Final report for FNE24-092

Project Information

Purpose:

This project aimed to assess whether engaging in at least 2.5 hours of weekly farming or gardening could improve health outcomes, reduce stress, and enhance food access and agricultural education among communities near Camden, New Jersey.

Methods:

The Tuba Farm Foundation implemented a no-till farming initiative involving farmers, students, volunteers, and community members within a 20-mile radius of Camden. Participants committed to a minimum of 2.5 hours per week of farming or gardening activities, aligning with CDC guidelines for moderate-intensity physical activity. The program also included educational workshops on nutrition and sustainable agriculture practices to increase knowledge and self-confidence in gardening and farming. Data collection focused on health outcomes, stress levels, dietary habits, and social engagement.

Results and Assessment:

Preliminary results indicate that the program had a positive impact on participant health and well-being. There were significant improvements in physical activity levels, farming knowledge, and community engagement. A marked increase in average daily steps directly correlated with improved health metrics for all participants. While quantitative data did not show a measurable reduction in stress, qualitative feedback suggests that participants experienced a reduction in stress, reinforcing the therapeutic and health-promoting benefits of farming. These findings underscore the potential of farming and gardening as sustainable forms of exercise and community-building, contributing to both physical health and overall well-being.

Outreach:

The initiative reached a diverse group of community members, including farmers, students, and adults in the Camden area. Through hands-on participation and educational workshops, the project fostered community engagement and promoted sustainable agriculture. Results and lessons learned will be shared more broadly to inspire similar programs in other communities.

The objectives of this no-till farming initiative are to improve health outcomes, increase food/nutrition and farming education, and encourage access and consumption of healthy food grown by farmers, our families, students, volunteers, and community members within 20 miles of, local food desert, Camden, NJ. This program will help build an equitable food system; increase healthy food production and access; train and encourage new farmers, encourage physically and mentally healthier communities, and increase the propensity for communities to grow food sustainably, at a low-cost. Tackling health and food insecurity, head-on.

This program looks to answer the following questions: Does farming/gardening as a moderate intensity exercise, for at least 2.5 hours weekly, improve health outcomes? Does farming/gardening as a moderate intensity exercise, for at least 2.5 hours weekly, reduce stress? Does increasing food and nutrition knowledge result in healthier choices? Does increased farm training improve knowledge of low-cost, and sustainable agriculture methods? Does increased farm training/workshops increase gardening/farming self-confidence? Does growing your own food and increasing access encourage consumption of fruits and vegetables? Does utilizing Tuba Farm as a community gathering space, improve the number and quality of social interactions and civic engagements?

Health Problems: According to the USDA, more than 4 in 10 American adults have obesity. One in two has diabetes or prediabetes. Black and Indigenous children are more likely to have obesity than their white peers (USDA, 2022). The risk of adult obesity is greater among adults who had obesity as children, and racial and ethnic disparities exist by the age of 2(Petersen, 2019). Additionally, low-income individuals and members of racial/ethnic minority groups are disproportionately exposed to stress and face greater threats to health, safety, and economic advancement(APA,2017). Another group greatly affected by stress, farmers and ranchers, are nearly two times more likely to die by suicide in the U.S., compared to other occupations. (Peterson, 2016). Beyond the effects on health, poor nutrition and diet-related diseases have far-reaching impacts including decreased academic achievement and increased financial stress.

To improve diet, physical activity, weight outcomes and stress levels, among underserved farmers and adults, this program looks to provide consistent physical activity, increased education, frequent social engagements, and more access to healthy affordable food for consumption.

According to the CDC, moderate-intensity level activity for 2.5 hours each week can reduce the risk for obesity, high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, osteoporosis, heart disease, stroke, depression, colon cancer and premature death. The CDC considers gardening a moderate-intensity level activity and can help achieve that 2.5 hour goal each week (Darton, 2014).

As such, participants must commit 2.5 hours of weekly farming and gardening to achieve the USDA physical activity recommendations. Connecting and interacting with nature through farming has many health benefits, and the benefits of community farming go beyond improving diet, physical activity, and weight outcomes. Tuba is encouraging collective farming activities to improve mental wellbeing through social interaction, community building and engagement, and greater life satisfaction among underserved farmers, students, adults, and the local farming community near Camden, NJ (Stluka, 2019). Camden is considered a food desert where people have limited access to a variety of healthy and affordable food (Dutko,2012).

Food and Nutrition Insecurity: Increasing food and nutrition education is important because poor nutrition is a leading cause of illness in the United States and is responsible for more than 600,000 deaths per year. The overall diet quality score for Americans is 59 out of 100, indicating that the average American diet does not align with Federal dietary recommendations (USDA, 2022). This program looks to increase food and nutrition education to encourage healthier lifestyle behaviors and choices. According to the USDA, there is a strong association between food insecurity and poor nutrition, with individuals who report being most food insecure also at a higher risk of developing diet related diseases such as obesity, diabetes, and hypertension(2022). The USDA defines food insecurity as a lack of consistent access to enough food for every person in a household to live an active, healthy life (2022). This program intends to increase productivity and food sovereignty*, resulting in more food grown to reduce food insecurity among community members that have been historically underserved and plagued with diet related chronic disease. Ensuring participants have consistent access to readily available and nutritionally adequate safe food, promotes well-being and prevent diseases, particularly among underserved populations (USDA, 2022).

*USDA defines food sovereignty as a community’s ability to restore self-determination over the quantity and quality of the food they eat by controlling how their food is produced and distributed. This creates closed loop, resilient food systems that can sustain communities independently.

