Final report for LS20-332

Project Information

A silvopasture system involves intentionally integrating trees, shrubs and livestock on the same land. To date, these systems have largely been designed for ruminant livestock, such as cattle. However, novel silvopastures are being developed for poultry because these systems have potential to provide high quality habitat and feed sources that may improve bird health and welfare. The purpose of this project is to develop and assess sustainable poultry-based silvopastures. The research team combines expertise in broiler welfare (PI) and silvopasture production (co-PIs), plus large and small-scale poultry farmers as collaborators. Applying a systems-approach, we will assess animal welfare, economic, and environmental outcomes when integrating poultry production with novel silvopastures.

To meet certification requirements, organic chicken producers have to provide outdoor access. These ranges are grass pastures, yet chickens prefer overhead cover and shelter in their outdoor range. This habitat preference may be realized through the implementation of silvopastures. Using a novel silvopasture system could increase land-productivity through additional income from vegetation and reduced feed costs. Chickens may benefit from natural cover and increased range use, which is often limited. In turn it can lead to improved leg and feet health, diet diversity, and improved meat quality. Silvopastures would also improve animal comfort as the vegetation moderates understory microclimate. Environmental benefits could include improved soil quality, air quality, and biodiversity, which in turn can improve societal acceptance of poultry production. Although silvopasture systems offer many potential benefits, they have received little study in a poultry context, and even less extension and outreach effort. The project will contribute knowledge for family farm poultry systems, both on a large and small-scale, to provide information on how to improve profitability and stability.

This proposal is directed to poultry-centered silvopasture production systems. With this project, we aim to move existing organic poultry production systems toward more sustainable agriculture, in which animal welfare, economics, and the environment are balanced, and we want to strengthen awareness of existing silvopasture-based poultry production systems by collecting case studies that provide success stories and resources on how to overcome challenges. We will assess animal welfare, economic, and environmental parameters of combining silvopasture with poultry production by fulfilling three objectives:

Year 1:

- Experimental trial: Compare broiler chicken production with access to existing silvopastures to broiler production with access to grass pasture, at the VT Shenandoah Valley AREC, focusing on:

- Animal welfare: behavior, fear, leg and feet health

- Economics: animal yield and theoretical land yield

- Environment: biodiversity and soil parameters

Year 1-3:

- Field trial:

- (A) Compare broiler chicken production with access to a newly planted silvopasture on a large-scale commercial USDA Organic farm to grass pasture access on the same farm

- (B) Compare broiler chicken production with access to established silvopastures on two small-scale commercial farms to grass pasture access on the same farms, focusing on:

- Animal welfare: behavior, fear, leg and feet health

- Economics: animal yield and theoretical land yield

- Environment: biodiversity and soil parameters

- Increase adoption of poultry-based silvopasture practices by:

- (A) Surveying silvopasture- and traditional-system poultry producers about their experiences, concerns and opportunities for applying these practices

- (B) Creating and disseminating case studies from above-mentioned and other established silvopasture producers through extension

- (C) Showcasing poultry silvopastures through research center and on-farm field days and web-based delivery tools

- (D) Disseminating technical and budget information to producer and agency communities.

For objective 1 and 2, the same measures will be collected at four different sites: (1) the Virginia Tech Shenandoah Valley AREC, (2) a USDA Organic large-scale farm where we will plant a new silvopasture, (3 and 4) two small-scale broiler farms with established silvopastures. At all sites, we aim to compare measures in flocks with and without access to silvopastures (meaning grass range versus silvopasture range). Objective 3 is aimed at educating industry stakeholders and promoting the system’s benefits.

Cooperators

- - Producer

- - Technical Advisor (Educator and Researcher)

- - Technical Advisor

- - Technical Advisor

- - Technical Advisor - Producer

- - Technical Advisor - Producer

Research

Our combined ‘research and extension approach’ includes a controlled experimental design (objective 1) comparing silvopasture access to grass pasture access for small flocks of broilers, executed at the Shenandoah Valley Agricultural Research and Extension Center (AREC). For objective 2, we will perform a field trial with a similar approach as objective 1, but applied at commercial farms. On each of the site (with possible exception of Wil Crombie’s farm), we will have a silvopasture-flock and a grass pasture-flock serving as a control to compare specific parameters related to welfare, economics and environment.

At the end of this study, an extension report will illustrate all these potential benefits and will contain photos and input from new and experienced silvopasture/broiler chicken producers than can serve as an educational document for industry stakeholders. Two field days will provide additional information on feasibility of the integrated system for interested parties and educate industry stakeholders on the system possibilities (objective 3).

Year 1 Objective 1 - Experimental trial: Compare broiler chicken production with access to existing silvopastures to broiler production with access to grass pasture, at the VT Shenandoah Valley AREC

Two experiments were conducted from April to May (Experiment 1; Exp 1) and June to August 2021 (Experiment 2; Exp 2). All procedures were approved by the Virginia Tech Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC protocol 20-044).

Animals and housing

In total, 886-day-old Ross 708 mixed-sex chicks in Exp 1 and 648 chicks in Exp 2 were obtained from a commercial hatchery (Harrisonburg, VA, USA). Birds were Marek’s vaccinated at the hatchery. Upon arrival, chicks were arbitrarily selected and housed in 12 identical pens (5.7 m2) with 73 or 74 birds per pen in Exp 1 and 53 or 54 birds per pen in Exp 2. Pens contained pine wood shavings (~5 cm depth), a heat lamp (day 1-8), a cardboard feed flat with feed (day 1-8), one bell drinkers (Plasson® Broiler Drinker complete, Or-Akiva, Israel), and one pet champion poultry drinker (Stout Stuff LLC, made in china), and one feeder (Superbowl poultry feeder, LaGrange, NC, USA). The chicks were fed commercial starter (day 0-15), grower (day 15-25), and finisher (day 25-42 or 43) diets meeting NCC recommendations (National Chicken Council 2017). Ambient temperatures were 35°C on day 1 and gradually reduced to 23°C on day 22 (Exp 1) or day 23 (Exp 2). Lighting was provided continuously for the first week and reduced to 12h light and 12h dark until day 22 (Exp 1) or day 23 (Exp 2).

In Exp 1, birds from each pen were equally but randomly allocated over 16 pasture-based treatments resulting in 53 birds per plot originating from all 12 pens. In Exp 2, complete pens (53-54 birds) were randomly allocated to 12 pasture-based plots with chicken coops. On day 22 (Exp 1) or day 23 (Exp 2), birds were transported for 1.5h to the pasture-based experimental site located at the Shenandoah Valley Agricultural Research and Extension Center (AREC) in Raphine, VA, USA. After transportation, birds were kept inside the coops for two days in Exp 1 and one day in Exp 2 to get acclimated to their new housing conditions. From days 24-41 or 42, coop doors in each plot were opened at approximately 8:00 am and closed at approximately 5:00 pm.

All pasture-based plots (125m2, 16 in Exp 1, and 12 in Exp 2) contained a chicken coop (6.55m2) constructed from wood, chicken wire, and tarp . The coops contained a wooded platform perch (0.05m x 0.1 m x 2.4 m) and the same feeder and bell drinker as when housed indoors. Coops were moved laterally across the plot each week. Plots were fenced with 1m-high and 50-meter-long FlexNet electric fences (PoultryNet®, Washington, IA, USA), connected to a 30-volt electric cattle fence.

Treatments

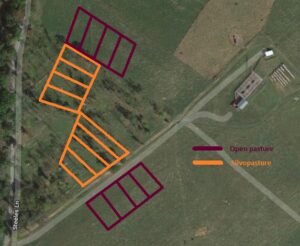

The silvopasture plots (8 replicates in two locations in Exp 1 and 6 replicates in two locations in Exp 2; Figure 1) contained a 10-12-year-old mixed hardwood stand of black walnut (Juglans nigrea L.) and hickory (Carya spp. Nutt.) trees and 30 newly planted saplings per plot (American hazelnut (Corylus americana), black walnut (Juglans nigra), persimmon (Diospyros virginiana L.), southern red oak (Quercus falcata Michx.), and southern pine (Pinus spp.) of approximately 30 cm height and 1 cm calipers. Saplings were planted in six rows with inter and intra-row spacing of 1.5 m. Canopy cover in all silvopasture and open pasture plots were calculated from photos using ImageJ software (1.5.3k, National Institute of Health, USA). The images were taken at ground-level in the center of the plot straight upwards. Photos were converted to 8-bit, binarized, and then the number of black (canopy) and white (sky) pixels were calculated as a percentage of total pixels. The canopy cover for silvopasture plots was (mean ± standard deviation) 31.7 ± 16.7% in Exp 1, and 33.3 ± 10.9% in Exp 2.

