Final report for LNE21-421

Project Information

There are urban farms located in every major city throughout New York, providing food security, nutrition and environmental benefits to their communities. Urban growers face unique pest management challenges including limited space, proximity to neighbors, constructed soils, early exposure to invasive pests, and climatic challenges. These challenges historically have not been addressed through research or extension efforts in our region. A total of 15 farms across New York City (NYC), Buffalo, and Rochester hosted demonstration trials that implemented non-chemical pest management strategies such as host resistance, release of natural enemies, conservation biological control, pest exclusion, adjusted planting dates, and regular scouting and trapping. The on-farm trials provided growers the opportunity to observe the benefits of pest management practices first-hand and allowed us to document the impact of these management practices on urban farms with a focus on profitability, feasibility and yields. Farms that implemented a sustainable pest management practice in this project saw on average an $30,404/acre increase in revenue. Ten growers reported implementing these sustainable pest management strategies contributed to the social mission of their farm. We shared project results with growers through workshops, farm tours, and written resources including newsletter articles and factsheets. Throughout the project, in person and virtual workshops were held to facilitate peer to peer learning. We hosted or participated in 39 workshops throughout the project for 71 hours of programming reaching 1077 participants. Workshops concentrated on topics including pest and disease identification, scouting, cultural, mechanical, and biological controls, and creating beneficial habitat for natural enemies. In the final year of the project, we developed a New York Urban Farms Sustainable Pest Management factsheet series with case studies highlighting pest management techniques from our demonstration trials. Techniques featured include row covers, disease resistant crop varieties, biocontrols and taking a ‘brassica break’. To increase accessibility, factsheets were translated into Spanish, Arabic, and Chinese (Mandarin). The project team conducted 684 farm consultations throughout the project. Results and events from this project were shared in over 30 newsletter articles and 60 social media posts estimated to reach over 7000 people.

15 farmers in Buffalo and NYC will see an increase in revenue of $2000/acre as a result of implementing sustainable pest management practices for urban agriculture; and/or report quantifiable improved success in their social missions such as number of youths gaining pest management skills or diverse audiences reached. Increase in revenue will be the result of higher quality vegetables, improved yields, and decreased labor on pest management and sorting. This project will reach a diverse farmer base including minority and female farmers, new and beginning growers, and youth.

While there is no USDA Census data that reports on Urban Agriculture, urban farms are present in each of the 13 states in the NESARE region. In NYS alone, there are an estimated 75 urban farms. These farms may range in size from 0.25 to 2 acres. Urban farmers face unique challenges with pest production that are not extensively addressed through research or extension efforts. Urban soils have been heavily influenced by human activities such as construction, vehicular activity, or industrial activities and the status and health of urban soils influences the type of production urban growers engage in and how they manage pests.

Urban farms, unlike small rural farms, are surrounded by community gardens, home gardens, and school gardens. The concentration of these micro-production sites may increase the number and type of pests that urban farmers must battle. Close proximity to home gardens may increase the number of suitable host plants for insects and diseases and provide opportunities for pests to overwinter. Cities are often ports of entry and urban farms may be the first to be exposed to new, exotic pests. Urban communities are more demographically diverse than rural areas and urban farms often strive to grow culturally relevant foods for their neighborhoods. This may mean growing crops that are not typical for that climate and very little may be known about managing pests or diseases of these new crops. Urban centers are well known to be heat islands, in that the temperature of cities is often a few degrees warmer that surrounding areas due to the presence of impervious surfaces and buildings.

Cooperators

Research

This project had on-farm research in a demonstration function. As each demonstration trial was co-created with growers to create site-specific management plans, we did not endeavor for statistically valid experimental design. To keep reporting of this project consistent with past progress reports, research activities and conclusions organized by pest management practice trialed are reported in this section.

Project Note: In the second year of this project (2022), there was a seven-month gap in project management due to personnel changes. This resulted in limited communication and impact measurement for on-farm demonstration trials in Buffalo. In 2023 and 2024, we conducted an urban farm scouting program with farms in Buffalo and Rochester.

Releasing Ladybeetles to Manage Cabbage Whitefly

At Red Hook Farms and East New York Farms in NYC, we trialed Delphastus catalinae ladybeetles as a biocontrol for cabbage whitefly (Aleyrodes proletella), the most damaging pest of brassicas at both participating farms as well as many other farms and gardens in NYC. Delphastus is routinely used for control of other whitefly species in greenhouse settings, but we found no published research investigating Delphastus for control of cabbage whitefly.

At both farms, 150 to 300 Delphastus adults were released on 7/1/21 and 7/15/21 in selected locations within kale and collard plantings under a section of row cover which the farmers removed 7 to 12 days later. Whitefly infestation levels were estimated on a 0 to 3 rating scale at the time of release, where 0 = no whitefly nymphs or adults present on leaf undersides and 3 = severe infestation and unmarketable leaves; ratings were taken throughout the planting, averaging the values of 6 leaves sampled at each location. Using a hand lens, 3 leaves at each sampling location were briefly scouted for presence of Delphastus adults or larvae (Figure 1). In 2022, we repeated the trial releasing Delphastus catalinae ladybeetles for control of cabbage whitefly (Aleyrodes prolotella) on the same farms.

In 2023, we repeated the trial releasing Delphastus catalinae ladybeetles for control of cabbage whitefly (Aleyrodes prolotella) at Red Hook Farms and Pink Houses Community Farm (East New York Farms). At Red Hook, this was done as a controlled experiment: 6 sections of a row of curly kale were covered in insect exclusion netting for 7 days, with one bottle of Delphastus (estimated 40 to 90 surviving adults per bottle) released under each of 3 sections, and the remaining 3 serving as the control plots. At Pink Houses, these were released later in the season. At the first order of Delphastus, no whiteflies had yet appeared at Pink Houses, perhaps due to an effective “Brassica Break” and a later Delphastus release was attempted.

Adjusting Soil pH to Manage Pillbugs

Several NYC urban farms reported pillbug (aka roly-poly, Armadillidium vulgare) damage on radishes and hakurei turnips in spring 2021, including Edgemere Farm, where marketability of spring radishes was reduced by at least 50%. The soils at all these locations were high in organic matter (>8% OM) with a pH of at least 7.0, in some cases above 7.5. Some research has suggested pillbug root-feeding activity increases with higher soil pH.

On 10/6/21, soil testing was done at Edgemere Farm on two rows which were to be planted into radishes and/or hakurei turnips in spring 2022. Elemental sulfur (to lower pH) was then applied to one of the rows at a rate of 1.5 lbs per 100 square feet. The other row was designated as a control with no sulfur added.

In spring 2022 before planting, elemental sulfur application was repeated on the test area at a rate of 1.5 lbs per 100 square feet. In June 2022, soil testing was repeated to measure soil pH and a pillbug damage assessment was conducted on radishes and turnips.

Taking a “Brassica Break” to Reduce Pest Pressure

Several of the most prominent pests of brassicas in NYC (cabbage whitefly, harlequin bug, and flea beetle) overwinter on brassica crops left standing throughout the winter for year-round harvest, a common practice of urban farms and gardens, sometimes for seed saving. Four farms participating in this project—and subsequently, at least three additional urban farms—implemented a period of at least two weeks with no brassicas present on the farm in winter or early spring of 2022; or, as we began calling it, a “brassica break.” In 2023, at least 9 farms reported implementing a “Brassica break” of some form. In 2024, at least 10 farms reported implementing a “Brassica break” of some form.

Resistant Cucumber Varieties for Downy Mildew

The project team has documented downy mildew of cucurbits to be a significant disease on NYC, Buffalo and Rochester farms. About 1/3 of urban farmers surveyed in NYS reported Downy Mildew of cucurbits as a top disease on their farm. In 2023, two East New York Farms- Pink Houses Community Farm and United Community Centers Youth Farm- trialed a downy mildew resistant cucumber variety (Brickyard) alongside non-resistant varieties (Longfellow and Marketmore 76).

Spotted Lanternfly Management

Between 2021 and 2023, spotted lanternfly (SLF) rapidly emerged as an invasive species in NYC. While SLF was already known to be a major pest of grapes, in 2021 the prevailing knowledge was that SLF does not damage vegetable crops. In 2022, we found SLF nymphs in high numbers on cucumbers and okra, with evidence of associated decline in the cucumbers (Figure 2). We also saw many SLF nymphs and adults in fruit trees, including figs, a common tree of NYC gardens, farms, and backyards.

In 2023, we trialed low-impact, low-cost SLF traps by using yellow insect sticky tape at two NYC farms. Some of the recommended SLF traps for trees had a history of excessive bycatch, including birds and frogs. We chose a narrow yellow tape (2” width) in hopes of avoiding this. On 6/16/23, we applied individual sticky collars around the bases of cucumber and okra plants, using (supposedly) water-resistant cardboard tubes at Snug Harbor Heritage Farm. Additionally, we trialed applying tape directly to branches of a fig tree experiencing heavy infestation of SLF nymphs at Red Hook Farms.

Releasing Biocontrols and Other Tactics to Manage Aphids

From 2021-2023, several farms in Buffalo reported aphids in high tunnels on tomatoes and cucumbers as a major pest.

Urban Fruits and Veggies (UFV) is an urban farm on the East Side of Buffalo growing on ¼ acre in raised beds and in one greenhouse. They focus on mixed vegetable, herb and fruit production with plans to expand hydroponic and greenhouse production at future sites. In 2021, UFV reported high aphid pressure on peppers and brassicas. Aphid populations quickly built up on pepper and brassica transplants in the high tunnel prior to planting outside. We recommended releasing biocontrols to bring the population below the economic threshold. Ladybeetles and lacewing larvae were purchased and released.