Lack of Farm Knowledge: Current farm owners/operators are aging, and new farmers are needed to keep farmland in production and to strengthen the future of the industry. One of the main goals of this program is to increase the number of new farmers and land stewards who promote and practice no-till farming and food sovereignty. Participants will receive farming lessons and experience to learn how to effectively practice no-till farming. According to FoodInsight.org, only 52% of people asked were familiar with sustainable farming, and even fewer were familiar with terms like no-till (19%) (2022). At Tuba we define no-till as leaving the soil mostly undisturbed while improving soil health by leaving disease-free crop residue on the soil as mulch. No-till farming can be a low-cost method to meet food needs without depleting the environment and without fossil fueled machinery. Additionally, participants will learn other sustainable farming lessons, including waste reduction through composting, improving soil health, up-cycling and recycling material, water use efficiency, pest and disease management, seed saving, cover cropping, crop rotation, and more.

Tuba Farm is a 1-acre, solar-powered, no-till market garden located in Glassboro, New Jersey. Founded in 2021 by Cyara Phillips, a Hampton University graduate with decades of nonprofit experience, the farm operates under the Tuba Farm Foundation, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. The foundation is dedicated to promoting food access, reducing waste, and fostering sustainable agricultural practices, particularly in communities within a 20-mile radius of Camden, New Jersey .

Our farm produces a diverse array of vegetables, herbs, and flowers, and practices beekeeping, hydroponic farming, and raises livestock. As part of our land conservation efforts, we are cultivating an orchard for our Food Forest. We distribute our harvests onsite, at local farmers markets, and provide fresh produce free to food pantries in Gloucester and Camden counties .

Tuba Farm operates full-time, with a dedicated team led by founder Cyara Phillips. The farm is equipped with essential resources, including a solar-powered infrastructure and specialized equipment such as tractors, which were integral to the implementation of our recent health and education-focused farming initiative. This initiative engaged participants in at least 2.5 hours of weekly farming or gardening activities, aligning with CDC guidelines for moderate-intensity physical activity, and included educational workshops on nutrition and sustainable agriculture practices .

Our markets include direct-to-consumer sales through a U-Pick model, local farmers markets, and community-supported agriculture (CSA) programs. We also offer donation-based produce, allowing customers to pay what they can, ensuring accessibility for all community members .

Tuba Farm’s commitment to sustainability, community engagement, and education positions us as a vital contributor to the local food system, striving to build a more equitable, resilient, and sustainable food future for all.

Cooperators

- - Technical Advisor

- - Technical Advisor

Research

Program Overview:

A total of four new farmers and two Lead Farmers participated in a 16-20 week health, education, and food access program, which ran from May 18th to September 7th. The program aimed to explore the potential health benefits of no-till farming, as moderate-intensity exercise, and its impact on stress, physical health, and food security. Participants were encouraged to invite friends and family to volunteer, fostering a sense of community involvement.

Program Schedule:

Participants engaged in the program during the following hours:

- Fridays & Mondays: 6:00 PM - 8:30 PM

- Saturdays & Sundays: 8:00 AM - 1:00 PM

Each participant was expected to contribute 2.5 hours per week of no-till farming and complete 1-2 surveys weekly. In addition to physical activity data, participants also spent at least 30 minutes per week completing surveys and providing monthly physical health measurements. These surveys were used to evaluate changes in stress, health knowledge, food access, and overall health perception.

Data Collection and Technology:

To monitor participants' physical activity, the program utilized various technological tools, including fitness trackers/smartwatches. These devices allowed participants to track their steps and overall activity during farming sessions. The goal was to determine whether 2.5 hours of moderate-intensity farming per week could lead to improvements in health outcomes, such as stress levels, VO2 Max, resting heart rate, blood pressure, and average daily steps.

Survey Instruments and Assessments:

Several tools were employed throughout the program to track various outcomes:

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS): Administered multiple times to assess changes in participants' stress levels. Tuba Farm Gardening and Health Assessment: A general program survey given at the beginning and end of the program, which gathered insights on health goals, knowledge, confidence, food education, and access. Farming Quiz: Taken at the start, mid-point, and end of the program to assess participants' knowledge progression about farming practices. Modified USDA Food Security Questionnaire: Used to measure changes in food security as a result of increased access to healthy foods grown at Tuba Farm. Brief Sense of Community Index: Administered to assess whether the farming program enhanced participants' sense of community.

Monitoring and Support:

Lead Farmers played an integral role in the program by checking in with participants weekly, ensuring they met farming hour requirements, and monitoring their survey completion. In addition, a consent form and waiver were provided to all participants by the Lead Farmers and technical advisor before they could begin the program.

Program Evaluation:

At the conclusion of the program, participants completed a Program Satisfaction Survey, which assessed their overall experience and feedback. Results were electronically recorded and can be made available in print upon request.

Additional Measures:

Research Farmers planned to measure # of square feet utilized for this program, # of plants sown, # of eggs collected, pounds of honey collected, # of workshops, # of participants and hours each week, # of rows planted, # of volunteers, # of volunteer hours, # of farm tours, Types of crops, pounds of produce harvested, pounds of produce distributed, pounds of produce each participant harvests and takes during the program.