The open pasture plots (8 replicates in two locations in Exp 1 and 6 replicates in two locations in Exp 2; Figure 1) contained ground vegetation. Ground vegetation in the open pasture and silvopasture plots were similar and consisted of tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea Schreb.), orchardgrass (Dactylis glomerata L.), honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica Thunb.), greenbrier (Smilax spp. L.), Virginia creepers (Parthenocissus quinquefolia L. Planch.), horsenettle (Solanum carolinese L.), common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca L.), and thistle (Sonchus spp. L.). Canopy cover in open pasture plots was 0 ± 0% in Exp 1 and Exp 2.

Experimental setup for objective 1 at the VT AREC. The orange rectangles indicate 8 silvopasture plots that will hold 50 broilers each. The maroon rectangles indicate the 8 grass plots that will hold 50 birds each.

Data will be collected, focusing on aspects of animal welfare, economics and environment.

Animal welfare. Range use may benefit leg health, footpad health and fearfulness. For all sixteen 50-bird flocks, range use will be assessed via two approaches; cameras (e.g. Bushnell Trophy Cam) and live observations. One photograph per hour will be taken within the chicken coop and used to calculate the percentage of birds outdoors each hour. Hourly live observations will be performed at plot level to count birds in the range between 8 AM and 5 PM on days 29, 30, 34, 35, 40, and 41. The observer will sit down 5 m from the plot to prevent changes in the birds’ behavior. The percentage of birds near, middle, and far from the coop, and the total percentage of the flock in the range were calculated.

Assessment of how the management systems affect bird fearfulness will be determined with a Tonic Immobility test. The test consists of placing a chicken on its back in a U-shaped cradle and restraining it for 15 sec (Stadig et al. 2017). The chicken is then released and the time until righting (latency) is recorded, with longer durations of tonic immobility associated with greater fear. The test will be performed in week 5, after birds have had sufficient time to adopt to their respective environments, and 10 birds per coop will be assessed.

On the following day, leg condition will be assessed via a latency-to-lie test, in which birds are placed in a tote with a small amount of water. The time (latency) until the birds sit down will be recorded as an indicator of leg health or strength. In addition, footpad dermatitis and hock burns will be scored on a 0-4 categorical scale, with increasing scores indicative of worse lesions (Welfare Quality® Network 2009).

Economics. Economic productivity of the poultry system will be assessed by measuring animal growth (coop-level n = 50 per coop), feed conversion (coop-level, n = 8 per treatment) and whole-carcass yield (individual level n = 10 per coop). Feed intake will be recorded per group, starting from day 1 by weighing provided and left-over feed (difference = consumed feed). All birds will be weighed prior to processing on day 42 and carcass weights will be recorded thereafter for a sample of 10 birds per coop.

Environment. Temperature and humidity will be monitored in the range and within the coops using temperature-humidity sensors. We will assess soil quality on each plot twice to assess potential benefits from silvopasture/broiler production integration for the environment. Outdoor range soil quality will be assessed at three locations in each range (n = 16). To determine soil chemical properties, samples will be systematically collected at four distances from the coop (close, middle, end of range), resulting in 4 samples per flock per sampling time (baseline or post-experiment; total sample n(16*4*2)=128). At each location the surface litter will be removed and a sample collected with bucket soil augur. All samples will be homogenized separately by depth in a bucket onsite to obtain a single 50-g sample for each depth. Samples will be air dried and sieved with a 2-mm soil sieve. Soil sample analyses will be done to assess C and N, soil microbial biomass carbon (MBC), microbial biomass nitrogen (MBN), C and N fractions, and phospholipid fatty acid content (PLFA). The latter is used as a biological indicator of overall soil quality (Quideau et al. 2016).

We propose to quantify insect diversity using a combination of direct observations, pitfall traps and sticky cards. Flowering plants will be observed directly to assess the quantity and diversity of pollinators, which will be grouped into the following categories: lepidoptera (butterflies), bumblebees, honeybees, other native bees, hoverflies, and wasps. Sticky cards will be used to assess flying insects, especially lady beetles. Pitfall traps will be used to assess ground beetles and orthoptera (especially crickets). We expect insect abundance and diversity to be greater in complex habitats with trees and native grasses than in conventional grass pastures.

JACOBS and GRAD STUDENT will be responsible for animal measures and soil collection with the technician, PENT will be responsible for silvopasture related measures, the environmental measures will be coordinated by JACOBS and soil samples will be analyzed through the South Dakota State University Soil Analysis Service Lab led by Dr. Sandeep Kumar (please see the letter of commitment for this contractual service here: Letter of Commitment SD STATE).

Year 1-3 Objective 2A - Field trial: Compare broiler chicken production with access to a newly planted silvopasture on a large-scale commercial farm to grass pasture access on the same farm

Our cooperating large-scale VA-based poultry producer (SVO farmer Pam Miller) operates 3 commercial broiler chicken houses for approx. 90,000 birds. Each of the houses used in their system has pop holes along its length; these holes provide birds with access to grass pasture. On one of these three pastures we will establish a new silvopasture incorporating woody species and native grasses. Targeted woody species include Red Mulberry (Morus rubra), hazelnuts, pawpaw, and serviceberry. These species grow fairly rapidly and can provide shrubby cover and long-term feed resources. In addition to shrub cover, we will plant switchgrass (a native warm-season species) using sprigs (rather than seed) to generate rapid cover. Switchgrass is of interest given its potential to trap and reduce dust, to store carbon in deep root systems, and to serve as a source of bedding material or heating fuel for poultry operations.

The silvopasture system with trees, shrubs and grasses will be planted in rows parallel to the length of the house. The row-planting and space in between grasses, trees and shrubs (within rows) will allow for birds to move freely throughout the pasture. We will work with the landowners to design and install a mix of woody species and switchgrass based on their preference of vegetation and the physical layout of the space. The flocks with access to this newly established silvopasture plot will be compared to a control flock in one of the two adjacent houses.

For three production rounds spread over two years, we will collect data on animal welfare parameters (described for objective 1: fearfulness, leg health, footpad dermatitis and hock burns) in a sample of 80 birds per flock (two flocks per round) at week 5 of age. In addition, farmer and processing plant records will provide information on mortality, animal yield and carcass rejections. Litter moisture and soil quality data (6 samples per treatment (2), per round (3) = 72 soil samples total) will be assessed as described for objective 1.

Year 1-3 Objective 2B - Field trial: Compare broiler chicken production with access to established silvopastures on two small-scale commercial farms to grass pasture access on the same farms

Similar to objective 2a, animal welfare, economic and environmental parameters will be assessed on two small-scale broiler operations (VA and MN). At these sites, producers already have integrated chicken production with silvopastures, or they have trees and shrubs as part of the outdoor range for broilers. The setup on the VA farm (small-scale producer Brent Wills) will be similar to the large-scale farm in that two flocks will be simultaneously grown, one with and one without access to shrubs and trees in their outdoor range (pasture versus silvopasture). All their birds have access to an outdoor range when temperatures allow. Broilers have full access to pasture and/or woods at all times once they come out of the brooder, usually at 2-3 weeks old, depending on time of year and weather. They grow a commercial hybrid breed (Freedom Rangers). All of their pastures border woods and fringe areas, so the birds have access to woods, trees and shrubby type vegetation, typically oak, hickory, maple, sourwood, pine thickets and the associated brambles and brushy vegetation. Their flock sizes depend on demand. Their pens allow for 80 birds per pen. They use Salatin-style pasture pens that offer 120 sf of “indoor” space per pen (10’x12’) as well as an A-frame pen with the same floor dimensions. For this study we will collect data during three rounds of production, with birds either with access to pasture (conventional outdoor range), or to vegetation (silvopasture).

On the MN farm (small-scale producer Wil Crombie), they grow birds according to the Regeneration Farms system/design for 5 years now. They have 40 acres and planted 20,000 hazelnut shrubs, around 5,000 elderberry bushes and a few thousand tree species, including oak, sugar maple, chestnut, basswood and Honey Locust. They currently have two active chicken barns. Their birds have outdoor access to grasses, Comfrey, Hazelnut and Sugar maple leaves and other naturally occurring plant species that are inside the paddocks. They also sprout grains within the paddocks. A single flock consists of 1,500 birds and is housed in a steel structure barn (18'x90'). The birds have outdoor access to circa 1.5 acres. At this point, we are not sure yet whether we can simultaneously assess birds with and without vegetation access as on the other farms and at the AREC.