In 2022 at UFV, we repeated releasing ladybeetles in the high tunnel for the control of aphids. Ladybeetles were released two times- once in July and once in August. They also tested using insect exclusion netting in the high tunnel and outside raised beds to help decrease pest pressure and support biocontrol release efforts.

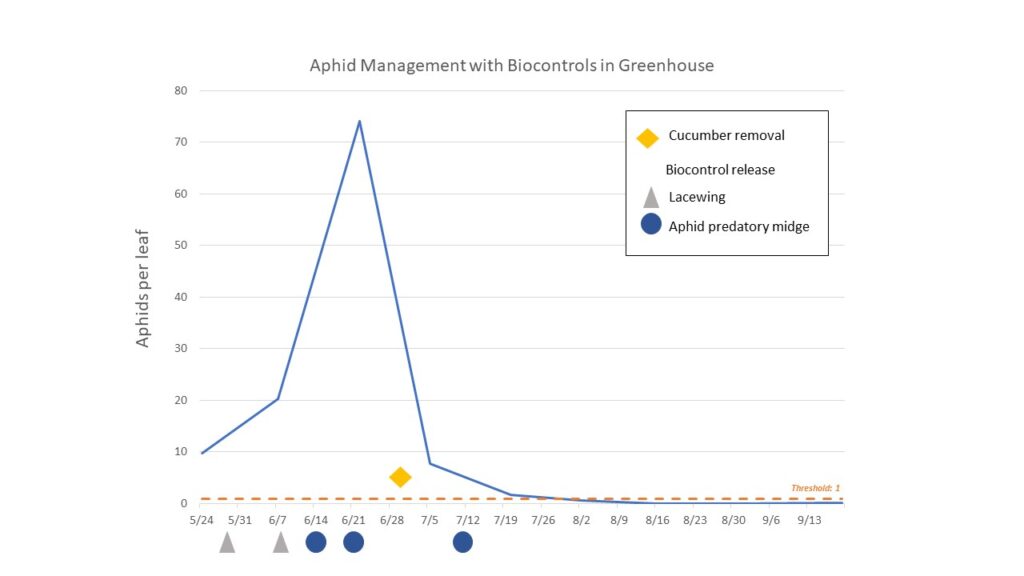

In 2023, UFV reported high aphid pressure on tomatoes and cucumbers in their greenhouse. Lacewing larvae (Chrysoperla rufilabris) were released 2x during end of May and early June to be used as a quick knockdown of the aphid population. Aphid predatory midge (Aphidoletes aphidimyza) was released 3x in middle of June and early July as a more sustained biocontrol approach throughout the season. According to project advisor, Carol Glenister, aphid predatory midge has been reported to reproduce successfully and maintain its population throughout the season. Prior to biocontrol introduction, we did an aphid count on greenhouse tomatoes and cucumbers on 5/24/23. After biocontrol introduction, we did aphid counts 8x throughout the season every two weeks from 6/7/23 through 9/19/23. Aphid counts were done by counting the number of aphids on three randomly selected leaves per plant for six plants in cucumbers and six plants in tomatoes giving 36 leaves in total. Aphid counts are a measure of the average aphid number on a leaf (total aphid number divided by total number of leaves). Our scouting program used an action threshold of one aphid per leaf. Due to high aphid numbers, the farmer decided to terminate the cucumber crop on 6/29/23. After this, the remainder of aphid counts were done only on the tomato crop.

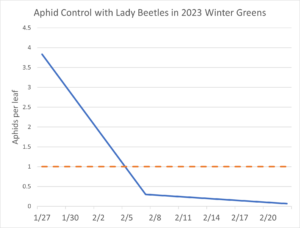

The Brewster Street Farm with Journey's End Refugee Services offers the Green Shoots for New Americans Program which facilitates urban farming opportunities on Buffalo’s East Side. The farm grows numerous culturally important vegetables from farmer participants immigrating from Nepal, Afghanistan, Bhutan, and more. In 2022, aphids were noted to be present in the farm high tunnel before spring planting. After planting, the farm released lady beetles 2x in June and poured diatomaceous earth 1x on soil to manage aphid populations. In addition, we trialed releasing Aphidoletes aphidimyza gall midges two times (once in July and August) for additional control of aphids. Infested crops were removed in early fall 2022, but some aphids remained most likely surviving on weeds and in the soil. In winter 2023, we worked with the farmer to manage aphids in their high tunnel winter greens production. We released two pints (18000 adults) of adult lady beetles (Hippodamia convergens) under row cover in plantings of winter greens and herbs on 1/27/23. This rate is very high for the 1800 sq ft that we were treating. In future work, we hope to see similar results with lower rates, which would be more cost effective. Our scouting program used an action threshold of one aphid per leaf. We did aphid counts 4x throughout the winter from 1/27/23 through 3/10/23. Aphid counts were done by counting the number of aphids on three randomly selected leaves per plant for 20 plants giving 60 leaves in total. Aphid counts are a measure of the average aphid number on a leaf (total aphid number divided by total number of leaves).

The Massachusetts Avenue Project (MAP) farm located on Buffalo's West Side runs a year-round youth employment program building youth leadership skills through farming and other civic engagement programs. They grow a diversity of vegetables, fruits, flowers and herbs; they keep chickens and bees; and create numerous value-added products. In 2022, we trialed releasing Aphidoletes aphidimyza gall midges one time in the high tunnel for aphid control. After discussions with the farmer, we focused on trialing methods for managing flea beetles in 2023.

Using insect exclusion netting to manage cucumber beetles

Common Roots Urban Farm is a one-acre urban farm in Buffalo producing diversified vegetables, fruit, flowers, and honey. In 2021, cucumber beetles were reported to be a significant pest on squash and cucumber. In 2021, we installed insect exclusion netting (ProtekNet Exclusion Netting, FIINTE3, 2x50-47 (Dubois Agrinovation)) on their caterpillar tunnel for exclusion of cucumber beetles on squash and cucumbers. Insect exclusion netting was applied prior to cucumber beetle emergence. Twospotted Spider Mite (TSSM) damage was noted to be significant in the latter part of the 2021 season.

We were pleased to document during the 2022 growing season that Common Roots implemented insect exclusion netting on their caterpillar tunnel on their own to manage cucumber beetles on squash and cucumbers. Insect exclusion netting was applied prior to cucumber beetle emergence, and they grew parthenocarpic (self-fertile) cucumber varieties. This adoption comes after an on-farm project demonstration in 2021. In addition, based off previous communication with project team members, Common Roots released a biocontrol mite predator, Phytoseiulus persimilis, one time early in the growing season to manage TSSM damage.

Swede Midge Management

An unexpected development in this project was routine scouting showed swede midge (SM), an invasive insect pest of brassicas, to be a severe challenge for urban growers and present on majority of farms in Buffalo and Rochester. Due it to its small size and somewhat vague symptoms, swede midge can be hard to identify and is sometimes called an “invisible pest.” To help us make and evaluate management decisions, we monitored its population throughout the season using traps. Traps contained a pheromone lure that attracts male swede midge adults. Swede midge adults begin to emerge in spring, mate, and females lay eggs on the plant. Eggs hatch into larva which feed at the growing point and then jump off the plant to develop into pupae in the soil. The pest can survive and overwinter for up to three years in the soil.

SM has caused so much damage to brassica crops at Common Roots that in 2021 these farmers removed broccoli, brussels sprouts, cauliflower from their crop line-up entirely. In 2021, they rotated their brassica crops as far from the previous year’s planting as possible and covered everything with Proteknet exclusion netting. The netting had to be removed from crops (collards, kale) because the plants were getting too tall for their hoop set-up. Moving forward in the project, they continued to grow the less-preferred brassicas under exclusion netting such as curly kales. Farmers continued to make sure that transplants going under netting were free of worm pests, and ground was free of brassicas for at least 3 years before growing brassicas in the same spot again.

The brassicas grown at UFV were primarily collards, kale, mustard greens, and kohlrabi. Collards have historically been the most effected by SM. In 2020, they moved all brassicas to a location outside of the city (Providence Farm Collective (East Aurora)) in order to get a marketable crop. In 2021, they brought collards back to the UFV site. Significant damage and larvae were observed early September 2021. In 2022, UFV focused on brassica crops in raised beds that have not have brassicas for past 2-3 years and used Proteknet exclusion netting. In 2023, SM damage was observed on collards again at the UFV site.

Brewster Street Farm had significant SM damage prior to this project and SM was observed in the late Fall 2021 brassica planting. Intercropping was a common practice at the farm. Intercropping was done to 1) maximize use of raised bed space; 2) for support of beneficial insects; and 3) to receive benefits from companion planting. However, intercropping made crop rotation difficult when each raised bed may contain crops from different families. SM built up on brassica crops in numerous raised beds across the farm. To manage SM, we implemented an integrated approach – removed late season brassica crop residue and discarded, and applied H. bacteriophora entomopathogenic nematodes to the soil to try to knock down the overwintering population. The entomopathogenic nematodes fed on a diverse range of soil dwelling pests, including SM. Nematodes were applied twice- once in Fall 2021 and in Spring 2022. Nematodes were watered in with a pump sprayer to raised beds. Raised beds were pre-wetted to allow better survival and movement of nematodes through the soil profile.

5 Loaves Urban Farm is a farm ministry connected to the Buffalo Vineyards Church. Throughout this project, they had roughly ½ acre in production and grew on 4 separate lots on the West Side of Buffalo. They grow a diversity of vegetables, fruits, and herbs; keep chickens and bees; and create numerous value-added products. The farm was noted to have SM damage on their brassicas in mid-summer 2021. Damage was quite extensive on kale, collards, broccoli, and cauliflower. SM damage was found on 2/2 lots those brassicas were grown on. Brassicas were grown under row cover, but the fabric was torn in numerous areas. In mid-Summer 2021, we began monitoring the population of SM on the main lot. SM pheromone traps were collected on a biweekly basis for 2 months from 7/30/21 to 9/8/21. We recommended rotating away from brassicas where possible and prioritizing brassicas on the most recently acquired lot. In addition, we recommended to cover with insect exclusion netting. In 2023, 5 Loaves served as a scouting location and SM damage was noted on kale, broccoli, collards, and cabbage.

