Final report for GNC15-201

Project Information

Tall fescue (Schedonorus arundinaceus, syn. Festuca arundenacea, syn. Schedonorus phoenix) is an invasive grass with known negative effects on cattle health and hypothesized negative effects on ecological communities. Our project addresses these effects by examining the interrelated agricultural, ecological, and social dynamics of tall fescue in working Midwestern grasslands. Our goals were to evaluate (1) use of tall fescue by grazing cattle, (2) avian and arthropod community response to experimental changes in tall fescue cover, and (3) landowner capacity to remove tall fescue on private lands.

Our study was conducted in the Grand River Grasslands of Ringgold County, Iowa and Harrison County, Missouri. This research has been ongoing since 2006, and the current SARE project utilizes both prior data and new data. Our first field season for this project took place May-Aug. 2016. During the field season, we collected data on cattle grazing preferences in response to tall fescue abundance (Goal 1). Results on foraging preferences demonstrated the potential economic benefits of tall fescue control for farmers. We also counted grassland birds, monitored nests of a grassland bird of conservation concern (dickcissel, Spiza americana), and collected arthropods on all study sites in order to elucidate the costs and benefits for wildlife of removing tall fescue (Goal 2). We also designed and mailed surveys to examine landowner willingness to remove tall fescue on their land (Goal 3). Results from the survey revealed barriers and opportunities for controlling tall fescue on private land.

This project was inspired in part by concurrent research completed by project participants S. Maresh Nelson, J. Coon, and J. Miller on the complex impacts of invasive plants on birds:

Nelson, SB, JJ Coon, CJ Duchardt, JD Fischer, SJ Halsey, AJ Kranz, CM Parker, SC Schneider, TM Swartz, JR Miller. 2017. Patterns and mechanisms of invasive plant impacts on North American birds: a systematic review. Biological Invasions, 19(5): 1547-1563. Link.

Research Conclusions:

Using combined agricultural, ecological, and social approaches to explore invasive grass management has allowed us to identify synergies between agricultural and conservation goals. For example, we found that cattle restrict grazing on tall fescue when other forages are available, especially legumes. We also found that tall fescue reduced the nest survival of a grassland bird. These results indicate that there may be social-ecological co-benefits resulting from reducing tall fescue on pastures. In addition, we found that landowner decisions to manage non-native grasses are driven by social norms, access to resources, and personal norms related to a sense of personal responsibility or stewardship. We also found that controlling fescue using herbicide affects grassland bird species differently, with some sensitive species experiencing reductions in abundance one-year after herbicide application. Based on these results, we advise that landowners who wish to improve forage quality and increase habitat quality consider reducing fescue and other non-native plants in smaller patches to give refuge to those bird species while treated areas recover. In addition, given the potential for personal norms and stewardship values to influence behaviors related to invasive species, managers and researchers could use messaging that reinforces landowners’ existing sense of moral responsibility, reminding them that removing non-native grasses can help wildlife, cattle production, and scenic value in their communities.

Recommendations based on our results have been provided to managers, landowners, and researchers working in the Grand River Grasslands via numerous presentations at both academic conferences and landowner/agency meetings. We have also published several articles and a technical report that have been distributed to interested parties working in the study region and similar working landscapes, all of which are available online.

Agricultural

- Improve understanding of relationships between tall fescue and cattle foraging

Ecological:

- Improve understanding of the impact of tall fescue abundance on ecological communities

- Improve understanding of the impact of tall fescue removal on ecological communities

Social:

- Understand potential barriers to and opportunities for invasive grass removal

- Longitudinal analysis showing change in attitudes (2007-2017)

- Enhance knowledge in the community about invasive species

Outreach:

- Increase interest in sustainable agriculture in a grassland context

- Increase literacy in areas of grassland ecology

Cooperators

- (Researcher)

- (Educator and Researcher)

- (Educator)

- (Researcher)

Research

Agricultural Methods: Within four pastures in the Grand River Grasslands, we examined grazing selectivity by cattle among five forage categories: tall fescue, other cool-season grasses, native warm-season grasses, legumes, and non-leguminous forbs. Since 2007, the four pastures have been managed using patch-burn grazing, a system in which each pasture is delineated into three ‘patches’ of approximately equal size. One patch per pasture is burned in late March or early April on a rotating basis, such that the entire pasture is burned over three-year cycles. A herd of either black Angus or mixed black Angus and Charolais beef cattle had free access to all patches.

All data were collected over two sampling rounds between June and August 2016. In each sampling round, we collected data on forage abundance and use by cattle within 0.1-m2 plots (interior dimensions: 25 x 40 cm). We placed five plots in each patch of each pasture per sampling round (three patches per pasture), thereby sampling a total of 45 plots in the first round and 30 plots in the second. We used a modified version of the point-quadrat method to measure the relative abundance of plants in the five forage categories.

Plots were marked with gridlines creating 25 evenly-spaced grid points. We laid the plot flat on the soil surface, placed a 2-mm-diameter pin in the ground at each of these 25 grid points, and classified the plant rooted nearest to each pin-drop into one of these categories. Within each plot, we calculated the relative abundance of plants in each of the five forage categories as the proportion of all classified plants belonging to each category (i.e., number of plants of each forage type / 25). We then calculated pasture-scale relative abundance of each category as the average relative abundance per category across all plots in a given pasture.

In addition to measuring relative forage abundances, we estimated overall forage use and use of each forage category in each plot. To measure overall forage use, we randomly selected 10 of the 25 grid points per plot (two in each of the five rows of five grid-points) and noted whether the plant rooted nearest to each chosen point had been grazed. To determine this, we examined all shoots on those plants (or all leaves, on plants forming a leaf rosette). If at least two shoots (or leaves) on a given plant were sheared in a straight line, we counted the plant as grazed. We set the threshold at two shoots to reduce the likelihood of false positives (i.e., a shoot appeared grazed but was instead damaged by another cause). If a plant only formed one shoot, as is true of many forbs, we considered it grazed if that shoot was sheared. We calculated overall forage use in each plot as the number of grazed plants divided by 10.

We then measured use of each forage category in each plot. At the same 10 grid points as above, we examined the nearest-rooted plant belonging to each of the five forage categories and documented whether those plants had been grazed. Thus, in every plot we determined the grazing status of up to 10 tall fescue plants, 10 non-fescue cool-season grasses, 10 warm-season grasses, 10 legumes, and 10 non-leguminous forbs. We calculated use of the five forages in each plot as the number of plants in a given category that were grazed divided by the number of plants in that category assessed for grazing (10, if there were at least 10 plants of that category in the plot).

Finally, we quantified use of each forage category by cattle at pasture scale. First, for each category in each pasture we summed the number of plants grazed across all plots to determine total use of each category. We then summed these forage-specific use levels to calculate the total number of plants grazed per pasture (across all categories). Lastly, we divided each forage-specific use level by the total number of plants grazed per pasture to quantify the proportion of all grazed vegetation constituted by each forage category. These values do not refer to biomass consumed, but rather to the proportion of individual plants grazed. We also point out that our measurements of forage use at both spatial scales are not estimates of use by individual animals, but rather of use by the entire cattle herd stocked on each pasture.

