Final report for LNC19-422

Project Information

This project documented cultural and agronomic underpinnings of Three Sisters intercropping (3SI), with the overall objective of collaborating with Native gardeners to begin a 3SI research and education plot at Iowa State University’s Horticulture Research Station. Our central hypothesis was that working in collaboration with Native people to use their cultural knowledge of 3SI to design current gardening systems would result in improved yields and soil heath. Our rationale was that by working collaboratively with Native gardeners, our research would provide evidence for the socio-cultural, nutritional, and agroecological benefits of rejuvenating Native agriculture. Our specific objectives were to:

1) Assess the cultural, nutritional, and agricultural importance of 3SI among 5 Native American communities. To accomplish this objective, we used interviews, community surveys, and evaluations of geographic food availability to explore the impacts of revitalizing the practice.

2) Engage Native gardeners/farmers through citizen science. To accomplish this objective, we advanced our current collaborations with Native gardeners to collect soil and crop data from their own Three Sisters gardens.

3) Evaluate the effects of 3SI on crop yield and soil health. To accomplish this objective, we used citizen science data collected in Objective 2 and establish a collaborative long-term 3SI research and education plot at Iowa State University, designed with direct input from Native gardeners.

Learning outcomes included increased awareness of the cultural, nutritional and agroecological value of 3SI to Native communities. Native participants gained deeper knowledge of soil health and the skills to test their soil. Action outcomes included improved agroecological practices for soil health. Participants took soil tests and implemented new practices based on the results.

Learning outcomes included:

1) increased awareness of the practice of 3SI and its historical, cultural, and nutritional value to the community.

2) deepened knowledge of soil health, the connection to nutrition, and the acquisition of skills to test their soil.

Action outcomes included:

1) broadened and deepened community engagement with personal and community gardening (via learning outcome 1).

2) improved agroecological practices that promote soil health through learning outcome

3). Long term action outcomes of our collaborations included developing improved strategies for 3SI to increase the sustainability of Native communities and greater cooperation among ISU and Native communities and partners.

Reuniting the Three Sisters explored the cultural and agronomic underpinnings of the Native American practice of intercropping corn/maize (Zea mays), common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris), and squash (Cucurbita moschata)—colloquially called the Three Sisters. Because Native American communities in the Midwest have limited access to healthy, fresh foods, Native growers have established community gardens to incorporate culturally appropriate Indigenous growing practices, including the Three Sisters, to build community and improve health. Yet, support systems for these gardens remains inadequate. Thus, there is a critical need to determine the production barriers that Native gardeners experience and design research that demonstrates ways to improve soil/plant/human health. Without such knowledge, developing culturally appropriate agronomic strategies to help increase community gardening in Native communities will remain stymied. Our project sought to add to this knowledge.

Cooperators

Research

This project documented cultural and agronomic underpinnings of Three Sisters intercropping (3SI), with the overall objective of collaborating with Native gardeners to begin a 3SI research and education plot at Iowa State University’s Horticulture Research Station. Our central hypothesis was that working in collaboration with Native people to use their cultural knowledge of 3SI to design current gardening systems would result in improved yields and soil heath. Our rationale was that by working collaboratively with Native gardeners, our research would provide evidence for the socio-cultural, nutritional, and agroecological benefits of rejuvenating Native agriculture. Our specific objectives were to:

1) Assess the cultural, nutritional, and agricultural importance of 3SI among 5 Native American communities. To accomplish this objective, we used interviews, community surveys, and evaluations of geographic food availability to explore the impacts of revitalizing the practice.

2) Engage Native gardeners/farmers through citizen science. To accomplish this objective, we advanced our current collaborations with Native gardeners to collect soil and crop data from their own Three Sisters gardens.

3) Evaluate the effects of 3SI on crop yield and soil health. To accomplish this objective, we used citizen science data collected in Objective 2 and establish a collaborative long-term 3SI research and education plot at Iowa State University, designed with direct input from Native gardeners.

Learning outcomes included increased awareness of the cultural, nutritional and agroecological value of 3SI to Native communities. Native participants gained deeper knowledge of soil health and the skills to test their soil. Action outcomes included improved agroecological practices for soil health. Participants took soil tests and implemented new practices based on the results.

The team for this project, Reuniting the Three Sisters, built relationships with gardeners/farmers from the Omaha, Oneida, Ho-Chunk, and Meskwaki nations and Minneapolis’s Native community using two internal Iowa State University (ISU) grants, the Bridging the Divide grant and LAS Social Science research grant. They provided us with the funding to travel to communities to build relationships and collaboratively design our research plan. We created a research plan at a meeting of gardeners/farmers from each participating community in April 2018. We received solid commitments from twelve farmers/gardeners, including both farms and independent gardeners at Oneida, Jesskia Greendeer, an independent gardener at Ho-Chunk, and the Nebraska Indian College which serves the Omaha nation, the Santee nation, and the Sioux City urban community. The directors of Red Earth Gardens in Meskwaki have recently changed, so we worked with their garden team to attain their commitment. We met with Red Earth directors twice and have been in regular email contact. Ultimately, we never received a commitment from them, even though we continued to reach out. One of our grad students, who was from Meskwaki, worked with some of the growers there, but none decided to participate in the research component.

During preliminary interviews, Native farmers/gardeners described concerns about sustaining soil health, weed management, irrigation, and the connection between soil health and community nutrition. At our annual advisory board meeting of the research team and Native growers, we collaboratively decided to implement a long-term 3SI research experiment at ISU as well as satellite citizen science plots in each community.

The centralized ISU research and education/extension experiment and the satellite plots on Native community gardens complemented each other. We began citizen science soil testing in each community in the Spring of 2018 and traveled to each community in 2019 to take soil samples. We attempted to collect samples from growers during 2020 through the mail. We also developed the ‘main’ experiment at the ISU Horticulture Research Station--2020 was our first growing season. We collected the same data at each and held extension events at the ‘main’ experiment in 2020 because we were not allowed to travel. We continued to hold events at each community in 2021 and 2022.

Through ethnography, interviews, and listening sessions, Native gardeners/farmers collaborated to identify appropriate varieties to plant at all locations, the best planting techniques, and the experimental design. They also helped develop the soil and plant response data lists that were measured at the ‘main’ and ‘satellite’ 3SI sites. All sites were randomized, replicated complete block designs with four treatments– three treatments of each 3SI crop planted individually [sweet corn (Zea mays), common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris), and squash (Cucurbita moschata)], and a fourth treatment with all three planted together. In the 2022 growing season, the sisters were changed to Winnebago Spotted corn, Scarlet Runner beans, and Red Warren Turban squash. The seed varieties were chosen based on community interest and susceptibility to challenges from the previous years (ex., smut and bacterial pathogen Xanthomonas cucurbitae).

In 2020, three growers were able to grow these research plots, much less than our expected number because most growers were using all available space for food as a result of the pandemic. In 2020, our team designed a ‘do-it-yourself’ soil health kit for Native farmers to analyze the effect of 3SI on soil health. We also provided laboratory tests of plant available nutrients and selected soil health properties in 2020, 2021, and 2022. The data from ‘main’ and ‘satellite’ 3SI sites were collated, synthesized in short reports, and discussed with Native farmers/gardeners. Our team was in regular touch with each on-farm collaborator to assist in plot establishment and data collection. ISU Horticulture Research Station staff helped with the maintenance of the main experiment.

As stated before, we used ethnography, interviews, and surveys to demonstrate the sociocultural importance of 3SI for Native communities. The primary technique of ethnography requires participant observation. This methodology acquires data through careful observation while spending time in a community, getting to know its members, and learning about cultural practices by watching and participating when asked. The technique helps the researcher gain in-depth cultural knowledge because active engagement helps build trust between participants and researchers. Interviewing is also a central technique associated with ethnography. This project used the snowball sampling technique to recruit participants to interview and survey. A snowball sample involves approaching knowledgeable and prominent community members, introducing the research, and, once community members are engaged in the project, asking them to introduce the project to others who might be interested in participating. When the researcher brings new participants to the project, he or she asks them to suggest other potential participants. In this way, the researcher’s potential group of interviewees “snowballs.” We had contacts in each community who were in the position to introduce us to several potential participants who were knowledgeable about 3SI, and we were able to conduct interviews with these participants.

