2017 Annual Report for FW16-035

A Comparative Study of Shading Systems to Control the Beet Leafhopper and Reduce Beet Curly Top Virus in Heirloom Tomato Fields

Summary

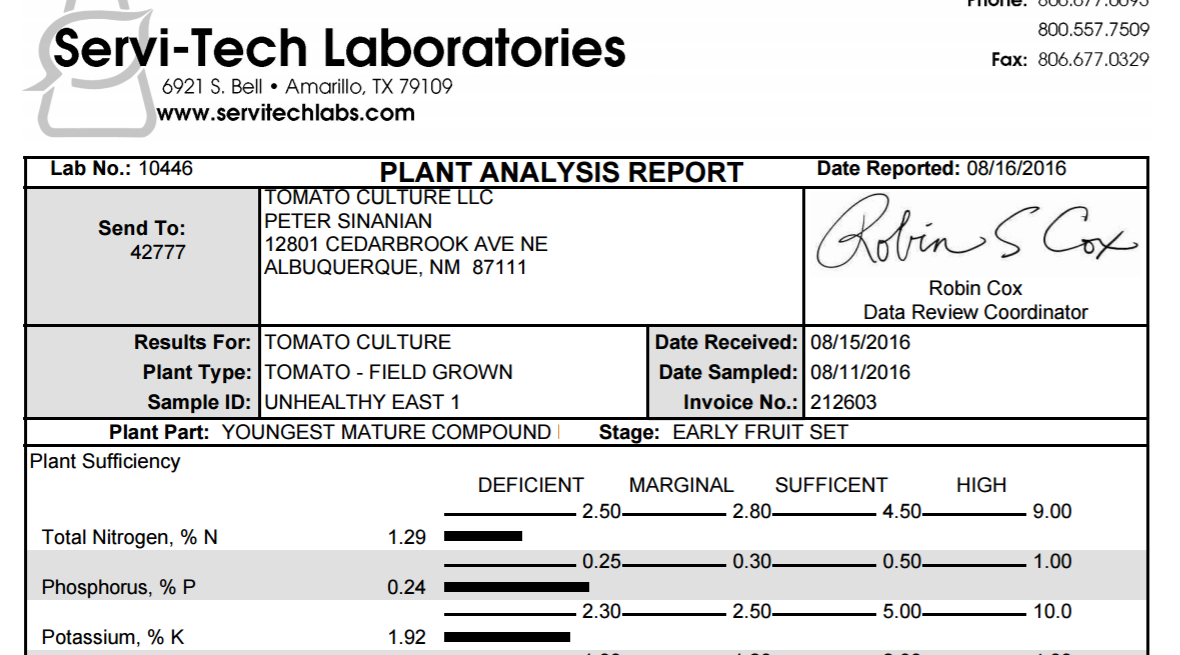

This report comprises our first-year analysis of curly top virus (“curly top”) and its impact on plant outcomes among TomatoCulture heirloom tomatoes for the 2016 season. The farm is in Albuquerque’s North Rio Grande Valley. Curly top is transmitted by the beet leafhopper, the only known vector for this disease. We planted forty-three different varieties of tomatoes (one hybrid, the rest heirlooms) into one of three zones, each divided into three different fields with different growing conditions: Either shaded with shade cloth, in open sun, or interplanted with sunflowers for a dappled shade effect (Figure 1). We analyzed rates of curly top infection among the plants by field and condition, testing the hypothesis that shaded plants would have a decreased incidence of curly top due to the beet leafhoppers’ preference for feeding in bright sunlight. A subset of this hypothesis was to test if interplanting with sunflowers provides the same or better results than shade cloth in terms of deterring beet leafhopper feeding and reducing curly top disease. We also analyzed whether the shaded plants would be healthier overall and produce more fruit.