For both farms, measurement include fearfulness, leg health, footpad dermatitis, hock burns on 80 birds per flock (n = 2 per farm, per round), assessed a week prior to processing. In addition, farmer and processing records will provide information on mortality and animal yield. Litter moisture and soil quality (6 samples per treatment (2), per round (3) = 72 soil samples total per farm) will be assessed as described for objective 1.

JACOBS and GRAD STUDENT will be responsible for animal measures, and collection of soil samples together with the technician, FIKE and MUNSELL will be responsible for silvopasture related measures. The environmental measures will be supervised by JACOBS and soil samples will be analyzed through the South Dakota State University Soil Analysis Service Lab lead by Dr. Sandeep Kumar.

Year 1-3 Objective 3: Increase adoption of poultry-based silvopasture practices

3A. Surveying silvopasture- and traditional-system poultry producers about their experiences, concerns and opportunities for applying these practices

Online search plus network search of southeastern US-based small and large scale silvopasture producers in combination with poultry. In addition, the director of the American Pastured Poultry Producers Association (APPPA) is willing to assist in the search for volunteers for the interviews among their members. We aim to perform at least six quantitative in-depth interviews in person, over the phone, or via email depending on geographical location and producer preference. Questions will relate to productivity, animal welfare, and environment. Additionally, we will ask about particular challenges and how they were overcome, including potential exposure to predators. We will collect photo material for the extension publication; a case-study report (b) (online and hard copies). Role of farmers: partake in interviews, allow or provide photos at/from farms. GRAD STUDENT will interview, perform farm visits, supervised by JACOBS.

3B. Creating and disseminating case studies from abovementioned and other established silvopasture producers through extension

Outcomes from interviews and farm visits will be structured and organized into an extension publication with photos and text. JACOBS will coordinate, GRAD STUDENT will write, collate, and disseminate (online and hard copies). MUNSELL, DOWNING, PENT and FIKE will advise on extension documents. Consultants and farmers will be involved with development and dissemination.

3C. Showcasing poultry silvopastures through research center and on-farm field days and web-based delivery tools

Two field days will be organized during which interested stakeholders are welcomed to visit at least one of the participating farms. The large-scale farmer already indicated willingness to assist with this field day and allow for visitors. The Shenandoah Valley AREC will be the location of a second field day for interested parties. These days will provide interested parties to see and experience a silvopasture approach and ask questions about this system. Some research outcomes will be presented to attendees for education purposes. Role of farmer: allow access to farm and talk about experiences. JACOBS will coordinate, FIKE and PENT will lead actual field days.

3D. Disseminating technical and budget information to producer and agency communities

Based on data collected for objective 1 and 2, we will be able to formulate some poultry-silvopasture system scenarios and calculate associated budgets for those scenarios. These will be disseminated as technical information with targeted audience being industry stakeholders. MUNSELL and DOWNING will coordinate silvopasture aspects of the technical and budget outcomes, JACOBS will coordinate animal-related aspects. Consultants and farmers will be involved with development and dissemination.

For objective 1 and 2, we will repeatedly assess the same measures at four different sites: (1) the Shenandoah Valley AREC, (2) a large-scale farm where we will plant a new silvopasture, (3) and (4) two small-scale broiler farms with established silvopastures. At all sites, we aim to compare measures in flocks with and without access to silvopastures (meaning grass range versus silvopasture range). This results in flocks as the experimental unit, with at (1) 16 flocks (8 with and 8 without silvopasture access), (2) 6 large-scale flocks (3 with and 3 without silvopasture access), (3) 6 small-scale flocks (3 with and 3 without silvopasture access), and (4) 3 small-scale flocks with silvopasture access. The commercial farms differ in farm size (small-scale versus large-scale), “age” of silvopasture system (newly established (year 0) versus well-established (~year 5)), and flock access to vegetation within a farm (flocks either have access to grass pasture or access to silvopasture). The first factor will illustrate the feasibility of integration vegetation production and broiler chicken production on a large scale compared to a smaller scale farm. The well-established silvopasture systems will be on small-scale farms, as the approach has not yet been used by large poultry producers. Our approach, in which we will plant a silvopasture system on a large farm, will provide insight regarding benefits associated with new silvopasture systems. The established systems (small-scale farms and the experimental trial from objective 1) will serve as “proof of concept” for a more commercial application, and will illustrate potential benefits on a longer term. Thus, the large-scale production system will illustrate the potential benefits on the short term, and the small-scale farms benefits on the long term.

We have faced challenges due to the pandemic, that in part resulted in a delay in the research activities. A new challenge has arisen in 2021 with the spread of highly pathogenic avian influenza across the U.S., limiting farm access.

Objective 1 - Experimental trial: Compare broiler chicken production with access to existing silvopastures to broiler production with access to grass pasture, at the VT Shenandoah Valley AREC

We managed to successfully complete two replicates (Experiment 1 and Experiment 2), rather than one, of the experimental trial with the support of the Young Scholar Enhancement Grant Award.

Animal welfare

Range use

Photos: Plot-level range use was assessed hourly from photos for 5 plots per treatment in both Experiment 1 and Experiment 2 using wildlife cameras (HC400 trail camera, Victure, Guangdong, China). Photos were taken between 8 AM and 5 PM from days 26-41 in Experiment 1 and day 24-41 in Experiment 2, resulting in a sample of 772-803 usable photos per treatment in Experiment 1 and 890-899 photos per treatment in Experiment 2. Cameras were mounted on poles at approximately 2-m height and placed at approximately 9 m from the plot. Ranging distance was categorized as near the coop, middle of the range, and far from the coop using stake flags at each threshold to be able to determine the distance. The total proportion (%) of the flock in the range, and the proportion of the flock at each distance were calculated (Table 1). The number of birds were counted using ImageJ software (1.5.3k, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). The ‘multi-point’ tool was used for counts by ranging distance (close, middle, far). In Experiment 1, vegetation could conceal birds that were ranging in the plot. Therefore, we were only able to determine the minimal count of birds in the range. In Experiment 2, ground vegetation in both treatments was mowed prior to bird placement.

Live observations: In Experiment 2, hourly live observations were performed at plot-level for all plots (6 per treatment) to count the number of birds in the range between 8 AM and 5 PM on days 29, 30, 34, 35, 40, and 41 of age. The observer sat down at 5-m distance from the plot to prevent impacting the birds’ behavior. The proportion (%) of the flock in the range, and at each distance were calculated.

|

Distance |

Silvopasture |

Open Pasture |

||

|

Photo |

Live |

Photo |

Live |

|

|

Near |

2.1 (0-33) |

7.3 (0-42) |

2.8 (0-31) |

4.7 (0-39) |

|

Middle |

0.2 (0-17) |

0.3 (0-11) |

0.2 (0-17) |

0.1 (0-5) |

|

Far |

0.1 (0-11) |

0.1 (0-8) |

0.1 (0-18) |

0.1 (0-19) |

|

|

Silvopasture |

Open Pasture |

||

|

Bird age (weeks) |

Photo |

Live |

Photo |

Live |

|

3 |

1.6 (0-8) |

- |

1.0 (0-6) |

- |

|

4 |

2.7 (0-21) |

5.1 (0-35) |

3.9 (0-38) |

2.4 (0-23) |

|

5 |

5.6 (0-37) |

10.2 (0-48) |

5.9 (0-32) |

5.2 (0-38) |

|

6 |

5.5 (0-41) |

8.0 (0-47) |

6.4 (0-48) |

6.9 (0-48) |

|

|

Silvopasture |

Open Pasture |

||

|

Time of day |

Photo |

Live |

Photo |

Live |

|

Morning |

3.9 (0-41) |

15.5 (0-48) |

5.0 (0-48) |

11.5 (0-48) |

|

Midday |

1.0 (0-13) |

1.2 (0-23) |

1.9 (0-38) |

0.2 (0-4) |

|

Afternoon |

1.8 (0-37) |

4.0 (0-36) |

1.7 (0-20) |

0.7 (0-27) |

|

Model |

AIC |

ΔAIC |

w_i |

|

~ToD×Age×Temperature+Treatment×Temperature |

11566.5 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

|

~ToD×Age×Temperature+Treatment |

11608.8 |

42.3 |

0.0 |

|

~ToD×Age×Temperature |

11812.8 |

246.3 |

0.0 |

|

~ToD×Age×Treatment |

11940.3 |

373.8 |

0.0 |

|

~ToD×Age+Treatment |

11987.4 |

420.9 |

0.0 |

|

~1 |

13221.3 |

1654.8 |

0.0 |

|

Model |

AIC |

ΔAIC |

w_i |

|

~ToD×Age×Temperature+Treatment×Temperature |

5168.6 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

|

~ToD×Age×Temperature+Treatment |

5189.2 |

20.6 |

0.0 |

|

~ToD×Age×Temperature |

5197.1 |

28.5 |

0.0 |

|

~ToD×Age×Treatment |

5268.2 |

99.6 |

0.0 |

|

~ToD×Age+Treatment |

5299.3 |

130.7 |

0.0 |

Fearfulness

Silvopasture birds showed shorter tonic immobility durations (79s vs 104s in Exp 1 and 59s vs 103s in Exp 2) than open pasture birds (p = 0.031 in Exp 1, and p < 0.001 in Exp 2). Shorter tonic immobility durations indicate less fear in the silvopasture treatment compared to the open pasture treatment.