Our specific objectives were:

Objective One: Assess the cultural, nutritional, and agricultural importance of Three Sisters Intercropping (3SI) among 5 Native American communities.

Drs. Gish Hill and Winham led this objective, which considers the decision-making process involved in revitalizing Indigenous agricultural practices, including the use of cultural knowledge to determine varieties and growing practices, food preparation, and consumption of agricultural products, asking critical questions related to the sociocultural, agronomic, and nutritional reasons behind 3SI. We used ethnography, interviews, and surveys to demonstrate the sociocultural importance of 3SI for Native communities.

Our ethnographic research involved visits to each community each year, as well as email and phone conversations with participants to ask about their gardens, the cultural importance of the practice, the techniques they used, their concerns over soil health, and other barriers to successful production. We could not travel to sites in person during 2020 but conducted interviews over zoom and Webex. These conversations were recorded with permission, either on a digital audio recorder or as written notes by the PI, Dr. Gish Hill. Student research assistants and PIs also conducted informal interviews during 2019, 2021, and 2022 while visiting gardeners to introduce and demonstrate the use of the soil test. These visits were put on hold during 2020 due to the pandemic.

The ethnographic research resulted in hours of digital recordings of interviews and copious field notes. The interview recordings were transcribed and coded by hand. Hand coding classified, sorted, and arranged the data, looked for themes, examined relationships between the data, and identified trends. We have been returning transcriptions to interviewees for feedback and to potentially provide deeper insight into the initial interviews. We have also begun comparing the data we acquired with historical material to understand possible changes in the practice of 3SI over time. This analysis will provide information about the social and cultural understandings surrounding 3SI in the Native communities.

To evaluate the available food environment with a focus on the Three Sisters and other traditional foods, Dr. Winham and a trained undergraduate researcher assessed retail food stores, farmers’ markets, and food pantries on and within a 20-mile radius of each Native nation. We initially used the Nutrition Environment Measures Survey for Stores (NEMS-S) to guide the development of an ethnic-specific modification based on two of our partner Nations. Price comparisons for standard staples from the NEMS-S and traditional foods were compared across locations. We had previously developed a Latino ethnic store instrument for the Midwest and applied our experiences from that. Our analysis included relevant access details such as distance to stores from representative community clusters, food costs, and food quality, e.g., the freshness of produce. As we built rapport with community members, we directly explored qualitative views of food insecurity and access.

In our first two years, our assessments were “noninvasive” and focused on the built environment. We utilized publicly available statistics on food insecurity, food deserts, and epidemiological statistics for tribal member health. Our food environment findings on accessibility, availability, and affordability of healthy foods were reported to the community as the research evolved to invite input on our research plan. The nutrition environment measures generated descriptive statistics on the frequencies of food accessibility, availability, and affordability within reservation food outlets and those in a 20-mile radius of reservation boundaries. The original NEMS-S rating was compared with that of the Native American NEMS-S using paired t-tests to measure the difference in scores for each store. These findings quantified the presence or absence of food deserts, traditional foods, and pricing differentials for healthy foods by market source.

Objective Two: Engage Native gardeners/farmers through citizen science.

Dr. Nair led this objective. He organized on-farm visits and set up local focus group meetings and listening sessions to discuss the project’s progress. To accomplish this objective, we conducted multiple extension events and conversations with Native farmers to develop their own individual randomized-replicated 3SI experiments. These experiments tested the effect of monocropped maize, beans, and squash compared to when they are planted together as 3SI. Using funding from an internal ISU grant, we held one meeting in April 2018 with gardeners/farmers from each of these communities and discussed the experimental plots during this meeting. Continuing visits to each community and discussions strengthened these relationships and fostered trust between ISU researchers and the leaders and members of Native communities. On-farm visits to randomized-replicated 3SI experiments on grower/gardener plots allowed the team to effectively communicate with Native gardeners and local community leaders and disseminate information regarding crop rotation, soil fertility, integrated pest management strategies, and long-term soil quality and health. These listening sessions facilitated discussions and created opportunities for further understanding and development of 3SI cropping systems.

We developed activities and products in collaboration with Native gardeners/farmers that were culturally relevant materials for sharing agro-ecological knowledge, including materials about the importance of soil health, soil fertility, crop rotation, and how 3SI could play a key role in keeping soil healthy and in creating sustainable cropping systems in Native communities. During our first advisory board meeting and through the ethnographic interviews, we gathered data about the successes and barriers gardeners face in growing 3SI and the perceived needs growers have related to improving their practices. At our fall harvest advisory board meeting in 2022, we encouraged participants to reflect on the process of soil health testing and discuss plans for the future.

Objective Three: To determine the effects of 3SI crop yield, growth, and soil health.

Drs. McDaniel and Nair co-led this objective. Drs. McDaniel and Nair set a replicated randomized complete block design with each block replicated four times at the Horticulture Research Station in Ames, Iowa. Treatments included monoculture sweet corn, monoculture common beans, monoculture squash, and intercropping of sweet corn/common beans/squash. Monoculture plots were 9 m (30’) x 9 m, whereas the intercrop plots were 12 m (40’) x 9 m. Our advisory board of native community members suggested the varieties used at the ISU 3SI plot. Data was collected on stand establishment, weed population, weed suppression, crop growth [flowering, plant height, indirect measurement of chlorophyll (SPAD readings), and plant biomass], yield, and quality. We allowed more flexibility with our collaborator farms/gardens and gave them the option of fitting this experimental design into their existing practices, including size, number of replicates, and varieties used by their communities.

Dr. McDaniel led the soil health initiative and measured how 3SI affected soil health at the ISU plot and several small farms run by Native American communities. We used a combination of traditional soil health measurements and a novel, inexpensive, yet scientifically robust soil health indicator that engaged Native communities in citizen science. Combining these two approaches helped us determine the effect of intercropping on soil health. Furthermore, by engaging Native communities in setting up on-farm trials and soil data collection, we hoped to encourage and engage cultural links to traditional agriculture practices and promote sustainability.

For a visual guide to the ISU plots and planting procedures, see the files below:

For the 2020 field season:

Objective One: Assess the cultural, nutritional, and agricultural importance of Three Sisters Intercropping (3SI) among 5 Native American communities.

We conducted 12 interviews with Native growers in participating communities over video chat in the summer of 2020. Preliminary analysis of these interviews revealed multiple insights into the cultural, nutritional, and agricultural importance of Three Sisters agriculture to each community. Team member Kapayou pilot-tested the Nutrition Environment measures survey for applicability to the Native American setting and ease of use by non-nutrition specialists to begin the nutritional assessment. Below is the question set used by Christina Gish Hill over the course of her ethnographic interviews:

Cultural and Agricultural Importance of Three Sisters Intercropping Question Set:

- Why do you garden? How does it make you feel?

- Why do you grow foods of cultural importance to your nation? Why are these plants/foods important to you?

- What is the cultural and historical value of 3SI agriculture to your nation?

- What would you say is the social value of gardening? How does it bring people together?

- How often or how much space do you devote to Three Sisters? What affects your decision to grow corn, beans, or squash and to intercrop and to use specific techniques?

- What does it mean to have a respectful relationship with plants and soil? How do you enact that relationship? How much space do you farm? What foods?

- How did you gain your knowledge about gardening? How do you acquire new knowledge? What would you like to share about what you have learned?

- What kinds of barriers are you experiencing?

- How do you define food sovereignty? How do you feel about food sovereignty?

- How is your nation working towards food sovereignty?

- What barriers to food sovereignty do you experience?

- What are your goals for food sovereignty or food security in your community? What are your hopes and dreams?

- How often are 3SI foods eaten? Are they available in the surrounding region markets?

- What cultural or social significance are people aware of regarding maize, beans, and squash?

- Are there other people in your community we might interview?

Objective Two: Engage Native gardeners/farmers through citizen science

We designed a plot layout guide to be used by the ISU team and the collaborator Native communities. This guide described in detail how one could lay out a (3-SIP) research block in their community. We made several versions of this plot layout guide, which had to be tailored to collaborator gardener specifications in some instances. We also compiled a seed placement and time-to-plant guide. This guide included detailed schemas and measurements for gardens incorporating garden mounds. We wrote a soil sampling guide for collaborator gardener use. We collected soil samples from our participating Native gardeners and returned the testing results to them, explaining the results, answering questions, and making suggestions for soil amendments when asked. We hoped to collect a second round of soil samples at the end of the season, but all three of our farmers struggled to keep their plots going for various reasons, all Covid related. We hope for a better growing season to attain data. We also began working on a “Soil Health Kit Manual” to be used by our collaborating Native gardeners. This manual was launched during the 2021 field season.