Figure 1 – Three Zones With Three Growing Conditions Each

The statistical results of our curly top analysis in year one seem to show that the zone in which the plants were located was a more significant factor in disease outcome than the amount of shade received. The number of plants suffering from curly top virus was significantly higher (p<0.05 ) in the easternmost zone (Zone 1). It is important to note that the shaded section in this zone had the lowest loss from curly top of the three sections in that zone. The shaded section in the zone with the next highest overall loss from curly top (Zone 2) also had the lowest loss from the disaese. Oddly, the zone with the least overall losses from curly top (Zone 3) had the highest loss from the disease in the shaded section (3-3) – in fact, Section 3-3 had the highest curly top loss of any of the 9 sections. The sunflower sections performed the worst in Zones 1 and 2, and yet performed the best in Zone 3. In summary, we did not see consistency across the board in outcome by specific growing condition. As of year one, we note some correlation between shading and less curly top burden on our plants. However, we did not see strong evidence that sunflowers and shade cloth are comparable in terms of tomato plant protection.

Interestingly, per plant yields were highest among our shaded sections in Zones 2 and 3. The shaded section in Zone 1 had the second highest yield per plant. These results suggest that over the entirety of the season, the shading supports healthier plants overall. However, the one overriding factor could be soil fertility. We expand on this confounder below.

Objectives/Performance Targets

The following points summarize the outcomes of our year-one research by zone and condition (Figure 3):

- The highest overall loss from curly top was in Zone 2-Section 2 (2-2) at 26%. These four rows were interplanted with sunflowers. The second highest loss from curly top was Section 1-1 at 24%, also a sunflower section. Clearly the sunflowers in these two sections did not provide the needed shade to prevent beet leafhopper feeding. But the lowest overall loss from curly top at 2% was in Section 3-1, also a sunflower section.

- Zones 1 and 2 had the lowest losses from curly top in the shaded sections; 1-3 and 2-3 at 14% and 12%, respectively. However, the shaded section in Zone 3 (3-3) had the highest losses from curly top at 19%. These outcomes suggest that we are on the right track but need to repeat the study and minimize the confounding factors to get better data.

- Zone 3 had the lowest overall loss from curly top at 11%, compared with losses of 13% in Zone 2 and 18% in Zone 1. Zone 3 also had the most fertile soil and the highest overall yield per plant.

- The highest yield per plant came from Section 3-3, a shaded section. This section averaged over 24 pounds per plant, which is very good for heirloom varieties. This section also happened to have had highest soil fertility, confirmed by laboratory testing. The high yields are likely due to the soil as well as the tomato varieties represented in this section. Of all the sections, this one had the second highest number of mature healthy plants at the end of the season. The only section with more healthy plants was also a shaded section, however the yields in that section were less – probably due to poorer soil. Further supporting the importance of soil fertility, the section with the second highest yield per plant was Section 3-2 (directly adjacent to 3-3). This section had no shade. Clearly the fertility was also strong in this section. In fact, Zone 3 as a whole had over 4 times the yield of the other two zones.

- Because we planted each row with a single variety, it is possible that some outcomes may have been influenced by the genetics of each individual strain, rather than the conditions in which they were grown. Although it is true that genetics play a role in plant success, we suspect that field conditions (namely fertility) trumped plant genetics in terms of growing success. In year two, we will include some plants of each variety in all three growing sections to minimize the impact of this potential confounder.

Figure 3 – Summary of Results

Accomplishments/Milestones

It is important to note that there were several confounding factors and farming challenges in 2016 that significantly influenced our results and likely led to the inconsistencies we observed in our results. In year two, we will attempt to eliminate confounders and challenges by making some adjustments to our growing methodologies.

The 2016 farming season served up several confounding challenges that undermined the quality of our data and analysis, preventing us from truly testing our hypotheses. Further study is required before we can draw any conclusions. We experienced the following issues in year one:

- Early onset of higher than average heat, which severely stressed or killed many of our transplants. It was one of the warmest and driest years on record in Albuquerque, with the temperature topping 100˚F in May. The temperatures rose above normal early and often during the most vulnerable time for our tomato plants. The latter part of May, when the plants are becoming established, saw a warm-up that carried over to a June that was 4˚F hotter than average and a July that was 3˚F degrees above the norm. It was a relentlessly hot summer. The early and sustained heat killed many of our tomato transplants under the row covers before they could get established.

- Because of the heat, we had to replant many plants that did not make it through the initial transplanting period. This setback further delayed plant establishment to June, a time of greatest pressure from heat stress and beet leafhopper feeding. The heat also required us to remove our row covers prematurely, exposing the stressed, juvenile plants to leafhopper feeding.

- We put in the sunflower transplants too late and they were too small. They did not grow large enough in time to provide the shade needed by the tomatoes.

