alternative Feeds for Swine, educating the audience on basic swine nutrition and an analysis of multiple examples of alternative types of feed and their impact on the overall quality of the resulting pork. Lastly, (6) Brittany Hemond, president of the Maine Pork Producers Association, explained the benefits of membership in this organization and encouraged farmers to join and network with other swine producers in the region. Attendees to this event were supplied with biosecurity tools for their farm such as Virkon, Bleach, hand sanitizer, boot covers, rubber over-boots, tubs for scrubbing footwear and boot brushes. Attendees were also offered a 36 inch ReoTher compost thermometer to support their implementation of the techniques described during the carcass composting presentation. Descriptive feedback regarding audience members’ use of these supplies is summarized in “Learning Outcomes.” Total attendance was 22 audience members and 2 research team members. This included 15 farmers, 1 farmer/Ag Educator, and 6 Ag service providers.

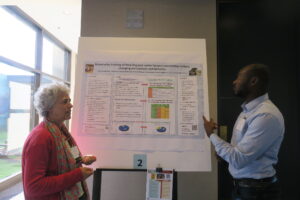

Poster Presentation: Carol Delaney, Maine DACF Livestock Specialist and study co-lead, presented a preliminary research poster at the International Workshop for Agritourism in Burlington, Vermont on August 30-September 1, 2022. This poster focused on the behavior changes measured through this project based on data collected from the ten farms that finished the entire study. This presentation highlighted the increased perception of risk posed by farm visitors as reported by study participants. In-person attendees numbered approximately 350 people with an additional 150 people online. This international conference attracted attendees from about 50 countries. At the poster session, Carol Delaney connected with a graduate student from the University of Vermont who was very interested in this work due to their recent polling of livestock producers across the country.

Sharing: Maine Large Animal Veterinarians, regional State Animal Health Officials, regional Cooperative Extension Livestock Service Providers and all participants and attendees to this project's educational events will be notified of the link to the final report.

Learning Outcomes

In the preliminary survey, 70-80% of responders shared that they allowed visitors inside their swine management areas with some even permitting direct contact with their livestock. After participating in the study, 50 % of the farmers reported that they identified having visitors on their farms as their operation’s greatest biosecurity weakness. This pre and post intervention difference in survey response represents a beneficial change in perception of risk. Additionally, at the beginning of the study, "cost" was identified as the biggest barrier to implementing biosecurity practices. In response, participants were provided with the supplies they needed, free of charge. They were also educated about the true (low) cost of basic biosecurity supplies as well as the cost-free biosecurity concepts such as: using visitor signage, having a protocol to assess visitor risk and implementing a protocol to limit visitor contact with pigs. In final surveys, 30-40 % of responders indicated that they have now implemented or are planning to implement these practices.

Project Outcomes

Participant Survey outcomes:

- Participating farmers with written biosecurity plans went from 1 to 3 (out of 10 total)

- 40 % have or plan to add visitor signage

- 30% have or plan to use risk assessment tools to assess visitor risk

- 30% have or plan to change to limit visitor access to pigs

Outreach events outcomes:

The result of this project’s various outreach events include: provision of basic biosecurity supplies and training to attendees, increased connection among regional swine producers and between producers and service providers.

The final outreach event was the most comprehensive and attracted the largest audience. Attendees received an email survey to capture information about if and how they utilized the tools they were provided at these seminars. We received 18/30 responses, summarized below. The full results of the survey are found here: Swine Biosecurity Survey post training May 2022.2

The most popular items attendees brought home were:

- Compost thermometer

- Boot or shoe covers

- Plastic tubs with brushes

- Visitor signage

When asked how their taking home free biosecurity supplies affected their biosecurity management practices, almost 40% of the responders indicated that this improved their overall farm biosecurity management with 22% indicating this allowed them to add a new biosecurity protocol.

| How farmer biosecurity management was affected by receiving supplemental biosecurity supplies | # Responses | % Responses |

| Improved my biosecurity management | 7 | 39% |

| Allowed me to continue the same biosecurity management | 5 | 28% |

| Added a new biosecurity measure or protocol to my management | 4 | 22% |

| Other | 2 | 11% |

| Grand Total | 18 | 100% |

Participants that received biosecurity supplies form this project were asked to share how they used the biosecurity supplies. This was an open ended question and the following feedback was received:

"I have distributed all the signage that I took from the event. This has gone to farmers directly and feed stores for further distribution. The signage was well received, and farmers immediately saw the benefit from hanging signs on the farm."