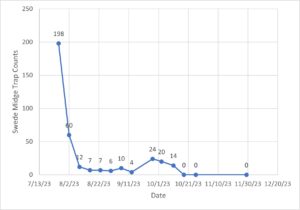

WestSide Tilth (WST) is a one-acre urban market garden farm in Buffalo producing diversified vegetables, herbs, and flowers. In 2023, SM larva and damage on collards was noted on 6/16/23. The farmer reported struggling with SM on various brassicas including kale, kohlrabi, collards, and cabbage for the last few years with damage seeming to increase each year. We began monitoring the population of SM on the urban farm using two traps in July 2023. SM pheromone sticky cards were collected on a weekly basis from 7/20/23 until 9/13/23, then on a biweekly basis until 10/26/23, and the final sticky cards were collected on 11/29/23. The two traps were periodically moved to different beds with and without insect netting as crops were harvested and planted. One trap was moved into a collards planting under insect netting on 8/16/23 and remained there for the duration of monitoring.

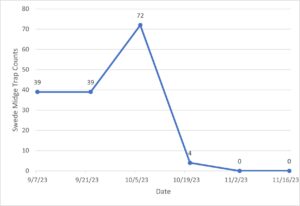

Foodlink Community Farm (FLCF) is a 1.6-acre urban agriculture campus in Northwest Rochester containing a commercial farm producing vegetables, fruit and honey, and a large community garden serving 70 multigenerational New American families. Extensive SM damage was noted at the end of June 2023, we noted unusual growth patterns, brown corky scarring, soft rot at the growing point in collards and kale. At the end of the season, the farmer reported losing four raised beds and over 100 lbs of brassica crops due to SM. In August 2023, we began monitoring the population of SM using one trap in a raised bed containing brassicas on the urban farm. SM pheromone sticky cards were collected on a biweekly basis for 3 months from 8/25/23 through 11/17/23.

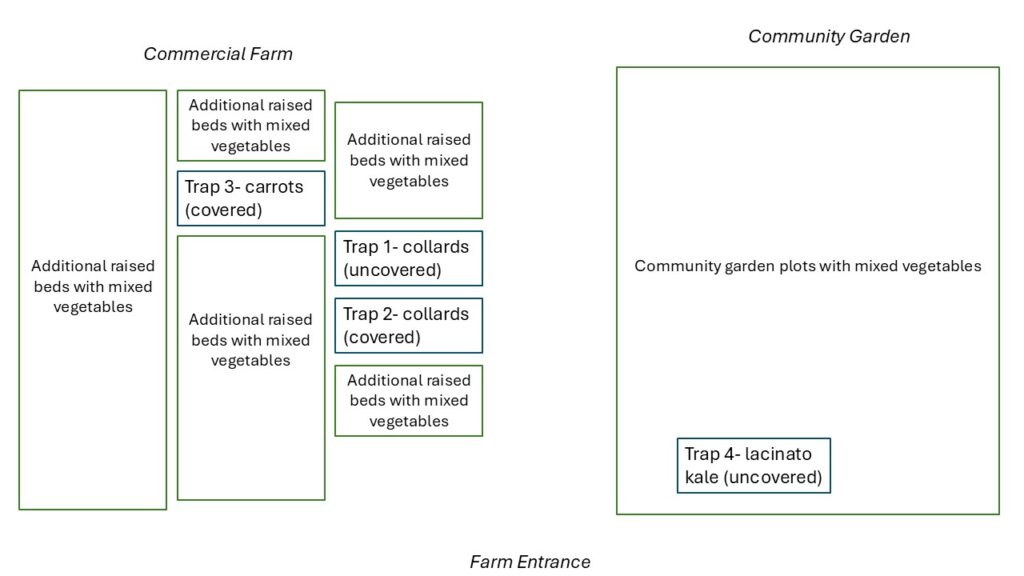

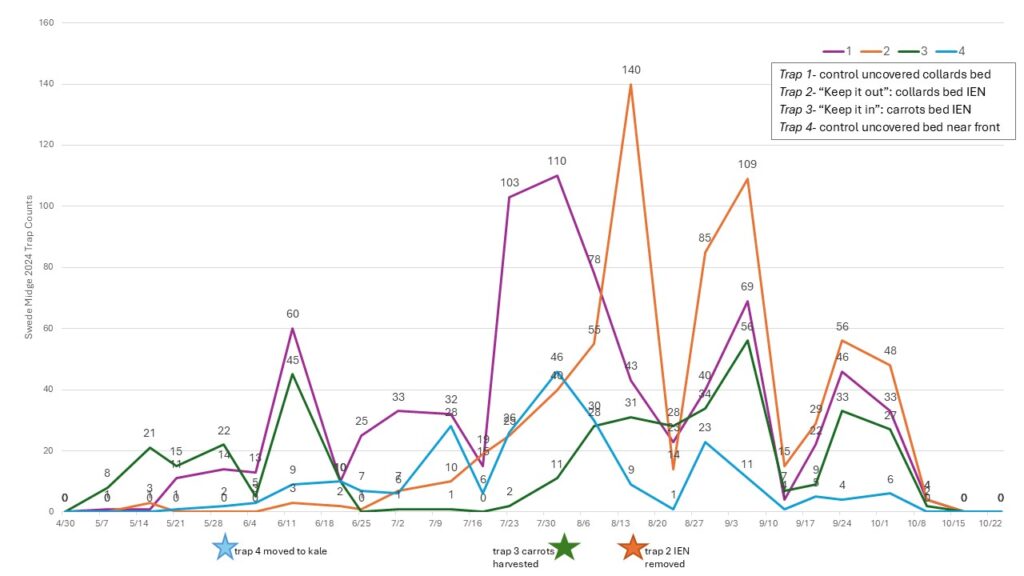

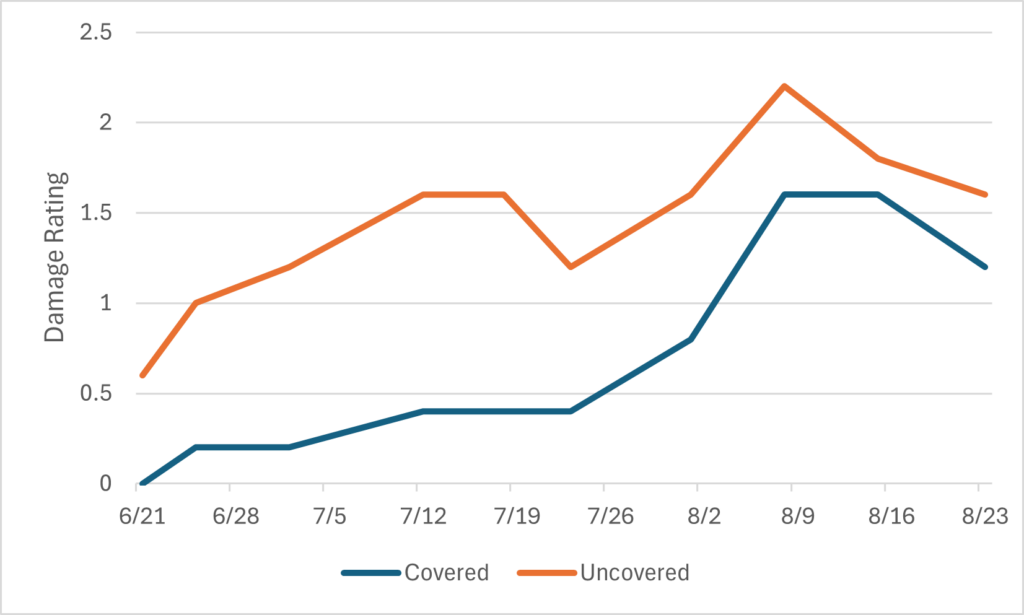

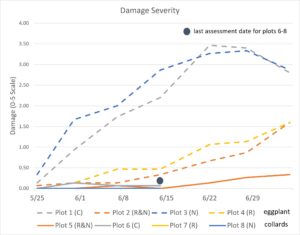

In 2024, FLCF hosted a demonstration trial looking at strategies to manage SM on collards (Figure 3). We trialed multiple approaches to disrupt swede midge’s life cycle and lessen its damage on brassica crops. First, we used crop rotation planting brassicas in beds that have not had brassicas in them for at least three years. Second, we used insect exclusion netting in two ways to serve as a physical barrier to either contain pests (“keep it in”) or prevent them from getting to plants (“keep it out”). In Spring 2024, we set up four traps around on the farm to demonstrate these approaches in various ways (Figure 4). Traps 1 and 2 were in raised beds next to each other, both beds had not had brassicas in them for at least the last three years. Both beds were planted with the same variety of collards transplanted on 4/17/24. Trap 1 bed was the uncovered control and trap 2 bed was covered with insect exclusion netting (ProtekNet Exclusion Netting, 25 gram, 2.1 meter width) at planting. Trap 3 was placed in a raised bed with an existing overwintering swede midge population, planted with carrots, and covered with Proteknet exclusion netting. Trap 4 was placed in a raised bed planted with kale and located farther away on the edge of the farm in the community garden to monitor background swede midge population. Traps were set up on 4/23/24 and pheromone sticky cards were collected weekly basis for 6 months until 10/24/24. Lures were replaced monthly on 5/21/24, 6/21/24, 7/18/24, 8/23/24, and 9/24/24. Swede midge damage assessments were conducted weekly on collards from 6/21/24 through 8/23/24. Damage severity was assessed on five randomly selected plants per raised bed. Damage per plant was rated on a 0-4 scale corresponding to the severity of symptoms per plant and its marketability (0 = no damage; 1 = minor damage, plant unaffected and marketable; 2 = moderate damage, plant quality and/or yield reduced but marketable; 3 = major damage, remnants of growing point, not marketable; 4 = severe damage, i.e. blind head). Harvest yields were measured regularly from 6/11/24 through 10/29/24.