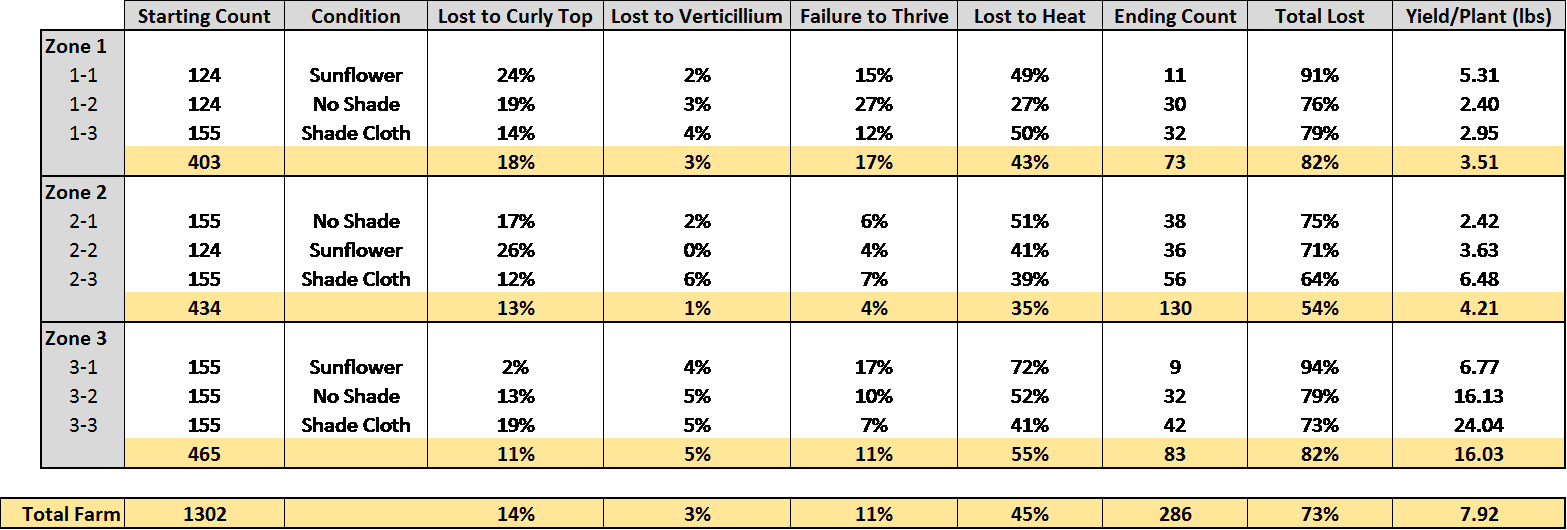

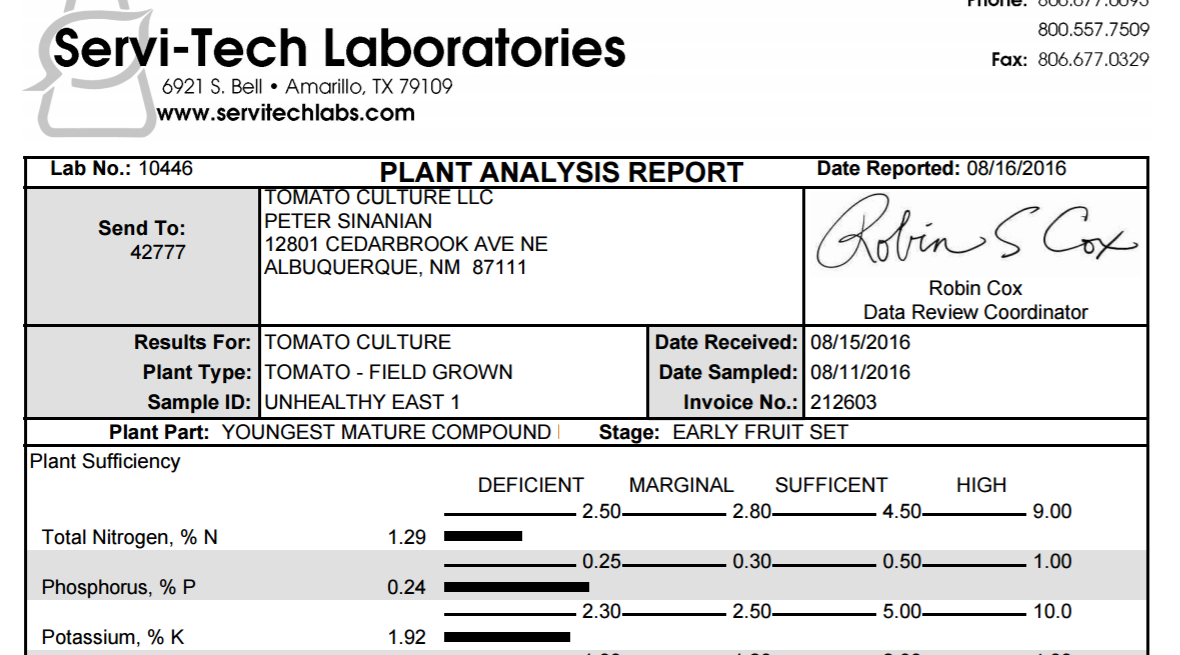

- We experienced uneven soil fertility, likely due to the uneven spreading of horse manure during the prior winter. This mistake created random pockets of high fertility and other areas with below marginal fertility. We confirmed this problem in August through a plant tissue analysis. Lab results (Figure 2) showed that sections with visually healthy and thriving plants had higher than adequate levels of primary nutrients (N, P, K), whereas the sections with visually unhealthy plants were severely lacking in these critical nutrients. Plant health seemed to be more directly correlated with fertility rather than field condition.

- Additional factors that complicated our analysis were the unexpected presence of verticillium wilt and rhizoctonia (fungal root rot), which killed a significant number of plants and made curly top identification more difficult. Many plants failed to thrive after transplanting due to rhizoctonia.

Figure 2 – Plant Tissue Analysis Lab Results

Impacts and Contributions/Outcomes

We will address these confounding factors in year two to the best of our ability by making the following adjustments:

- We will increase the size of our transplants – both tomatoes and sunflowers – to boost survival rates. A larger root ball and thicker stems will help the plants endure the difficult springtime conditions we experience here in the high desert and get the plants off to a faster, stronger start.

- We will plant earlier. Putting plants in the ground while the temperatures are still moderate and protecting the plants from nighttime lows with row covers will ensure the plants get off to a stronger start with minimal leafhopper pressure.

- We will use white-on-black plastic mulch instead of black. With the white side up, we hope there will be far less head build-up under our row covers as the temperatures begin to rise.