Leg health: Silvopasture birds showed lower (better) footpad dermatitis scores than open pasture birds in Exp 1 and Exp 2 (p = 0.012 in Exp 1 and p = 0.004 in Exp 2). In Exp 1, 95% of silvopasture birds had no lesion on their footpads, compared to 83% in open pasture birds. In Exp 2, 85% of silvopasture birds had no lesions, compared to 66% in open pasture birds. In Exp 1, silvopasture birds showed lower hock burn scores, thus healthier hocks than open pasture birds (p = 0.049), with 85% vs 75% of birds showing no hock lesions respectively. In Exp 2, silvopasture birds tended to have lower hock burn scores than open pasture birds (p = 0.074), with 97% vs 91% of birds showing no hock lesions respectively. In Exp 1 but not in Exp 2, silvopasture birds had worse gait scores than open pasture birds (p = 0.019 in Exp 1 and p = 0.217 in Exp 2). Latency to lie did not differ between treatments in either experiment. The latency to lie for silvopasture vs. open pasture in Exp 1 was 452s vs 403s, and 523s vs 548s in Exp 2. These latencies indicate that leg strength was good in both treatments.

Economics

Feed conversion & animal growth: Animal daily gain and feed conversion were similar across treatments (Table 6).

Table 6. Mean ± standard error of live weights and carcass yields for both treatments and both experiments.

|

|

Treatment |

Spring 2021 |

Summer 2021 |

|||

|

On pasture |

On pasture |

|||||

|

Day 22-25 |

Day 25-42 |

Day 23-25 |

Day25-43 |

Day 1-43 |

||

|

Average daily gain (g) (mean ± SEM) |

Silvopasture |

56.88 ± 1.83 |

87.31 ± 2.53 |

40.96 ± 0.95 |

91.59 ± 2.85 |

62.61 ± 1.58 |

|

Open pasture |

54.45 ± 2.26 |

88.73 ± 1.96 |

42.53 ± 2.82 |

91.89 ± 1.93 |

62.97 ± 0.90 |

|

|

|

Treatment |

Day 22-25 |

Day 25-42 |

Day 25-42 |

Day 1-42 |

|

|

Adjusted FCR |

Silvopasture |

0.15 ± 0.01 |

1.20 ± 0.01 |

1.06 ± 0.02 |

1.73 ± 0.04 |

|

|

Open pasture |

0.17 ± 0.00 |

1.22 ± 0.03 |

1.07 ± 0.12 |

1.74 ± 0.03 |

||

Body weight and carcass yield (Table 7): Final body weights were recorded for 77-80 birds per treatment group in Exp 2. Final weights did not differ between treatments in Exp 1 (p = 0.883) or Exp 2 (p = 0.423). After each trial, 79-84 carcasses were used per treatment to determine carcass yield. These carcasses were cut and only included thighs with bone, wings with bone, and breast meat. Yield in either experiment did not differ between treatments (p = 0.378 in Exp 1 and p = 0.107 in Exp 2).

Table 7. Mean ± standard error of live weights and carcass yields for both treatments and both experiments.

|

Spring 2021 (Exp 1) |

Summer 2021 (Exp 2) |

|||

|

Silvopasture |

Open pasture |

Silvopasture |

Open pasture |

|

|

Live weight (kg) |

2.95 ± 0.042 |

2.96 ± 0.040 |

2.77 ± 0.043 |

2.80 ± 0.041 |

|

Carcass yield (kg) |

1.74 ± 0.024 |

1.70 ± 0.027 |

1.63 ± 0.024 |

1.58 ± 0.025 |

Environment

Temperature/humidity

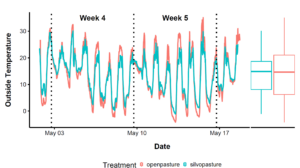

In Experiment 1, outside temperatures ranged from -1.1°C to 34.4°C in the silvopasture treatment and from -4.4°C to 36.7°C in the open pasture treatment. The silvopasture treatment maintained the same average temperature as the open pasture (16.7°C) but acted to buffer temperature extremes. Over the same period, coop temperatures ranged from 3.3°C to 43.3°C. In both treatments therefore, the coop buffered cold temperatures but consistently reached 11.1°C higher than outside temperatures (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Ambient temperature (°C) in the open pasture (red) and silvopasture (blue) treatments based on data from weather stations (1 per treatment).

Soil quality

We have collected soil samples before Exp 1 (baseline), after Exp 1, and after Exp 2. In between Exp 1 and 2, cattle were allowed to access the pastures used for the birds’ plots. Analysis of the baseline soil samples was performed in March 2021 in Dr. Sandeep Kumar's lab. Analysis of post-experimental soil samples was performed by Ward Laboratories, Inc. (Kearney, Nebraska), as Dr. Kumar left SD State University. An overview of collected soil samples is shown in Table 8.

Table 8. Overview of soil samples collected and current analysis status for Obj 1.

|

Sample collection date |

Time point |

Season |

Samples per treatment (n) |

Samples total (n) |

Samples analyzed (n) |

Samples to be analyzed (n) |

Analysis location |

|

3/3/2021 |

Baseline |

Spring |

6 |

12 |

12 |

0 |

SDSU |

|

21/5/2021 |

Post-experiment |

Spring |

24 |

48 |

12 |

36 |

Ward lab |

|

12/8/2021 |

Post-experiment |

Summer |

18 |

36 |

12 |

24 |

Ward lab |

β-Glucosidases are produced by a variety of organisms (plants, animals, fungi and bacteria; Esen, 1993). Monitoring β-Glucosidase activity can provide an early indication of changes in soil organic carbon. β-Glucosidase activity responds to management effects, and can serve as an indicator for soil metabolic functioning, with higher values indicative of better soil quality (Stott et al., 2010). The open pasture plots showed better soil quality compared to silvopasture, based on this indicator (p = 0.054; Table 9).

Phospholipid fatty acid content (PLFA) is considered a biological indicator of overall soil quality (Quideau et al. 2016). Values over 4,000 are considered indicative of excellent soil health. Samples at all time points showed excellent soil health (Table 9).

Total nitrogen is an indicator of soil fertility, and is required in high amounts during vegetation growth (Liu et al, 2022). Total nitrogen did not differ between treatments, but did improve after experiment 2 compared to after experiment 1 (Table 9). Organic nitrogen and nitrate levels did not differ between treatments or timepoints. Ammonium-nitrogen (NH4-N) concentrations of 2–10 ppm are considered normal, with values within normal range in both treatments (Table 9). Organic carbon is the main source of energy for soil microorganisms (total organic C). Levels were greater in the open pasture than the silvopasture treatment.