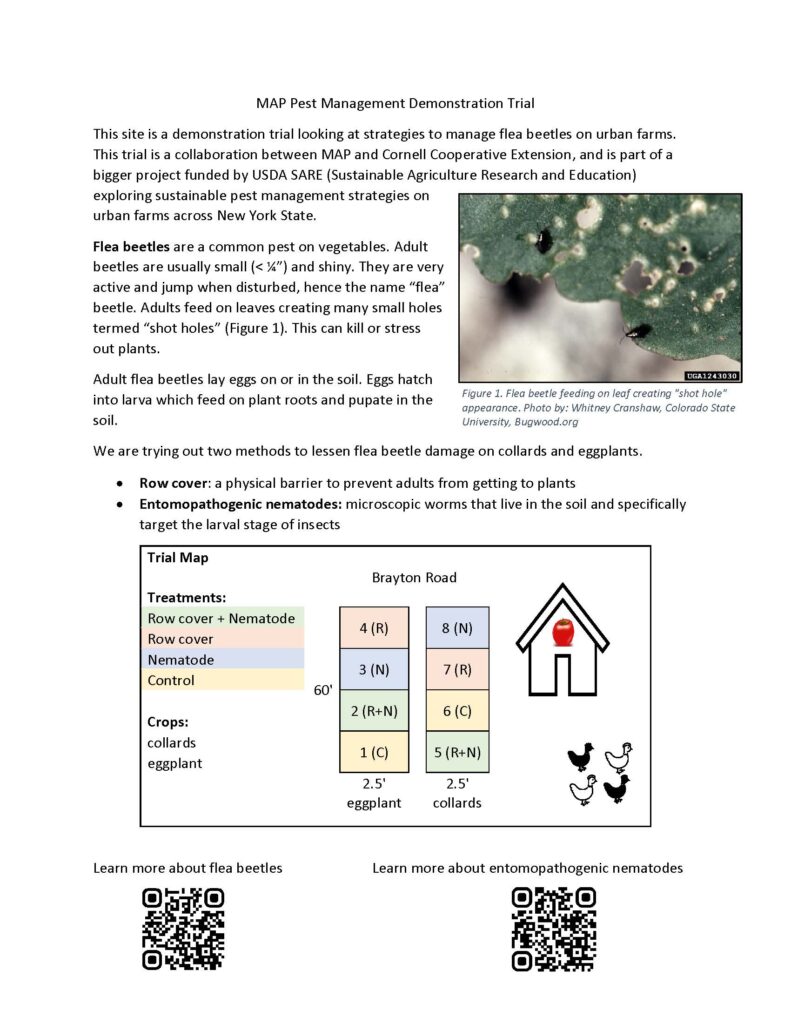

Using Row Cover and Entomopathogenic Nematodes to Manage Flea Beetles

MAP farm manager reported flea beetles as a major pest. In 2023, MAP hosted a demonstration trial looking at strategies to manage flea beetles on collards and eggplant. There were four treatments tested: 1) row cover, 2) entomopathogenic nematodes, 3) a combination of row cover and entomopathogenic nematodes, and 4) an untreated control plot. The trial was set up and planted on 5/17/23 (Figure 5). There were 18 plants in each plot at planting. Row cover used was 0.5 oz and put on at time of planting. Row cover was removed from eggplant plots on 6/22/23 and from collards on 7/5/23. A single entomopathogenic nematode species was chosen for treatment based off conversations with Project Advisor Carol Glenister. Steinernema carpocapsae is a sedentary ambusher species chosen for its ability to withstand lower soil temperatures and availability for purchase. Nematodes were applied in a water solution using a watering can at a rate of 5 million nematodes / 1600 sq ft on 5/17/23 and 5/25/23.

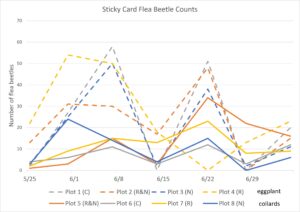

Nematodes were applied in the middle of the day on 5/17/23 and nematodes were applied in the evening on 5/25/23. A yellow sticky card was placed in the middle of each plot. Flea beetle counts and crop damage assessments were conducted weekly from 5/25/23 through 7/5/23. Damage severity was an average of the leaf damage rating for three randomly selected leaves per plant. Damage per leaf was rated on a 0-5 scale corresponding to the percentage of leaf with symptoms (0 = 0%; 1 = 1-20%; 2 = 21-40%; 3 = 41-60%; 4 = 60-80%; 5 = 80-100%). Our last damage assessment for three out of four collard plots took place on 6/14/23. These plots had plant loss due to a chicken feeding event. Harvest yields were measured regularly from 7/5/23 through 11/1/23.

Our work in this project was demonstration focused, not pure research, as we ‘demo-trialed’ pest management techniques that already have proven potential for success. In this approach, although we do not replicate treatments to analytical levels, we employ rigorous data collection to support adoption. What was unique was the urban setting in which we adapted and deployed the management practices, as well as the site-specific pests and practices. However, at some sites we were able to collect quantifiable data that provided a very applied research approach with the ultimate goal of demonstrating impacts to the farmers.

Releasing Ladybeetles to Manage Cabbage Whitefly

Scouting on 7/15/21 and 8/18/21 showed slightly less whitefly pressure near areas of Delphastus release. On one farm, there was a rating of 1.5 near the release location versus 2 to 2.5 at the other locations sampled. At the other farm, there was a rating of 2 near the release location versus 2.5 at most other locations scouted. Three Delphastus larvae were identified on collard leaves at one farm on 9/23/21, including clear evidence of cabbage whitefly predation. The presence of Delphastus larvae and evidence of cabbage whitefly predation, along with lessons learned about improving effectiveness of releasing Delphastus in outdoor settings and farmers’ stated interest in this biocontrol as an IPM strategy, suggested that we should expand on this trial in 2022.

In 2022, we trialed releasing Delphastus catalinae ladybeetles again on the same farms for control of cabbage whitefly (Aleyrodes prolotella). As in 2021, we found Delphastus larvae on brassicas (evidence of successful reproduction, since Delphastus are released as adults), with clear signs of predation of cabbage whitefly nymphs. However, as in 2021, we did not find conclusive evidence of a corresponding reduction in whitefly damage.

In 2023, at Red Hook, a count on 8/11/23 showed no significant difference in whitefly adults or nymphs between treatment and control plots. Treatment sections had significantly fewer egg clusters at 26 per leaf, compared to 41 per leaf in the control sections. This squares with the Delphastus supplier’s comment to us that the species (nymphs and especially adults) preferentially predates eggs versus nymphs or adults. On the 18 leaves scouted in treatment sections, we found only 3 Delphastus larvae and 1 adult, and none in the control sections.

Several Delphastus larvae were identified on leaves about 3 weeks after the biocontrol release at Pink Houses in 2023. Though this was not done as a controlled experiment and it was unclear whether the ladybeetles were effective as a control. Overall, while we continue to find ample evidence that Delphastus predates on cabbage whitefly and reproduces successfully while doing so, it remains unclear how to effectively use Delphastus as a control for cabbage whitefly.

Detecting Parasitoid Wasp of Cabbage Whitefly

An unanticipated finding in 2022: In the process of scouting for cabbage whitefly predation and Delphastus, we noticed the presence of a parasitoid wasp (Figure 6) which appeared to be parasitizing cabbage whitefly nymphs; the adult wasps were very common in the scouted plantings, with as many as 10 per leaf. The wasp resembled Encarsia formosa, a commonly purchased biocontrol of greenhouse whitefly, but we believed it to be Encarsia tricolor, which we subsequently learned has been observed as a naturally occurring cabbage whitefly parasitoid in Eurasia. A search of academic databases turned up no other documented observations of Encarsia tricolor parasitizing cabbage whitefly in the Americas.

In Fall 2023, we found and collected more unidentified Encarsia specimens at Pink Houses Community Farm. None were found at Red Hook Farm, as in past years, possibly due to their more regular regime of spraying insecticidal soap to suppress whiteflies (once weekly after first appearance, with an improved nozzle and new battery-operated backpack sprayer). Adult Encarsia were collected in 90% ethyl alcohol and sent to a USDA ARS research partner (Luke Kresslein, housed at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C.), a taxonomist specializing in Encarsia, for identification. He reported that while the species is likely a close relative of Encarsia tricolor, it was determined to be a previously undescribed species. Project team members intend to submit a paper to describe and name it after the completion of this project. We brought some parasitized whitefly nymphs indoors and set up two insect rearing pens: one for Encarsia and cabbage whitefly together, and one for additional cabbage whitefly to provide a continual food source for the Encarsia. In late November, the whitefly population had increased enough to threaten the host plant’s health. On 12/1/23, the first confirmed Encarsia adult appeared. By 12/4/23, many more Encarsia adults had emerged, at least 4 per leaf. By 12/12/23, the whitefly population had crashed, with no egg clusters found in the rearing pen and very few adults remaining. Closer inspection showed that on some leaves, nearly every whitefly nymph had been successfully parasitized. While in a controlled environment, this demonstrated the potential of this Encarsia species to control cabbage whitefly.

Encarsia colonies were found at a new location in Brooklyn in 2024, on kale and collards, over 3 miles from the other sightings, suggesting the species may be more widely distributed and better established than previously known.