Template of Brief Sense of Self Community Scale -SARE

Template of General Program Intake Form - SARE

Template of Perceived Stress Questionnaire - Google Forms

Template of Tuba Farm_s Gardening & Health Assessment Tool - SARE

Detailed Discussion of Farm Hours:

The 20-week program began on April 27, 2024, with Participant 3 (P3) adult Female, who was a Master Gardener student for Camden County New Jersey. P3 received one-on-one farm lessons for 3 weeks before all other participants joined on May 18, 2024. This was to assess if an earlier start had any impact amongst the cohorts. We found that P3 starting earlier did not have significant impact in this study. From May 18, 2024, until September 7, 2024, 2 additional new farmers visited Tuba Farm at least once per week to complete 2.5 hours of moderate intensity farming. For 16-20 weeks Lead Farmers (LF) were able to teach no-till, sustainable, and natural farming techniques to research participants 1, 3, and 4. Participants were allowed to fulfill their required 2.5 hours Friday and Monday 6p until 8:30p or Saturday and Sunday 8a until 1p. P3 completed 47.5 farm hours and 21 surveys. Participant 1 (P1), adult Female, completed 40 farm hours and 18 surveys. Participant 4 (P4), adult Female, who is a recent college graduate, completed 30 farm hours and 14 surveys. During this program participants personally introduced 10 volunteers to Tuba Farm, including 7 children and 3 adults, they helped them complete 138 volunteer hours. The result of participants being encouraged to bring friends and family along with them to volunteer had a positive impact on the lead farmers, research participants, other volunteers and farm productivity overall. Participant 2 (P2), adult Female, farmed between May (week 4) and July (week 11) before discontinuing due to health. P2 completed 20 farm hours and 9 surveys.

Detailed Discussion of Surveys

Surveys were used to assess qualitative and quantitative changes in health, confidence, knowledge, and activity. Consent forms and waivers were issued by the technical advisor and Lead Farmers on the first day of participation.

The following surveys were administered throughout the program:

- Perceived Stress Scale (PSS): Given four times to measure stress levels.

- Tuba Farm Gardening and Health Tool: Administered at the beginning and four additional times to track health goals, confidence in knowledge, food consumption, sustainable practices, and food access.

- Farming Quizzes: Conducted three times (beginning, mid-point, and end) to assess knowledge progression.

- Modified USDA Food Security Questionnaire: Administered at the start and end of the program to evaluate food security.

- Brief Sense of Community Index: Taken three times to assess the sense of community and civic engagement.

- Program Satisfaction Survey: Given at the end to capture participant feedback on their experience.

Discussion of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)

The PSS results showed mixed changes in participants’ stress levels:

- P1: Started with a low stress score of 5 and increased slightly to 6 by the end.

- P3: Started with a moderate stress score of 20 and decreased slightly to 17.

- P4: Started with a low stress score of 6 and increased to 10.

Overall, 67% of participants experienced a slight increase in stress by the end of the program, even though they reported feeling that the farm activities helped reduce stress. This could be attributed to the intense labor demands of no-till, sustainable farming, especially during the peak months (June-September). The program provided participants a realistic view of farming's physical demands, which likely contributed to the reported stress increase.

LF experienced increased stressed from the onset of the program until the last farming event in November. This increase in stress correlates to the new farm participants and is reasonably expected due to the grueling demands of the growing season on the farm. No-till sustainable farming using natural methods requires intense labor at times and can cause stress, especially during the peak months of June, July, August and September in zone 7b. This peak timeframe aligns closely with the farm program; intentionally providing new farm participants with the opportunity to experience farming under realistic circumstances. They learned firsthand that farming is not always easy and stress-free. That said, the slight increase in stress reported by participants could be attributed to many unknown factors not directly correlated to the farm. For example, P2 started the program with a Moderate PSS score of 23 and ended the program abruptly with a High PSS score of 35, citing health issues that had no relation to the farm. In the future, we may add a question to the survey asking people to explain any changes in stress they feel.

Discussion of the Tuba Farm Gardening and Health Assessment

Participant P1 and P3 had, a little experience farming or gardening prior to becoming involved at Tuba Farm, while P4 expressed having very little to no experience. All participants, including Lead Farmers, had someone in their household with a chronic health condition. Participants reported several changes in their health behaviors. When asked if farming/gardening at Tuba Farm helps save money on food, 100% of participants, including LF, agree to some level; P1 demonstrated the most change, initially answered "Strongly disagree" but in the last survey reported "Agree".

When asked how often they eat at least one fruit per day, P1 reported "Never"; P3 reported an increase from "Often" to "Everyday"; and P4 reported "Often" and "Sometimes". Further, when asked how often they eat more than one kind of fruit per day, P1 reported "Not Often" and "Never". P3 reported an increase from "Often" to "Everyday" by the end of the program. P4 reported "Sometimes" eating more than one kind of fruit per day. 67% of the new farmers reported eating at least one vegetable per day "Everyday" throughout the program, while 33% reported eating at least one vegetable per day "Often". This same trend was true when asked, "how often do you eat more than one kind of vegetable per day, not including corn or potatoes" and "how often do you eat least 2 or more vegetables as part of your main meal, not including corn or potatoes".

The program successfully encouraged participants to eat more vegetables, though daily fruit consumption was not achieved by all participants, likely due to the farm’s limited fruit production. Tuba Farm's fruiting plants were established in 2021 and had not started to produce an abundance of fruit during this program. Consequently, Tuba Farm's main contribution was large quantities of vegetables, honey, eggs, and flowers during this 20-week program. Fruit was provided by Tuba Farm, but in very limited quantities and on an inconsistent basis.

More details from this assessment can be found in the "Learning Outcomes" section.

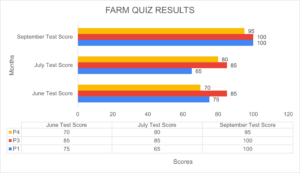

Discussion of the Farm Quiz and Program Satisfaction Survey

All participants showed improved scores on the farming quiz:

- P1: Increased from 75% to 100% correct answers.

- P3: Increased from 85% to 100%.

- P4: Increased from 70% to 95%.

By the end of the program, all participants expressed confidence in growing their own food using sustainable no-till farming practices. They also reported improvements in their health outcomes:

- P1: Experienced increased mobility, ease in squatting, and less fatigue.