Ecological Methods: To determine the impact of tall fescue and tall fescue control on grassland avian communities, we measured avian diversity and relative abundance along survey transects at 18-20 pastures each summer (2015-2018). Several of these pastures (N=8) were treated with experimental tall fescue removal beginning in fall 2014. Each pasture was divided into three ‘patches’, with one-third sprayed with herbicide and seeded with native plant species, one third sprayed and not seeded, and one third untreated (control). Avian measurements are comprised of 3-8 line transects per pasture (depending on pasture size) surveyed 6-10 times from May through August. Between 05:00 and 10:00 on clear days with winds <10 mph, a trained observer walked along the transects, recording all birds within 50 m. Birds in groups >3 will not be counted to exclude the effects of flocking.

In addition to evaluating the grassland bird community, we also monitored nests of dickcissels. From 2013-2016, we searched for nests using behavior of parents (e.g., chipping, provisioning, carrying nesting material) or by flushing parents off their nests at 6-9 sites/year. Each nest was checked every 1-3 days, and we recorded fate (fledge/fail) and measured vegetation within 5 m of each nest. Several of these sites were also included in the tall fescue removal experiment (N=4).

To determine the impact of tall fescue and tall fescue control on arthropod communities, we used a modified leaf blower and a sweep net to sample arthropods along 50-m line transects 20 m away from and parallel to the avian transects (2015-2017). We moved along the transects sweeping the vacuum in a 1-m swath (50 swaths/transect). Arthropod sampling occurred in each of two rounds (June and July) in each patch, and specimens were identified to taxonomic order or family. We calculated abundance and biomass and used regression to test whether abundance and biomass per order are impacted (positively or negatively) by tall fescue abundance or removal.

Social Methods: The 2017 survey conducted as a part of this SARE project was a partial replication of a survey conducted in the Grand River Grasslands region in 2007, with the survey instrument including replicated questions about livelihoods, biodiversity, demographics, and use of grassland management techniques. New items measured attitudes toward invasive and non-native plants, native wildlife, and factors related to grassland management using prescribed fire, grazing, and herbicide. The 2017 survey instrument was pilot tested by cattle producers in Nebraska (N=8). Cattle producers were asked to evaluate the survey instrument on formatting/readability, content relevance, and clarity of the vocabulary. This pilot test resulted in small changes to language and formatting. The Institutional Review Boards from collaborating institutions, the University of Illinois and Iowa State University, reviewed the instrument and survey protocol and approved the use of human subjects [IRB #16389].

To collect survey responses, we used a multiple contact system with reminders for non-respondents to obtain the highest response rate possible. In addition to the mail-back survey, an online survey was offered as a convenient option to complete the survey. In February 2017, 528 landowners were first contacted with a mail postcard that alerted them, “Survey Coming!” The postcard provided brief information about the purpose of the study and a link where they could take an online version of the survey. At two-week intervals, landowners were contacted again and encouraged to complete the survey, for a total of seven possible contacts (waves) per household. Respondents were also offered the option to complete an electronic survey using the online survey platform, Qualtrics. For the seventh wave, any non-respondents with publicly available phone numbers were called as a final reminder.

Of the 528 households sent the first wave postcard, 72 were found to be vacant, not deliverable as addressed, or the addressee was no longer at that address, yielding 456 valid addresses for the following four survey waves. To assess nonresponse bias, during reminder phone calls (N=154), we asked individuals who declined to return a survey basic questions (age, gender, number of acres owned, years of land ownership in Ringgold/Harrison counties). These answers, in combination with census data (demographics) and information from county plat maps (number of acres owned), were used to test whether this sample accurately represented the human population living in and around the Grand River Grasslands.

Over the course of five mailings and one phone call, 32.7% returned the survey (N=149). An additional 3% (N=13) of the total sample answered basic questions over the phone. These served to help us assess non-response bias, defined as a difference between those that turned in the survey and those that did not that affects interpretation of results. Our evaluation of the non-response bias found there was no detectable differences in age between the two groups. Furthermore, an increase in age between the 2007 sample (average 62) and the 2017 sample (average 67) is likely reflecting a broader pattern of aging farm operators in Iowa. The gender composition in the 2017 sample is similar to that of the 2007 sample. Based on this, we believe that non-response bias is not a concerning issue and that our sample accurately reflects GRG landowners.

Agricultural Objective 1: Improved understanding of relationships between tall fescue and cattle foraging

The goal of these analyses was to determine how the relative abundance of several vegetation types influences grazing pressure and selectivity. We built generalized linear mixed models (lognormal distribution and identity link, study site as random variable) using the relative abundances of tall fescue, warm-season grasses, cool-season grasses, forbs, and legumes as predictor variables, alongside additional predictor variables such as time-since-fire, sampling round, and sampling date. We were particularly interested in how these predictor variables influenced (1) total grazing pressure across all vegetation types within sampling plots, and (2) grazing pressure specifically on tall fescue, so we conducted separate analyses for each of these two response variables. For each analysis, we constructed a candidate model set of predictor variables potentially explaining grazing pressure and then used an information theoretic approach (Akaike’s Information Criterion corrected for small sample sizes, AICc) to compare the relative fit of candidate models within each set.