Adjusting Soil pH to Manage Pillbugs

After the second sulfur application in spring 2022, the treatment area’s pH was measured at 6.8, compared to 7.2 for the control area. While pillbug damage was reduced in general compared to 2021 (Figure 7) (possibly due to drier weather), Edgemere found nearly no pillbug damage in the treatment area in 2022 (Figure 8), compared to 15% of radishes damaged in the control area (Figure 9).

With an added yield equivalent to 375 bunches per acre, at $4/bunch, this amounts to $1,500/acre added revenue per year. The farm continued to add elemental sulfur ahead of radish plantings in 2023 and 2024, again finding nearly no pillbug feeding damage in treated areas each year. These results show promise in reducing pillbug feeding damage by lowering soil pH with elemental sulfur in soils with high levels of organic matter (>8% OM). With similar results achieved in 2022, 2023 and 2024, total added revenue at this farm was around $4,500/acre.

Taking a “Brassica Break” to Reduce Pest Pressure

In 2022, demonstration trials of a new approach to reduce brassica pest pressure was particularly successful. At all seven of farms implementing a brassica break, the first appearance of the previous years’ most significant spring brassica pests—cabbage whitefly, harlequin bug, or flea beetle—was delayed by two to seven weeks. This resulted in large increases in marketable product during brassica plantings’ head start. For example, at Kelly Street Garden, 163 lbs of collard greens were harvested before the first appearance of cabbage whitefly nymphs; the prior year, fewer than 35 lbs of collards were harvested before whitefly nymphs began affecting marketability. This 128 lb increase is over $350 more in revenue and amounts to over 23,000 lbs per acre and over $40,000 per acre in revenue.

In 2023, all 9 farms reported a later onset of cabbage whitefly, from 2 to 8 weeks. Two farms that used a modified Brassica break by leaving row cover on all brassicas until late June also reported a near absence of flea beetles, aphids, or harlequin bug until fall.

In 2024, 10 farms implemented a winter and/or spring Brassica Break and reported cabbage whitefly appearances delayed 3 to 7 weeks, with significant reductions in cabbage aphids and flea beetles as well.

Resistant Cucumber Varieties for Downy Mildew

Both farms trialing a downy mildew resistant cucumber variety (Brickyard) alongside non-resistant varieties (Longfellow and Marketmore 76) saw straightforward results. Cucurbit downy mildew caused rapid plant decline in the Longfellow and Marketmore beginning in late July 2023, with nearly no yield after 8/15/23, while Brickyard continued producing until mid-September. Both farmers intend to expand use of DM resistant cucumbers in the future.

Spotted Lanternfly Management

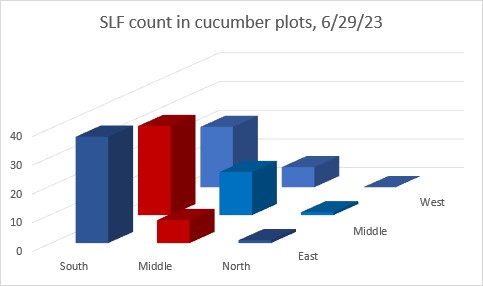

In 2023, while trialing low-impact, low-cost SLF traps, NYC experienced two heavy rain events between 6/16/23 and when we returned to check the traps on 6/29/23 at Snug Harbor. The tape had come unattached from most of the cardboard collars. The cucumber traps also were insufficient due to many points at which weeds reached above the collars, providing alternate routes for nymphs to crawl onto the cucumber plants and the trellising. That said, there may have been some reduction in SLF nymphs in one treatment section (bottom center, or “East-Middle,” in Figure 10). On okra, plants with sticky tape collars average 1.3 SLF nymphs per plant on 6/29/23, compared to 1.6 per plant on plants without traps, possibly indicating some effectiveness, but probably not justifying the labor of attaching the traps.

However, at Red Hook, we did see promising results on the fig tree (Figure 11). Although we were unable to get a thorough count of nymphs on the branches, we observed that of the 6 branches protected by a sticky tape collar, only 1 had SLF nymphs present on 6/29/23, while the majority of neighboring branches had at least 10 nymphs per branch. Although only one nymph was actually seen stuck to the tape, we watched several nymphs approach the sticky tape, then turn around. Even when attempting to force the nymphs to cross the tape by “herding” them down the branch with a hand, when they reached the tape, they preferred to walk around or even over our hand rather than venture onto the tape. This suggested that yellow sticky tape may be effective as a low-cost barrier for keeping SLF nymphs off of trees; at least for fig trees, which have smooth bark that allows the tape to stay attached for several weeks.

Releasing Biocontrols and Other Tactics to Manage Aphids

With using an integrated pest management approach of releasing biocontrols and using insect exclusion netting in 2022, Urban Fruits and Veggies (UFV) reported increases in crop yields with 25% increase in crop size, and an increase in crop quality and length of harvest window. UFV farm manager noted a reduction in labor time and costs. Prior to implementing these pest management practices, farm workers would spend 5 hours per week on pest management (observing, strategizing, handpicking) and after implementing these practices farm workers would spend 2 hours on pest management- net decrease of 3 hours per week. This equates to saving over $2200 on labor per year. In 2023, Aphidoletes aphidimyza larvae were observed feeding on aphids on cucumber leaves on 6/22/23 (Figure 12). We saw a decrease in aphid numbers after 4 biocontrol releases and the removal of the cucumber crop (Figure 13). The UFV farm manager noted again a reduction in labor time and costs. The farm manager reported the plants were cleaner with less pests and less money having to be spent on pest control products. He reported saving roughly 15 hours a month during the growing season on pest management in the greenhouse due to the biocontrol release. This equates to saving over $850 on labor during the growing season in 2023.

In 2022, the Brewster Street Farm manager noted the diatomaceous earth possibly had negative effect on lady beetles. The farm manager reported these practices resulted in an increase in crop quality and increased harvest window of high tunnel tomatoes by 4 weeks. The farm manager shared they “would have had to pull all tomato plants in July [2022] if not for the biocontrols.” In winter 2023, lady beetles were still alive and reduced the aphid population by 98.2% by 2/22/23 (Figure 14). On our final check on 3/10/23, we did not see any aphids in the high tunnel.

At the MAP Farm in 2022, no impact was observed from releasing biocontrols. This can partly be due to more communication needed from project members. In 2023, we worked closer with this site and included them in our urban scouting program. After discussions with the farmer manager, we focused on trialing methods for managing flea beetles in 2023.

Using insect exclusion netting to manage cucumber beetles

At Common Roots Urban Farm in 2021, insect netting appeared to provide sufficient protection of squash and cucumber plants from cucumber beetles. However, the cucumber plants did suffer from lack of pollination due to 1) not being a parthenocarpic variety and 2) the exclusion netting further inhibited pollinators from entering the tunnel. To remedy this, Common Roots moved frames of bees into the tunnel. Pollination thereafter seemed adequate but noticeably less. Twospotted Spider Mite (TSSM) damage was noted to be significant in the latter part of the season.

In 2022, Common Roots reported the insect netting appeared to provide sufficient protection of squash and cucumber plants from cucumber beetles. After releasing the biocontrol mite predator, farmers reported they noticed a decrease in TSSM damage and would have released the biocontrol a few more times but cost was prohibitive. Overall, Common Roots reported a 25% increase in cucumber yield in 2022. Prior to this project and implementing these sustainable pest management strategies, Common Roots reported $323 in cucumber revenue. In the second year of this project and after implementing these sustainable pest management strategies, Common Roots reported $1070 in cucumber revenue, a $747 increase in cucumber revenue over the course of this project. In 2023, the farmers at Common Roots took a break from farming to pursue other business opportunities. This increase in revenue was in the caterpillar tunnel which was 700 sq ft, this trial has demonstrated a potential $46485/acre increase in cucumber revenue by using insect exclusion netting on caterpillar tunnels.

Swede Midge Management

In 2021, Swede Midge (SM) was identified as a priority pest on Buffalo farms. Throughout the duration of the project, multiple urban farms implemented recommended SM management strategies. In 2022, UFV reported practicing crop rotation focusing brassica crops in raised beds that have not have brassicas in them for past 2-3 years and used Proteknet exclusion netting. They did not notice significant swede midge damage in 2022.

In 2022 at Brewster Street Farm, all raised beds affected by SM in the first year of this project had late season brassica crop residue removed and discarded. These beds were treated with Heterorhabditis bacteriophora nematodes in Fall 2021 and Spring 2022. In 2022, SM was still present on farm but less damage was observed compared to the previous year.

In 2023, we monitored the populations of SM starting mid-summer at two farms, WST and FLCF. At WST, we saw highest SM numbers in mid-July and the population decreases over the rest of the season with a small spike in late September and going dormant by the end of October (Figure 15). This aligned with typical SM population dynamics observed in our area. In New York, we expect to see peak emergence of adult swede midge from overwintered pupae in late spring. The high SM population in mid-July corresponded with the initial collards planting showing severe damage. The sharp decline in population we speculated is due to timely post-harvest crop destruction by the farmer. We did observe SM on sticky cards in the collards bed under insect netting which we speculated is due to SM already being present in the soil.

At FLCF, we saw moderate SM numbers at the end of August 2023 with a spike in early October which we speculate may be due to warm weather (Figure 16). The farmer saw pest management and educational value in monitoring the SM population. Based off our work in 2023, the farmer stopped growing Red Russian Kale during the summer season and explored new brassica varieties that may be less appealing to SM. In addition, the farmer planned to continue using insect exclusion netting with brassicas, especially in areas that have not have brassicas grown in them for at least 3 years. The farmer shared the trap was a “great teaching tool working with community gardeners and tour groups. It fits in with the growing practices of the farm. It shows the pest is there and is helpful to keep track of pest pressure. It helps to illustrate the importance of knowing a pest’s life cycle when choosing management tools.” The farmer reported on average 25 people visit the farm weekly from school and community groups, with over 1000 people visiting the farm throughout the growing season.