- P3: Reported increased vitamin D and improved flexibility.

- P4: Noted improvements in blood pressure and stress relief.

Specifically, P1 expressed experiencing "mobility, ease in squatting, performing, farming/gardening tasks for longer duration, and reduction in overall fatigue". P3 reported an increase in "vitamin D by being outside more, improved flexibility while bending and sitting to pull weeds". P4 reported that the "consistent low impact exercise improved her blood pressure and helped her relieve stress". They reported reduced stress from having the opportunity to commune with nature; focusing on a wide range of farm tasks forced them to stay focused and dismiss distractions; and being in the fresh air while getting exercise helped relieve stress after work.

- 100% of participants confirmed that increasing food and nutrition knowledge resulted in healthier choices.

- 100% agreed that farm training improved knowledge of low-cost, and sustainable agriculture methods.

- 100% confirmed that farm training/workshops increased gardening/farming self-confidence.

- 100% reported growing their own food and increasing access encouraged consumption of fruits and vegetables.

- 100% of the new farming participants confirmed that farming and gardening as a moderate intensity exercise, for at least 2.5 hours weekly, reduced stress.

Furthermore, all farmers, reported that utilizing Tuba Farm as a community gathering space, improved the number and quality of social interactions and civic engagements they had this year. Specifically, P1 "enjoyed learning, working, and sharing as a group and felt it supported the overall learning process." P3 reported meeting a "number of lovely and interesting people through this process and will always cherish my Tuba Sare memories." P4 shared that they were able to "meet other women who are interested in gardening/health and learn from them." She also enjoyed being able to bring friends to the farm to show them something new.

More quantitative details can be found in the "Learning Outcome" section.

Discussion of the Modified USDA Food Security Questionnaire

Food security was assessed using the Modified USDA Food Security Questionnaire:

- P1: Reported low food security, showing a slight improvement by the end (score decreased from 5.24 to 4.47).

- P3: Reported high food security throughout the program.

- P4: Initially reported high food security but showed a slight decline by the end (score increased from 0 to 1.9, indicating marginal food security).

P1 reported Low food security or Food Insecure. Her initial score was 5.24 (Low food security) and she reported an increase in food security during the program, with a lower score of 4.47 (Low food security) by the end of the program. A slight decrease of 0.54 in food insecurity based on the Rasch measurement model. P3 began the program and ended the program reporting high food security with a score of 0. P4 began the program reporting high food security with a score of 0 but ended the program reporting marginal food security with a score of 1.9. Overall, 1 participant had no change in food security, 1 participant had a slight decrease in food security, and 1 participant had a slight increase in food security.

Discussion of the Brief Sense of Community Index

Participants reported feeling more connected to their community through their involvement at Tuba Farm:

- 100% of participants agreed that they felt their needs were being met in the neighborhood and felt connected to the community.

- However, they felt neutral about their influence within the neighborhood and the strength of bonds with others. This may be due to the program’s preplanned structure, which limited participants’ ability to influence the program or engage in broader neighborhood initiatives.

By the end of the program all participants agreed that: "I can get what I need in this neighborhood."; "This neighborhood helps me fulfill my needs."; "I feel like a member of this neighborhood."; and " I feel connected to this neighborhood." Throughout the program, all participants reported strongly agree when asked if they belong in this neighborhood. However, participants felt neutral when asked if they had a say about what went on in this neighborhood or if they had a good bond with others in this neighborhood. These two conclusions are reasonable, because this project was preplanned for participants prior to their involvement and did not allow for their input as far as structure or lessons. Additionally, the time spent was limited to farm training, education and community engagement, rather than bonding, per se. Additionally, participants reported a neutral response when asked if "People in this neighborhood are good at influencing each other." This program did not allow for influence between new farmers, as Lead Farmers controlled all lessons and activities as the primary influence for all participants. Overall, participants reported agree and strongly agree to 5 of 8 or 63% of questions asked on the "brief sense of community index” survey, indicating that utilizing Tuba Farm as a community gathering space, improved participants sense of community. Specifically, they agreed their needs were fulfilled and strongly agreed to feeling connected as group members.

Detailed Discussion of Health Metrics

We tracked health outcomes using various measures, including blood pressure, resting heart rate, and VO2 max. Additionally, participants wore fitness trackers to monitor average daily steps.

Blood Pressure and Resting Heart Rate

- P1: Initially had elevated blood pressure (149/98) but showed improvement throughout the program, with a final average of 133/77.

- P3: Maintained stable blood pressure and heart rate, showing no significant changes.

- P4: Showed a downward trend in blood pressure from 140/94 to 108/65, indicating improvement with consistent activity.

P1 had an initial B/P of 149/98, systolic B/P(SBP) which was elevated, this could mean participant was hypertensive, heart rate (HR) was 63 which is within normal limits (WNL). Vitals were measured prior to farm activity, no food/drinks consumed. B/P had a downward trend with consistent activity, average SBP over the remaining sessions was 133, diastolic and heart rates were 77 and 73, which were higher than initial reading but still WNL.

P3 had an initial B/P of 129/75, HR 81, which is WNL. Vitals were measured prior to farm activity, no food/drinks consumed. B/P remained consistent, while HR #2 was 91, remaining heart rates appeared to stabilize with a downward trend at 77,76,74 with consistent activity, all were WNL.

P4 had an initial B/P of 140/94, which was on the borderline of high blood pressure, HR 64, WNL. Vitals were measured prior to farm activity, but participant reported having food and coffee prior to measurement. Remaining blood pressure measurements were on a downward trend with consistent activity-#2 130/86, #3 122/75, #4 108/65, all WNL. Heart rates were all WNL at 89, 73, 80.