Objective Three: To determine the effects of 3SI crop yield, growth, and soil health.

2020 was a difficult growing season both for Native growers and for the ISU research plots. Covid delayed the planting, so we were late putting seeds in the ground. We also suffered a massive derecho that destroyed most of the plants in our plots. Despite these challenges, we collected soil samples and as much plant and yield data as possible. We conducted a statistical analysis of data collected from the (3-SIP) garden maintained by ISU. We compiled this data into a comprehensive package that was used in discussions with various collaborators and within the ISU team. We also secured permission from our collaborating Native gardeners to conduct DNA analysis on our (3-SIP) garden soils and communicated with our UW-Madison collaborator about this analysis. We conducted the analysis in 2021.

For the 2021 field season:

Objective One: Assess the cultural, nutritional, and agricultural importance of Three Sisters Intercropping (3SI) among 5 Native American communities.

We completed two field seasons of ethnographic research to assess the significance of the 3SI to Native communities in the Midwest. Through participant observation and formal interviews, our team gained insight into current revitalization activities centered on food sovereignty. Conversations with gardeners revealed the significance of the three sisters for Native culture, food, nutritional security (community health?), and greater tribal sovereignty. A total of 14 interviews were conducted as of January 2022. As part of her extension work, Emma Herrighty joined Christina Gish Hill in her ethnographic interviews for this field season and asked her own set of questions in addition to Hill's set of questions that were outlined in the 2020 field season section. Herrighty's additional question set is listed below.

Seed Saving/Rematriation ethnographic question set:

- How did you get into seed saving?

- Who or where did you learn from?

- Why do you feel this work is important?

- What methods of seed saving and storage do you use?

- Are there any stories in your nation that highlight the cultural or historic importance of seeds, if you feel comfortable sharing?

- Are there any specific varieties associated with those stories?

- Can you say a little about seed sovereignty? What does it mean to you?

- How does this relate to other aspects of Native sovereignty?

- What does the term “rematriation” mean to you?

- How do you use this word?

- Why do you think it’s important that we use this word as opposed to others?

- Why are you involved in this process? What does it entail?

- Why do you think this movement is important for Native communities?

- What do you envision as the future of seed saving and rematriation?

Preliminary conversations and discussions with Native collaborators on community needs related to nutritional environment continued in the last grant year (Sept 2020- 2021) but were hampered by the COVID-19 pandemic and travel restrictions. Questions and themes were developed and shared in the 2022 advisory board meeting.

Objective Two: Engage Native gardeners/farmers through citizen science

Based on our stakeholders’ needs assessment and feedback, our team organized two Virtual Workshops (August 7th and October 30th, 2020) and a stakeholders meeting (February 18th, 2021) to disseminate our research findings. The workshops catered to native gardeners and community leaders in the Native American communities in Iowa, Nebraska, Minnesota, and Wisconsin. The virtual workshops covered the following topics:

- Soil fertility and health in home gardens

- How to set up drip irrigation

- Seed saving for home gardeners

- DIY Soil Health Tests

- Key insect pests of squash, beans, and corn

- Basics and troubleshooting of composting

Both workshops had 15-20 participants and had an engaging Q&A session. Below are the learning and action outcomes from our workshops:

- Participants learned about several IPM tools and techniques.

- They gained specific and detailed information on soil health indicators and DIY soil health kits.

- Participants received information on creating high-value and quality compost in their backyards and learned several troubleshooting methods for proper composting.

- In addition to participants engaging with subject matter specialists, both workshops created a platform for peer-to-peer learning.

On July 22nd, 2021, we also held an ISU Horticulture Farm Field Day in person, highlighting the Three Sisters plots at ISU. There were around 160 people in attendance. Participants were able to observe the study in person and engaged in discussions and feedback.

Our team also organized two on-site in-person workshops (Green Bay, WI and Niobrara, NE). The workshops covered the following topics:

- Demonstration of soil health kit

- Insect management in vegetable crops

- Cover crops to improve soil organic matter

- Demonstration of how to make compost

Objective Three: To determine the effects of 3SI crop yield, growth, and soil health.

This project had a very successful 2021 growing season. Our experiment furthered our understanding of the impact of the 3SI on plant health and yield. Despite some setbacks to our growing season, all crops produced well, and we gathered some promising statistics. We were able to mitigate the corn smut issue to a degree by removing immature smut galls by hand. Removing the smut galls also allowed us to collect an additional yield component since smut is edible and considered a delicacy in some cultures.

This season did introduce a new disease issue; bacterial spot of cucurbits (Xanthomonas cucurbitae). This disease can be devastating to fruit yields. We lost approximately 40% of the crop (across treatments) before harvest. However, the nature of the disease is that it makes fruit more vulnerable to colonization by secondary fungi and bacteria, increasing the decomposition rate in post-harvest storage. Due to this, we lost the majority of our marketable yield in the weeks following harvest.

Soil samples were taken from the Three Sisters research garden maintained at the NICC campus so the research team could communicate soil-nutrient deficiencies to the staff at NICC to help them progress in the project. On October 9th, a research team member traveled to Stoughton, Wisconsin, to extract soil samples from a Three Sisters research garden maintained by a core collaborator and member of the Oneida Nation, Daniel Cornelius. These soil samples were used to compare how the Three Sisters intercropping system affects the soil compared to monocrop plots. Samples were collected at the ISU plots after harvest and processed for microbial biomass, water holding capacity, gravimetric water content, Nitrogen testing, potential mineralizable nitrogen and carbon, and particulate organic matter. In addition, parallel DIY health tests were also conducted.

For the 2022 Field season:

Objective One: Assess the cultural, nutritional, and agricultural importance of Three Sisters Intercropping (3SI) among 5 Native American communities.

Under the ethnography portion of objective one, led by Dr. Gish Hill, we conducted ethnographic research in 2022 in all five communities and conducted six in-person interviews. Dr. Gish Hill traveled with graduate students Emma Herrighty and Susana Cabrera to each community, recruiting participants and learning about gardening and food sovereignty programs. She connected with growers who had plots last year, encouraging them to grow again this year. We had four Native growers who grew plots in the summer of 2022. She continued to build rapport by spending time in communities, helping to weed and harvest, cooking together, and taking baseline soil samples for potential participants. We are in the process of transcribing the remaining recordings.

Under the nutrition portion of objective one, led by Dr. Donna Winham, we created two nutrition environment measures for this project: the nutritional store assessment data and the nutritional store assessment tool redesigned for grocery stores on or near reservations. Dr. Winham also recruited a student to work on the project, to travel to communities, conduct interviews about access to food and diet, and assess the nutrition environment in and around each Native community. The student worked with the team to assess the nutrition environment in 11 grocery stores near two of the collaborating Nations.

The store assessments involved utilizing the already established Nutrition Environment Measures Survey for Stores (NEMS-S) and creating a new NEMS-S document focused on Native American foods. Both tools were used to assess the presence and accessibility of various food items that were deemed healthy, their regular alternatives, and traditional (for the newly created Native American instrument). For this project, “accessibility” referred to the quality and price of the items and the distance to the store.

Short interviews were also conducted at stores with managers and employees who agreed to participate. The interview questions primarily focused on where stores get their food from, whether they carry any locally produced food items, whether they have Native American customers shop in their store, and what their customers may purchase. The stores that were chosen for assessment were limited to a certain radius, with the belief that community members are more likely to frequent closer stores. Some members of the advisory board also mentioned specific stores that may have fallen outside this radius; these were included in the assessment. An additional advisory board meeting was held this past fall after the harvest to share the final results with members and discuss where we will go from here with the information the project has gathered.

Objective Two: Engage Native gardeners/farmers through citizen science

Dr. Nair led the ISU Horticulture Farm Plots and Extension objectives. The field season officially kicked off in May with tilling and raised-bed (mound) construction on our ISU research plot. Using the protocol developed by the advisory board, the team established the study on a certified organic field at the ISU Hort Research Station. The field was prepared by reconstructing the mounds and establishing the four treatments (corn monocrop, squash monocrop, bean monocrop, and corn-squash-bean intercrop. Treatments were randomized, and each treatment in each replication consisted of a 20 x 20ft plot. Each plot comprised 16 mounds. The garden was expanded to include space for rematriated seeds due to the pathogens and pests from previous years.