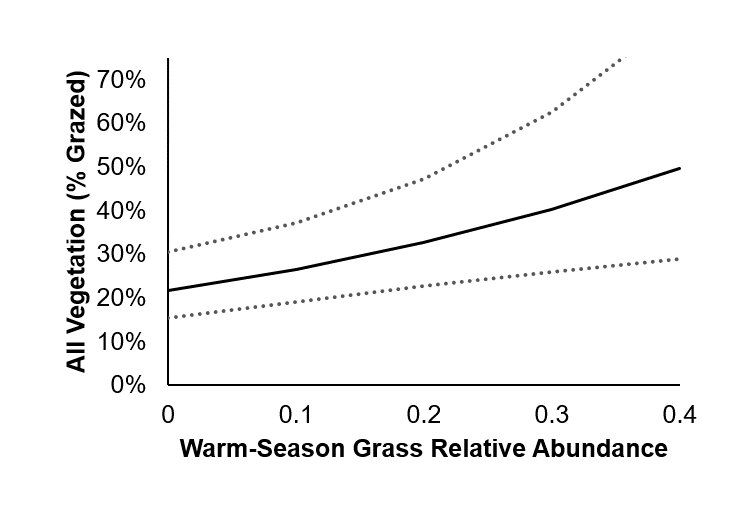

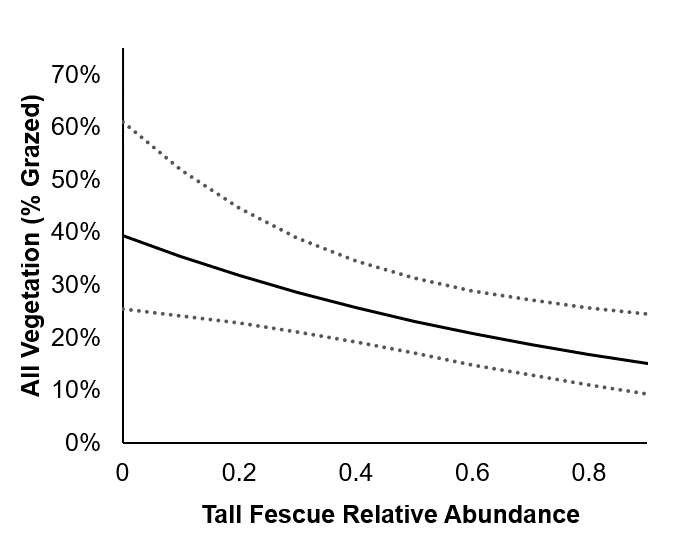

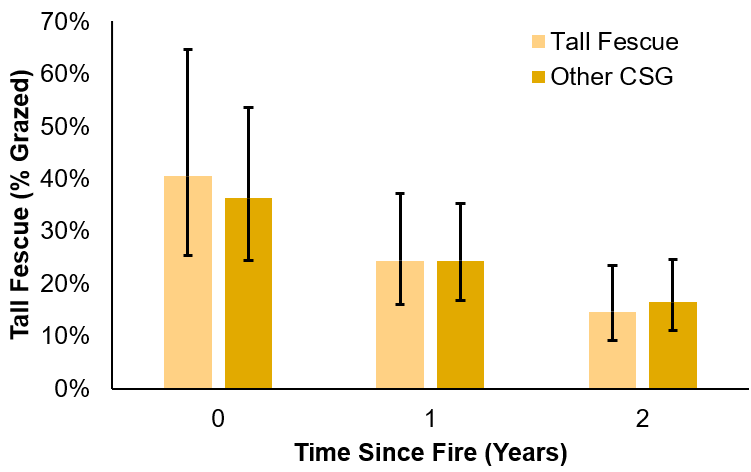

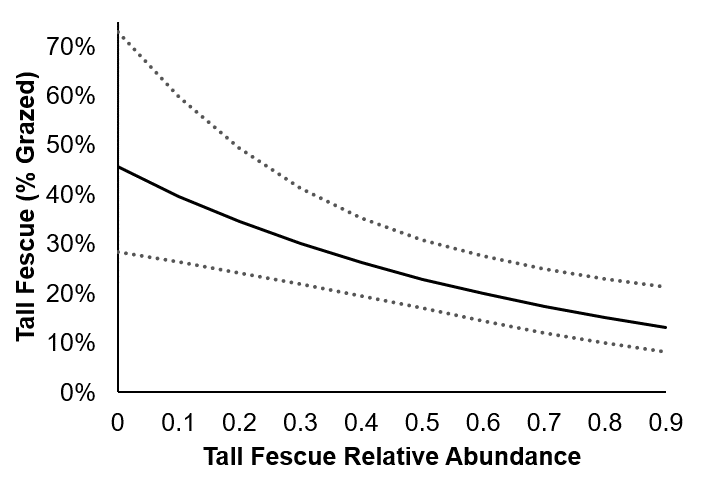

First, based on AICc rankings, total grazing pressure within sampling plots was influenced by warm-season grasses and tall fescue. As warm-season grasses increased from 0 to 0.4 in relative frequency, there is an increase in total percent grazed, from ~20% to ~45%, albeit with wide confidence intervals (Fig. 1). Conversely, as tall fescue increased in relative abundance from 0 to 0.9, the percent of vegetation grazed decreases from ~40% to ~17% (Fig. 2). Time-since-fire and the relative abundance of tall fescue were the top-ranked candidate models explaining grazing pressure on tall fescue. As time since fire increased from 0 years to 2 years, the percent of tall fescue grazed decreased from ~40% to 15%, with clear separation between year 0 and 2, supported by non-overlapping 85% confidence intervals (Fig. 3). Additionally, as the relative frequency of tall fescue increased from 0 to 0.9, the percent of tall fescue grazed decreased from ~45% to ~18% (Fig. 4).

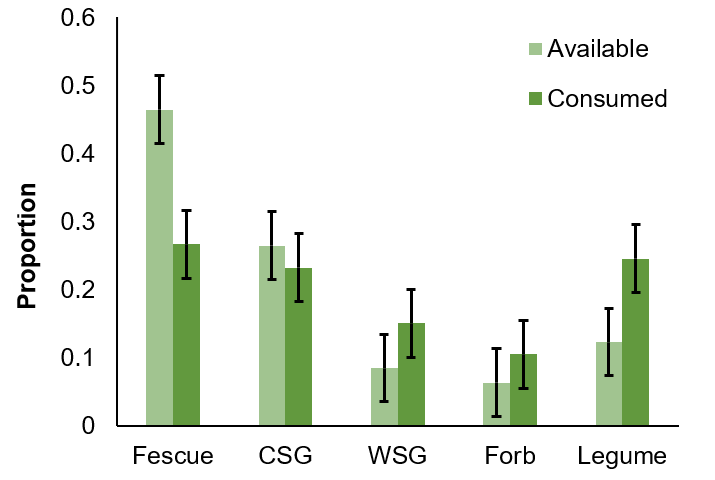

Additionally, cattle used some forages disproportionately to their relative abundance (F(9, 27)=9.71, p<0.001; Fig. 5). Although tall fescue was the most abundant forage in the pastures, comprising 46.4% of categorized plants (85% confidence interval: 41.5-51.4%), it constituted only 26% (21.7-31.6%) of all grazed plants. In contrast, even though legumes accounted for only 12.3% (7.3-17.3%) of plants, they constituted 24.6% (19.6-29.5%) of all plants grazed—similar to use of both tall fescue and non-fescue cool-season grasses. Non-fescue cool-season grasses, warm-season grasses, and forbs were grazed in proportion with their abundances (i.e., confidence intervals around relative abundance and use estimates overlapped).

Our results show that although cattle graze tall fescue, particularly following burns, they limit their use of this grass. Given that tall fescue is underused, creates health risks for cattle, and degrades wildlife habitat quality, it may be advisable to reduce tall fescue in pastures.

These results are now published in the following article:

Maresh Nelson, SB, JJ Coon, WH Schacht, and JR Miller. 2019. Cattle select against the invasive grass tall fescue in heterogeneous pastures managed with prescribed fire. Grass and Forage Science. [co-first authors] Link: MareshNelson_etal_2019

Ecological Objective 1: Improved understanding of the impact of tall fescue abundance on ecological communities

