Project Overview

Commodities

- Agronomic: barley, oats, wheat

- Fruits: apples, berries (other)

Practices

- Crop Production: malting

- Education and Training: extension, farmer to farmer, networking

Summary:

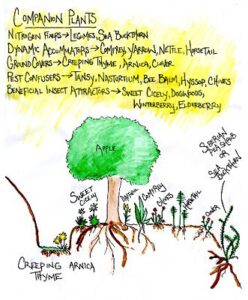

An example of planting around a fruit tree. We used this model

An example of planting around a fruit tree. We used this model

as well as mint plants and basil.

This is an idea we used for planting around fruit trees.

The French and Germans believe in working with nature and the natural deterrents. Many plants repel insects that can cause disease in fruit trees and shrubs, so by planting together this insect-repellent vegetation, you have better potential for reducing disease. The method we used is to start incorporating more insect-repelling plants, which I never thought about using before. An immigrant farmer on our farm is helping me to develop this farming method.

Adjuncts (added to the beer mash) are used in craft beer to enhance flavor, mouth feel, aroma and clarity. Adjuncts have virtually endless uses and can be locally grown such as grain that can be flaked or malted, rhubarb, apples or herbs. The 500+ breweries in Minnesota require a variety of options for adjuncts. With this grant, we will identify which adjuncts are in local demand and move forward to create a collaboration of learning and base connections between breweries and local farmers. Most breweries lack business relationships with the area farmers and order from big malting houses, which takes a huge cut of the profits with the farmers receiving less share. An adjunct added to one singular batch of beer (breweries can have 12 batches brewing) might require 400 pounds of fruit or malted grains. For small farms and diverse farmers, it is a great economic opportunity to sell to a brewery. This grant helps add value to farm products, creates more connections to the land and environment (such as fruit trees and shrubs providing more pollinator habitats, or grains such as oats providing better crop rotation), along with a stronger rural economy.

"Before this grant I never really thought about selling my fruit to a brewery. It has always been a problem when everything is ripening fast and you have to find market share. I think going forward it will fit perfectly to pick everything and drop off at a brewery. It was such beautiful fruit last year before this grant and most of it ripened quickly and I had no market share so the fruit went to waste," said Michele Trangsrud, a North Dakota farmer.

Project objectives:

Identify quantity and quality of grains and fruits to provide in a beer mash followed by documentation of these varieties. The grains for hard red spring wheat that work particularly well are Linkert, Glenn, and Washburn. For flaking, the moisture content of the wheat needs to be above 12%, but this can cause issues for the farmer when it comes to long-term storage of the grain. Usually, a farmer would want 13% moisture of grain, at the highest, for storage in the grain bin, because it can mold especially at high temperatures in summer. However, if the moisture is too low for flaking (under 11%) the wheat would shatter and crush into mush during flaking or look like flour, thus creating a mess for the brewery. Heat, air and moisture are the enemies of whole grains, so a moisture-tester for on-farm use is an absolute must for flaking any wheat to be used as an adjunct.

Provide a stable method of keeping the grains and fruits (freezing, drying or juicing). The fruits need a strong coordination of delivery between farmer and brewery. Mid-sized craft breweries need over 300 pounds at one time. So for picking, cleaning and transportation, there has to be clear communication of time frames, delivery and coordinated processes. We found using fresh was the best, but only if cooling of the fruit, picking and transportation could be done early in the morning. Also, storing fruit in coolers in air conditioned cars was also very important. Most of the more creative artisan breweries prefer fresh fruit while others prefer the fruit to be heated and packaged into a slurry (much like pie filling) for longer storage. Fifty percent of all breweries work with companies from Oregon, which makes fruit from the West Coast our biggest competition. The Oregon fruit comes in foil pouches, which are added directly to the mash toward the end of brewing. One way to make headway in adding local fruits to beer-making is to be able to offer flavors and varieties that are not available from West Coast suppliers. Once the fruit is ripe, there is a short window for the fruit to be picked, cleaned and stored – all during the hottest months of the summer – but it may not fit into the brewers' schedule. Fruit can quickly rot, a storm can knock fruit off the tree or shrub, or birds can quickly eat all of the production.

Marketing of local fruit almost has to take a year in advance, due to the trial and error required on the brewer's part of finding the perfect flavor combination between strong-flavored fruits and bitter hops. Due to the challenges of finding that perfect flavor and marketing setbacks, it is imperative to provide samples a year in advance for experimental purposes to the brewer.

Communicating your quality and quantity projection is another critical aspect to ensure success. Dried fruit is not preferred for fresh local fruits as it adds extra steps of rehydrating. It may be something brewers in the future request, but currently the greatest appeal of local fruit is presenting an opportunity for the brewer to see and smell the the fresh product, get creative as they think of fun ways to incorporate it and be able to market to customers that a local farmer was involved in the process. These positive and emotional experiences all add to the "craft."