The corn, bean, and squash varieties in the research garden for the 2022 growing season were the Winnebago Spotted, Scarlet Runner, and Warren Turban, respectively. In the rematriation space, we had the Algonquin Long Pie, Wampum bean, and an unnamed landrace bean retrieved from the UDSA plant introduction station and identified by Native collaborators as needing rematriation. Baseline soil samples were taken before planting and again at the end of the season.

During the spring of 2022, we held several zoom meetings with each community to determine which types of workshops were most needed in that particular community. We traveled to the Nebraska communities in June and July to conduct workshops. The workshops catered to native gardeners and community leaders in the Native American communities in Iowa, Nebraska, Minnesota, and Wisconsin.

This past reporting year, we have held five collaborative workshops with our partners in Macy, NE, and Santee, NE. This process began during our advisory board meeting, where our collaborators were able to request topics and ideas. We followed up with each community and planned workshops based on community interests and need. The workshop topics for the 2022 year have been about understanding soil and garden health. The first workshop occurred at the Umhomon Public School gardens in Macy, NE. We presented on soil and plant health and had age-appropriate demonstrations on agriculture systems. Additionally, one of our collaborators in Oneida invited us to present to the local 4-H club about garden planning, how to plant a garden, and soil amendments. We worked with the youth to plant a 4-H garden during this visit. After the harvest, we conducted a final workshop with the Santee on soil health. We completed several educational activities during the fall. We visited our Oneida collaborators twice to assist with the harvest, and Christina Hill visited both the twin cities and our Omaha collaborators in Sioux City to help with seed saving and seed keeping.

This past year we have also been invited to present and develop workshops for various non-Native communities. In the spring of 2022, we presented to the second-grade class in a Des Moines Public School elementary school and set up two stations for students to rotate through. These visits incorporated a history and anthropological understanding of the Three Sisters and an agronomical and soil perspective on the three plant dynamic. We also helped this school start a small Three Sisters garden. We also held field trip for this class in the fall to visit the Three Sisters Plots at the ISU Horticulture Research Station, providing them with a tour of the Station and the plots, as well as activities around soil health.

Lastly, the project was contacted by two professors at Iowa State in the Department of Agronomy, who were teaching a domestic travel course on plains agricultural systems. They requested permission to tour our research garden at the Horticultural Research Station, and Dr. Christina Gish Hill led a multifaceted discussion on the relationships between Native peoples, agriculture, and the land.

Objective Three: Evaluate the effects of 3SI on crop yield and soil health

The 2021 growing season showed a lower average yield with the 3 Sisters. However, LER was around 2, which is considered high since the range is usually 1.22-1.3. We can interpret this as 3SI being more productive with less land but with intense limitations, including smut, bacteria pathogens, and variable environmental conditions.

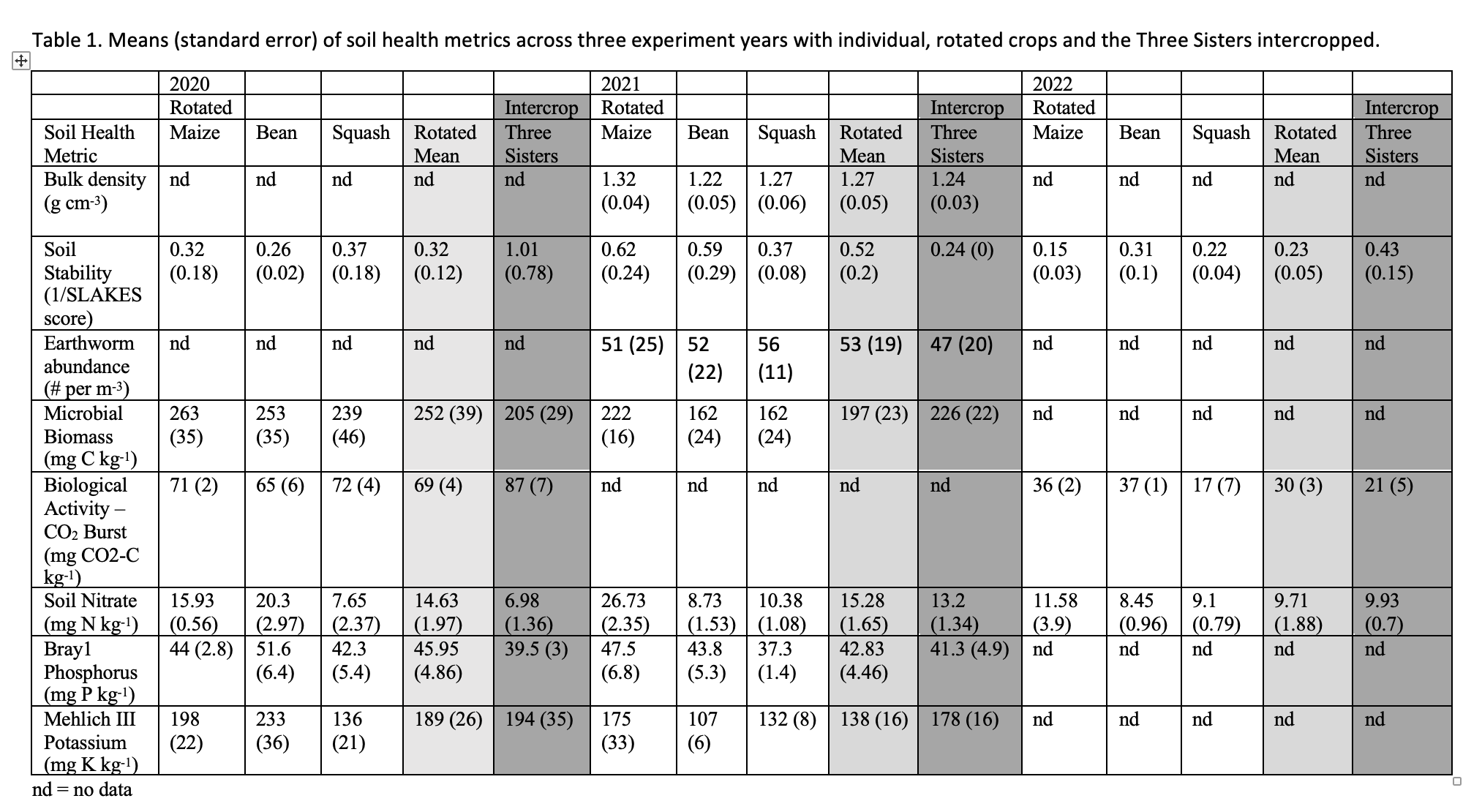

The soil health objective was led by Dr. McDaniel. To determine if planting the Three Sisters (maize, beans, and squash) together resulted in increased soil health, we measured several physical, biological, and chemical indicators of soil health in the Three Sisters Garden and compared them to the monocrop soil. We measured these chemical indicators over three growing seasons at a randomized, complete block design experiment near Ames, Iowa, USA. At the end of the growing season, we sampled and determined salt-extractable Nitrate and found that intercropping the Three Sisters had consistent effects on soil nitrate, decreasing it relative to sole cropping and increasing biological activity (as assessed by CO2 Burst). Soil respiration was consistently marginally higher in the 3SI treatment, approximately 6%, even though the decomposition rates were lower in the 3SI. Other effects were inconsistent, i.e. only occurred in one year, and may be explained by either the varieties used for the year or weather conditions. It is clear that intercropping with maize, beans and squash altered soil biology and fertility. Future research should explore using stable isotope tracers to study flow of nutrients between the intercropped sisters and soil. See the charts in the Research Conclusion section for more specific data results.

Objective One: Assess the cultural, nutritional, and agricultural importance of Three Sisters Intercropping (3SI) among 5 Native American communities.