In 2024 at FLCF, trap counts showed the swede midge population fluctuated depending on management strategy used (Figure 17). In our covered carrot bed (trap 3), we saw emergence first which we speculated is due to that the raised bed had a heavy infestation that overwintered. We see the SM population peaked and dropped mid-June remaining low until the carrots were harvested and the netting came off in August. This suggests the potential of using exclusion netting to crash the swede midge population in small scale growing spaces. Carrots showed no damage or reduced yield by being covered. The grower shared that covering the carrot bed with netting did make it harder to weed.

When monitoring background population pressure, trap 4 loosely followed trap 1 trends. Both traps were place in uncovered raised beds in different locations on the farm, yet trap 4 counts remained lower than trap 1 for entire season (Figure 17). We speculate that this may be due to crop type preference for SM- trap 4 was located in a bed planted with lacinato kale and trap 1 was located in a bed planted with collards. Additional speculation includes that SM might have overwintered in the trap 1 bed and not in the trap 4 bed, hence SM mostly stayed put as it was already happily feeding. Unexpectedly, averaging trap count data together, SM population peaked in early September which suggests SM might behave differently on urban farms than rural farms.

In our uncovered and covered collards beds (trap 1 and 2), we saw SM emergence first in the uncovered bed as we would expect. We saw low SM pressure slowly building in the covered bed in May and June. Towards the middle of the season, pressure rose and peaked on 8/15/24 and 9/8/24. Crop damage was consistently lower in the covered plot compared to the uncovered plot throughout the season (Figure 18). We observed crop damage tended to increase when trap counts increased.

We observed higher crop yields and quality on collards grown under cover. Our collards bed with netting produced higher yields than our collards bed without netting. Our collards bed with netting produced a total of 222.6 lbs and our collards bed without netting produced a total of 214.5 lbs. The bed with netting produced 8.1 lbs more than the bed without netting. This farm reported selling a bundle of collards for $2.50 and a bundle is roughly 2 pounds in 2024. This 8.1 lbs yield increase with netting translates to $10.13 increase of revenue. Our plot area was 28 ft2. This trial has demonstrated a potential $15,713 / acre increase in collards revenue by using exclusion netting.

Beyond yields, leaf quality was observed to be better on covered collards compared to uncovered collards, especially earlier in the season. On 7/2/24, a farm volunteer helping to harvest collards in both beds said "I vote for netting, plants are much cleaner, taller and healthier looking.” At the end of the season, FLCF farm manager shared “Although the difference between the covered and uncovered beds was not significant in weight, the quality of the leaf in the covered beds was superior, particularly in the early half of the season. As the summer progressed and insect pressure under the cover increased, the quality of the leaf was nearly equal.”

Future work includes addressing when is best to take off the netting and investigating the best swede midge damage rating approach for various brassica crop types. Throughout the season, other brassica pests were present including imported cabbageworm, diamondback moth and aphids. The farm manager and project team members hypothesized taking the netting off sooner would have reduced later season damage and helped reduce pressure from other brassica pests trapped under the netting. Most research done on swede midge in our area was on heading brassicas. On urban farms, brassicas most grown and affected by swede midge are leafy greens (kale and collards). In 2024, FLCF farm manager developed an SM leaf damage scale that we plan to incorporate in future work (Figure 19).

Using Row Cover and Entomopathogenic Nematodes to Manage Flea Beetles

Eggplant plots without row cover initially showed higher damage levels than eggplant plots with row cover and eggplant damage levels appeared to be evening out among treatments as the season progressed (Figure 20). We hypothesize this could be due to plants growing more leaves. Eggplants showed higher damage levels than collards and flea beetle counts on sticky cards were consistently higher in eggplant plots (Figure 21). We hypothesize this could be due to flea beetle host preference. We believe we observed multiple species of flea beetles on plants and on sticky cards including the crucifer flea beetle, striped flea beetle and eggplant flea beetle. Flea beetles were present on sticky cards in each treatment.

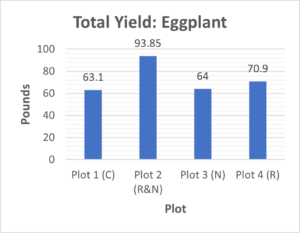

Eggplant plots with row cover produced higher yields than eggplant plots without row cover (Figure 22). Our two plots with row cover produced a total of 164.75 lbs and our two plots without row cover produced a total of 127.1 lbs. This farm reported selling a quart of African Eggplant (1 lb) for $5 in 2023. This 37.65 lbs yield increase with row cover translates to an $188.25 increase of revenue. Our single plot area was 37.5 ft2 and thus our row cover plot area was 75 ft2. This trial has demonstrated a potential $109335.60 / acre increase in African eggplant revenue by using row cover. Farmers qualitatively reported horticultural benefits to row cover as well. On 6/22/23, MAP farmer shared “there are so many more flowers on eggplants under row cover.” Project team members and MAP farmers noted darker green foliage on plants under row cover.

Lesson learned from this trial on best practices for using row cover include: regular weeding and drip irrigation are helpful for row cover success and using mulches can help; row cover may be most successful in areas where crops have not been previously grown for a few years or in areas that are known to be free of targeted pest.

MAP Farmer Katie reported the trial had numerous benefits for the farm’s social mission. She saw great value in the trial demonstration information sign (Figure 23) posted in front of the trial as a way to passively educators farm visitors exploring the farm. She shared hosting the trial was “fun and a great example for our community to see a field trial in action and be exposed to the process of agricultural research.” Katie estimates over 500 people interacted with the 2023 demonstration trial.

Releasing Ladybeetles to Manage Cabbage Whitefly

Overall, we found ample evidence that Delphastus predates on cabbage whitefly and reproduces successfully while doing so. However, it remains unclear how to effectively use Delphastus as a control for cabbage whitefly.

Detecting Parasitoid Wasp of Cabbage Whitefly

Rearing this Encarsia species demonstrated its ability to control cabbage whitefly in a controlled environment. A leading Encarsia taxonomist demonstrated that this is a previously undescribed species. The detection of a new pest parasitoid is a major output of the project and opens the door for further research such as habitat planting and other measures to encourage this endemic beneficial species.

Adjusting Soil pH to Manage Pillbugs

In this project, we demonstrated that pillbug feeding damage in high organic matter and high pH soils can be reduced by lowering soil pH with sulfur amendments, leading to increases in yield and revenue.

Taking a “Brassica Break” to Reduce Pest Pressure

Our approach to reduce brassica pest pressure was particularly successful. We observed consistently delayed and reduced overall pest pressure leading to increased crop quality and yields. The first year of the project we demo-trialed this practice on NYC seven farms. Due to early project success and results distribution to surrounding farms, at least ten NYC farms reported adopting this practice annually by the end of the project.

Resistant Cucumber Varieties for Downy Mildew

In side-by-side trials, resistant varieties substantially extended length of harvest time for cucumbers after appearance of cucurbit downy mildew.

Spotted Lanternfly Management

Our work suggested that yellow sticky tape may be effective as a low-cost barrier for keeping SLF nymphs off of trees; at least for fig trees, which have smooth bark that allows the tape to stay attached for several weeks. We struggled to successfully deploy this technique with other crop species.

Releasing Biocontrols and Other Tactics to Manage Aphids

Our work suggested releasing natural enemies can be successful in reducing aphid populations in enclosed systems such as greenhouses. Using a combination of lacewing larvae and adult aphid predatory midge with multiple releases reduced the aphid population on tomatoes and using adult lady beetles reduced the aphid population on winter greens, both demonstration trials took place in a greenhouse. We observed reduction in aphid population can lead to increased crop quality, length in harvest window, and reduction in pest management labor time. Lessons learned included it can be important to match up the life cycles of the natural enemy and their targeted pests. Additionally, it was observed other pest management products can harm natural enemies if not used properly.

Using insect exclusion netting to manage cucumber beetles

We demonstrated insect exclusion netting can be successful for managing cucumber beetle on squash and cucumber crops in caterpillar tunnels. Lessons learned include there can be unexpected impacts from implementing a management practice such as twospotted spider mite damage increasing and a need for parthenocarpic varieties.

Swede Midge Management

We identified swede midge as a problematic pest on urban farms in Rochester and Buffalo. In this project, we demonstrated to urban growers the usefulness of pheromone trapping to monitor swede midge populations throughout the season and how trapping helps us make and evaluate management decisions. Additionally, we demonstrated insect exclusion netting can increase collards yields, quality, and revenue, in growing areas that have not had brassicas in them for at least three years. In future work to manage SM, we are interested in looking at variety selection, ground barriers, and delaying planting as possible management tools. We are interested in researching the best way to assess damage on leafy greens and best time to remove insect exclusion netting.

Using Row Cover and Entomopathogenic Nematodes to Manage Flea Beetles

We demonstrated that row cover can increase yields and revenue for African eggplant and collards. Lesson learned from this trial on best practices for using row cover include: regular weeding and drip irrigation are helpful for row cover success and using mulches can help; row cover may be most successful in areas where crops have not been previously grown for a few years or in areas that are known to be free of targeted pest.

Education

This project had many pieces with a strong emphasis on education. Through regular scouting on farm visits and surveying growers on their pest management needs, we documented the most problematic pests and diseases for NYC, Buffalo and Rochester. Additionally, we documented current management practices, barriers to implementation and areas of future interest for urban growers in New York in a New York State Urban Growers Pest Management Needs Assessment. Project team members collectively conducted 380 farm visits and 304 off-farm consultations throughout the project.