"We've used the bleach to disinfect the trailer after trips to the processor. We've used the hand soap for washing hands when working with the animals."

"The boot covers I use when entering the stalls of all my animals. The hand sanitizer is applied to my hands randomly when preforming my chores. The visitor signs are posted at the entrance of my property. The rubber boots I have not worn as of this posting."

"Sanitization of hands. Plastic boots covers for off sight workers/visitors. Hung signs outside of barn, tested compost thermometer..."

"We don't allow visitors on the farm so we end up using this material to scrub between barns and have used with the few people allowed on the farm. We plan to trial composting this coming year so the thermometer should come in handy with the learning curve."

"Plastic tub for scrubbing in and out, excited to use the thermometer."

"I have put up signs and they have effectively kept unwanted visitors out or at least had visitors I was not expecting call me and ask for permission to access the barns. I have boot covers now for visitors on the farm. I also set up my boot tubs and have started to wash my boots consistently. I have played with the compost thermometer some and am keeping an eye on the temp of our manure pit!"

"Boot washing so far, plan to use compost thermometer."

"Better knowledge is helping us keep our animals safe. Compost thermometer is giving us much better info of how our composting is working or not working."

When asked about which biosecurity supplies they had not yet used, 85% of respondents chose the response "Waiting for the appropriate time and intend to use them." Responders provided the following additional detail:

'Useful. Boot covers are great for on site visitors. Quick and efficient! Quick sanitization as well. In house biosecurity could increase with disinfect however we have prioritized sets of boots just for our farm. Our compost could improve next year as well with multiple bays."

"Yes it is useful for farms already concerned with environmental diseases we all face now with wild animals and other diseases spreading so much faster these days. I do believe we all need to continue to educate the public as to why biosecurity is so important and why the public can be just as devastating to farmers even if they just stop by cause they think the animal is so cute just have to pet it. Educate the public is always going to be an agenda for every farmer every day."

"I was very grateful for the supplies and it has helped my operation! Thank you for all your time and effort in this project!!"

"The distribution of the items is very helpful. It sort of puts the use of the biosecurity items right, front and center. Many know these items should be utilized however don't go the extra step to acquire the items. So this helps them get started and then once in the habit of using them often people will then continue using them and purchase them after they run out."

Based on this feedback it appears that the biosecurity supply distribution was a successful and impactful component of this project and the presentation events.

An unexpected result from this project was the inspiration and justification to expand the role of the DACF Livestock Specialist into biosecurity programming and farm biosecurity consulting. Carol Delaney has now adopted this topic as a focus area for her programing with DACF, assisting any livestock farmers in Maine to develop and write down their farm biosecurity plans. This project underscored the importance of continuing to support producers past the education phase through implementation by offering coaching and accountability for developing a written, site specific biosecurity plan. Resources developed through this project form the basis of a new “biosecurity binder” resource that will be expanded as this programming grows and as participating farmers contribute their own materials for their customized farm biosecurity plan.

We believe that the results of this study are valuable as a limited point of reference for common swine management practices, attitudes about farm biosecurity and overall swine herd health in this region. Limitations of this data set include the small sample size and the lack of durability of these data. Trends in farm management practices and swine herd health status are likely to drift over time and these data should be interpreted with that in mind. A larger sample size in terms of both partner farmers and number of swine sampled was anticipated. The study group encountered some logistical challenges to recruiting participation, which may be improved now that there is greater partnership between DACF and this livestock sector. Lack of access to adequate swine handling facilities is likely to continue to pose a challenge to recruitment of additional swine for live animal testing.

Due to the need to maintain confidentiality of study participants, it was challenging for the study team or organize this group of farmers for the purpose of continuing education and networking. One goal of the study was to provide information to Agricultural Service providers in the region, and ideally UMaine Extension and UNH Extension will continue with this contact list and offer more programming that captures the interest of this group. The involvement of the Maine Pork Producers Association was a highlight of this project's outreach and was intended to facilitate enduing engagement with this industry group and recruitment of new commercial swine producers in the region.