Ethnography Portion:

Under the ethnography portion of objective one, led by Dr. Gish Hill, we conducted ethnographic research in 2022 in all five communities and conducted many in-person interviews. Dr. Gish Hill traveled with graduate student Susana Cabrera and Agricultural Specialist Valeria Cano Camacho to each community, recruiting participants and learning about gardening and food sovereignty programs in each community. She connected with growers who had plots last year, encouraging them to grow again this year. We had four Native growers who grew plots in the summer of 2022. Gish Hill continued to build rapport through spending time in communities, helping to weed and harvest, cooking together, and taking baseline soil samples for potential participants. By December 2022, we had conducted six interviews, and are currently transcribing the remaining recordings. These recordings will be incredibly useful to those seeking to understand the importance of the Three Sisters for Native gardeners and Native Communities. They will assist in the preservation and dissemination of invaluable cultural knowledge. What is more, the relationships we have cultivated through our ethnographic research will continue to present opportunities for further research and community building beyond this project's scope.

In regard to the results of this ethnographic research, we found that the Three Sisters and seed rematriation is vital to the food ways and cultural integrity of native peoples. The specifics of each gardeners' experience are nuanced will be expanded upon in multiple publications that are currently under development

Nutrition Portion:

The mean NEMS-S store assessment for the 10 stores was 27.5 (± 4.3), with a range of 22-34 out of a possible 54 points. All stores had the availability of 6 of the 11 measures (lower fat milk, fresh fruits, fresh vegetables, diet soda and 100% juice, whole grain bread, and healthier cereals). Few stores had the 3 measures of lean ground meat, lower fat hot dogs, or lower fat frozen dinners. Most stores had baked chips and lower-fat baked goods available. The NEMS-S scores, food availability, and price comparisons were not significantly different between the 8 regular markets and the 2 Walmart stores.

The presence of the Three Sisters crops (beans, corn, squash), wild rice, cornmeal, and maple syrup was noted. These historical or traditional foods were mentioned as culturally important by the Advisory Board members and in the ethnographic interviews. With the exception of one store, at least one variety of dry beans was available. All stores carried an assortment of plain canned beans and baked beans. Fresh ears of corn were available, although heirloom types were not present. Only four stores stocked fresh squash (butternut and acorn). Eight stores stocked corn meal, six carried wild rice, but only four had real maple syrup available.

Despite the proximity of the retail markets surveyed, few historic or traditional foods were available. The updated Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations (FDPIR) food packages contain more culturally appropriate foods such as bison, wild rice, walleye, and corn meal. It is possible that Native clientele are not looking for indigenous foods at the markets included in this study. Food preferences and shopping patterns of the Native populations in the store service areas are unknown.

The information gathered from the store assessments can inform those in the Native American communities of food options available to improve their nutrition. In addition, due to the limited radius of stores that were assessed, this information can be presented to and used by the communities to shop more locally, thus potentially influencing the local economy. Many of the store staff interviewed indicated that they do not carry much local food, if any, and even fewer carry any product produced by the Native American communities. However, many indicated they would like to carry more locally produced items, including those produced by the Native American communities. An increase in locally or Native American-produced items in stores would potentially improve the rural communities' economy.

Objective Two: Engage Native gardeners/farmers through citizen science

This project thoroughly accomplished the goal of promoting citizen science, relationship building, and having an extension presence in the Native American and surrounding communities. Throughout the project, we have reached our target audience of Native American gardeners and farmers on the Omaha, Santee Sioux, Oneida, and Menominee reservations and Native gardeners in Sioux City and Minneapolis/ St. Paul through outreach into their communities, attendance at an advisory board meeting held at Iowa State University, virtual workshops, and by distributing extension materials and videos. The workshops and field days we conducted shared information with Native growers and local growers about organic horticulture, soil health, and Three Sisters agriculture. Two of our graduate students were especially vital in expanding our outreach scope. As part of his extension work, Derrick Kapayou took soil samples of potential participants' gardens, providing information about growing techniques specific to each garden during our ethnographic visits, and taught Native farmers and gardeners to read the soil test results for their gardens once they were processed. Extension work conducted by Emma Herrighty involved learning about the protocols for saving seeds and then working with Native collaborators to rematriate the seed grown at ISU to Native growers. In addition to the rematriated seeds, we returned information about the seed and how it was handled. We have also built networks --using social media, specifically Facebook--between Native gardeners within their home communities and across tribal nations to share knowledge and resources, like seeds. These networks will continue to grow beyond the bounds of this project, and Native growers will continue to reap the benefits of this disseminated knowledge.

Objective Three: Evaluate the effects of 3SI on crop yield and soil health

Crop Yield:

The 2021 growing season showed a lower average yield with the 3 Sisters. However, LER was around 2, which is considered high since the range is usually 1.22-1.3. We can interpret this as 3SI being more productive with less land but with intense limitations, including smut, bacteria pathogens, and variable environmental conditions.

Soil Health

The soil health objective was led by Dr. McDaniel. To determine if planting the Three Sisters (maize, beans, and squash) together resulted in increased soil health, we measured several physical, biological, and chemical indicators of soil health in the Three Sisters Garden and compared them to the monocrop soil. We measured these chemical indicators over three growing seasons at a randomized, complete block design experiment near Ames, Iowa, USA. At the end of the growing season, we sampled and determined salt-extractable Nitrate and found that intercropping the Three Sisters had consistent effects on soil nitrate, decreasing it relative to sole cropping and increasing biological activity (as assessed by CO2 Burst). Soil respiration was consistently marginally higher in the 3SI treatment, approximately 6%, even though the decomposition rates were lower in the 3SI. Other effects were inconsistent, i.e. only occurred in one year, and may be explained by either the varieties used for the year or weather conditions. It is clear that intercropping with maize, beans and squash altered soil biology and fertility. Future research should explore using stable isotope tracers to study flow of nutrients between the intercropped sisters and soil. See the charts below for more specific data results.

