Project Overview

Annual Reports

Commodities

- Agronomic: sunflower

- Vegetables: tomatoes

Practices

- Crop Production: intercropping, tissue analysis

- Education and Training: farmer to farmer, on-farm/ranch research

- Farm Business Management: feasibility study

- Pest Management: biological control, disease vectors, field monitoring/scouting, physical control, row covers (for pests)

- Production Systems: permaculture

Summary:

TomatoCulture Year Two Annual Report - 2017

Summary and Grant Recap

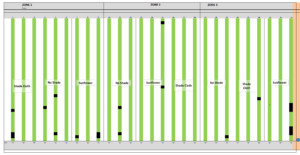

This report comprises our second-year analysis of curly top virus (“curly top”) and its impact on plant outcomes among TomatoCulture heirloom tomatoes for the 2017 season. The farm is in Albuquerque’s North Rio Grande Valley. Curly top is transmitted by the beet leafhopper, the only known vector for this disease. We planted 37 different varieties of tomatoes (one hybrid, the rest heirlooms) into one of three zones, each divided into three different fields with different growing conditions: Either shaded with 30% shade cloth, in open sun, or interplanted with sunflowers for a dappled shade effect (Figure 1). We analyzed rates of curly top infection among the plants by field and condition, testing the hypothesis that shaded plants would have a decreased incidence of curly top due to the beet leafhoppers’ preference for feeding in bright sunlight. A subset of this hypothesis was to test if interplanting with sunflowers provides the same or better results than shade cloth in terms of deterring beet leafhopper feeding and reducing curly top disease. We also analyzed whether the shaded plants would be healthier overall and produce more fruit.

Figure 1 – 2017 three zones with three growing conditions in each.

Note – Black squares represent the locations where plant death occurred from curly top virus.

Project objectives:

Our objectives did not change from year one:

- Determine if light shading deters the beet leafhopper from feeding on tomato plants and spreading the BCTV infection. Working with the Bernalillo County Extension service, TomatoCulture will monitor plant infection and mortality rates for each of the test plots and periodically send plant tissue samples to the plant diagnostics lab through NMSU to confirm BCTV infection.

- Compare shade cloth with inter-planted sunflowers to see which shading system works best in terms of effectiveness and cost. If we can confirm protection from shading, it will be valuable to understand if inter-planting tall sunflowers (assumed to be more cost effective) provides the same, less or greater benefit as fabricated shade cloth.

- Measure and compare plant yields to determine if there is a positive ROI for the increased labor and material cost associated with each shading system. Monitoring and comparing the fruit yields across the three different test plots will provide valuable information about the feasibility of an environmentally sound approach to a pest that can be very destructive to high-value cash crops.

- Determine if shading to control BCTV has other impacts, good or bad, on overall plant health and tomato yield. Some believe that shading sun-loving tomato plants slows plant growth, delays flowering and reduces yield. This experiment will allow us an easy way to test a secondary hypothesis: that shading in NM, which is at higher elevations and has high solar radiation, actually leads to less stressed plants, greater fruit set, and lower disease pressure overall.