VO2 Max

- P1 showed slight improvement, moving from an average VO2 max of 26-30 to 27-31, demonstrating an increase in cardiovascular fitness.

- P3 and P4 did not show measurable improvements due to inconsistent tracking data.

VO2 Max reflects the maximum amount of oxygen the body utilizes during exercise. Higher levels of VO2 Max indicates a higher level of cardio fitness and endurance. Below average levels of fitness are associated with long term risks to health. In this case, we found that 1 participant had below average cardio fitness for her age, 1 participant had fair to average cardio fitness for her age, 1 participant had average to good cardio fitness for her age. Both P1 and 1 Lead Farmer demonstrated slight improvement in cardio fitness as reported by increased VO2 Max ratings during this program. This study utilized Fitbit and Apple fitness tracker/smartwatch to encourage participants to monitor their activity while farming voluntarily. Apple's fitness tracker did not accurately track VO2 max for P4 but did for 1 Lead Farmer, Fitbit did track for P1 but not P3. P1 experienced a V02 Max that averaged between 26 and 30 June through September, with a slight increase of average V02 max to 27-31 for April and May which coincide with the beginning of this program. She demonstrated average to good cardio fitness for women her age. P3 experienced a V02 Max that averaged between 25 and 29 during the program but Fitbit failed to collect monthly data; therefore, an assessment of cardio fitness using this measure was not made. P3 demonstrated fair to average cardio fitness for women her age. P4 experienced a V02 Max that averaged 30.5 June through September, showing below average cardio fitness for women her age but Apple watch failed to collect monthly data; therefore, an assessment of cardio fitness using this measure was not made. 1 LF, a Female, experienced a V02 Max of between 29.1 in March and 30.8 in September, demonstrating an increase in VO2 Max during the program and an above average V02 Max by the end of the program.

Average Daily Steps

All participants demonstrated significant increases in average daily steps (ADS):

- P1: Increased from 415 steps to 4,042 steps (an 874% increase).

- P3: Increased from 1,388 steps to 5,478 steps (a 295% increase).

- P4: Increased from 1,798 steps to 3,211 steps (a 79% increase).

New farmers experienced significant increases in average daily steps (ADS) taken as reported by their fitness watches. P1 reported ADS of 415 steps in April prior to beginning her farm training on May 18, 2024. P1 reported an increase in ADS of 4042 in September, an increase of 3,627 steps or an 874% increase. P3 reported ADS of 1,388 in April of 2024 and 5,478 in September, which is an increase of 4,090 steps or 295% increase. A less significant increase was seen for P4, who had 1,798 ADS in April prior to beginning the program and had 3,211 ADS in September. P4 demonstrated an increase of 1,413 ADS or a 79% increase.

Additional Measures

During this program, participants helped plant approx. 3000 square feet (sq. ft.), which included 1000 sq. ft of raised beds, 1000 sq. ft in a greenhouse, 1000 sq. ft in the food forest and pollinators garden. New farmers helped plant the following crops: Asian greens, arugula, mizuna, radish, beets, carrots, Swiss chard, ground cherries, sweet peas, green beans, edamame, Pac choi, cabbage, kale, peppers, tomatoes, okra, cucumbers, watermelon, flowers, blackberry bushes, sunchokes, Brussel sprouts, herbs, spinach, and broccoli. Throughout the season the participants helped harvest and distribute approximately 3800 pounds of produce. We intended to track the # of plants sown, # of eggs collected, pounds of honey collected, pounds of produce each participant harvests/takes during the program; however, as the program took place this was too much data for the Lead Farmers and new farm participants to collect in addition to the hands-on farming, workshops, and surveys. Tracking this additional information would have required far more hours than allotted for this program and the labor required to fulfill this was not feasible without undue burden. Therefore, we used averages in some instances and approximate numbers when reasonable.

Impact of Farming and Gardening on Health Outcomes:

The results of this study indicate that farming and gardening as a moderate-intensity exercise, conducted for at least 2.5 hours per week, positively impacted participants' health outcomes, as evidenced by both qualitative and quantitative findings.

Farm Hours and Health Metrics: Throughout the program, participants collectively contributed 138 hours of farming and completed 62 surveys. Farming as a moderate-intensity exercise led to notable improvements in several key health metrics, including resting heart rate, blood pressure, and VO2 Max. Additionally, the program successfully encouraged significant increases in participants' average daily steps.

-

Resting Heart Rate and Blood Pressure: 67% of participants experienced a reduction in blood pressure, demonstrating a downward trend with consistent farming activity. While all participants maintained resting heart rates within normal limits, 33% showed a slight decrease in resting heart rate over the course of the program.

-

VO2 Max: Both Participant 1 (P1) and 1 Lead Farmer 1 demonstrated slight improvements in cardio fitness, as indicated by increased VO2 Max readings, reflecting better cardiovascular endurance as a result of the farming activities.

-

Daily Steps: All three participants exhibited significant increases in their average daily steps as tracked by fitness watches. P1 reported an 874% increase in daily steps, P3 saw a 295% increase, and P4 had a 79% increase, further supporting the health benefits of consistent moderate-intensity exercise through farming.

Survey Findings and Qualitative Health Outcomes:

While farming did not result in a quantitative reduction in stress levels, the qualitative data suggests that participants experienced a reduction in perceived stress. Lead Farmers, despite experiencing increased stress from the demands of the program, reported lower stress levels compared to previous years, due in part to the support and volunteer help provided by the new farm participants. The encouragement for participants to involve family and friends in the program had a positive impact on farm productivity, team morale, and stress reduction.