Through on-farm demonstration trials, a total of 15 farms across NYC, Buffalo, and Rochester hosted demonstration trials that implement non-chemical pest management strategies such as host resistance, release of natural enemies, conservation biological control, pest exclusion, adjusting timing of planting, regular scouting and trapping. Farms were recruited through the relationships that project members have already established with growers. The on-farm trials provided growers the opportunity to observe the benefits of pest management practices first-hand and allowed us to document the impact of these management practices on urban farms with a focus on profitability, feasibility and yields.

We shared what we were learning with growers through workshops, farm tours, and written resources including newsletter articles and factsheets. In person and virtual workshops were held throughout the project to facilitate peer to peer learning. We hosted or participated in 39 workshops throughout the project for 71 hours of programming reaching 1077 participants, for a total of 76,467 contact hours. Workshops were predominantly held in NYC and Buffalo. Workshops concentrated on topics like pest identification, scouting, cultural, mechanical, and biological controls, and creating beneficial habitat for natural enemies.

The project team hosted three farm tours, one for growers and two for urban ag service providers. The grower farm tour exposed urban growers to rural vegetable production, pest management on a larger scale, scouting, common equipment used to manage pests, and preferred management practices. Shared learning on common issues created community building opportunities between urban and rural farmers, who were separated not only by geography, but also cultural and racial differences.

Results and events from this project were shared in over 30 newsletter articles and 60 social media posts estimated to reach over 7000 people. In the final year of the project, we developed a New York Urban Farms Sustainable Pest Management factsheet series with case studies highlighting pest management techniques from our demonstration trials. This factsheet series was created in place of the ‘Sustainable Pest Management Guide for NE Urban Agriculture’ initially proposed. Techniques featured include row covers, disease resistant crop varieties, biocontrols and taking a brassica break. To reduce barriers to accessing this knowledge, the urban farms sustainable pest management factsheets were translated into Spanish, Arabic, and Chinese (Mandarin). We chose these languages using a quantitative and subjective approach. To make this decision, we surveyed growers in our pest management needs assessment on what the top three languages they see for translation needs in their local urban agricultural community. Additionally, we looked at city school district language data and/or city language access plans for NYC, Buffalo, Syracuse, Rochester, Albany and Utica, and US Census Bureau American Community Survey data.

Milestones

1) Urban farmers in Buffalo and NYC agree to implement on-farm sustainable pest management trials such as crop rotation, pest exclusion, resistant varieties, release of beneficial insects, etc. Activity: Project team members utilize existing relationships with urban growers in Buffalo and NYC to recruit 15 sites suitable for on-farm pest management demonstration trials. Team members work with farmers to identify pest priorities and preferred management practices. We anticipate approximately 5 farms per project year to reach this milestone, and will report annually on this progress.

15

15

November 30, 2024

Completed

November 30, 2024

In the first year of the project, progress toward this milestone included the recruitment of 3 farms in Buffalo and 2 in NYC to implement on-farm sustainable pest management trials including as crop rotation, pest exclusion and the release of beneficial insects. In Buffalo, Swede Midge and Striped Cucumber Beetle were identified by growers as priority pests. In NYC, Twospotted Spider Mite and Cabbage Whitefly were major pests. Cabbage Whitefly in particular was of note as it is not a common pest in the Northeast, yet was the most prevalent pest on some NYC farms.

In the second year of the project, progress towards this milestone included the recruitment of two returning and four new farms in NYC and three returning and one new farm in Buffalo to implement on-farm sustainable pest management trials. In NYC, brassica pests including cabbage whitefly were identified as major pests, as well as pillbugs. Management tactics trialed this year included crop rotation, releasing biocontrols, and reducing soil pH. In Buffalo, aphids, Swede Midge and Cucumber Beetles were again identified by growers as priority pests. Management tactics trialed this year included releasing biocontrols, crop rotation, and using insect exclusion netting.

In the third year of the project, progress towards this milestone included the recruitment of four returning and one new farm in NYC, four returning and one new farm in Buffalo, and two new farms in Rochester to implement on-farm sustainable pest management trials. In NYC, cabbage whitefly, spotted lanternfly and cucurbit downy mildew were identified as major pests. Management tactics trialed this year included crop rotation, releasing biocontrols, physical barriers, and growing disease resistant varieties. In Buffalo, aphids, flea beetles and Swede Midge were identified by growers as priority pests. Management tactics trialed this year included releasing biocontrols, using crop covers, monitoring pest populations through trapping, and regular scouting. In Rochester, brassica pests such as Swede Midge were identified by growers as priority pests. Management tactics trialed this year included monitoring pest populations through trapping and regular scouting.

In the final year of the project, progress towards this milestone included the recruitment of two returning farms in NYC and one returning farm in Rochester to implement on-farm sustainable pest management trials. In NYC, twospotted spider mite and cucurbit downy mildew were identified as major pests. Management tactics trialed this year included crop rotation, growing disease resistant varieties, and conservation biocontrol. In Rochester, swede midge was identified growers as a priority pest. Management tactics trialed this year included monitoring pest populations through trapping and regular scouting and using insect exclusion netting.

2) Urban farms across cities in NYS (Albany, Rochester, Buffalo, Troy, Binghamton, Syracuse, NYC, etc.) complete survey on the predominate pest issues, preferred pest management practices, perceived benefits, resources and information needed, etc. Activity: Project members craft survey and submit to 75 urban farms across NYS.

50

43

March 01, 2022

Completed

April 08, 2024

A survey was created in print and online form in Fall 2022. It was distributed on four relevant program websites, two newsletters, four list servs, over six social media accounts, and at one urban ag conference estimating to reach over 4,300 people. In Fall 2023, we reached out to educators directly working with urban agriculture communities that project team members are not closely associated with including Batavia, Syracuse, Skaneateles, Utica and Binghamton for support in survey distribution. Our target audience for the survey was urban growers (farmers and gardeners). We defined “urban” growers using the USDA definition of urban - as people growing in areas located in/near urbanized areas (have a population of 50,000 or more) or in/near urban clusters (have a population between 2,500 and 50,000). Project team members had success asking growers survey questions directly and recording responses. This led to informative conversations helping to shape the direction of this project. Our original proposed completion date was 3/1/2022 and this was not met due to team personnel changes. We achieved this milestone and closed the survey on 4/8/24.

Results of this survey were shared in the publication New York State Urban Growers Pest Management Needs Assessment. This needs assessment was shared on three websites- CCE Cornell Vegetable Program Pests page ; CCE Harvest New York Urban Agriculture page ; and the New York Farm Viability Institute Farmer’s Research Needs page , four newsletters and shared on five urban agriculture list servs across the state estimating to reach over 7000 people.

3) Urban farmers/managers/youth interns are exposed to rural vegetable production and pest management. They learn about the predominate pests in rural settings. Rural farmers learn from urban growers about their challenges in managing pests and provide advice on how pest controls could be adapted to urban settings. Activity: Urban farmers tour rural vegetable farms outside Western NY or NYC.

30

30

October 31, 2023

Completed

Through collaboration with Mid-Hudson Collaborative Regional Alliance for Farmer Training (CRAFT), a group of 30 NYC urban farmers and students toured Choy Division Farm on 9/29/22 (Figures 24 and 25). The group learned from farmer, Christina Chan, an urban farmer who left the city to pursue her farm dream. Choy Division is a small vegetable farm located outside of NYC that is focused on growing East Asian heritage crops using regenerative agricultural techniques.

4) Service providers (CCE Educators, NRCS staff, other support agencies) gain knowledge on pest management practices that are effective on urban farms. Activity: service providers attend regional and statewide workshops, project staff meet with service providers one-on-one, service providers read online posts with project data, attend demonstration workshops at host farms.

15

20

15

187

November 30, 2024

Completed

November 30, 2024

In 2022, one statewide in-person workshop was held on “Unique Pest Challenges in Urban Agriculture” at the CCE Agriculture, Food & Environmental Systems In-service conference. This conference is geared towards CCE educators, industry professionals and Cornell faculty to discuss latest developments in research and practice. Our workshop shared updates on the year’s top pests and management strategies on urban farms in NYC, Buffalo, and other cities across the state.

In 2023, two statewide in-person workshops were held at the CCE Agriculture, Food & Environmental Systems In-service conference. Workshops shared updates on spotted lanternfly research and best practices for conservation biocontrol on urban farms. Additionally, a group of 20 service providers toured Massachusetts Avenue Project urban farm in Fall 2023 observing the flea beetle pest management demonstration trial and discussing pest management practices that are effective on urban farms (Figure 26).

In 2024, project updates were shared with urban ag service providers at the Urban Food Systems Symposium in Columbus Ohio (Figure 27) and the at the CCE Agriculture, Food & Environmental Systems In-service conference. Additionally, in October 2024, Harvest New York’s NYC team hosted urban agriculture leaders from the United States Department of Agriculture’s Farm Service Agency and Natural Resources Conservation Service, and extension members of the National Urban Agriculture Initiative (Virginia State University, Virginia Tech, Cornell University, Tulane University) to discuss urban agriculture opportunities and challenges in New York. Farmers from Brooklyn Grange, GrowNYC, Oko Farms, and New Roots, from Brooklyn, Manhattan, and the Bronx, participated in the discussion and hosted tours of their spaces. The project team specifically discussed production practices at each farm location and hosted discussion between USDA and land grant staff with farmers to discuss solutions to local challenges including pest management and soil maintenance.

5) NYS urban farm managers, adult employees, and youth learn about sustainable pest management. They will improve their identification skills of pests that are frequently problems on urban farms. They will learn how to scout for pests, understand the concept of thresholds, and gain confidence in their ability to accurately identify pests. Activity: Farmers attend regional and statewide workshops/conferences, participate in on-farm discussions, and attend on-farm workshops.