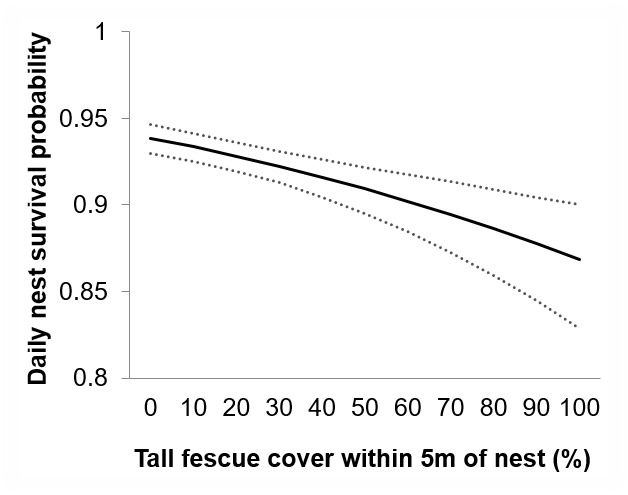

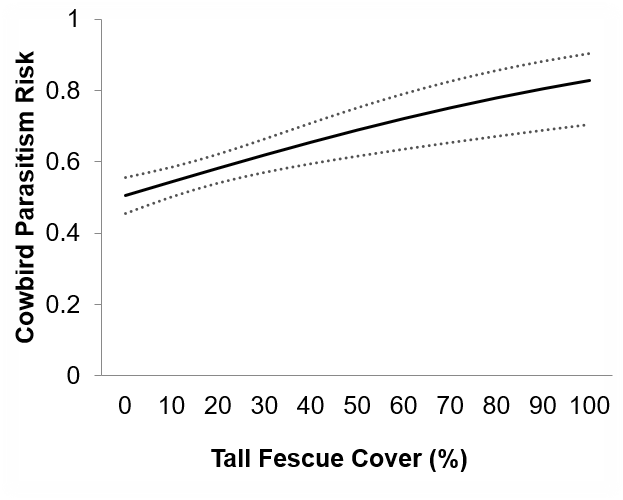

To explore the impact of tall fescue on ecological communities, we estimated the daily nest survival probabilities using the logistic exposure method. We compared multiple models using an information-theoretic approach to examine the impact of both landscape and local habitat variables on nest survival. This analysis includes 477 dickcissel nests found between 2013-2016. We found that nest survival decreased with increasing tall fescue cover near dickcissel nests (Fig. 6), and that parasitism by brown-headed cowbirds was higher when there was more tall fescue (Fig. 7). We also incidentally observed a dickcissel committing parental infanticide on camera while monitoring nests, the first such observations in dickcissels and one of very few such observations for grassland birds.

These results are now published in the following articles:

Maresh Nelson, SB, JJ Coon, CJ Duchardt, JR Miller, DB Debinski, and WH Schacht. 2018. Contrasting impacts of invasive plants and human-altered land cover on nest survival and parasitism of a grassland bird. Landscape Ecology. doi:10.1007/s10980-018-0703-3. Link: MareshNelson_etal_2018

Coon, JJ, SB Nelson, IA Bradley, AC West, and JR Miller. 2018. Parental infanticide in Dickcissels (Spiza americana): video evidence and a review of potential mechanisms. Wilson Journal of Ornithology, 130(1). Link: Coon_etal_2018

Analysis of avian (2007-2018) and arthropod (2015-2018) monitoring data is ongoing. From 2007-2018, we sighted 89 species of birds, including 23 species of obligate or facultative grassland birds. This dataset includes sightings of 32,931 individual birds. In addition, from 2015-2018 we collected 155,453 arthropods and measured 45,071 individuals from arthropod orders commonly eaten by grassland birds (Orthoptera, Lepidoptera, Coleoptera, and Araneae).

These data are being analyzed and prepared for publication in several peer-reviewed articles.

Ecological Objective 2: Improved understanding of the impact of tall fescue removal on ecological communities

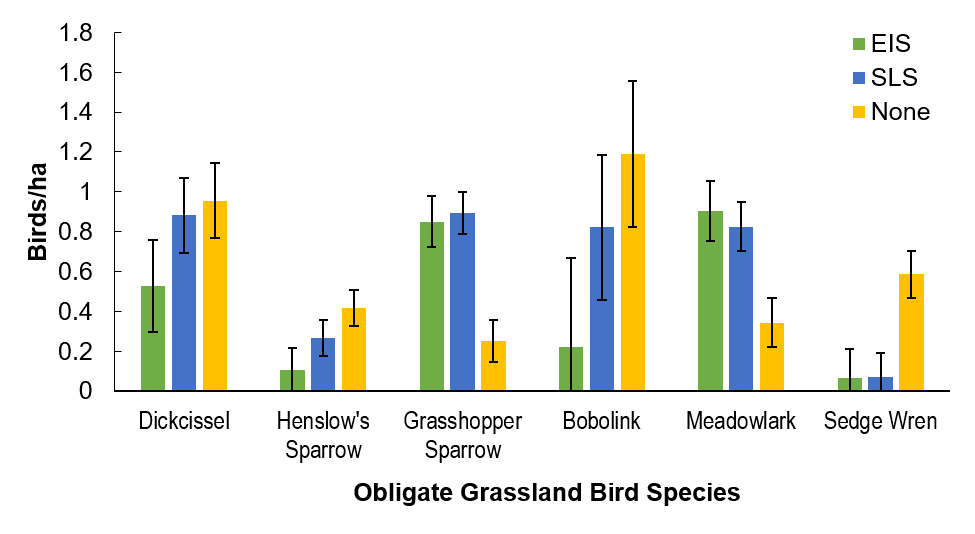

The goal of these analyses is to determine the effects herbicide application and grazing method on (1) individual bird species of concern and (2) avian richness. To calculate species densities, we found the maximum number of individuals ever observed on a single visit, for each of the three patches per pasture. We then divided these numbers by the area sampled (transect length x transect width, converted to birds/ha). Group sizes greater than 3 were excluded to control for effects of flocking. In these analyses, we distinguished between grassland obligate and grassland facultative species. Obligate grassland species are species exclusively adapted to grassland habitats and rarely if ever use other habitat types, whereas facultative species use grasslands regularly but do not depend on them entirely. Richness is the total number of species spotted on a pasture or patch over the course of the season, calculated for both obligate species alone and obligate and facultative species combined.

Next, we used general linear mixed models to compare patches with herbicide application (spray), herbicide application and native seeding (spray & seed), and patches without herbicide application (control). In these analyses, we compared single-species density of obligate and facultative species and overall grassland bird richness to these patch treatments for the eight pastures with controlled herbicide application. Pasture was included as a random effect to control for the non-independence of observations taken from the same pasture. Second, we constructed general linear models to examine the effect of to harvest method (i.e., early intensive stocking, continuous stocking, or no grazing) on single-species densities and richness of grassland birds. In 2017, we began looking at multiple years of these data at once to see if there were any lag effects associated with treatment application.

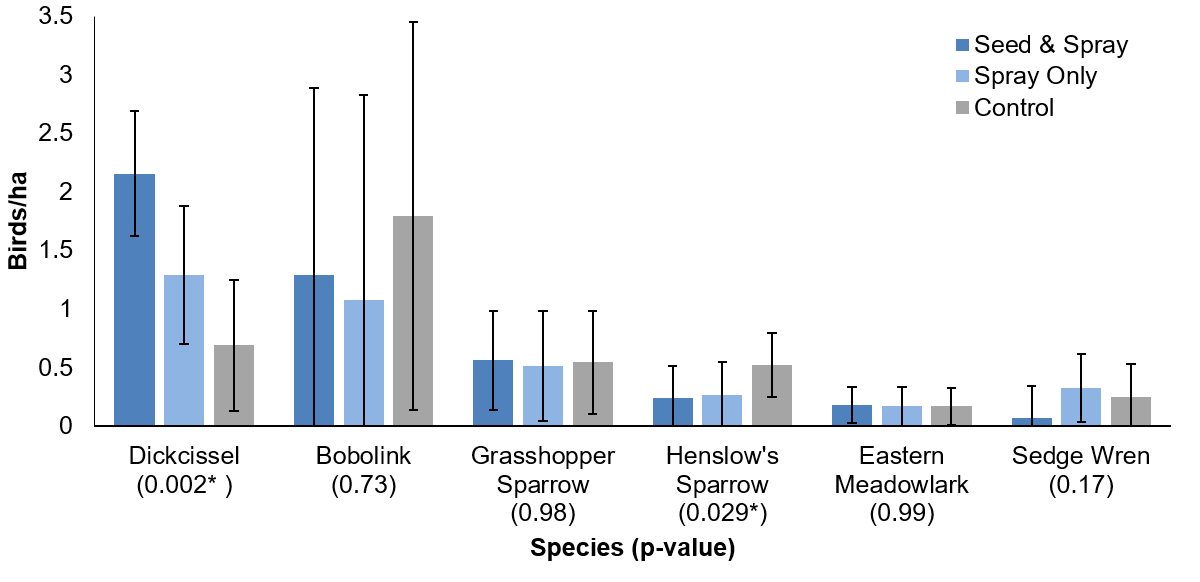

Several obligate grassland birds responded to herbicide application, although these changes differed by species (Fig. 8). Dickcissels were most abundant on spray & seed patches, following by sprayed and then control patches (p=0.002). Conversely, Henslow’s sparrows were most abundant on control patches, with no distinction between spray & spray and spray-only patches (p=0.029). No statistically significant effects were detected for bobolinks, grasshopper sparrows, Henslow’s sparrows, eastern meadowlarks, or sedge wrens (p>0.1). We did not detect any response to these treatments by facultative species (Fig. 2, p>0.1) or total grassland bird richness (p>0.1).