Table 9. Soil sample analysis outcomes (mean value) for samples collected at two timepoints in both treatments.

|

Spring 2021 |

Summer 2021 |

Treatment effect (P-value) |

Time point effect (P-value) |

|||

|

Post-experiment 1 |

Post-experiment 2 |

|||||

|

Open pasture |

Silvo-pasture |

Open pasture |

Silvo-pasture |

|||

|

Beta Glucosidase (ppm pNP kg-1 soil h-1) |

172 |

126 |

156 |

113 |

0.003 (OP>SP) |

NS |

|

Total PLFA |

22,289 |

19,403 |

18,639 |

20,179 |

NS |

NS |

|

Total nitrogen (H2O Total N in mg/kg) |

47 |

45 |

65 |

63 |

NS |

0.006 (post1<post2) |

|

Organic nitrogen (H2O Organic N ppm) |

20 |

14 |

17 |

25 |

NS |

NS |

|

Nitrate (H2O NO3-N ppm) |

25 |

29 |

46 |

36 |

NS |

NS |

|

Ammonium-nitrogen (H2O NH4-N ppm) |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

NS |

0.051 (post1>post2) |

|

Total Carbon (H2O Total Organic C ppm) |

206 |

178 |

190 |

169 |

0.012 (OP>SP) |

0.065 (post1>post2) |

|

Acid Phosphomonoesterase (mg pNP kg-1 soil h-1) |

412 |

304 |

401 |

283 |

<0.001 (OP>SP) |

NS |

|

Alkaline Phosphomonoesterase (mg pNP kg-1 soil h-1) |

275 |

157 |

248 |

142 |

<0.001 (OP>SP) |

0.090 (post1>post2) |

Insect diversity

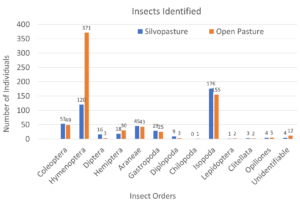

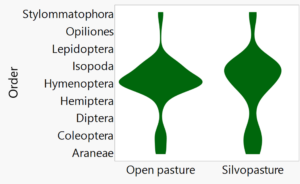

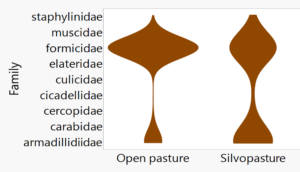

Using pitfall traps (1 per plot) in Experiment 1, we determined insect biodiversity in each treatment group. Insects were visually identified at the order and family level from 12 traps in the silvopasture system and 9 traps from the open pasture system. A total of 478 insects from the silvopasture system and 701 insects from the open pasture system were identified from the pitfall traps (Figure 2a). The difference in insect numbers were primarily caused by the difference in number of Hymenoptera (ants; Figure 2b).

Figure 2. Total insect counts (n) per treatment presented by taxonomic order or family. A) Absolute counts by order. B) Relative proportion by order. C) Relative proportion by family.

We calculated the biodiversity index for both treatments. The biodiversity index is calculated based on the number of species compared to the number of individuals (index=species/individuals). While we have not defined the number of species, we can estimate this index based on the number of orders (orders/individuals) and families (families/individuals) observed. Species richness reflects the absolute number of different species in a location. Again, we can translate to "order richness" and "family richness".

Overall, the silvopasture system had a more even distribution of insects both at the order level and the family level compared to the open pasture system (Figure 2b and 2c). In alignment, the biodiversity indexes were higher (better) for the silvopasture system compared to the open pasture system (Table 10). All these results indicate that even though more insects were identified in the open pasture compared to the silvopasture, insect biodiversity seemed better in the silvopasture plots in experiment 1.

Table 10. Insect diversity, with the richness and biodiversity index by treatment. The n reflects the number of insects identified to the order or family level.

|

|

Order richness |

n |

Family richness |

n |

Biodiversity Index |

|

|

Order |

Family |

|||||

|

Open pasture |

12 |

689 |

7 |

460 |

0.017 |

0.015 |

|

Silvopasture |

11 |

474 |

7 |

240 |

0.023 |

0.029 |

Objective 2A - Field trial: Compare broiler chicken production with access to a newly planted silvopasture on a large-scale commercial farm to grass pasture access on the same farm

Due to limitations related to the pandemic, we could not visit the cooperating farm early in 2021. Further delays were caused by challenges related to identifying certified organic vegetation to plant in the pasture. Because of seasonal limitations, planting of vegetation at the commercial farm had to be postponed to the spring of 2021 (3/3/2021). A new challenge has arisen this year (2021-2023) with the spread of highly-pathogenic avian influenza across the US.

Animal welfare and economics

Data collection on animal welfare and animal productivity (economics) measures was completed for two flocks in August 2022, one flock with access to a silvopasture, and one with access to an open pasture. Birds were a fast-growing strain (Cornish cross) of 27 and 28 days of age. Eighty birds per flock were sampled.

It is important to note that a scientific comparison of two flocks cannot be made. However, we found that birds in the open pasture flock (OP) were more fearful than birds in the silvopasture (SP) flock, with mean tonic immobility durations of 130 sec in OP versus 75 sec in SP. We observed worse gait scores in the open pasture flock compared to the silvopasture flock, with 51% of birds scoring 0 (perfect gait) in OP versus 73% in SP, 45% of birds scoring 1 (awkward gait) in OP versus 25% in SP, and 4% of birds scoring 2 (unable to walk 1.5 ft) in OP versus 2% in SP. We observed better footpad dermatitis scores in the open-pasture flock compared to the silvopasture flock (54 vs 47% of birds in score 0 for OP vs SP; 18 vs 20% score 1 for OP vs SP; 28 vs 25% score 3 for OP vs SP), but hock burns did not differ between flocks as most birds had no hock lesions (score 0: 95% in OP and 96% in SP).

Birds in the silvopasture flock were lighter than birds in the open pasture flock, with a mean of 3.80 lbs live weight in SP versus 4.51 lbs in OP.

Soil quality

Six baseline soil samples were collected from two pastures (silvopasture versus open pasture), and sample analysis was performed in March 2021 in Dr. Kumar's lab. Six additional samples were collected from the same two pastures in November 2022 and sample analysis was performed by Ward laboratories (Table 11).

Table 11. Soil sample analysis outcomes (mean value) for samples collected at two timepoints in both treatments.

|

|

Open pasture |

Silvopasture |

||

|

Baseline March 2021 |

Nov 2022 |

Baseline March 2021 |

Nov 2022 |

|

|

Hot waterTC (ppm) |

156.4 |

. |

186.1 |

. |

|

Hot waterTN (ppm) |

18.1 |

. |

20.2 |

. |

|

Cold waterTC (ppm) |

40.2 |

. |

44.0 |

. |

|

Cold waterTN (ppm) |

4.1 |

. |

4.9 |

. |

|

Acid phosphotase |

36.5 |

. |

30.8 |

. |

|

Beta glucosidase |

260.4 |

. |

297.3 |

. |

|

Urease |

2.4 |

. |

2.0 |

. |

|

Glomalin |

4.1 |

. |

4.7 |

. |

|

TC Fumigated (ppm) |

86.9 |

. |

137.2 |

. |

|

TN Fumigated (ppm) |

11.7 |

. |

16.3 |

. |

|

TC non-fumigated (ppm) |

27.5 |

. |

32.6 |

. |

|

TN Non-fumigated (ppm) |

4.0 |

. |

6.8 |

. |

|

Gram Negative |

37.4 |

. |

15.0 |

. |

|

Gram Positive |

45.2 |

. |

19.5 |

. |

|

Actinomycetes |

15.7 |

. |

8.7 |

. |

|

Total bacterial biomass |

82.6 |

. |

34.5 |

. |

|

Total Fungi |

7.2 |

. |

5.5 |

. |

|

Total PLFA |

105.6 |

. |

48.6 |

. |

|

H2O Total N |

. |

102.9 |

. |

73.7 |

|

H2O Organic N |

. |

19.4 |

. |

26.2 |

|

H2O Total Organic C |

. |

219.7 |

. |

240.3 |

|

H2O NO3-N |

. |

80.2 |

. |

44.3 |

|

H2O NH4-N |

. |

3.3 |

. |

3.2 |

|

Beta Glucosidase ppm pNP g-1 soil h-1 |

. |

183.8 |

. |

172.5 |

|

Phosphomonoesterases (Acid) ppm pNP g-1 soil h-1 |

. |

454.3 |

. |

325.7 |

|

Phosphomonoesterases (Alkaline) ppm pNP g-1 soil h-1 |

. |

196.5 |

. |

194.0 |

Objective 2B - Field trial: Compare broiler chicken production with access to established silvopastures on two small-scale commercial farms to grass pasture access on the same farms

Due to limitations related to the pandemic, we could not visit the cooperating farms in 2020. We visited the farm in Virginia in 2021, 2022, and 2023 (Brent Wills’ farm), and collected data from three rounds of broiler chicken production (3 flocks per round). For each production round, two plots (approx. 65 Freedom Rangers/plot) were set up, one with access to open pasture, one with access to some silvopasture-like vegetation. Approximately 60 birds were sampled per flock at 56, 63 or 67 days of age.