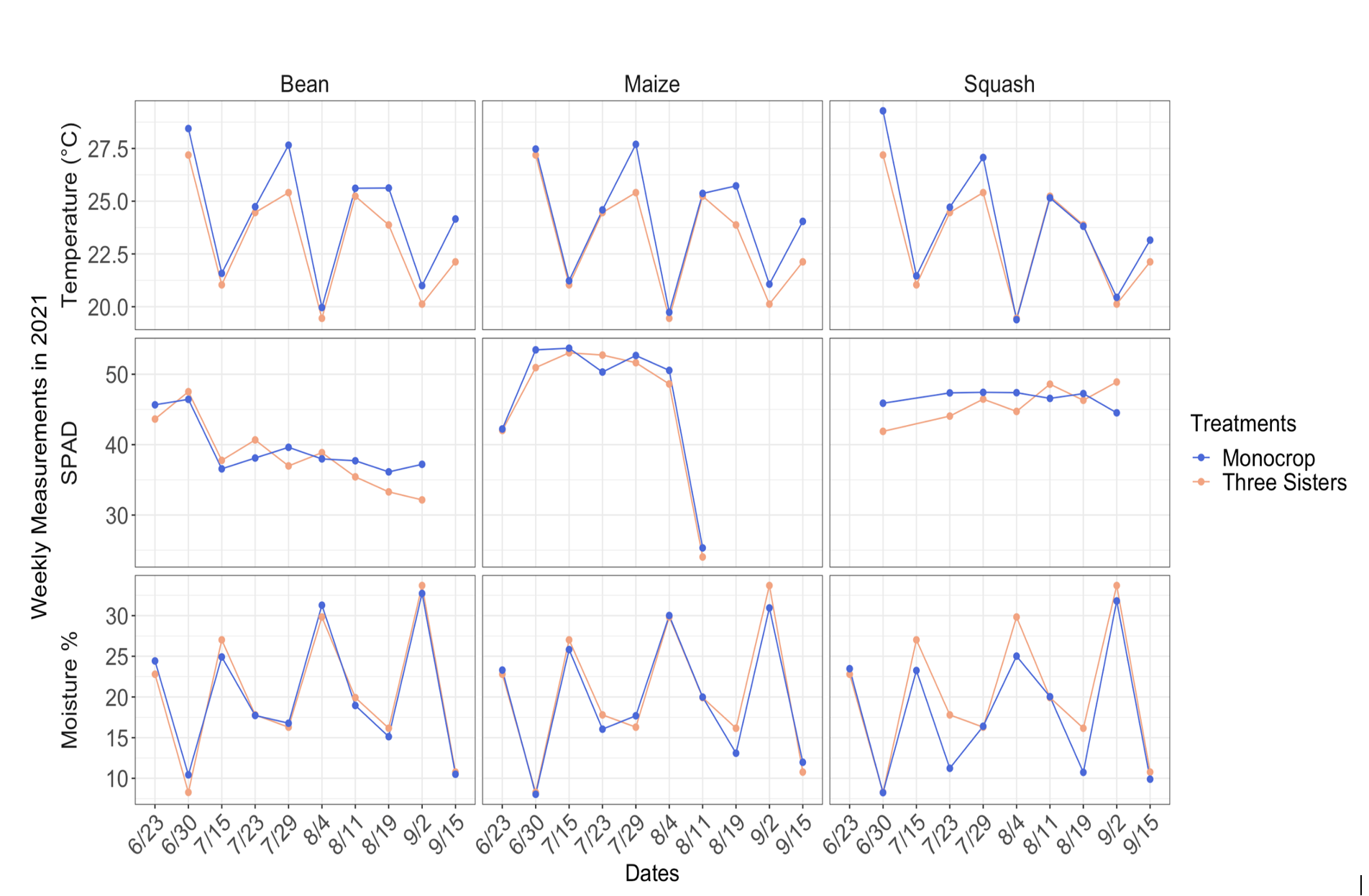

For the 2021 growing season, soil temperature, moisture and SPAD (chlorophyll proxy) were measured on a weekly basis. The blue line is the average of the monocrop treatment, and the salmon color is the Three Sisters treatment. One-way ANOVAs showed a moderate significant effect (p – value = <.01) between treatments over the whole growing season for soil temperature and moisture, but not SPAD (p-value = 0.67).

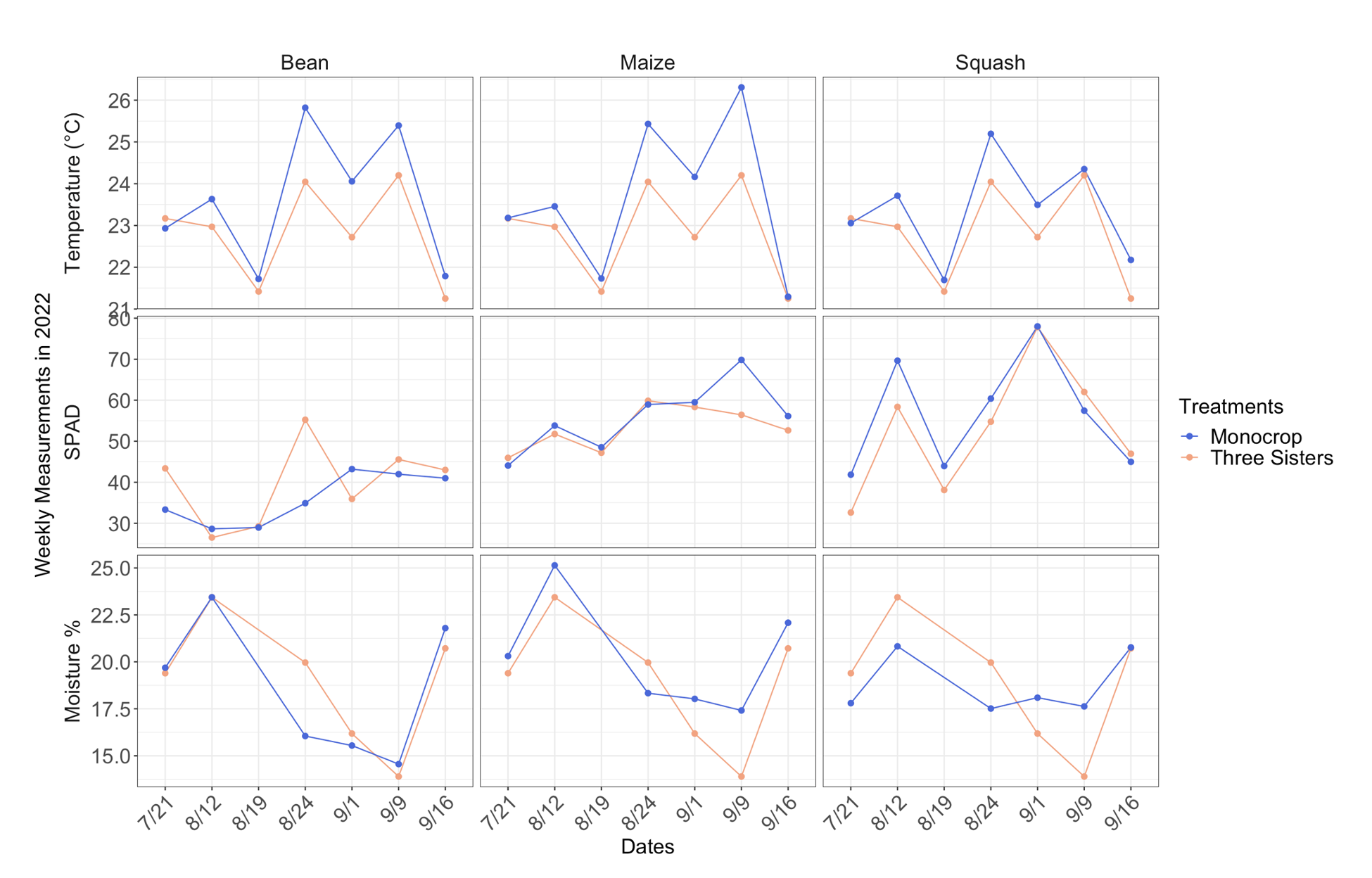

For the 2022 growing season, soil temperature, moisture and SPAD (chlorophyll proxy) were measured on a weekly basis. The blue line is the average of the monocrop treatment, and the salmon color is the Three Sisters treatment. One-way ANOVAs showed a significant effect (p – value = <.0001) between treatments over the whole growing season for soil temperature but not for soil moisture and SPAD (p-value = 0.64 & 0.53, respectively).