Evaluate the taste and consumer acceptance of what sells and what each brewery prefers. This aspect was much more dependent on the subjective palate of the breweries' head brewers. While some may like tart cherries, others may not want that flavor at all. Lead tasters in breweries are very exact and any change of staff also means a change in preference. From everything we have researched, we have found that the fruitier and sweeter flavors are currently preferred by most consumers as opposed to the classic bitterness of grandpa beers. As Corey, head brewer at Junkyard, says: “In the past few years we have seen more buying of fruity, even sour beers with fruit in it. The young generation that is in their mid-20s prefers flavors I would not even of imagined or brewed in my 20s. We have adjusted that quickly and it seems to change going forward.” Another variable that native fruits can add to the brew is color. Once fruit beers are brewed, they exhibit the color of their added fruit, especially in light-colored wheat beers. Fruit can also add a pleasing reddish cast to darker beers, such as stouts and porters. Few fruit beers fall in between these color extremes. Varying health benefits of adding fruit components are just being discovered too, which tends to take away some guilt of having an alcoholic beverage.

The optimal parameters for fruit creates HUGE amount of work yet to do. Some wanted juice, some wanted to juice the fruit themselves. Some use fruit just to strain beer through it while some brew with it. For digging deeper, we texted an assortment of brewers and asked questions, such as:

What fruits would you use if locally sourced?

What quantities would you need for even a test batch?

For organic fruits, the most often stated preferences were for:

- Cherries

- Peaches

- Apricots

- Strawberries

- Blueberries

Share info with other producers and breweries. Because the shrubs and trees do not bear fruit until they have matured, it takes coordination of many farmers together for risk management. One field may bear a lot one year and the other nothing at all. Spring pollination and temperatures dictate what will be available. Best practice is to involve multiple farms and support coordination between those farmers to allow for drop-off and pick-up times for crops. Honeyberries, tart cherries, aronia berries, and apples, for example, show promise for beer making. The best method we found is to enlist friends and family to pick two pounds. They keep one pound and the other pound goes to the farmer. Given the opportunity, getting pre-orders from the brewery is yet another option. Another idea would be a fun "will pick for free beer" promotion: In exchange for picking the berries, the pickers would be able to trade their harvest for gift certificates to the brewery, thus providing a sense of ownership and participation in the process. This would be an especially fun activity during times of COVID-19 because it gives an excuse to be outdoors and enjoy nature all while getting a discount off of a normally expensive alcoholic beverage.

If possible, purchase shrubs and trees locally from your county offices. Shrubs and trees can be expensive, so we bought from Clay County Water and Soil Conservation Office. Every county has an office like this, usually located by the USDA Farm Service Agency. The Conservation office also can be invaluable in helping you determine how the soil in your area matches up with the variety and species of fruit you would like to purchase. In Minnesota alone, soils can shift from heavy, packed clay to sandy soil within a 20-mile drive. (Blackcap raspberries, for instance, do well in clay soils, but not so with other raspberry varieties.) You can also request fruit trees such as pears to purchase from the Water and Soil Conservation Agency, but you usually have to buy a complete bundle of them (30 trees). Then again, at the extremely affordable $2 to $3 per bareroot, it is worth it to order a bundle!

Evaluate the sizes of grains and fruit used by the breweries (thickness or thinness of grain flakes, size of fruit pieces, or whether they prefer to use a slurry).

Meticulously test and track data, setting standards for moisture, protein and fungus. Pay close attention to the Brix scale to measure fruit sugars. The most convenient way to provide for a brewery is to have them give you the exact detail of flake size and you treat this information like it is another ingredient. If there is no fungus and no marks, that means you have a prime fruit. Brewmasters and staff are savvy with taste. There was a time when I switched wheat varieties to see if they could tell the difference and within 10 minutes of dropping off I received a phone call asking why it tasted a bit different.

Evaluate pollinator habitat created. The pollinator habitat is planted and has emerged. For obvious reasons, it is beneficial to have this habitat in tree areas. Farmers can also invite other beekeepers, like we do, to maintain the habitat for the bees. We've found hosting honeybees also keeps native bees working a little harder to compete with the honeybees. This is a win-win. The best pollinator seed is one that you can source regionally to make sure the planted seeds grow, can handle harsh winters and are the right choice for the growing zone. I found pollinator seeds at Agassiz Seed in West Fargo, N.D., and was able to buy in bulk (cp-42 about 28$ a pound.) If using NRCS programs such as EQUIP for developing pollinator habitat make sure that mixture is approved by NRCS before buying.