Virginia small-scale farm

Economics

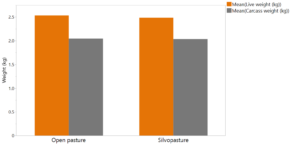

There were no significant differences in live weight and carcass weight outcomes across years and treatments (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Mean bird live weights and carcass weights (kg) when housed with or without canopy cover (based on data from 6 flocks across 3 years).

Animal welfare

Footpad and leg health

Birds in silvopasture had healthier footpads (more birds with a score 0 than in open pasture; Table 12). Across years, mean footpad dermatitis scores were better in silvopasture compared to open pasture (OP = 0.36 ± 0.11, SP = 0.19 ± 0.11; F = 9.93; P = 0.0018). Generally, most birds had healthy footpads or only a small lesion (score 1).

Table 12. Proportion (%) of birds per footpad dermatitis score (higher scores represent more severe lesions) by pasture treatment (2021-2023 data)

| Footpad dermatitis score (0-4) | |||||

| Season | Treatment | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 2021 | Open pasture | 53 | 26 | 19 | 2 |

| Silvopasture | 77 | 17 | 6 | 0 | |

| 2022 | Open pasture | 83 | 12 | 4 | 1 |

| Silvopasture | 91 | 9 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2023 | Open pasture | 84 | 16 | 0 | 0 |

| Silvopasture | 82 | 18 | 0 | 0 | |

Most birds had healthy hocks or only a small lesion (Table 13). No difference between silvopasture or open pasture treatments was found.

Table 13. Proportion (%) of birds per hock burn score (higher scores represent more severe lesions) by pasture treatment (2021-2023 data)

|

|

Hock (0-4) |

|||

|

Season |

Treatment |

0 |

1 |

|

|

2021 |

Open pasture |

91 |

9 |

|

|

|

Silvopasture |

81 |

19 |

|

|

2022 |

Open pasture |

97 |

3 |

|

|

|

Silvopasture |

100 |

0 |

|

|

2023 |

Open pasture |

95 |

6 |

|

|

|

Silvopasture |

93 |

8 |

|

Most birds had excellent gait (Table 14). Across years, gait was worse (more lameness) in open pasture birds compared to silvopasture birds (OP = 0.21 ± 0.08, SP = 0.11 ± 0.08; F = 5.7; P = 0.018).

Table 14. Proportion (%) of birds per gait score (higher scores represent more lameness) by pasture treatment (2021-2023 data).

| Gait score (0-2) | ||||

| Season | Pasture treatment | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 2021 | Open pasture | 98 | 2 | 0 |

| Silvopasture | 96 | 4 | 0 | |

| 2022 | Open pasture | 59 | 41 | 0 |

| Silvopasture | 85 | 13 | 2 | |

| 2023 | Open pasture | 82 | 18 | 0 |

| Silvopasture | 85 | 15 | 0 | |

Fearfulness

A longer duration reflects more fear induced during the test (Table 15). Generally, most birds show short tonic immobility durations relative to other research. Across years, no difference in fearfulness between treatments was observed (F = 0.23; P = 0.63).

Table 15. Mean duration of tonic immobility (sec) by pasture treatment (2021-2023 data)

| Tonic immobility duration (sec) | |||

| Season | Treatment | Mean | Std Err |

| 2021 | open pasture | 54 | 5 |

| silvopasture | 66 | 6 | |

| 2022 | open pasture | 56 | 5 |

| silvopasture | 65 | 6 | |

| 2023 | open pasture | 122 | 13 |

| silvopasture | 109 | 12 | |

Environment

Soil quality: Baseline and post-trial soil samples were collected from two pastures (Table 16).

Table 16. Soil sample analysis outcomes (mean value) for samples collected in both plots, before and after the production rounds.

|

|

Open pasture |

Silvopasture |

||||

|

Baseline |

Post-experiment |

Baseline |

Post-experiment |

|||

|

2021 |

2021 |

2022 |

2021 |

2021 |

2022 |

|

|

Beta glucosidase |

35.2 |

68.4 |

45.2 |

30.8 |

35.0 |

42.4 |

|

Total PLFA |

5300 |

5932 |

|

44837 |

5167 |

|

|

H2O Total N |

44.9 |

35.1 |

33.7 |

42.0 |

32.2 |

36.7 |

|

H2O Organic N |

11.6 |

13.9 |

8.3 |

6.2 |

8.8 |

6.4 |

|

H2O Total Organic C |

98.0 |

139.3 |

164.0 |

86.3 |

115.7 |

161.3 |

|

H2O NO3-N |

31.6 |

18.3 |

23.2 |

33.8 |

21.0 |

27.9 |

|

H2O NH4-N |

1.6 |

3.0 |

2.3 |

1.9 |

2.4 |

2.3 |

|

Phosphomonoesterases (Acid) ppm pNP g-1 soil h-1 |

93.3 |

163.3 |

108.2 |

90.6 |

113.3 |

116.7 |

|

Phosphomonoesterases (Alkaline) ppm pNP g-1 soil h-1 |

47.4 |

90.3 |

87.9 |

25.4 |

44.7 |

50.8 |

Minnesota small-scale farms

Two small-scale broiler chicken farms were visited in August 2022 and data were collected on animal welfare outcomes and live body weights as a proxy for productivity.

5-year-old silvopasture: One farm consisted of a 1.5-acre plot with 200 hazelnut trees of approx. 5-years old. This plot housed 1,500 Royal Grey broilers. Here, 84 birds were sampled at 67 and 68 days of age.

40-year-old silvopasture: The second farm consisted of a 1.5-acre plot heavily planted with 40-year-old ornamental trees. A single flock of 1,300 mixed slow-growing broilers was raised. Here, 68 birds of 72 days-old were sampled.

Although no true scientific comparison between farms can be made, we found no differences between silvopasture farms in leg health outcomes, with excellent scores in both farms (Table 17). Fear seemed to differ between farms, with longer TI durations in the 5-year-old silvopasture compared to the 40-year-old silvopasture (mean duration of 160 sec vs 122 sec respectively). Birds in the 5-year-old silvopasture were lighter (5.5 lbs) than birds in the 40-year-old silvopasture (6.2 lbs), however it is important to note that these were different genetic strains and birds ages differed.

Table 17. Proportion (%) of birds per footpad dermatitis score, hock burn score, and gait score by farm

|

FPD score (0-4) |

Hock score (0-4) |

Gait score (0-2) |

|||||||

|

0 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

|

|

5-year-old silvopasture |

97 |

0 |

3 |

100 |

0 |

0 |

92 |

8 |

0 |

|

40-year-old silvopasture |

99 |

1 |

0 |

100 |

0 |

0 |

97 |

3 |

0 |

Objective 3A - Surveying silvopasture-poultry producers about their experiences, concerns and opportunities for applying these practices

Three poultry farmers were interviewed for a qualitative survey of silvopasture-like systems (interviews were performed as approved by the Virginia Tech Institutional Review Board (protocol number 23-387).

FARM 1: MEADOWDALE FARM IN EAST TENNESSEE

Background

This farm is located in East Tennessee with a distinct mix of various farming activities within the farm. It is a family-operated farm where they are involved in logging and sawing business along with farming. The producer began farming in the early 2000s in the Northeastern United States and later moved to east Tennessee and has been operating farm since 2022. The producer is within the age category of 25-44 years and has completed high school and pursued over three years of college education. The primary sources of household income come from the logging business (89%) followed by selling tree products (10%), and poultry operation (1%). The farm has 200 acres of farm area among which 25 acres are owned and 175 acres are rented. The farm has 20 acres of silvopasture within the owned acreage while most of the rented land is used primarily for hay production.

Personal Motivation/Experience

The producer began exploring the concept of silvopasture in the early 2010s, inspired by historical documentation and modern writings, particularly those by Eric Toensmeier. Motivated by the desire to improve animal welfare, reduce external inputs for pest control, and enhance food quality, the producer got interested in silvopasture as a means to utilize less-than-prime farmland effectively. A self-taught practitioner who also participated in conferences and various regenerative agriculture organizations and groups, the producer initially used barn-based structures before moving to mobile setups. Participation in a Forest Chicken grant helped pivot towards raising egg layers within wooded environments, although some tracking activities were disrupted by the pandemic. The climate change considerations did not play a role in the producers’ decision to adopt poultry silvopastures. Producers’ concern regarding climate change primarily revolves around fluctuating grain prices, impacting feed costs, rather than direct environmental impacts.