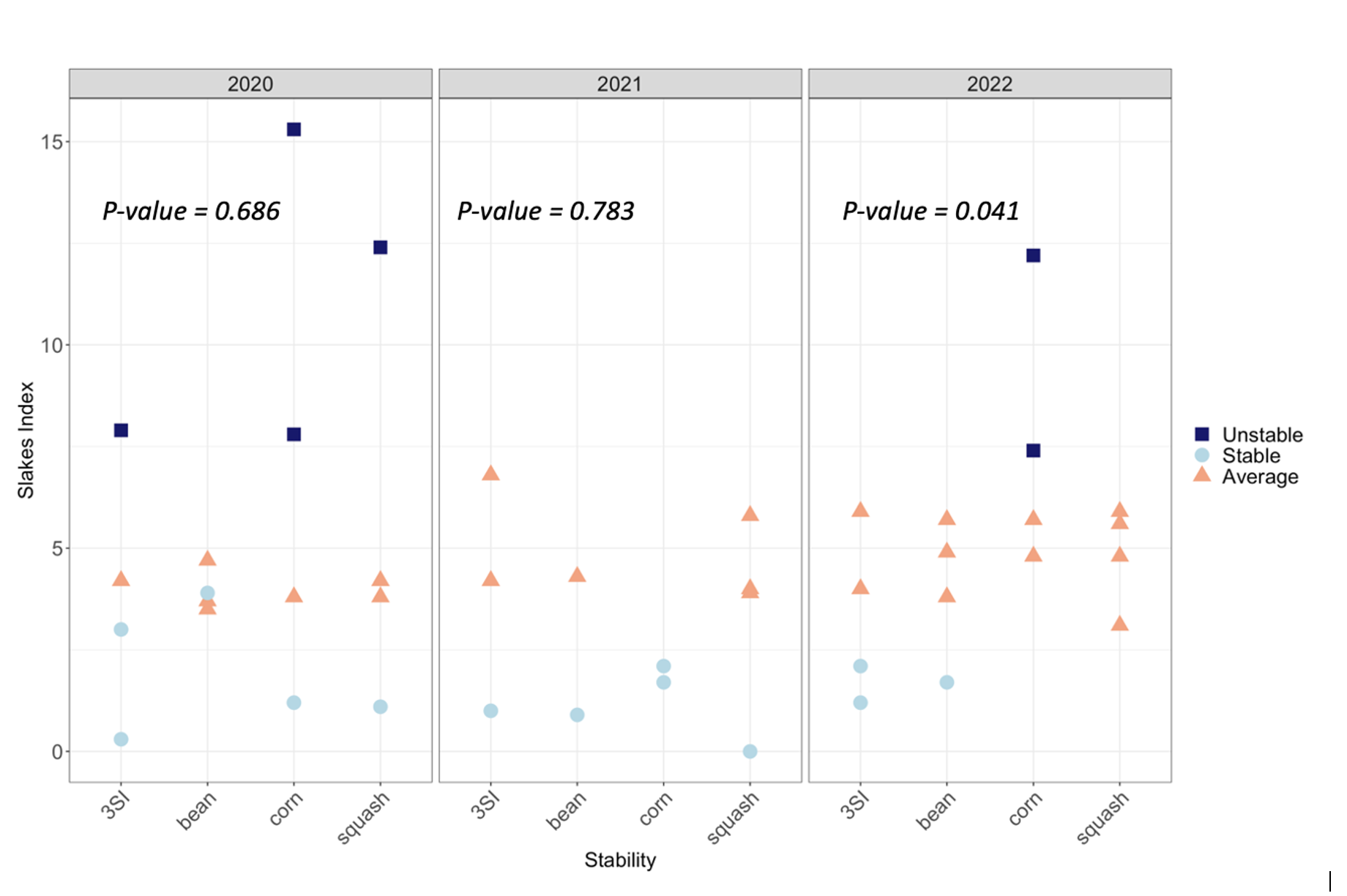

A one-way ANOVA for each year showed a non-significant effect with crop treatments for 2020 and 2021 growing season. However, a significant effect (p value = 0.041) for the 2022 growing season. The most unstable plots were from the corn monocrop treatment, and the 3SI treatment had the most stable plots in that season.

Education

Overview

Our educational approach was fully collaborative, and we worked with the Native growers on the project to develop various interactive activities, including research procedures, workshop topics, and educational materials. Our main source of brainstorming was advisory board meetings, but we also contacted partners and stakeholders to obtain workshop and educational event suggestions. Each year’s workshop topics were based on the previous year’s requests from the advisory board and individual communities.

The results of our study were disseminated back to our community collaborators in multiple ways. One of our most active forms of communication was our Three Sisters Gardening Project Facebook group, managed by Christina Gish Hill. We provided weekly updates on the occurrences of the research and rematriation garden, as well as travel updates and workshop promotions. On a more formal platform, we hosted the Three Sisters Project webpage with an official Iowa State University domain. Here we updated our team members and blog about events related to the project. This webpage is also the home to the education videos related to the DIY Soil Health Kit.

We communicated often with our interviewees and sent them transcripts of their interviews for feedback. We sent emails with garden assessment results and soil test results and made phone calls to explain the results of those tests. Finally, results from the nutrition assessments were disseminated to the communities of interest as an infographic summarizing what healthy foods and traditional foods are available to them. Information regarding individual stores remained confidential, but communities were provided information on items available and the average price in a given radius.

Advisory Board Meetings

Because of the pandemic, our team had to curtail many of the proposed activities for 2020, such as on-farm demonstration trials, in-person trainings, community visits, and focus group meetings. Our team hosted an Advisory panel meeting in February 2020 that facilitated discussions about our research plots at the Horticulture Research Station, extension and outreach activities, and overall project implementation in collaboration with regional partners. We were required to host our 2021 advisory panel meeting virtually as well, but advisors from each community attended, and we facilitated engaging discussions on how to move the project forward regarding the research plots at ISU as well as extension and outreach activities.

The 2022 Advisory Board meeting was held on March 11th and 12th in Ames, IA. In total, there were 15-20 total attendees. It was a hybrid event, and participating members traveled from Santee, NE; Macy, NE; Winnebago, NE; and Oneida, WI. Board members also joined via Zoom from Minneapolis, MN. On the first day, we toured the Horticultural greenhouses and invited a local celebrity chef from Santee, NE, to cook some of the meals with traditional ingredients and foods. The following day started with a project update from the Iowa State team and a discussion that responded to those updates and outlined the board members’ expectations for the rest of the project. This discussion covered every sub-discipline of the project. The advisory board members were then given a tour of the Ames Plant Introduction Station and Horticultural Research Station. Our final session included dinner and a trade event in which everyone participated.

We held a final Advisory meeting from November 11th - 13th, 2022, to update our members about the 2022 harvest results and brainstorm how to move forward with the information and tools the Three Sisters Project has gathered in its three years. This event also included community-building exercises, a campus greenhouse and McDaniel lab tour, and networking and seed-sharing sessions.

Workshopping 2020

In the first year (2020), our team pivoted to an online mode of outreach, utilizing Zoom and WebEx to share culturally relevant agroecological knowledge. This knowledge included the importance of soil health, soil fertility, crop rotation, and how 3SI could play a key role in keeping soil healthy and creating sustainable cropping systems in Native communities. Based on the needs assessment, our team organized two Virtual Workshops (7 August and 30 October 2020) to cater to native gardeners and community leaders in the Native American communities in Iowa, Nebraska, Minnesota, and Wisconsin. The virtual workshops covered the following topics:

- Soil fertility and health in home gardens

- How to set up drip irrigation

- Seed saving for home gardeners

- DIY Soil Health Tests

- Key insect pests of squash, beans, and corn

- Basics and troubleshooting of composting

Both workshops had 15-25 participants and had an engaging Q&A session. Participants learned about several IPM tools and techniques and gained specific and detailed information on soil health indicators and DIY soil health kits. Participants also received information on how to create high-value and quality compost in their backyards and learned several troubleshooting methods for proper composting. Finally, in addition to participants engaging with subject matter specialists, both workshops created a platform for peer-to-peer learning.

Workshopping 2021

Because we were finally able to travel in 2021, our team organized two on-site, in-person workshops (Green Bay, WI and Niobrara, NE). The workshops covered the following topics:

- Demonstration of how to use soil health kit

- Insect management in vegetable crops Cover

- Which crops can improve soil organic matter

- Demonstration of how to make compost

Each workshop again had 15-25 participants. Because we were in person, attendees were able to actively participate. The workshops were held at a satellite garden in each community. The participants used the soil health kit to assess the satellite plot. They also worked with our team to build their own compost pile. The topics also lead to engaging Q&A sessions. Throughout the workshops, our team gathered valuable insights into the gardening practices of both communities. We also received excellent feedback from our workshops, which helped us develop materials and educational tools for our 2022 virtual and in-person workshops and community engagement events.

Workshopping 2022

Over the course of 2022, we held six collaborative, in-person workshops, all of which involved understanding soil and garden health and seed saving. The first four were with our partners in Macy, NE, and Santee, NE.

The first workshop occurred at the Umhomon Public School gardens in Macy, NE. We presented on soil and plant health and had age-appropriate demonstrations on agriculture systems. The students created an agriculture color bracelet to help them understand the different concepts of agricultural systems. The second workshop was for adult community members. Activities were related to making their own potting mix and understanding the purpose of each ingredient. Participants then potted their seedlings, which they could later transfer to their home gardens.

The third workshop focused on water usage in gardens and building a rainwater catchment system from materials found in local garden stores. The fourth workshop included installing a tumbler composting system and understanding the necessary ingredients. The presentation was also set up as conversation and discussion since the additional permaculture and seed-saving topics were already well understood. The fifth workshop took place in the twin cities and covered seed finding and keeping. The sixth and final workshop was in Sioux City with our Santee collaborators and covered soil health. These workshops also include a brief crop scouting assessment of the local gardens and collecting soil samples. To recap, the 2022 workshops covered the following:

- Soil and plant health for K-12 students

- Intro to soil and garden health

- Rainwater catchment systems

- Composting and intro to permaculture

- Seed Finding and Keeping

Additional Workshops and Activities

Throughout 2022 we were invited to present and develop workshops for various non-Native communities. We presented to the second-grade class in a Des Moines Public School elementary school and set up two activity stations for students to rotate through. These activities helped them understand the historical and anthropological aspects of the Three Sisters, as well as the benefits the sisters bring to the soil. We also helped the school start a small Three Sisters garden.

Additionally, one of our collaborators in Oneida invited us to present to the local 4-H club about garden planning, how to plant a garden, and soil amendments. We worked with the youth to plant a 4-H garden during this visit.