-

Farming Knowledge and Confidence: Farming quiz results demonstrated an increase in knowledge for all participants by the end of the program, highlighting the effectiveness of hands-on training and educational materials. Participants also reported that their increased food and nutrition knowledge led to healthier dietary choices, with a significant increase in vegetable consumption.

-

Sustainable Agriculture and Self-Confidence: All participants agreed that farm training enhanced their understanding of sustainable, low-cost agricultural practices. The program also significantly boosted participants' self-confidence in gardening and farming skills, particularly in growing their own food, which in turn led to greater access to fresh vegetables.

-

Food Security: Regarding food security, one participant reported no change, while another had a slight decrease, and one participant experienced a slight increase in food security, indicating a varied impact across the cohort.

-

Sense of Community: The program facilitated increased social interactions and civic engagement, with participants expressing a stronger sense of community. The “Brief Sense of Community Index” survey revealed that participants agreed or strongly agreed with statements suggesting an improved sense of belonging and connection within the community fostered by Tuba Farm.

Conclusion:

The program's overall impact on health was positive, with significant improvements in physical activity, farming knowledge, and community engagement. The marked increase in average daily steps directly correlated with improved health metrics for all participants. Additionally, while the program did not show a measurable reduction in stress through quantitative data, the qualitative feedback indicates that participants experienced a reduction in stress, reinforcing the value of farming as a therapeutic and health-promoting activity. These findings underscore the potential of farming and gardening as a sustainable form of exercise and community-building practice, contributing to both physical health and overall well-being.

Education & outreach activities and participation summary

Participation summary:

Education & Outreach Activities and Participation Summary:

Tuba Farm facilitated a variety of educational and community-building activities throughout the program, engaging participants with hands-on farming experiences, local agriculture educators, and service providers. These activities were designed to foster learning, build connections, and promote community engagement in sustainable farming practices.

On-Farm Demonstrations & Workshops:

The farm hosted 32 on-farm demonstrations, offering participants the opportunity to engage in various farming practices. These sessions, ranging from 2.5 to 3 hours, covered a wide range of activities, including but not limited to seed starting, no-till farming techniques, composting, irrigation installation, pest scouting, cover cropping, and harvesting. Participants also learned to operate farm machinery, plant native species, care for bees, and practice food preservation and bouquet building. These hands-on experiences not only taught essential farming skills but also empowered participants with practical knowledge they could apply at home and in their communities.

In addition, 17 workshops and field days were held, incorporating both educational and recreational elements. Notable events included Earth Day and Arbor Day tree plantings, Mommy and Me Yoga, Juneteenth Yoga at Tuba Farm, and a Sip and Seed event. Participants also took part in community initiatives such as 5 Volunteer Days, where they planted native species in the pollinator garden, established a hedgerow, and helped set up irrigation systems for the farm and community garden plots. During these volunteer days, participants also learned to make natural fertilizers, start seeds, harvest crops, and scout for pests.

As part of our outreach efforts, 5 Community Feeds were held in Camden, NJ, where participants donated time and resources to distribute meals to residents in the food desert. This initiative helped to strengthen community ties and promote food access in an area with limited resources.

Farm Tours & Collaborative Events:

Participants also assisted with 3 farm tours, providing visitors with insights into the farm's operations and sustainable practices. Notable tours included a special World Bee Day tour of the apiary, a collaborative tour with partners from Pineland Preservation Alliance and Roots to Prevention, and a Farmsgiving event during the November community feed. During the Farmsgiving tour, participants guided community members through the farm, explaining crop choices and offering guidance on selecting produce for the meal.

Interest Meetings & Program Outreach:

Two interest meetings were held to introduce the program to prospective participants and stakeholders, including board members and advisors. These virtual sessions outlined the program’s goals, expectations, and eligibility criteria. As a result, four participants were selected to join the program after attending one or both of these sessions.

Participants were also introduced to a wellness initiative through the Coalition for Food and Health Equity (CFHE), where they received free Fitbits at Tuba Farm. The program tracked their health progress, although no information was shared between the two programs to maintain privacy.

"Be Leaf in Yourself" Virtual Presentation:

Each participant participated in the "Be Leaf in Yourself" virtual presentation, an introductory session aimed at boosting confidence in beginning growers. The presentation covered essential topics such as the L.A.W.S. (Life, Air, Water, Soil) of plants, seed starting techniques, and plant care, ensuring that all participants were well-equipped to begin their farming/gardening journey at Tuba Farm.

Overall, these diverse educational activities fostered both personal growth and community engagement, helping participants develop valuable skills in sustainable farming while contributing to local food security and community wellness.

Learning Outcomes

Learning Outcomes Summary:

Throughout the 20-week program, participants were assessed using a "Farm Quiz" administered three times. The quiz, consisting of 20 questions focused on no-till, natural farming, was designed to evaluate participants' comprehension of the material taught through onsite training and weekly reading assignments. Participants were instructed not to use any external sources to complete the quizzes. Reading materials were provided electronically each week, up to week 19 of the program. Each quiz drew on the previous week’s content, with the goal that by the end of the program, participants would have learned the correct answers to all quiz questions. In the final week, participants completed their final farm quiz, which included both quantitative questions and additional qualitative questions aimed at gauging participant satisfaction and learning experiences.

All participants demonstrated improvements in their farm knowledge, as indicated by their increasing quiz scores. P1’s quiz scores rose from 75% to 100%, P3’s increased from 85% to 100%, and P4’s scores went from 70% to 95%. It is noteworthy that P3, being a Master Gardener student, had a higher initial score due to prior agricultural knowledge, which likely contributed to a more advanced starting point. P2 took the quiz once before leaving the program, scoring 70%.