Establishment and Management of Silvopasture

The producer began farming in early 2000 in Vermont but later on, moved to Tennessee and started farming in 2022. The land used for farming, previously used for agriculture until the mid-20th century, was reclaimed from forest and invasive species. The silvopasture system in the farm was established in 2022 by thinning mature forests, with an emphasis on sustainable and selective logging facilitated by the producers’ spouse, who is a logger and sawyer. During the thinning process, all the potentially toxic trees (cherry and black walnut) within the site were also removed. The silvopasture site consists of different tree species such as sweet gum, various oaks, tulip poplar, maples, cedar, hemlock, yellow pine, hackberry, hickory, black walnut, and cherry. About 100 trees per acre are maintained to provide canopy cover and habitat diversity. Over the next two years with more timber harvesting, the producer is planning on planting a variety of warm-season native grasses such as switchgrass, Virginia wild rye, Eastern Gama grass, side oats Gama, Indian grass, little/big bluestem underneath the trees. The producer is in the preliminary stage of silvopasture establishment and plans to implement some of the establishment and management activities within the silvopasture site that includes application of biochar, installing perimeter fencing and water systems, and setting up bird housing infrastructure. The producer also plans to undertake mulching, reseeding areas disturbed by birds, cleaning up downed trees, and storm damage within the silvopasture site as needed.

Poultry and Livestock Management

The producer prioritizes breeds known for their robust leg health and their ability to thrive on a forage-based diet for poultry production. The producer manages Cornish crosses raised for meat and Red Star or Bard Rocks, chosen for egg production. The producer also manages various other small-scale livestock operations within the farm including Hereford x Holstein cattle, Katahdin lambs, Mangalica pigs, giant white turkeys, and Pekin ducks.

To address common leg health issues in birds, the producer supplements the birds' diets with Vitamin-B-enriched electrolytes and provides tender forages like clovers. In the pasture, the producer allows the feed to run out to encourage the birds to graze more actively on natural forages. The birds are moved twice daily, which not only promotes grazing but also provides exercise, further improving leg health concerns. This routine is enhanced with occasional treats such as worms and seeds, making the foraging experience both nourishing and enjoyable. These management practices have significantly reduced leg problems on the farm. While the farm has experimented with heritage bird varieties, the producer mentioned that the higher resources these birds demand made them less viable. The newer breeds offer a more practical solution by growing faster and yielding more meat.

For the layers, the challenge of seasonality is managed by selecting breeds that blend into the environment, thus protecting them from predators like hawks and owls. The producer is considering making a shift to Rhode Island reds to match the farm's red soil, enhancing the birds' camouflage. The farm operates on a scale of 100-150 birds per batch for both broilers and layers, with a typical cycle lasting two years for layers. While purchasing pullets seems economically sensible, it poses challenges as these birds often appear more tense than those raised on the farm, suggesting a difference in adaptability and ease within the farm environment.

Challenges and Innovations

The main challenges include managing poisonous plants and handling birds amidst dense foliage, which complicates the use of solar chargers and increases exposure to pests like ticks. Solutions have included using permethrin-treated clothing and advocating for more flexible agricultural support programs. Significant labor and resource inputs have been directed toward logging, site preparation, soil amendments, and infrastructure development over several years. The producer uses personal labor extensively alongside hired help, employing a range of equipment from chainsaws to excavators.

Bird Health and Welfare

The farm experienced minimal disease issues thanks to proactive health management strategies, including the use of apple cider vinegar and garlic in water, probiotics in feed, and natural dewormers. However, the producer does encounter some domestic dog attacks resulting in significant losses. The adoption of silvopasture has generally improved the welfare of the birds, providing them with stimulating environments that reduce stress behaviors and mortality. Challenges persist with predator breaches (dogs, owls, eagles), but the overall effect on bird happiness and potential egg production is positive. Compared to previous practices, silvopasture has enriched the behavioral environment for the poultry, contributing positively to both bird health and the general atmosphere of the farm.

Ecological and Recreational Aspects

The producer mentioned that the silvopasture adoption has resulted in significant ecological benefits such as enhanced soil health, water retention, and resilience against drought and floods. The presence of poultry following cattle has also helped in breaking down cow pies and enhancing soil fertility. While the silvopasture system has improved the presence of beneficial insects, it has also negatively impacted larger wildlife due to fencing and active land use. The silvopasture areas provide recreational benefits, such as walking, enhancing the quality of life for the producer and their family.

Marketing and Economic Aspects

The unique aspects of silvopasture are leveraged in marketing strategies to educate consumers and justify premium pricing. Products are primarily sold directly to consumers, at local restaurants, and high-end grocery stores. Currently, there are no certifications for poultry products, largely due to the perceived extra workload without proportional benefits.

Social and Policy Aspects

Community responses have been mixed, with some appreciating the traditional farming approach while others question the animal welfare implications. Challenges with local agricultural extensions reflect broader cultural and regional differences in agricultural practices. Limited eligibility for financial incentives and support programs has been a barrier, though specific grants have occasionally supported infrastructure improvements.

Future Directions and Feedback

Poultry silvopasture is a fundamental component of the farm's system, improving the efficiency of ruminant grazing by controlling parasites and managing manure. Expansion plans include scaling up egg production and enhancing coop construction. New practitioners are encouraged to join associations and leverage community knowledge. Practical advice includes realistic planning around profitability and the integration of multiple farming enterprises to balance workload and financial outcomes.

FARM 2: TREE RANGE POULTRY OPERATION IN LAKEVILLE, MINNESOTA

Background

This farm is located in Lakeville, Minnesota and the producer managing the farm is within the age category of 25-44 years with an academic background in Culinary Arts holding a 2-year Associate of Arts degree. Since relocating to the farm in 2020, the producer’s primary source of income has been external, not directly related to farming activities. The farm has 12.43 acres of land area, with land use distributed across silvopasture (3 acres), woodland/forestland (6.43 acres), horticultural crops (1-acre starting), and conservation areas (2 acres).

Personal Motivation/Experience

The producer’s interest in silvopasture was sparked by concerns over rainforest loss, a familial background in organic farming, and a heightened awareness of sustainable agriculture practices gained through attending field days, workshops, and extensive online research. Motivated by the desire to maximize land use efficiently while addressing environmental concerns, the producer chose to implement a poultry silvopasture system primarily because it required less space and could be managed more efficiently compared to other livestock. The climate change consideration did not affect the producers’ decision to adopt poultry silvopasture but the producers believe that there will be a water shortage in the near future and want trees to retain moisture on the farm.

Establishment and Management of Silvopasture

The farmland was previously used for hay production and was also occasionally used for growing beans and corn. The transition of the land to silvopasture began in 2023 with the planting of 400 hazelnut trees, supplemented by an additional 100 to follow. This initial stage of silvopasture establishment required significant manual labor but no hired help, reflecting a strong community or family effort. To protect the young hazelnuts from rabbits, deer, and chickens, plans were made to fabricate and install cages, anticipating the use of wire rolls cut to fit around the trees. The silvopasture site has a tree density of about 200 trees per acre. The forage species within the silvopasture site include Orchardgrass, clover, alfalfa, and various weeds that chickens like such as burdock and lamb’s quarter. Additionally, crops such as barley, oats, flax, comfrey, and amaranth are planted as alley crops. The producer has not yet introduced birds within the silvopasture and plans to do so in July 2024 with a single flock of birds. Other tree species planted within the silvopasture site include Ash, Maple (white, red, silver), oak (pin and red), elm, and black cherry. Some of the management practices within the site have included selective thinning of trees, strategic planting, and addressing challenges such as soil erosion following trenching efforts. Clearing invasive buckthorn and mowing ground cover are also some of the periodic management activities carried out by the producer.

Poultry and Livestock Management

The farm aims to manage three flocks of 1,500 'Freedom Rangers' and 'Royal Grey' birds annually. This breed selection is strategic, aligning with the farm's commitment to sustainable and regenerative farming practices. The producer also plans to integrate goats within the operation in the near future but will have to consider proper fencing and tree protection along with the potential toxicity of elderberry to these animals before integrating any ruminants within the silvopasture site.

Challenges and Innovations

Some of the initial challenges that the producer has faced include high start-up costs and navigating zoning laws. Training and adjustments in management practices are ongoing to optimize both poultry health and land productivity.