150

4

890

187

February 29, 2024

Completed

November 30, 2024

Four events were held in 2021, 3 virtual and 1 in-person, reaching a total of 87 participants. The curriculum for these events was largely focused on beneficial insects; how to attract, rear, and create habitat for them. The pests of concern were aphids, Twospotted Spider Mite and Cabbage Whitefly.

Nine events were held in 2022, 4 virtual and 5 in-person, reaching a total of 181 participants. Workshops covered topics including scouting and pest identification, understanding life cycles of important pests and how to manage them, understanding beneficial insects, and using organic and biopesticides. Three workshops were targeted specifically towards youth, with a focus on insects on the farm, building healthy soils, and cultivating healthy land and community.

Thirteen events were held in 2023, 2 virtual and 11 in-person, reaching a total of 276 participants. Workshops covered topics including scouting and pest identification, understanding life cycles of important pests and how to manage them, understanding beneficial insects, and using organic and biopesticides. Four workshops were targeted specifically towards youth, with a focus on IPM on urban farms, scouting and pest management.

Twelve in person events were held in 2024 reaching a total of 533 participants. Workshops covered topics including spotted lanternfly management, and understanding life cycles of important pests and beneficial insects and how to manage them. Three workshops were targeted specifically towards youth, with a focus on IPM on urban farms, scouting and pest management.

A highlight in 2024 included the project team hosted an Urban and Small-Scale Grower Meeting in Buffalo on 4/5/24 reaching over 60 urban farmers and agriculture service providers from across western and central New York. Meeting workshop topics ranged from pest management to tree fruit production to improving okra earliness and yield. This event featured a “How We Manage Insects on our Farms” growers panel featuring three of our collaborating farmers sharing best practices for pest management using techniques such as row covers, biocontrols, and choosing disease resistant varieties (Figure 28). This event created a space for urban farmers from Buffalo, Rochester, and Syracuse to build community, engage in production-focused workshops, and share resources. Event feedback was overwhelmingly positive. Attendee comments on something they are taking away from this event in a post survey included “more confidence in managing pests and diseases”, “being in community with other growers and ag professionals makes learning more fun”, “connecting with helpful people and resources”, “new techniques for pest and soil management and networking with other growers”, and “the power of collaboration and community.” Over 15 topics were suggested to cover in future events.

In total, our project included 39 workshops for 71 hours of programming reaching 1077 participants.

|

Date |

Duration (H) |

Attendance |

Delivery |

Title |

|

3/26/2021 |

2 |

14 |

Virtual |

Intro to IPM for Urban Vegetable Growers |

|

3/30/2021 |

2 |

12 |

In-person |

Pest Management for Urban Farmers |

|

5/4/2021 |

1.5 |

44 |

Virtual |

Recognizing and attracting natural enemies to urban farms and gardens |

|

9/30/2021 |

1 |

17 |

Virtual |

Basic Insect Rearing for Urban Ag IPM |

|

1/24/2022 |

3 |

56 |

Virtual |

Urban Farmer-to-Farmer Summit |

|

3/3/2022 |

1.25 |

19 |

Virtual |

Urban Ag Pest Updates: Twospotted Spider Mite |

|

3/9/2022 |

1.25 |

17 |

Virtual |

Urban Ag Pest Updates: Cabbage Whitefly |

|

5/10/2022 |

1 |

12 |

Virtual |

Minimized Pest Control Risks on the Urban Farm |

|

7/28/2022 |

1 |

10 |

In-person |

Insects: Beneficials and Pests |

|

8/4/2022 |

1 |

10 |

In-person |

Composting and Healthy Soils |

|

8/11/2022 |

1 |

12 |

In-person |

Cultivating Healthy Land and Community |

|

8/18/2022 |

2.5 |

7 |

In-person |

Organic Pesticide Discussion and Demo |

|

9/29/2022 |

3 |

30 |

In-person |

CRAFT NYC Rural Farm Tour |

|

11/18/2022 |

1.5 |

8 |

In-person |

Unique Pest Challenges in Urban Agriculture |

|

2/23/2023 |

1 |

36 |

Virtual |

Conserving friendly insects on urban farms and gardens |

|

3/7/2023 |

1.25 |

15 |

Virtual |

NYC Vegetable Pests & Diseases: 2023's Most Wanted |

|

6/9/2023 |

2 |

8 |

In-person |

South Lawn Farm Workforce Development Scouting Workshop |

|

7/8/2023 |

2 |

20 |

In-person |

Integrated Pest Management workshop |

|

7/26/2023 |

2 |

12 |

In-person |

IPM on the Urban Farm |

|

8/2/2023 |

2 |

12 |

In-person |

IPM on the Urban Farm |

|

8/3/2023 |

2 |

21 |

In-person |

Biological Besties - A Cornell IPM Skillshare Event |

|

8/9/2023 |

1 |

18 |

In-person |

Pest scouting workshop |

|

8/9/2023 |

2 |

12 |

In-person |

IPM on the Urban Farm |

|

10/3/2023 |

2 |

20 |

In-person |

Urban Ag Pest Management Needs Service Providers Tour |

|

10/12/2023 |

3 |

22 |

In-person |

Plant Health Care and Urban IPM |

|

11/7/2023 |

1.5 |

45 |

In-person |

Spotted Lanternfly Update |

|

11/8/2023 |

1.5 |

35 |

In-person |

Conservation Biocontrol |

|

1/19/2024 |

3 |

65 |

In-person |

Urban Farmer-to-Farmer Summit |

|

2/15/2024 |

1.5 |

17 |

In-person |

Spotted Lanternfly Management |

|

3/9/2024 |

1 |

200 |

In-person |

Bugs of Note: Insect Friends and Foes |

|

4/5/2024 |

6 |

63 |

In-person |

Urban and Small Scale Grower Meeting |

|

6/11/2024 |

0.5 |

30 |

In-person |

Sustainable Pest Management for New York Urban Farmers (Urban Food Systems Symposium) |

|

7/24/2024 |

2 |

12 |

In-person |

IPM on the Urban Farm |

|

7/31/2024 |

2 |

12 |

In-person |

IPM on the Urban Farm |

|

8/7/2024 |

2 |

12 |

In-person |

IPM on the Urban Farm |

|

8/10/2024 |

1 |

23 |

In-person |

Urban Ag IPM (Resilient Gardens Symposium) |

|

10/7/2024 |

4 |

24 |

In-person |

USDA CCE NYC Urban Ag Tour |

|

10/24/2024 |

1 |

50 |

In-person |

Sustainable Pest Management for New York Urban Farmers |

|

11/19/2024 |

0.5 |

25 |

In-person |

CCE Urban Agriculture Project Updates |

|

Totals |

71 |

1077 |

39 events in total |

6) 100 Sustainable recommendations from service providers (CCE Educators, NRCS staff, other support agencies) to farmers on disease resistant varieties, crop rotation, purchasing and releasing biological controls, insect/disease identification, and so on. Activity: Service providers meet with farmers, consult with project staff, provide follow up visits to farms to verify successful implementation, provide data to project staff.

25

20

33

October 31, 2023

Completed

November 30, 2024

Routine scouting on urban farm visits was done by project team members across New York State throughout the project. In 2023, we conducted an intentional urban farm scouting program with seven farms in Buffalo and two farms in Rochester. A project team member visited each farm on a regular basis three to ten times throughout the growing season making note of crop health, pests and diseases observed. This information was shared with farmers as well as management recommendations. Some of these farms host summer youth and young adult employment programs. Occasionally, the young adults would participate in scouting. After participating in a scouting session, CCE Monroe South Lawn Farm Manager Mike shared “wow I am out here every day and have noticed more things in this last hour than my entire time on the farm. I understand now why it is important to monitor the crops.” The scouting program continued in 2024 including three farms in Rochester and five farms in Buffalo.

7) Northeast urban farm managers, adult employees, and youth will be exposed to sustainable pest management on urban farms and the corresponding economic and environmental benefits via on-line publications (VegEdge, Harvest NY newsletter), social media posts, email consultation, phone consultation, or on-farm visits.

500

20

8270

187

February 29, 2024

Completed

November 30, 2024

Results and events from this project were shared in 20 articles in the Cornell Vegetable Program newsletter “VegEdge”, 17 articles in the Harvest NY Urban Agriculture newsletter “NYC Market Growers Update”, and in over 60 social media posts on team social media. The project team conducted 380 farm visits and 304 off-farm consultations (phone and email).

In the final year of the project, we developed a New York Urban Farms Sustainable Pest Management factsheet series with case studies highlighting pest management techniques from our demonstration trials. Techniques featured include row covers, disease resistant crop varieties, biocontrols and taking a brassica break. The factsheet series was shared on two websites- CCE Cornell Vegetable Program Pests page and CCE Harvest New York Urban Agriculture page , four newsletters and shared on five urban agriculture list servs across the state estimating to reach over 7000 people.

Milestone activities and participation summary

Educational activities:

Participation summary:

Learning Outcomes

We assessed learning outcomes through routine farm visits, grower interviews, uniform survey tools and evaluations at workshops and farm visits. At the end of the project, we surveyed 15 urban growers that engaged in demonstration trials and project educational activities using a uniform survey tool. Results from the final grower evaluation are below:

- 14/15 growers reported their ability to identify pests and diseases affecting their farm has increased as a result of this project.

- 14/15 growers reported they learned new management strategies or increased understanding of management strategies as a result of this project.

- 13/15 growers reported they implemented sustainable pest management strategies on their farm as a result of this project.

- 10/15 growers reported implementing these sustainable pest management strategies increased profitability through increased yield.

- 9/15 growers reported implementing these sustainable pest management strategies increased profitability through increased produce quality.