We were able to detect several species-specific effects of harvest method on avian density for obligate species (Fig. 9) and facultative species. For obligate species, dickcissels were most abundant on pastures with no grazing and least abundant on pastures with intensive early stocking, with continuous stocking fall between these treatments (p=0.029). This pattern is also present for bobolinks (p=0.13) and Henslow’s sparrows (0.12), although these results are not statistically significant at α=0.1. Sedge wrens were also most abundant on ungrazed pastures, and were mostly absent from grazed pastures of either treatment (p<0.001). In contrast, grasshopper sparrows were least abundant on pastures without grazing, and had essentially equivalent densities on the two grazing treatments (p=0.078). Eastern meadowlarks were slightly more abundant on both grazing treatments when compared to ungrazed pastures, but effect sizes are small and not statistically significant (p=0.12).

For facultative species, red-winged blackbirds were most abundant on pastures without grazing, with equivalent densities on the two grazing treatments (p=0.0025), with similar trends also seen for common yellowthroats (p=0.005). No significant trends were observed for eastern kingbirds, brown-headed cowbirds, or field sparrows. There were no detectable effects of harvest method on species richness (p>0.1).

Beginning in 2017, we also examined time-since-treatment over the course of the herbicide experiment (2014=baseline, experiment=2015, 2016, and 2017). We found that grasshopper sparrows decreased in abundance one-year post-treatment compared to both baseline abundances and control patches (p=0.095). However, grasshopper sparrows have since increased in the three years since herbicide and seeding treatment was applied. Conversely, dickcissels increased significantly one-year after treatment and have stabilized at relatively higher abundances three-years after treatment (p<0.0001). It is notable that 2015 was the year we saw these increases since that year was generally low in dickcissel abundances in the region.

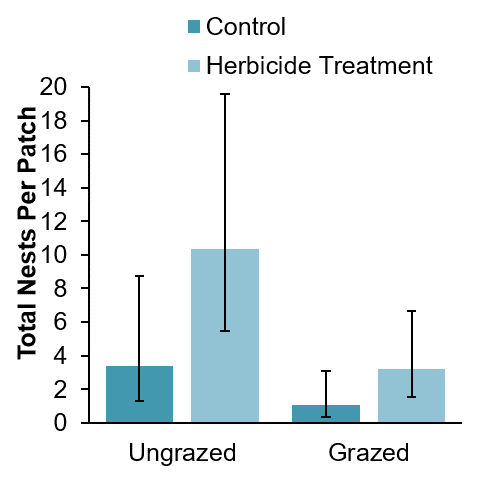

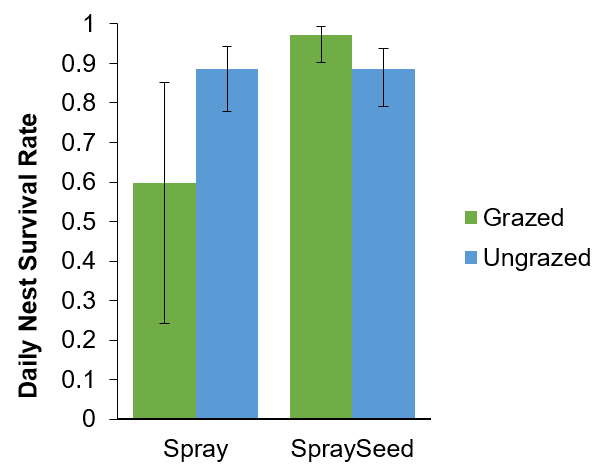

We have also completed a second set of analyses examining the impact of experimental fescue removal using herbicide on nesting dickcissels, listed as a species of greatest conservation need. In 2016, we found that there were more dickcissel nests found on patches where fescue had been removed (p=0.08) (Fig. 10). This relationship was found on both grazed and ungrazed pastures, although less nests overall were found on grazed sites (p=0.04). In addition, more dickcissel fledglings were produced from spray sites, with an average of 1 dickcissel fledgling produced from a control patch and 4 fledglings from either the spray or spray-and-seeded patch (p=0.08; number of nests held at average 5 nests/patch). Again, using the logistic exposure method to explore daily survival rate, we found that daily survival was highest on spray and seeded patches (p=0.01), and that the few nests placed on grazed patches without native seeding did not survive very long (Fig. 11).

These data are being analyzed and prepared for publication in several peer-reviewed articles and will also be published in J. Coon’s dissertation, which will be deposited to the Ideals @Illinois database (www.ideals.illinois.edu).

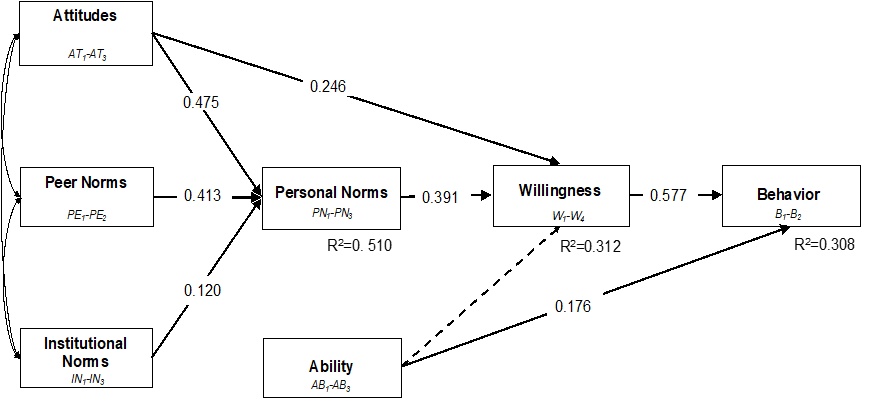

Social Objective 1: Understanding of potential barriers to and opportunities for invasive grass removal

When exploring landowner willingness to manage invasive grasses like tall fescue, we analyzed ours survey data by integrating two theories, the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and the Norm Activation Model (NAM), to evaluate how attitudes, norms, perceived ability, and willingness influenced management of non-native plants using methods such as herbicide or physical removal. Using structural equation modeling (SEM) techniques, we tested hypotheses derived from a merged TPB-NAM model. Using these methods, we found that both internal factors (Attitudes, Personal Norms) and external factors (Social Norms, Perceived Ability) influenced landowners’ decisions (Fig. 12). Landowners who viewed management positively (Attitudes) and who felt social pressure (Social and Institutional Norms) also felt a stronger obligation (Personal Norms) to manage non-native grasses. These feelings of obligation and positive views toward management then increased Willingness to manage. Landowners who had access to resources (Perceived Ability) managed non-native grasses more frequently (Reported Behavior).