Lastly, the project was contacted by two professors at Iowa State in the Department of Agronomy who were teaching a domestic travel course on plains agricultural systems. They requested permission to tour our research garden at the Horticultural Research Station, and afterward, Dr. Christina Gish Hill led a multifaceted discussion with the students about the relationships between Native peoples, agriculture, and the land.

Project Activities

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation Summary:

Throughout the project, we have reached our target audience of Native American gardeners and farmers on the Omaha, Santee Sioux, Oneida, and Menominee reservations and Native gardeners in Sioux City and Minneapolis/ St. Paul through outreach into their communities, attendance at an advisory board meeting held at Iowa State University, virtual workshops, and by distributing extension materials and videos. The workshops and field days we conducted shared information with Native growers and local growers about organic horticulture, soil health, and Three Sisters agriculture. As part of his extension work, Derrick Kapayou took soil samples of potential participants' gardens, providing information about growing techniques specific to each garden during our ethnographic visits, and taught Native farmers and gardeners to read the soil test results for their gardens once they were processed. Extension work conducted by Emma Herrighty involved learning about the protocols for saving seeds and then working with Native collaborators to rematriate the seed grown at ISU to Native growers. In addition to the rematriated seeds, we returned information about the seed and how it was handled. We have also built networks --using social media, specifically Facebook--between Native gardeners within their home communities and across tribal nations to share knowledge and resources, like seeds.

We have also reached graduate and undergraduate students at Iowa State who have attended advisory board meetings, worked in our Three Sisters garden plots, and helped with lab research. During the 2022 growing season, the project took on four undergraduate students from Iowa State University. These students were trained in Indigenous seed varieties and appropriate seed preservation and care methodologies. Some examples include creating mounds for planting, direct-seeding Three Sisters intercropped system, transplanting corn from greenhouse seedlings, developing a pollination garden plan, and hand-pollinating corn and squash plants. The students were also trained in plant and soil health data collection protocols, such as SPAD, soil temperature and moisture, and sampling. Students also received experience in crop scouting for smut and squash bore. Lastly, students had the opportunity to answer questions about their experiences.

Additionally, the project hosted an intern from the Iowa State University George Washington Carver Internship Program. This second-year student from Kirkland Community College worked in the McDaniel Lab and Three Sisters project for eight weeks. He collected the weekly SPAD, soil temperature, and moisture data, then processed and graphed his findings. However, due to the length of the internship, his final 5-minute oral presentation and poster discussed only the 2021 growing season data. He presented his work "Three Sisters Intercropping (Maize, Beans, and Squash) effect on Soil Microclimate and Plant Health '' to the GWC Internship Program and guests. During his time with the project, he learned some R programming data visualization language, advanced excel functions, and experience doing public speaking and answering questions.

Another graduate student was trained on the original NEMS-S and developed a modified Native American NEMS-S instrument. Based on previous research, interview questions were developed, and data was collected from store managers. The graduate student also gained professional development experience through training other staff members to use the instrument.

We reached our target audience of sustainable agriculture researchers and practitioners by presenting a poster at MOSES (Midwest Organic and Sustainable Education Services Conference), a paper at the Indigenous Food Sovereignty Symposium at Northern Michigan University, and the NIFA CARE project director's meeting. In addition, students attended skill-building workshops and roundtable discussions, allowing them to network with folks in organic farming.

We have also reached our target audience of sustainable agriculture researchers and practitioners through six publications, three farm reports with Iowa State University extension, two Master's Theses, and a peer-reviewed article in Agriculture and Human Values. These publications have led to media interviews with Iowa Farmer Today, Midstory Podcast, Scientific American, and The West magazine.

We reached the gardening public in central Iowa with a Field Day at the ISU Horticulture Research Station, two presentations at Living History Farms, and a presentation to second graders at a Des Moines Public School. We reached a wider gardening public by presenting to the Penn State Master Gardeners. We reached a much wider audience via the publication of seven interviews for popular press articles. Many journalists reached out to our P.I., Christina Gish Hill, to learn about the project. These included journalists from the Midstory Podcast, The West, Ames Tribune, XRay 91.1, Wort 89.9, U.S.A. Today, and Scientific America. With the exception of the U.S.A. Today interview, which will be published this March, all interviews have been released to the public. This exposure has allowed us to spread knowledge of the cultural and agronomic importance of the Three Sisters and their contributions to sustainable, Native food systems.

This project has presented a plethora of career development and community-building opportunities. On March 3rd - 6th, graduate students and staff attended the 19th Annual Great Lakes Indigenous Farming Conference in Callaway, Minnesota. They had the opportunity to listen to Winona LaDuke, Elizabeth Hoover, and many other great professionals about food, energy, economics, and land sovereignty. In addition, they attended workshops related to Tibial Food, Agricultural Business, Indigenous Sciences, and Innovation. The attendees were able to network and meet folks from across the United States to discuss and explore new ideas and perspectives.

Christina Gish Hill attended the Food Sovereignty Symposium & Festival on May 20th at the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community and Northern Michigan University. The conference focused on creating spaces for presenters to share experiences and explorations related to food justice, Indigenous agriculture in North America, and Indigenous sovereignty. Ethnographic interviews and conversations have led PIs, students, and staff to be invited to community Pow Wows. This summer, we attended the Santee Sioux Nation Pow Wow on July 17th in Santee, Nebraska. We experienced the grand entrance of local community leaders and honorees and were able to appreciate cultural celebrations, which helped our students learn about culturally appropriate behavior and cultural diversity.

Supporting Materials

Learning Outcomes

- irrigation

- Composting

- Pest management

- Seed saving

- Soil health

Project Outcomes

Three sisters intercropping

Two Native farmers, one in Wisconsin and one in Nebraska, had not tried to grow three sisters intercropped before

Information Products

- Returning the ‘three sisters’ – corn, beans and squash – to Native American farms nourishes people, land and cultures (Article/Newsletter/Blog)

- CAN TRADITIONAL ECOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE BE INTEGRATED INTO MODERN CROPPING SYSTEMS TO ENHANCE SOIL AND WATER CONSERVATION? (Article/Newsletter/Blog)

- Reuniting the Three Sisters: collaborative science with Native growers to improve soil and community health (Article/Newsletter/Blog)

- Collaborative science with Native farmers can overcome barriers to Improve soil and community health (Conference/Presentation Material)

- Reuniting the Three Sisters: Using Indigenous Methodologies to Learn More About Three Sisters Intercropping (Webinar)

- Three Sisters Reunited: Gardening as Indigenous Resurgence (Conference/Presentation Material)

- Reuniting the Three Sisters: Native American Intercropping, Seed Saving, and Plant Health (Fact Sheet)

- Indigenous Foodways of the Midwest: The Impacts of Contact and the Importance of Revitalization (Conference/Presentation Material)

- Seed Sovereignty, Rematriation, and Three Sisters Intercropping in Native American Communities (Thesis)

- Indigenous Food Sovereignty in the American Corn Belt: Resurgence in the Face of Disruption (Conference Proceeding)

- Appropriation of Land and Seeds: Settler Colonialism's Impact on Native American Agriculturalists in the Midwestern U.S.” (Conference/Presentation Material)

- Seeing the Seeds Home: Increasing Opportunities and Responsibilities of Non-Native Seed-Holding Institutions within the Seed Rematriation Movement (Conference/Presentation Material)

- Reuniting the Three Sisters: Native American Intercropping and Plant Health (Conference/Presentation Material)

- Reuniting the three sisters: enhancing community and soil health in Native American communities (Conference/Presentation Material)

- Growing Together With the Three Sisters: Indigenous Gardening for Cultural Resurgence (Training Agenda)

- Three sisters offer lessons of sustainability today (Article/Newsletter/Blog)

- Three Sisters Gardening Project (Article/Newsletter/Blog)

- Three Sisters Project (Website)

- Native intercropping of 'three sisters' — corn, beans and squash — benefits land, ISU research shows (Article/Newsletter/Blog)

- Christina Gish Hill on the Three Sisters and Native Agriculture (Article/Newsletter/Blog)

- Recovering Indigenous Agriculture (Article/Newsletter/Blog)

- Native agriculture never went away. Now it is on the rise. (Article/Newsletter/Blog)

- Cultural connections to soil and agronomic impacts of the maize, bean, squash polyculture methods in 5 Indigenous Communities of the Upper US Midwest (Thesis)