- We will rotate to an adjacent, half-acre field that has been planted in cover crops for the past 18 months, including a mix of clovers, hairy vetch, and oats. We will make additional soil amendments this winter to ensure even and adequate fertility. We will also increase our foliar feeding regimen during the 2017 growing season.

- We will plant larger sunflower transplants several weeks earlier to encourage faster establishment, so that the plants are available to provide better shading of the tomato plants at the appropriate time. We will also experiment with direct seeding some sunflowers with seed that has been stratified over the winter. The stratification (cold treatment) will encourage higher and faster rates of germination.

Conclusion:

Due to early season setbacks, it became difficult to evaluate the impact from curly top disease with so many other factors at play. Although our results were confounded by various issues and do not support our hypothesis yet, we observed first-hand that soil fertility dramatically impacted plant health, suggesting that soil quality supersedes other considerations. We have some evidence that shading with shade cloth provides tomato plants with protection from New Mexico’s harsh sun and dry heat, resulting in healthier overall plants and higher yields. However, we also saw some evidence, although not overly convincing, that shading reduces beet leafhopper feeding and rates of curly top infection. So far, it does not appear that interplanting tomatoes with sunflowers provides the same or better shade protection than shade cloth. The results also support observational evidence that the timing of planting (an unpredictable dance with Mother Nature) and getting the plants off to a strong start are critical. We believe that once we have mitigated the confounding factors that impacted our research in year one, we will be able to draw a more convincing conclusion about shading and curly top virus in year two.

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

Collaborators:

Albuquerque Area Extension Agent

New Mexico State University

1510 Menaul Blvd., NW

Albuquerque, NM 87107

Office Phone: 5052431386

Website: http://bernalilloextension.nmsu.edu