These results indicate that a lack of resources (e.g. equipment or skills) could be a barrier for people wishing to manage non-native grasses. Thus, providing access to equipment, information on best practices, or training through field days where landowners can practice or observe management may contribute to increased Perceived Ability to take on management. However, simply providing resources or information is unlikely to change behavior, and our results indicate that one such motivational element could be Social Norms. Creating cooperative networks of landowners working to reduce non-native grasses, along the same lines as cooperative burning associations, may simultaneously provide access to skills and resources and leverage Social Norms.

Personal Norms were another strong driver of Willingness to manage non-native grasses in our study. As such, another motivational tactic for non-native grass control initiatives could be to use messaging to activate landowners’ sense of moral responsibility. Stewardship, which considers ecological function a ‘public good’, connects conservation on individual private lands to well-being at the landscape scale. Given the potential of Personal Norms and stewardship values to influence behaviors related to invasive species, managers and researchers could use messaging that reinforces landowners’ existing sense of moral responsibility, reminding them that removing non-native grasses can help wildlife, cattle production, and scenic value in their communities.

These results are being prepared for publication in several peer-reviewed articles and will also be published in J. Coon’s dissertation, which will be deposited to the Ideals @Illinois database (www.ideals.illinois.edu).

Coon, JJ, CJ van Riper, LW Morton, and JR Miller. In Prep. Exploring non-response bias using a follow-up survey on wildlife attitudes in the rural Midwest.

Coon, JJ, CJ van Riper, LW Morton, and JR Miller. In Prep. Landowner willingness to manage non-native grasses in the eastern Great Plains: the influence of attitudes, norms, and perceived abilities on behavior.

Social Objective 2: Longitudinal analysis showing change in attitudes (2007-2017)

This report summarizes key differences between the 2017 survey and a similar survey conducted in 2007. Although landowner demographics were similar between 2007 and 2017, several changes occurred over the ten-year period. Respondents owning land in the GRG for greater than 25 years increased from 59% in 2007 to 67% in 2017. In addition, respondents owning land for 10 years or less dropped from 20% in 2007 to 7% in 2017. This suggests that there has been very little ownership turnover in ten years. GRG landowners in 2017 had on average 315 acres of open pasture and grassland, 147 acres of corn/soybean, 47 acres of woodland including 3 acres of redcedar, and about 5 acres of small grains. Eighty percent reported having one to four ponds on their property. About half of the respondents in both 2007 and 2017 were row-crop farmers. Respondents using their land for a weekend retreat or vacation home more than doubled from 2007 (5%) to 2017 (11%). Although most GRG landowners value income from agriculture, there was a drop in the percentage of landowners rating it as very or extremely important, from 81% in 2007 to 70% in 2017.

Cattle ranching is a major land use in the GRG. Ninety-five percent of cattle ranchers were moderately to extremely satisfied with their growing season forage in 2017. Less than 25% of respondents would adopt reduce beef production per acre regardless if it would result in an increase in gamebirds, reduce tall fescue, protect wildlife, restore grassland, or increase native plants. A few more respondents said they would be very/extremely likely to try this trade-off if it reduced soil erosion (35%) or controlled invasive plants (32%). Twenty-eight percent thought non-native tall fescue must be removed from their land. Cattle producers specifically are very concerned about the effects of having too much fescue in their pastures. If this leads to a willingness to manage and reduce tall fescue in grazing pastures, there is strong potential for both wildlife habitat restoration and benefits to cattle production systems.

Herbicides are a management strategy for removing non-native grasses and managing woody encroachment in fields. While the majority of respondents were concerned about a number of risks to using herbicides, they were most concerned about soil erosion after use (72% moderately/extremely concerned) and herbicide resistance (69%). A high proportion of respondents to the 2017 survey believed that native warm season grasses are good for wildlife and grazing compared to fields of the invasive grass tall fescue.

Game species, especially bobwhite quail, remain highly important to residents, but most non-game wildlife has less importance to landowners in 2017 compared to 2007. The exception to this is bees, which respondents see as very important to have on their lands. It is likely that landowner awareness and concern have been raised by the well-publicized threats to bees in the popular press over the last several years.

There has been a net gain in grassland acres in the region, but large acreages continued to shift back and forth between crop and grassland in the last five years. This may reflect the downturn in the crop and cattle prices that has occurred in recent years.

While positive attitudes toward conservation seem to have eroded in some areas (with exceptions) over the ten-year period, more landowners are taking part in activities that are good for conservation and restoration. For example, fewer landowners believe that grassland restoration on their land is important in 2017 vs. 2007. However, more landowners are using prescribed fire and physically removing woody plants, activities that promote grassland restoration. There are clear advantages to focusing on how management activities related to restoration have the potential to benefit production goals as well as wildlife habitat.

These results are now published in the following technical report:

Coon, JJ, LW Morton, & JR Miller. 2018. A survey of landowners in the Grand River Grasslands: Managing wildlife, cattle, and non-native plants. Report 04-18, University of Illinois Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Sciences, Urbana, IL. <Deposited at Ideals @Illinois>

Link: Coon_etal_2017

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation summary:

Social Objective 3: Enhanced knowledge in the community about invasive species

Outreach Objective 1: Increased interest in sustainable agriculture in a grassland context

Outreach Objective 2: Increased literacy in areas of grassland ecology

We sought to achieve these objectives through several means. To enhance knowledge in the community about invasive species, grassland ecology, and sustainable agriculture (Social Objective 2, Outreach Objective 1 & 2), we began an internship program that focused on teaching wildlife sampling techniques. In 2016 and 2017, we worked with three interns. They worked 10-30 hrs/wk and had the option of receiving course credit through their universities. We initiated an “Intern for a Day” program, where high school or undergraduate students could come and participate in our research for a day or more. In 2016, we hosted one high school student over four days. In 2017, we engaged two undergraduate students affiliated with The Nature Conservancy in this program and worked with them over two days. Several of our interns have received employment or further internships in the wildlife field, including at the Des Moines Zoo, NOAA, and the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe reservation.

We also made connections with high school teachers in the area, and have developed lesson plans centering on sustainable agriculture and biodiversity in collaboration with educators. We have distributed these lesson plans to several teachers local to the Grand River Grasslands.

Link: Biological diversity in working grasslands, lesson plans

In addition, over the three years of this project, 10 undergraduate students have completed independent projects or served as field or lab technicians under the mentorship of project participants. These trainees have applied for their own funding, presented at conferences, some have co-authored manuscripts and/or have gone on to attend graduate school themselves.

Third, we have presented our work at both academic conferences and agency/landowner meetings to disseminate our findings and increase knowledge of invasive species in the region (listed below). To highlight a few notable presentations, in summer 2017 we organized a meeting in the Grand River Grasslands that included past collaborators (~10 people), land managers (~15 people) from multiple organizations, and local landowners (~10 people) for a full day of presentations and discussion. In addition, we presented results from this project to a mixed audience of producers, agency personnel, and researchers on several other occasions, including at the Society for Range Management annual meeting in 2019.

Presentations (Complete List)

Presentations by Project Participants (*indicates undergraduate trainees)

Coon, JJ, CJ van Riper, LW Morton, and JR Miller. June 2019 (Accepted). Exploring landowner willingness to manage non-native plants in the eastern Great Plains: the influence of attitudes, norms, and perceived abilities on behavior. Presentation at the International Symposium on Society and Resource Management (ISSRM) in Oshkosh, WI.