Bird Health and Welfare

The producer has the over mortality rates of birds at 5% or lower. This achievement is largely attributed to the innovative incorporation of medicinal herbs and sprouted grains into the birds' diets, coupled with high protein and low fiber formulations that promote optimal health. While the specifics on the direct impacts of silvopasture on bird welfare and any observed behavioral changes were not detailed, the overall low mortality rate suggests a positive environment conducive to bird health and productivity. The farm's approach, focusing on nutritional enhancements and possibly the natural shelter and foraging opportunities offered by silvopasture, appears to support a healthier and more productive poultry population compared to conventional poultry management practices.

Ecological and Recreational Aspects

Since implementing silvopasture, improvements in soil health have been noted, including an increase in earthworm populations—a positive indicator of soil vitality. The farm also provides recreational benefits such as exercise and educational opportunities for family members, particularly in understanding and participating in sustainable farming practices.

Marketing and Economic Aspects

The poultry products are marketed under the Tree Range strategy, which emphasizes the ecological benefits of silvopasture. This strategy has attracted customers interested in high-nutrient, ethically raised products, thus providing a premium market niche for the farm’s outputs.

Social and Policy Aspects

Community responses have been mixed, with some curiosity and a lack of understanding about the non-conventional poultry management methods used. Regulatory challenges have been minimal, though the farm seeks to expand its operations, pending appropriate permits and potential financial incentives.

Future Directions and Feedback

Looking ahead, the producer plans to refine the management processes, expand marketing efforts, and possibly scale up the operation by integrating additional barns. Reflecting on the journey, the producer recommends careful planning and layout considerations for others interested in silvopasture, emphasizing the importance of not overcrowding plantings and thoroughly understanding the specifics of silvopasture management.

FARM 3: ORGANIC COMPOUND FARM IN FARIBAULT, MINNESOTA

Background

This case study explores a pioneering approach to agriculture—poultry silvopasture, through the lens of an innovative producer who has merged his backgrounds in digital marketing and filmmaking with his passion for regenerative agriculture. The producer is within the age category of 25-44 years and has completed a bachelor’s degree in Filmmaking. The producer transitioned from an early disinterest in agriculture to developing a diverse and ecologically sustainable farming operation. The farm manages approximately 40 acres, among which 7 acres are owned and additional land rented. This land supports various agricultural activities including silvopasture, woodland management, and vegetable cultivation. The farm's income is diversified, with 20% derived from broiler chicken production, 5% from vegetation, and the remaining 75% from other sources, notably digital marketing.

Personal Motivation/Experience

Initially indifferent to agriculture at his young age, the producer's perspective shifted dramatically following a series of inspiring travels that included Europe and Hawaii. These travels developed a passion for growing food and gardening, eventually leading the producer down the path of learning about agroforestry and permaculture. By 2013 and 2014, the producer’s connection with figures like Mark Shepard further solidified the interest, and the producer began to seriously invest in planting hazelnuts by 2014 and developing the entire farm by 2016 and 2018.

The producer’s introduction to poultry silvopasture was less about formal education and more about practical engagement and networking within the permaculture and regenerative agriculture communities. The producer's transition into this field was catalyzed by relationships forged with key individuals in the agroforestry network, like Mark Shepard, Dan Halsey, Lizzie Rebhan, and Paulo Westmoreland. These interactions enriched the producers’ understanding and enthusiasm for integrating livestock with tree-cropping systems. Additionally, the professional background of the producer as a digital marketer enabled the producer to create and leverage online platforms such as learnagroforestry.com and regenpoultry.com, enhancing the knowledge and network of the producer in the field. While climate change was not the primary motivator for the adoption of poultry silvopasture, the producer is deeply invested in the broader environmental benefits that this approach offers, such as ecosystem restoration, clean water, and healthy soil. These benefits align with the producer’s vision of creating a sustainable farming operation that not only produces food but also contributes positively to the surrounding environment.

Establishment and Management of Silvopasture

The farmland was before in alfalfa-corn-soy rotation. The producer rented the land for a time from family before acquiring it. The establishment and management of the silvopasture on the farm began in earnest in 2016 with a variety of tasks aimed at integrating tree planting with pasture management. The process started with the planting of a barley and clover mix across 40 acres, using the tractor and a rented no-till drill. In parallel, hazelnut trees were planted with the help of a large group consisting of family, friends, and volunteers. The silvopasture site has a tree density of up to 1000 hazelnut trees per acre in chicken paddocks. Forage species within the silvopasture site include Clover and Orchardgrass-based pasture mix. However, the Broadacre site has a 17-species mix (tillage radish, daikon, sunflower, multiple clovers, buckwheat). The producer reseeds clover as bare areas seen within the paddocks. Further farm diversification occurred with the planting of additional hardwood trees, deer deterrents like lilac, and an expansion into crops such as asparagus in 2018. By 2019, tree protective measures were implemented using green welded wire and rebar to safeguard both new and overstory trees. Regular maintenance within the silvopasture site included mowing three times per year using a tractor with a flail mower, a task consistently managed by a family member, and detailed hand weeding around trees that engaged both event volunteers and hired labor, employing tools like machetes. Row mulching commenced in 2019, utilizing wood chips and specialized equipment to maintain soil health and moisture. Some of the ongoing annual maintenance activities included further mowing, mulching with contributions from both unpaid and eventually paid labor using shared equipment, focused weed management by hired workers, sporadic gopher trapping, and minimal watering.

Poultry and Livestock Management

Currently, the farm operates with high-density chicken paddocks (up to 1,000 hazels per acre) and manages rotational grazing systems to maintain soil health and pasture vitality. The poultry, primarily Freedom Ranger and Royal Grey breeds, are reared in six flocks annually, totaling 9,000 birds per year. This method of pasture management is complemented by the integration of Mangalica pigs and goats, enhancing the ecological benefits of silvopasture without the use of intensive mechanical farming methods. The implementation of silvopasture began with the strategic introduction of poultry shortly after the trees were established, with protective caging around the young saplings. The progression has been steady and strategic: starting with a single flock in 2017, the number increased to three by 2018. After mostly completing the caging in 2019, the farm expanded further in 2020 with the construction of a second barn and raising five flocks in 2021, eventually stabilizing at six flocks. While the integration of goats and pigs has been successful, there's a keen interest in adding sheep to the mix. The producer sees great potential in sheep for reducing the need for mowing, enhancing soil fertility, and providing additional income, but is proceeding cautiously, determined to master one element at a time in the complex system of silvopasture.

Challenges and Solutions

The transition to poultry silvopasture was not without its challenges. Initially, the producer faced issues such as underfeeding, water logistics, and the physical demands of managing tree crops without prior experience. The producer overcome these obstacles through community engagement and educational events that both solved immediate labor needs and built a knowledgeable volunteer base.

Bird Health and Welfare

In the area of bird health and welfare, the producer has navigated through a spectrum of challenges and adaptations, particularly as they pertain to the integration of poultry into a silvopasture system. Initially, the health of the birds was compromised by several factors including stress-related mortality during loading, which often resulted from moving too quickly, and similar issues when the birds were first released onto pasture. Other notable challenges included environmental stressors such as heat waves, which were particularly taxing in barns with inadequate ventilation, though one barn’s solarium did offer some relief. Additionally, the birds faced threats from natural elements and predators, with incidents like feeders being blown over by strong winds, or attacks from untrained dogs and predatory hawks.

However, the adoption of poultry silvopasture has gradually begun to enhance the welfare of the birds. The evolving landscape, which initially offered little shade, has transformed as the bushes and other vegetation matured, providing more natural cover. This development has noticeably encouraged the birds to venture out more frequently and for longer durations, without the need for artificial shade structures. The producer observed an apparent sense of security among the birds in this more dynamic and protective environment. While there were no data recorded, there were anecdotal observations suggesting improvements in meat quality and feed conversion rates compared to previous poultry management practices. These changes highlight a positive shift in both the behavior and health of the birds, underscoring the benefits of silvopasture in fostering a safer and more conducive environment for poultry.

Ecological and Recreational Aspects

Since transitioning from a conventional corn field to a silvopasture system, the farm has experienced a remarkable transformation in its ecological health and overall ambiance. The introduction of this system has enriched the soil, evident from the increase in organic matter and improved water infiltration. This healthier soil supports a diverse range of plant and animal life, enhancing the farm's biodiversity and attracting wildlife such as owls and hawks, as indicated by the occasional discovery of feathers. The producer enjoys the land much more now; it's not only a place of agricultural production but also a space for recreation and connection with nature. Riding a 4-wheeler through the farm reveals many unique spaces that have emerged with the growth of new vegetation and the presence of various wildlife, marking a significant shift from the farm’s previous agricultural practices.

Marketing and Economic Aspects