In addition to the quantitative improvement in quiz scores, all participants reported significant changes in knowledge, attitude, skills, and awareness, as reflected in the qualitative responses on the final quiz. When asked whether increased food and nutrition knowledge led to healthier choices, P4 shared that before joining the program, they rarely ate salads or raw vegetables, but now, picking food they helped grow motivated them to try and enjoy new vegetables. P1 emphasized the increased diversity of fruits, vegetables, and herbs used in their household, noting a significant rise in frequency and creativity when incorporating these into meals. P3 noted a shift in their perspective on conventional produce, stating, “Being involved in the farming process caused me to reflect on how conventional produce is grown and the lack of nutrients therein.”

Knowledge of Sustainable and Low-Cost Agriculture:

All participants reported increased knowledge of low-cost and sustainable farming methods. They became familiar with techniques such as seed harvesting for future seasons, creating homemade fertilizers and compost, and applying no-till practices. P3 remarked on how previously unfamiliar they were with homemade fertilizers and pesticides, but the hands-on experience at the farm made them realize how simple and effective these methods are for their own gardening practices.

Increased Confidence in Farming/Gardening Skills:

When asked whether farm training and workshops increased their self-confidence in gardening and farming, every participant affirmed that they felt more confident in their ability to start growing their own food. The hands-on approach, which allowed them to apply the knowledge they gained each week, was crucial to building this confidence. P3 highlighted that while reading was essential, the opportunity to implement and experience farming firsthand helped them achieve a deeper understanding.

All participants, including the Lead Farmers, reported that growing their own food and increasing access to fresh produce positively impacted their consumption of fruits and vegetables. P1 shared that while their personal garden had mixed success, the consistent training and applied learning created a stronger focus on vegetables in their household, even when purchasing produce from the store. P3 noted that access to farm-fresh produce made them more creative in incorporating it into their meals, and P4 expressed enthusiasm for eating fresh food they had personally harvested, even trying vegetables they previously disliked.

The Lead Farmers, too, were encouraged to consume more fruits and vegetables to minimize waste, and the increased productivity resulting from the additional farming help provided by participants led to larger harvests for the community.

Changes in Eating Habits and Health Consciousness:

Participants were also regularly assessed using Tuba Farm’s Gardening and Health Assessment Tool, which gathered data on changes in knowledge, attitudes, skills, and eating behaviors. When asked about changes in their eating habits, P1 reported becoming more intentional about vegetable intake, including having more vegetables at home and consuming them more frequently. P3 noted a significant increase in the variety of leafy greens they tried and reported enjoying eating raw vegetables, often incorporating them into salads. Similarly, P4 stated that since starting the program, they were eating more salads and raw vegetables, making them a regular snack option.

67% of participants reported improvements in their eating habits when asked to rate the healthiness of their diet. Both P1 and P4 began the program rating their habits as “Fair,” but by the end, they both rated their habits as “Good.”

Increased Confidence in Farming Techniques:

When asked about their confidence in no-till and sustainable farming, 67% of participants reported a boost in confidence regarding their knowledge in these areas. Notably, P1 went from being uncertain (“Maybe”) to feeling confident (“Yes”) by the end of the program. Every participant reported increased confidence in preparing soil and planting seeds or young plants for their garden plots, with P1 showing the most significant improvement from “Fairly Confident” to “Very Confident.” Additionally, 67% of participants reported increased confidence in their ability to choose appropriate plant or seed varieties for their garden, with P1 showing the most substantial improvement, going from “Not at all confident” to “Very Confident.”

67% of participants expressed feeling “Very Confident” in their ability to weed, water, and maintain their garden plots by the program’s conclusion. Similarly, when asked about harvesting and utilizing their crops, 67% of participants reported increased confidence in these tasks. P1 started the program feeling “Not at all confident” in solving garden problems but ended the program feeling “Fairly confident,” showing the gradual but consistent increase in confidence observed across all participants.

Composting Habits:

Another area of improvement was composting habits. All participants reported an increase in composting during the program. P1, who initially composted “Sometimes,” reported composting “Almost Always” by the end. P3, who started composting “Never,” also moved to “Almost Always,” while P4 increased their composting from “Rarely” to “Sometimes.”

Lead Farmers' Development:

The Lead Farmers also experienced personal growth in their teaching and leadership abilities. Through their role in developing learning materials, administering surveys, and adjusting lessons to meet the needs of participants, they became more skilled in teaching sustainable, no-till farming methods. They reported a significant increase in their confidence in educating new farmers and acknowledged the benefits of having additional apprentices and volunteers to boost productivity. This increased capacity allowed them to plant and harvest more produce, benefiting both the participants and the broader community.

Note on Participant P2:

While P2 showed some improvement in knowledge, confidence, and farming practices, they did not complete the surveys, readings, or onsite lessons required for full program participation. As such, their results are not included in this cohort analysis.

Project Outcomes

Farming has always been a blend of both rewarding and stressful work for us as Lead Farmers. We love growing food in a natural and sustainable way, but during peak season, the demands can feel overwhelming. To help manage the stress and make farming more enjoyable, we created this program to bring in more help and lighten the load. Our goal was simple: to create a mutually beneficial program that would reduce our stress while increasing productivity. Looking back, we’re proud to say that we achieved that goal.

The support we received from the new farmers and volunteers was invaluable. Tasks that would normally take us days or even weeks to complete were done in hours, thanks to their consistent hands-on participation. The plants thrived from the extra care and attention they received, and in some cases, we had to terminate cucumber and tomato crops because they were growing so vigorously. The joy we felt from the constant interaction with the new farmers and volunteers was a huge source of motivation, and it kept us energized throughout the season. There were days when the new farmers arrived on the farm before we had even gotten dressed! They were incredibly dedicated, often telling us how impactful our teaching had been to them. We’re proud to say that many of them continue to stay in touch, and we’ve built lasting relationships with them. We feel strongly about their future in farming.