Coon, JJ, SB Nelson, NJ Lyon, EJ Raynor, DM Debinski, WH Schacht, and JR Miller. April 2019 (Accepted). Grassland bird, arthropod, and vegetation response to invasive grass management: Results of a landscape-scale experiment. Presentation at the US Section of the International Association for Landscape Ecology (US-IALE) Annual Meeting in Fort Collins, CO.

Maresh Nelson, SB, JJ Coon, JR Miller, DM Debinski, WH Schacht. April 2019 (Accepted). Can grassland birds rely on vegetation cues to select high-quality habitats in human-dominated landscapes? Annual Meeting of US-IALE in Fort Collins, CO.

Maresh Nelson, SB, JJ Coon, JR Miller, WH Schacht, DM Debinski. Feb. 2019. Tall fescue: an invasive grass impacts songbirds and cattle in a working landscape. Presentation at the Ohio Invasive Plant Research Conference in Columbus, OH. Link to presentation slides.

Raynor, EJ, JJ Coon, NJ Lyon, H Hillhouse, WH Schacht, DM Debinski, and JR Miller. Feb. 2019. Managing invasive cool-season grasses with grazing, fire, and herbicides in the eastern Tallgrass Prairie. Presentation at the Society for Range Management Meeting in Minneapolis, MN.

Coon, JJ, EJ Raynor, LW Morton, CJ van Riper, and JR Miller. Feb. 2019. Grazing, Fire, and Non-native grasses: Possibilities for conserving biodiversity on privately-owned grasslands. Presentation at Graduates in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Symposium in Urbana, IL. (Best Overall Talk, Graduate Student Judges; Best Post-Prelim Talk, Faculty Judges)

Coon, JJ, EJ Raynor, TM Swartz, LW Morton, CJ van Riper, WH Schacht, JR Miller. Feb. 2019. Decision-making on privately-owned grasslands: Stocking rate, non-native grasses, and changing perceptions toward conservation. Presentation at the Society for Range Management Meeting in Minneapolis, MN. Link to presentation slides.

Coon, JJ, CJ van Riper, LW Morton, and JR Miller. Sep. 2018. Exploring landowner willingness to manage non-native plants in a working landscape: the influence of social groups and personal obligation. Paper presented at the Nature-Society Workshop in Madison, WI.

Coon, JJ, SB Nelson, LW Morton, and JR Miller. Apr. 2018. Landowners, non-native plants, and grassland birds: Exploring possibilities for management on privately-owned pastures that serve as wildlife habitat. Presentation at the US-IALE Annual Meeting in Chicago, IL.

Coon, JJ, JR Miller. Apr. 2017. Habitat and livelihoods: the effects of a non-native plant on grassland wildlife in a complex human-dominated environment. Poster at the US-IALE Annual Meeting in Baltimore, MD.

Nelson, SB, JJ Coon, IA Bradley, and JR Miller. March 2017. Defining the consequences of anthropogenic habitat change: Impacts of plant invasions and land conversion on grassland bird nest ecology. Presentation at the Midwest Ecology and Evolution Conference in Urbana, IL.

Coon, JJ, and JR Miller. Feb. 2017. Grassland bird response to removing invasive tall fescue (Schedonorus phoenix). Presentation at the Graduates in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Symposium in Urbana, IL.

Coon, JJ and JR Miller. Feb. 2016. Tall fescue in a social-agricultural system. Poster at the Graduates in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Symposium in Urbana, IL. (Best Poster Award, JJ Coon)

Presentations at Agency/Collaborator/Landowner Meetings

Coon, JJ, LW Morton, and JR. Miller. May 2018. Landowner Perceptions of Management and Conservation in the Grand River Grasslands: A Longitudinal Comparison (2007, 2017). Presentation at the Leopold Center Grand River Grasslands Report-Out Meeting in Mt Ayr, IA.

Coon, JJ, LW Morton, and JR. Miller. May 2018. Landowner Perceptions of Management and Conservation in the Grand River Grasslands: A Longitudinal Comparison (2007, 2017). Presentation at the 2018 Grand River Grasslands Future Directions meeting in Mt Ayr, IA.

Duchardt, CJ, JJ Coon, and JR Miller. May 2017. Grassland bird response to fire, grazing, and herbicide. Presentation at the Grand River Grasslands Symposium: Ten Years of Research - Key Findings and Future Directions in Lamoni, IA.

Coon, JJ, LW Morton, C.J. van Riper, and JR Miller. May 2017. Landowner attitudes toward non-native plants, native wildlife, and grassland management. Presentation at the Grand River Grasslands Symposium: Ten Years of Research - Key Findings and Future Directions in Lamoni, IA.

Nelson, SB, TJ Hovick, TP Lyons, JJ Coon, JR Miller. June 2017. Effects of invasive plants, fire, and grazing on grassland bird nesting ecology. Presentation at the Grand River Grasslands Symposium: Ten Years of Research – Key Findings and Future Directions in Lamoni, IA.

Presentations Led by Undergraduate Trainees (*)

*Bradley, IA, JJ Coon, SB Nelson, and JR Miller. Apr. 2018. Caught on camera: Provisioning behavior of a grassland songbird species of conservation concern. Poster at the Graduates in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Symposium in Urbana, IL. (Best Poster Award, IA Bradley)

*Daughtridge, RC, JJ Coon, *IA Bradley, and JR Miller. Apr 2018. Arthropod Response to a Landscape-Scale Herbicide Treatment: An Exploration of Grassland Birds’ Prey Base. Poster at the Undergraduate Research Symposium in Urbana, IL.

*Mattes, JR, TM Swartz, JJ Coon, and JR Miller. Apr. 2018. Assessing the Influence of Landowner Attitudes on the Availability and Quality of Amphibian Habitat in Human-Constructed Ponds. Poster at the Undergraduate Research Symposium in Urbana, IL.

*Repiscak, M, JJ Coon, JF Capozzelli, LR Lynch, and JR Miller. Apr. 2018. Evaluating habitat quality for shrubland birds, arthropods, and bee communities in human-dominated landscapes. Poster at the Undergraduate Researchers Initiative Symposium in Urbana, IL

*Wagner, M. *IA Bradley, JJ Coon, SB Nelson, and JR Miller. Apr. 2018. Caught on Camera: Documenting Nestling Diet of a Grassland Bird. Poster at the Undergraduate Researchers Initiative Symposium in Urbana, IL.

*Bradley, IA, JJ Coon, SB Nelson, and JR Miller. Apr. 2017. Caught on camera: Provisioning behavior of a grassland songbird species of conservation concern. Poster at the Undergraduate Research Symposium in Urbana, IL.

*Dong, S, *C Wessman, JJ Coon, and JR Miller. Apr. 2017. Conservation in working landscapes: controlling invasive species on private land. Poster at the Undergraduate Research Symposium in Urbana, IL.

*Johnson, J, JJ Coon, TM Swartz, JF Capozzelli, and JR Miller. Apr. 2017. Conservation in human-dominated grasslands of the Midwest: ponds, cattle grazing, and shrub encroachment. Poster at the Undergraduate Researchers Initiative Symposium in Urbana, IL.

*Wendling, A, JJ Coon, TM Swartz, JF Capozzelli, and JR Miller. Apr. 2016. Effects of land use on grassland biodiversity: birds, arthropods, and amphibians. Poster at the Undergraduate Researchers Initiative Symposium in Urbana, IL.

*Rola, KE, JJ Coon, and JR Miller. Mar. 2016. Effects of arthropod abundance within dickcissel (Spiza americana) territories on nestling body condition. Poster at the Midwest Ecology and Evolution Conference (MEEC) at Miami University in Oxford, OH.

Publications

In addition to sharing our research through presentations and mentoring, we are also working to publish our research. Several articles from this project have been published or are in review or in prep (listed below). J. Coon’s and S. B. Maresh Nelson’s dissertations will include data produced with the support of this grant, and both will be deposited to the Ideals @Illinois database (<www.ideals.illinois.edu>). We have also applied for and received several other small grants that have built on this project (listed below).

In Prep

Coon, JJ, SB Maresh Nelson, WH Schacht, DM Debinski, and JR Miller. In Prep. Grassland birds and their arthropod prey: community responses to invasive plant control and long-term management.

Coon, JJ, SB Maresh Nelson, IA Bradley, K Rola, and JR Miller. In Prep. Short-term impacts of experimental herbicide and native seeding on breeding ecology of a grassland bird.

Coon, JJ, CJ van Riper, LW Morton, and JR Miller. Landowner willingness to manage non-native grasses in the eastern Great Plains: the influence of attitudes, norms and perceived abilities on behavior.

Coon, JJ, NJ Lyon, EJ Raynor, DM Debinski, JR Miller, and WH Schacht. Using herbicide and seeding to restore grasslands dominated by invasive, cool-season grasses.

Coon, JJ, CJ van Riper, LW Morton, and JR Miller. Exploring non-response bias using a follow-up survey on wildlife attitudes in the rural Midwest.

In Review

Raynor, EJ, JJ Coon, TM Swartz, LW Morton, WH Schacht, and JR Miller. In Review. A social-ecological assessment of cattle producer views toward conservation, an invasive grass, and stocking rate. Submitted to Rangeland Ecology and Management.

Published

Coon, JJ, SB Nelson, IA Bradley, AC West, and JR Miller. 2018. Parental infanticide in Dickcissels (Spiza americana): video evidence and a review of potential mechanisms. Wilson Journal of Ornithology, 130(1). Link to PDF.

Coon, JJ, LW Morton, & JR Miller. 2018. A survey of landowners in the Grand River Grasslands: Managing wildlife, cattle, and non-native plants. Report 04-18, University of Illinois Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Sciences, Urbana, IL. <http://hdl.handle.net/2142/99941> Link to PDF.

Maresh Nelson, SB, JJ Coon, WH Schacht, and JR Miller. 2019. Cattle select against the invasive grass tall fescue in heterogenous pastures managed with prescribed fire. Grass and Forage Science. [co-first authors] Link to PDF.

Maresh Nelson, SB, JJ Coon, CJ Duchardt, JR Miller, DB Debinski, and WH Schacht. 2018. Contrasting impacts of invasive plants and human-altered land cover on nest survival and parasitism of a grassland bird. Landscape Ecology. doi:10.1007/s10980-018-0703-3. Link to PDF.

Project Outcomes

We found in our social research that many farmers and ranchers are concerned that tall fescue could adversely affect their livestock and are open to reducing its abundance on their lands. Our agricultural results suggest that although cattle certainly do graze tall fescue—even when alternative forages are available—its quantity could be substantially reduced in pastures where it is highly abundant without compromising forage quality. This is because tall fescue constituted a significantly smaller proportion of all vegetation grazed by cattle than expected given its prevalence, and that cattle used areas with low fescue abundance more heavily than areas with high fescue abundance. Ecologically, we have found that tall fescue can harm grassland birds. Conversely, controlling tall fescue using fire, grazing, and herbicide has complex impacts on grassland birds, with some sensitive species declining one year after herbicide application but returning in later years. Overall, reducing tall fescue abundance on grazing pastures may provide agricultural, social, and ecological benefits - potentially a 'win-win' opportunity. However, if land managers do not wish to remove it, our finding that cattle increase their use of tall fescue (and other cool-season grasses) following management with prescribed fire. Additionally, our social results suggest that landowners may be most effectively engaged in management programs aimed at reducing tall fescue by activating feelings of personal responsibility and stewardship. Our agricultural, social, and ecological findings will be useful when managing invasions by exotic plants that have agricultural value, and will help support development of sustainable agriculture practices aimed at reducing the abundance of these plants.

Over the course of this SARE graduate student grant, we have surveyed 149 landowners about their views toward tall fescue, interacted with dozens of landowners and agency personnel through conferences, meetings, and phone calls, and have built new collaborations with researchers across the U.S. We received 5 additional small grants to build on this work, and are currently seeking additional funding to investigate the results produced further.

Throughout this project, knowledge has been gained by the producers, agency personnel, trainees, and researchers through discussions, dissemination of results, and relationship-building. When sharing our results with producers, we have noticed that our tri-pronged approach (agricultural, ecological, and social methods) generates enthusiasm and thoughtfulness about the role of invasive grasses on productive grasslands. In addition, we have worked with numerous undergraduate and high school trainees who now are attending graduate school or have joined the workforce. These trainees have themselves presented at conferences and built connections of their own. Over the course of this project, we have learned that a key component of sustainable agriculture is the co-production of knowledge through the relationships we have established across a diverse set of stakeholders, which is a lesson that we will build upon in our future careers.

Additional Grants

Coon, JJ, JF Capozzelli. 2017. Grassland birds, an invasive grass, and arthropods: exploring relationships using a long-term avian dataset. Iowa Ornithologists’ Union Small Grant, $1014.

Coon, JJ, and JF Capozzelli. 2016. Biodiversity in working landscapes: Help us conserve declining grassland birds in restored Midwestern grasslands. Experiment.com Crowdfunding Grant, Ornithology Challenge Winner, $3921. <experiment.com/grasslandbirds>

Coon, JJ, and JR Miller. 2016. Expanding the sample size for a grassland management landowner survey. Illinois Sustainable Agriculture, Research, and Education Mini-Grant, $1500.

Coon, JJ. 2016. Grassland birds, an invasive grass, and arthropods: a potential trophic cascade in an actively managed landscape. Wilson Ornithological Society’s Louis Agassiz Fuertes Grant, $2500.

Nelson, SB, and JJ Coon. 2016. Exploring the impacts of an invasive grass on grassland bird habitat selection, behavior, and fitness. Garden Club of America Frances M. Peacock Scholarship for Native Bird Habitat, $4500.

Information Products

- Graduate Student Grant Update to NCR-SARE Staff: Agricultural, ecological, and social responses to an invasive grass and its removal in working Midwestern grasslands

- Lesson Plans on Biological Diversity in Working Grasslands

- An invasive grass impacts songbirds and cattle in a working landscape

- Grazing, prescribed fire, and non-native grasses: Possibilities for conserving biodiversity on privately-owned grasslands

- Cattle select against the invasive grass tall fescue in heterogeneous pastures managed with prescribed fire

- Contrasting impacts of invasive plants and human-altered landscape context on nest survival and brood parasitism of a grassland bird

- Survey of Landowners in the Grand River Grasslands: Managing wildlife, cattle, and non-native plants

- An observation of parental infanticide in Dickcissels (Spiza americana): video evidence and potential mechanisms