It was deeply satisfying to see how much the participants appreciated the produce we grew. Their feedback about the taste and quality was overwhelmingly positive throughout the program. The constant harvesting kept us on track with our goal of minimizing waste. With the participants’ help, we had far less produce to compost in 2024, as they consumed it enthusiastically. In fact, all of the participants rated the program a perfect 10 out of 10 and could not find any negatives. This feedback made us feel accomplished and validated in our efforts.

Here’s some of the feedback from the 3 NEW FARMERS we trained:

"I very much enjoyed learning, working, and sharing as a group, and felt it supported the overall learning process."

Positive aspects of the program included: "Hands-on learning, seeing the growth of items planted on the farm, diversity of activities, farming teamwork, interactive 'table talks' to share learning, and exposure to a variety of fruits, vegetables, herbs, and flowers."

"The program was great! I believe that it’s beneficial because of the hands-on experience and practical knowledge that can be utilized by growers with a wide variety of experience levels."

"I am very grateful for this program and everything I was able to learn. I really hope the program continues in the future so that more people can gain knowledge and help grow healthy food to feed themselves and their community."

This feedback, along with the growth we’ve seen in both the participants and the farm, reinforces the importance of what we’ve built here. We’re excited for the future and the positive impact this program continues to have on all involved.

P1-Sare Final Farm Quiz P3 Sare Final Farm Quiz P4 Sare final quiz

Overall, we are pleased with the results of this project, which demonstrated positive outcomes. However, upon reflection, we see areas where we could make adjustments to further enhance the health benefits for participants. One key takeaway is that substantial increases in walking appeared to have a significant impact on participants' health, particularly in terms of improving blood pressure. At some point during the program, most participants were able to increase their daily step count to 5,000 steps on average. Moving forward, we would consider incorporating a weekly target of 10,000 steps at the farm as a program requirement, though we would ensure that there is no penalty for participants who are unable to meet this target. This change could help boost physical activity levels and improve health outcomes even further.

Regarding stress, we believe adding a more nuanced approach to the stress survey could provide deeper insights into the factors contributing to changes in stress levels. Specifically, we would include a question asking participants to distinguish whether their stress increase or decrease was related to farming activities or personal life. This additional question would allow us to better understand if the farming program itself was a source of stress, and if so, how we could adapt the program to help mitigate those effects. If we identify farming activities as a stressor, we will explore strategies within the program to address and reduce that stress.

In terms of tracking and measuring participant progress, we were unable to fully quantify each individual’s harvest during the program due to time constraints. In future iterations, we would provide participants with journals to track their activities and accomplishments throughout their time on the farm. These journals would give participants the opportunity to reflect on their personal growth and document the results of their hard work, which could be valuable both for them and for assessing the program's impact.

In sum, we successfully met our farming objectives by leveraging the help of new farmers and volunteers, which not only increased productivity but also alleviated some of the stress associated with farming. We also achieved our program goals of measuring whether engaging in 2.5 hours of moderate-intensity farming activity per week could positively affect health, food access, and knowledge. Going forward, we plan to continue encouraging community members to participate in consistent farming activities, with the overarching goal of improving health, food security, and agricultural knowledge.

We believe that the insights and lessons learned from this program will be valuable to a broad range of individuals and groups. This report has broad applications and could benefit a variety of stakeholders. Public health agencies and health educators could use the findings to integrate farming into community health programs, promoting physical activity and improving health outcomes, particularly in underserved areas. Nonprofit organizations focused on food security could use the insights to design programs that combine food access with health and wellness initiatives. Community centers and local government agencies might apply the findings to enhance local health and wellness initiatives by encouraging farming participation.

Educational institutions, from schools to universities, could incorporate these findings into curricula or after-school programs, providing hands-on learning experiences in agriculture, health, and sustainability. Environmental advocacy groups focused on sustainability could advocate for farming as a practice that contributes to climate resilience and local food systems. Farmers and agricultural cooperatives could adopt similar models to engage volunteers, reduce burnout, and improve productivity on farms.

Workplace wellness programs might find value in integrating farming activities to reduce stress and promote physical well-being among employees. Researchers in public health, agriculture, and social sciences could use the data for further studies on the health benefits of farming and its impact on community dynamics. Wellness and mental health professionals might incorporate farming as a therapeutic practice for stress reduction and mental well-being.

Fitness and outdoor activity advocates could promote farming as a form of "green exercise," and volunteer organizations might use the report’s model to enhance engagement and retention. Finally, policymakers and urban planners could apply the findings to inform land use, urban farming, and food access policies, using farming as a tool to promote community health and sustainability.

Whether they are located locally or in different regions, these stakeholders can benefit from understanding the potential of farming as a tool for improving health, food access, and community engagement.

Information Products

- Closing the Loop Sustainably

- The Pros and Cons of Sustainable and Organic Farming

- Organic versus Conventional Farming

- Benefits of Organic or Natural Farming as experienced by Tuba Farms

- Natural Weed Management Strategies

- Improving Soil Health Using Low-Cost Natural Methods

- Creating Natural Sustainable Fertilizers

- Pest Management Strategies and No-Till Farming

- Managing Diseases in Natural No-Till Farming

- Crop Rotation and Companion Planting as IPM

- Enhancing Soil with Beneficial Bacteria

- Measuring Nutrient Density using Brix

- Sustainable Watering Methods

- Farm Quiz and Satisfaction Survey